The Story of a Cylindrical Phonograph by Thomas Edison

- Transfer

The phonograph was invented as a result of the work of Thomas Edison on two other inventions: telephone and telegraph. In 1877, Edison worked on a device that could record messages in the form of recesses on a paper tape, which could then be sent repeatedly by telegraph. The study led Edison to the idea that a telephone conversation could be recorded in this way. He experimented with a membrane equipped with a small press held above paraffin coated fast-moving paper. Vibrations created by voice left marks on paper.

The phonograph was invented as a result of the work of Thomas Edison on two other inventions: telephone and telegraph. In 1877, Edison worked on a device that could record messages in the form of recesses on a paper tape, which could then be sent repeatedly by telegraph. The study led Edison to the idea that a telephone conversation could be recorded in this way. He experimented with a membrane equipped with a small press held above paraffin coated fast-moving paper. Vibrations created by voice left marks on paper.Later, Edison replaced the paper with a metal cylinder wrapped in tin foil. The device had two elements in the form of a membrane connected to a needle - one for recording and one for reproduction. When someone spoke in a shout, sound vibrations acted on the recording needle, and it left grooves of various depths on the cylinder. Edison gave a sketch of the device diagram to his mechanic John Kreusi, and he allegedly built the car in 30 days.

Edison immediately tested the car, reciting a nursery rhyme “Mary had a lamb” in a shout. To his surprise, the device reproduced what he said. Although it was claimed that this event occurred on August 12, 1877, some historians believe that perhaps this happened a few months later, because Edison did not file a patent application until December 24, 1877. Also, in Charles Batchelor’s diary, one of Edison’s assistants, contains a record saying that the phonograph began to be constructed on December 4, and finished it two days later. A phonograph patent (# 200,521) was granted on February 19, 1878. The invention was very original. The only mention of such an invention was found in the work of the French scientist Charles Cros (Charles Cros), which he wrote on April 18, 1877.

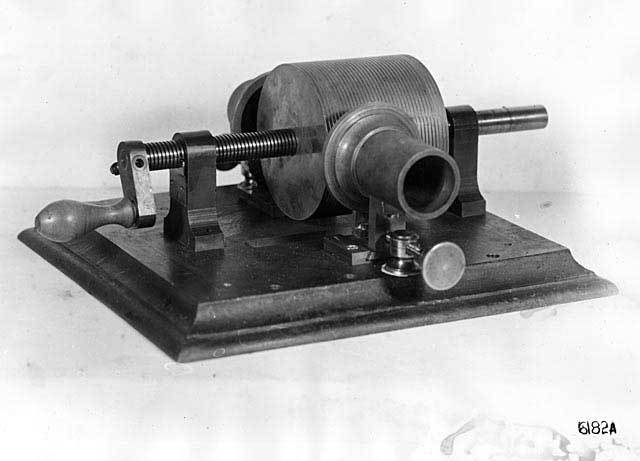

The original Edison phonograph (tin foil used in the design). Photo courtesy of the US Department of Homeland, the National Parks Service and Edison National Historic Site.

Edison brought his new invention to the Scientific American office in New York and demonstrated its work. The December 22, 1877 issue had an article: “Mr. Thomas Edison recently came to our office, put a small device on our desk, turned the knob, and the device asked about our health, asked if we liked the phonograph, talked about its advantages, and kindly wished us good night. " The device aroused great interest, and it was reported in several New York newspapers, and later in other American newspapers and magazines.

On January 24, 1878, Edison founded The Edison Speaking Phonograph, and earned money by showing people a phonograph. Edison earned $ 10,000 by selling manufacturing rights, and also received 20% of sales. The novelty was incredible success, but only experts could work with the device, and the foil was enough for only a few reproductions.

In an interview for North American in June 1878, Edison talked about possible applications of the phonograph:

- Dictation and recording of letters without the help of stenographers.

- Talking books to be read for blind people.

- Speech training.

- Playing music.

- “Family Records” - records of aphorisms and memories of family members in their own voices, the last words of the dying and much more.

- Music boxes and toys.

- A clock that will notify you of lunch time, the end of the working day, and much more.

- Preservation of languages, by accurately reproducing the manner of speech.

- Educational goals; for example, recording material given by the teacher so that the student can always turn to them. Recording spelling lessons or any other for easy memorization.

- An auxiliary device connected to the telephone to transmit short multiple information in order to avoid monotonous short-term calls.

Over time, the device came into use, and Edison did not make any improvements to the design of the phonograph, instead he focused on creating an incandescent lamp.

Since Edison left work on the phonograph, others began to improve it. In 1880, Alexander Graham Bell received the $ 10,000 Volta Prize from the French government for inventing the telephone. Bell used the money he won to create a laboratory for further research on electrical and acoustic phenomena. He worked with his cousin Chichester A. Bell, a chemical engineer, and Charles Sumner Tainter, a scientist and mechanic. They slightly improved Edison’s invention by using wax instead of tin foil and replacing the recorder’s fixed needle with a moving pen that cut through the wax instead of pushing the grooves on the foil.

The patent was awarded to C. Bell and Taint on May 4, 1886. The device was presented to the public as a graphophone. Bell and Taint sent representatives to Edison to discuss possible collaboration to improve the device, but Edison refused and decided to do it on his own. At this point, he had already completed the creation of an incandescent lamp and now could resume his work on the phonograph. Edison called the improved invention the New Phonograph, in which he also used Bell and Taint's wax cylinders.

Edison's phonographic company, The Edison Phonograph Company, was founded on October 8, 1887, to sell Edison's car. He introduced the Improved Phonograph in May 1888, immediately followed by the Perfect Phonograph. The first wax cylinders Edison used were white and made from ceresin, beeswax and stearin wax.

Edison's Home Phonograph

Entrepreneur Jesse H. Lippincott took control of the phonographic companies by purchasing the Edison Phonographic Company and becoming the sole licensee of the American Graphophone Company. Agreeing with other phonographic companies, he founded the North American Phonograph Company (July 4, 1888). Lippincott saw the potential of phonographs only from a financial point of view, and leased them to various partner companies as text dictation machines. Unfortunately, the business was not very profitable, because it could not compete with the stenographers.

Meanwhile, in 1890, Edison's factory made talking dolls for a company of phonographic toys (Edison Phonograph Toy Manufacturing Co). These dolls used tiny wax cylinders. Today it is very difficult to find such dolls, since Edison stopped working with the company in 1891. The phonographic plant also produced musical cylinders for jukeboxes, which began to be used in some subsidiaries. Prototypes of jukeboxes have shown that entertainment is the future of phonographs.

In the fall of 1890, Lippincott fell ill and transferred control of the North American phonographic company to Edison, who was his main creditor. Edison made several changes to the company's policy - one of the changes was the decision to start selling phonographs, rather than renting them out.

Edison increased cylinder production for recreational purposes. In 1892, these cylinders were made of wax, today known among collectors as “brown wax”. Although the word “brown” appeared in the name, the color of the cylinders could vary from dirty white to light brown or dark brown. The name, contractor and manufacturer were indicated on the edge of the cylinder.

[Left: An advertising poster with the Edison Phonograph of the new standard in Harper Magazine, September 1898]

[Left: An advertising poster with the Edison Phonograph of the new standard in Harper Magazine, September 1898]In 1894, Edison declared bankruptcy of the North American phonographic company, which allowed him to buy back the rights to his invention. It took two years to resolve the bankruptcy case, so that Edison could further advance his invention. A spring-loaded Edison phonograph appeared in 1895, although at that time Edison was not allowed to sell phonographs due to a bankruptcy agreement. In January 1896, he founded the National Phonograph Company, which produced phonographs for home and entertainment purposes. Over three years, the company’s branches have spread throughout Europe. In 1896, under the auspices of the company, he announced a spring motor phonograph, followed by Edison's home phonograph, and began to produce cylinders. A year later, Edison’s standard phonograph was created, presented in the press only in 1898. It was the first phonograph created to promote a new brand. Compared to earlier versions of phonographs, their prices have decreased. For the standard model they asked for $ 20, instead of $ 150, as in 1891, and for the model known as GEM (gem), presented in 1899 - $ 7.50.

The cylinders of the standard phonograph were 4.25 inches long and 2.1875 inches in diameter, when played, they rotated at a speed of 120 rpm, and cost 50 cents each. Among the records on the cylinders one could find: marches, sentimental ballads, Negro songs, hymns, comic monologues and reconstructions of the events that took place.

Early cylinder models had two major flaws. First, the short cylinder length limited the recording time to 2 minutes, which narrowed the scope of its application. The second drawback was that there was no way to create a large number of cylinder copies. To record several cylinders, the artists were forced to repeatedly repeat their performances. This recording method not only took a long time, but was also very expensive.

Edison Concert Phonograph, with a louder sound and enlarged cylinders 4.25 inches long and 5 inches in diameter, was introduced in 1899 at a price of 125 dollars. The cost of the cylinders for him was set at $ 4. The sales of the concert phonograph were low, and as a result, the price was reduced. Production was stopped in 1912.

[Left: A catalog of records for Edison's cylinders, September 1911]

[Left: A catalog of records for Edison's cylinders, September 1911]Mass production of copies of wax cylinders was launched in 1901. The grooves on the cylinders were smelted, not cut with a pen, and harder waxes were used. The process was compared to the melting of gold, due to the gold vapor rising from the gold-plated electrodes used in the process. Molds were made using the reference sample, which were already used for the manufacture of cylinders. In one form, it was possible to create from 120 to 150 cylinders per day. The new wax used in the manufacture of the cylinders was black in color and at first they were called “new high-speed records melted from solid wax”, but later the name was changed to “Cast from gold”. In mid-1904, the development of mass production allowed to reduce the price of cylinders to 25 cents per piece. The beveled ends were made to accommodate the titles.

A new phonograph for business was introduced in 1905. It looked like a regular phonograph, but underwent changes in the structure of the speaker and reading needle. Early models of the device were difficult to use, and their fragility often led to breakdowns. Although a few years later the device was improved, it still cost more than the popular inexpensive Columbia recorders. Later, controls and electric motors were added to the Edison phonograph design, which improved the performance of the device. (Some of Edison's phonographs, released before 1895, also had electric motors, but they were replaced by spring motors).

After the modifications, the phonograph for Edison's business turned into a system for dictating text. The system used three devices: a dictating machine, a secretary machine for typing, and a cylinder replacement unit. This system can be seen in the commercial for Stenographer's Friend, filmed by Edison in 1910. The improved Edifon device was introduced in 1916, and its sales after the First World War grew steadily, up to the 20s of the XX century.

[Left: Cast Records Catalog, March 1903]

[Left: Cast Records Catalog, March 1903]In terms of playback time, 2-minute wax cylinders could not compete with competitors' disks, which allowed them to play recordings lasting up to 4 minutes. In November 1908, an Amberol Record cylinder was presented as an answer to the disks, in which the playback time increased to 4 minutes due to thinner grooves. Over time, 2-minute cylinders became known as Edison's two-minute recordings, which later became known as Edison's standard recordings. In 1909, a batch of Grand Opera Amberols cylinders (as the heir to the two-minute Grand Opera cylinders introduced in 1906) was launched to attract influential customers, but this attempt was unsuccessful. In 1909, the phonograph Amberola I was introduced to the public. It was assumed that this luxury model with high quality reproduction, compete with models like Victrola and Grafonola. In 1910, the company was reorganized into the Thomas Edison Corporation (Thomas A. Edison, Inc). Frank L. Dyer was its first president, after which Edison became president and served from December 1912 until August 1926. After Edison, his son Charles became president and Edison remained chairman of the board of directors.

Columbia, one of Edison’s main competitors, left the cylinder market in 1912. (Columbia refused to produce their own cylinders in 1909, and until 1912 they sold cylinders purchased from Indestructible Phonographic Record). The United States Phonograph discontinued its USEverlasting brand in 1913, leaving the market for Edison. The disc has been steadily gaining popularity among buyers, especially thanks to artists who recorded their albums at Victor Studios. Edison did not give up the cylinders and presented instead of the Blue Amberol Record a cylinder that did not wear out over time and provided the best sound that could be achieved at that time. The finer sound of the cylinder is partly due to its constant rotation speed at all points,

Edison was proven that a vertical groove cut produces a better sound than a side cut from Victor and other disc manufacturers. At that time, the cylinders found their regular audience, but could no longer compete with the discs, and even the best sound of the Blue Amberol cylinders could not increase the demand for them. Edison surrendered to the passage of time in 1913 when he announced Edison's disk phonograph. Edison's company did not forget the loyal customers of the cylinders and produced Blue Amberol cylinders until the company ceased to exist in 1929, although most of them were copies from Edison's diamond disks.