The defeat of robots: the ups and downs of high-frequency trading (Part 1)

- Transfer

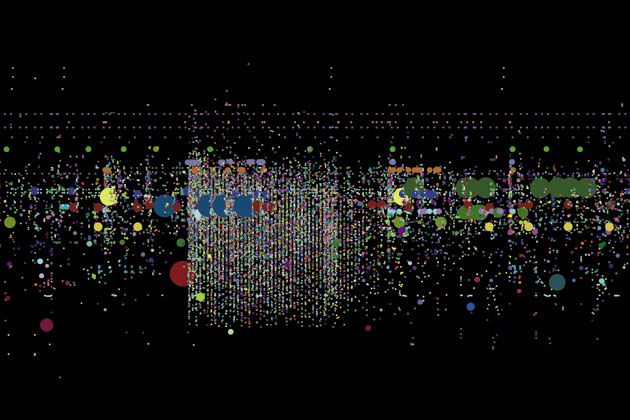

San Francisco-based Stamen teamed up with Nasdaq to visualize the frantic pace of automated bidding. The figure illustrates the buy and sell requests sent by the algorithms in just one minute (the illustration shows the trades on March 8, 2011)

Steve Swanson was a typical 21-year-old computer geek with very atypical work. It was in the summer of 1989, and he had just earned a math degree at Charleston College. In clothes, he was attracted to t-shirts and slippers, and on television - the series Star Trek. He spent most of his time in the garage of Jim Hawkes, a statistics professor at the college where Steve studied. There, he programmed the algorithms in order to subsequently become the first company in the world conducting high-frequency trading, and will receive the name Automated Trading Desk. Hawks was haunted by the obsession that stocks could be profitable using price prediction formulas developed by his friend David Whitcomb, who taught economics at Rutgers University.

A satellite dish mounted on the roof of the Hawks garage caught signals carrying information about quotation updates, receiving which the system could predict the behavior of prices in the markets within the next 30-60 seconds and automatically bought or sold shares. The system was named BORG, short for Brokered Order Routing Gateway, Brokerage Team Routing Gateway. The name bore a reference to the Star Trek series, and more specifically to the evil alien race, capable of absorbing entire species, turning them into parts of a single cybernetic mind.

One of the first victims of BORG was market makers from exchange rooms who manually filled out cards with information about buying and selling shares. ATD not only knew better who gives a more attractive price - the new system carried out the process of buying / selling shares in a second - by today's standards, this is a terrible speed, but then no one could surpass it. As soon as the stock price changed, the ATD computers began to trade on terms that the rest of the market had not yet had time to adjust, and a few seconds later the ATD sold or bought shares again at the “right” price. Back then, Bernie Madoff was the largest Nasdaq market maker (NDAQ).

“Madoff hated us,” says Whitcomb. "In those days, we managed to leave him with his nose."

On average, fewer pennies per share came from ADT, but the company worked with hundreds of millions of shares per day. As a result, the firm managed to move from Hawks' garage to a modern $ 36 million business center in the marshy suburb of Charleston, South Carolina, about 650 miles from Wall Street.

By 2006, the company was trading approximately 700-800 million shares per day, representing over 9 percent of the total US stock market. And she had competitors. A dozen other large electronic trading companies entered the scene: Getco, Knight Capital Group, Citadel grew out of the trading floors of the commodity and futures exchanges in Chicago and the New York stock exchanges. High Frequency Trading (HFT) began to gain momentum.

Depending on who you ask, you will be given different definitions of high-frequency trading. Essentially, this is the use of automated strategies to process large volumes of stock buy / sell teams in a split second. Some firms may transact in securities in microseconds (as a rule, such companies trade for their own benefit, and not for customers). However, high-frequency trading is not only good for stock trading: HFT-traders have already conquered the futures markets, fixed income securities and the foreign exchange market. The options market is still holding defense.

Depending on who you ask, you will be given different definitions of high-frequency trading. Essentially, this is the use of automated strategies to process large volumes of stock buy / sell teams in a split second. Some firms may transact in securities in microseconds (as a rule, such companies trade for their own benefit, and not for customers). However, high-frequency trading is not only good for stock trading: HFT-traders have already conquered the futures markets, fixed income securities and the foreign exchange market. The options market is still holding defense.Let us return to 2007: the "traditional" trading companies are trying their best to automate their activities. Citigroup buys ATD for $ 680 million this year. Svenson, already a forty-year-old man, becomes the head of Citi's electronic securities trading department and is embarking on the integration of ATD systems in Citi's banking sector around the world. By 2010, high-frequency trading is working with more than 60% of the total US stock market and, apparently, is preparing to absorb the remaining 40%. Svenson, tired of bureaucrats at Citi, leaves the company and in mid-2011 opens his own HFT company. A private company, Technology Crossover Ventures, offers him tens of millions of dollars to open a trading firm, which he calls Eladian Partners. If all goes well, already in 2012, TCV will close a new multi-million dollar round of investment. But things did not go as planned.

For the first time since its inception, HFT companies, a living nightmare of all markets, have been defeated. According to Rosenblatt Securities, between 2008 and 2011, approximately two-thirds of all trading in the US stock market was conducted by high-frequency traders - now this figure has dropped to 50%. In 2009, high-frequency traders worked daily with approximately 3.25 billion shares per day. In 2012, this amount decreased to 1.6 billion. HFT traders not only began to work with fewer stocks, they began to receive less profit from each trading operation. Sector average earnings fell from one tenth to one twentieth of singing per share.

According to Rosenblatt, in 2009 the entire HFT trading industry earned $ 5 billion in stock trading. Last year, these numbers reached just $ 1 billion. For comparison, JPMorgan Chase earned six and a half times more in the first quarter of this year alone.

“Our revenue has plummeted,” said Mark Gorton, founder of Tower Research Capital, one of the largest and fastest HFT firms.

“The time of easy money has passed. We are doing many things better now than ever, but we get less for it than before. ”

“Trading margin does not cover our costs,” said Raj Fernando, executive director and founder of Chopper Trading, a large Chicago-based company using high-frequency trading strategies.

“Now no one goes to the bank with a smile, that's for sure.”

A considerable number of HFT companies closed last year. According to Fernando, before going out of business, many of these companies asked Chopper to purchase them. He did not accept a single offer.

One of the tasks of high-frequency trading was to increase the efficiency of markets. High-frequency traders have done so much work, reducing the number of unproductive operations when buying and selling shares, that now it was not so easy for them to make money themselves. In addition, there is now a shortage of two factors on the markets that HFT companies need most - and this is an increase in stock markets and volatility. Compared to the deep, volatile market trends of 2009-10, the modern stock market is more like a paddling pool for children. Trading volumes in the US stock markets today amount to about 6 billion shares per day - this figure is almost no different from the 2006 figure. Volatility, an indicator of share price volatility, has halved compared to last year. Finding out the price difference in stock markets, high-frequency traders thereby guarantee that when the situation gets out of control, they themselves will quickly bring it back to normal. As a result, they “dampen” volatility, preventing the two of their most frequently used strategies: market-making and statistical arbitrage.

One of the tasks of high-frequency trading was to increase the efficiency of markets. High-frequency traders have done so much work, reducing the number of unproductive operations when buying and selling shares, that now it was not so easy for them to make money themselves. In addition, there is now a shortage of two factors on the markets that HFT companies need most - and this is an increase in stock markets and volatility. Compared to the deep, volatile market trends of 2009-10, the modern stock market is more like a paddling pool for children. Trading volumes in the US stock markets today amount to about 6 billion shares per day - this figure is almost no different from the 2006 figure. Volatility, an indicator of share price volatility, has halved compared to last year. Finding out the price difference in stock markets, high-frequency traders thereby guarantee that when the situation gets out of control, they themselves will quickly bring it back to normal. As a result, they “dampen” volatility, preventing the two of their most frequently used strategies: market-making and statistical arbitrage.Companies market makers "revive" the process of bidding, asking for quotes for both purchase and sale. They profit from the spread, which now barely exceeds one penny per share, so these companies need to work with large volumes of shares in order to stay afloat. Companies choosing arbitrage strategies make money at a negligible price difference between related assets. If Apple (AAPL) stocks are being traded at different prices on any of the 13 US stock exchanges, HFT companies will buy cheaper or sell more expensive stocks. The stronger the price changes, the greater the likelihood that a price difference will appear on the market. As price fluctuations slowed, arbitrage trading became less profitable.

To be continued…