Ask Ethan No. 15: The Biggest Black Holes in the Universe

- Transfer

As we descend into the abyss, we learn the treasures of life. Where you stumble there you will find your jewel.

- Joseph Campbell

The reader asks:

Observing distant quasars, we see their supermassive black holes weighing 10 9 solar. How do they manage to reach this size in such a short time?

This problem is more complicated than it seems at first glance. You need to start with astrophysics.

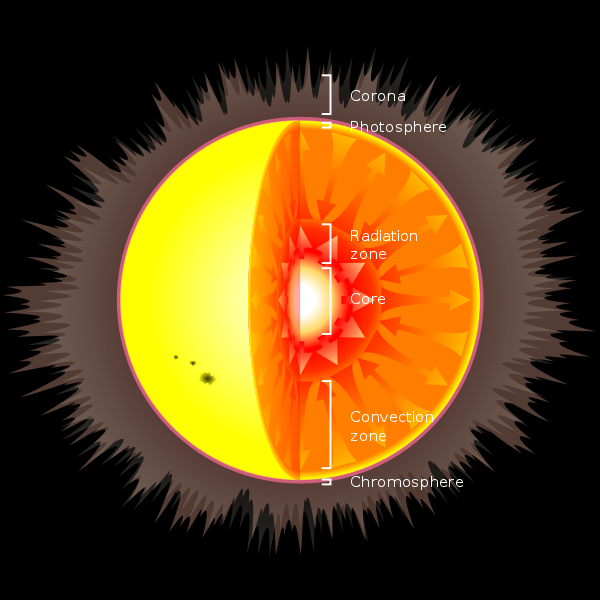

You may already know that stars come in different sizes and colors, with different lifespan and masses, and that all these properties are related to each other. The larger the star, the larger its core, in which, according to the principles of nuclear fusion, its fuel burns. This means that more massive stars burn more brightly, at higher temperatures, they have a larger radius and they also burn faster.

If a star, like our Sun, can take more than ten billion years to burn all its fuel in the core, then the stars can be tens or even hundreds of times more massive than our Sun, and instead of billions of years, they can synthesize all the hydrogen in the core into helium in several million, and in some cases, even over several hundred thousand years.

What happens to the core when it burns its fuel? It should be noted that the energy released during these reactions is the only thing that holds the nucleus against the huge gravitational force, which constantly works to compress all the matter in the star to the smallest possible volume. When these fusion reactions stop, the core shrinks quickly. Compression speed matters because if you compress matter slowly, the temperature will remain constant, but it will increase entropy; and if you compress it quickly, then the entropy will be constant, and the temperature will increase.

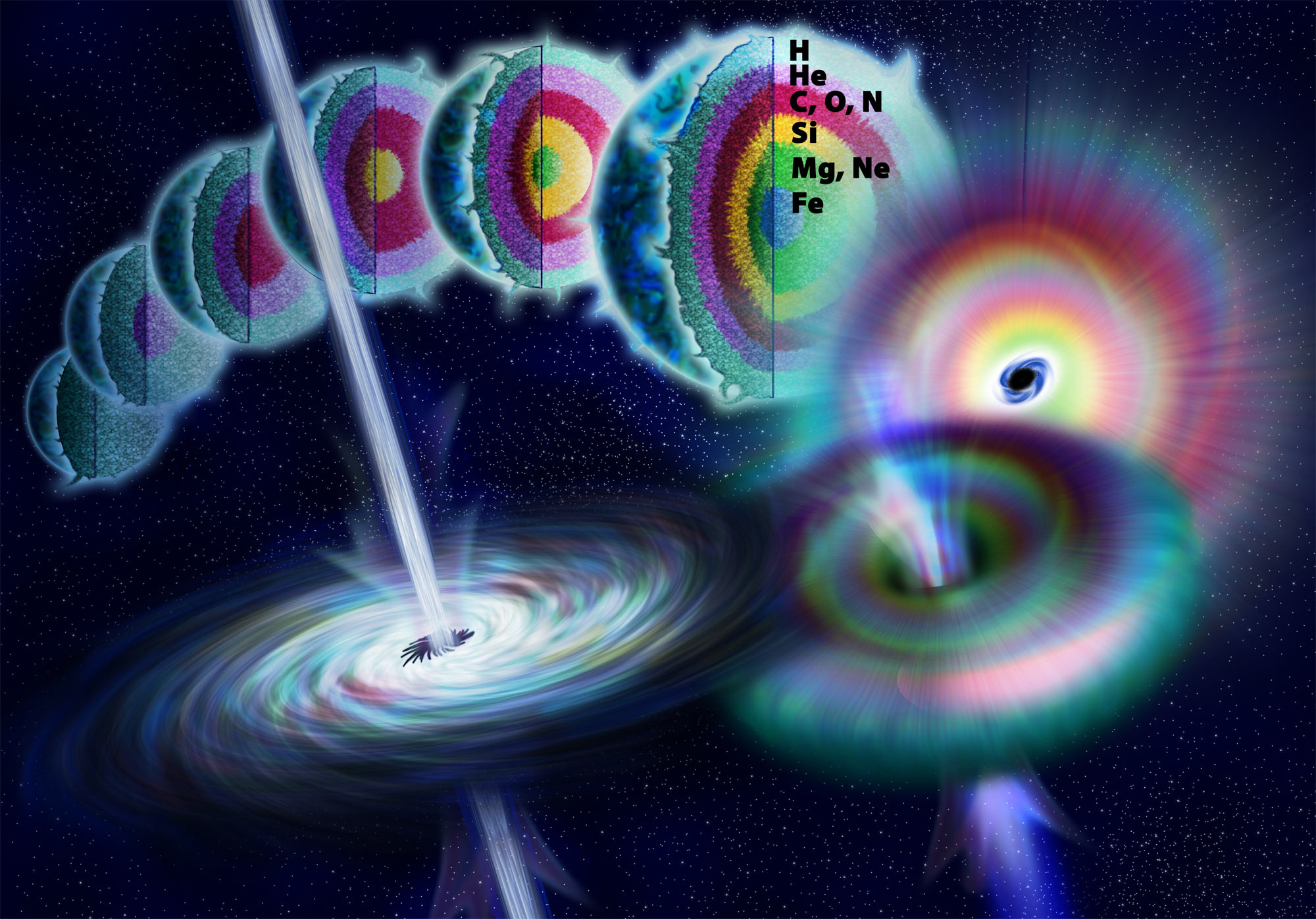

In the case of massive stars, an increase in temperature means that the star can begin to synthesize more and more heavy elements, starting from helium, passing through carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, neon, magnesium, silicon, sulfur, and finally approaching iron, nickel and cobalt. Note that these elements form with an increase in nuclear number by 2, due to the fact that helium combines with existing elements. And when you get to iron, nickel and cobalt, the most stable elements, then further synthesis becomes impossible, and the nucleus explodes outward, turning into a type 2 supernova.

If this does not happen in a very massive star, you will get the nucleus of a neutron star. And if you take a more massive star, with a heavier core, then it will not withstand gravity and create a black hole inside itself. A star 15-20 times the size of the Sun is likely to create a black hole in the center after its death. And more massive stars will create more massive black holes. One can imagine a huge number of fairly massive stars, from which black holes are born that are in a limited space. And then these black holes combine together with time, or both black holes combine and they devour stellar and interstellar matter, which, according to our observations, also happens.

Unfortunately, this does not happen so fast as to coincide with our observations. You see, if a star becomes too massive, a black hole will not appear inside it! If you observe stars with a mass of 130 solar, then the interiors of the stars become so hot and they contain so much energy that the high-energy particles appearing there can form matter-antimatter pairs in the form of positrons and electrons. At first glance, this is not a big deal, but remember what happens in the nuclei of these stars: all that keeps them from collapsing is the pressure exerted from the inside by a study of nuclear fusion. And when pairs of electrons and positrons begin to appear, they are excluded from the present radiation, which leads to a decrease in pressure on the nucleus from the inside.

The core heats up, and it contains a large number of positrons, which annihilate with ordinary matter and produce gamma radiation, which further heats the core. In the end, you get something so energetic that it tears the whole star to shreds, in a very bright and beautiful way. So it turns out a supernova of unstable pairs. This not only destroys the outer layers of the star, but also the core itself, and after this explosion there is absolutely nothing left!

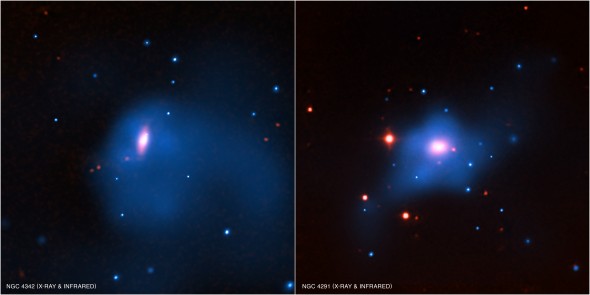

Even without taking into account the sufficiently large black holes that quickly formed in our Universe, we can still get supermassive black holes - such as the one in the center of our galaxy. According to the orbits of the stars orbiting around her, her mass is several million solar masses.

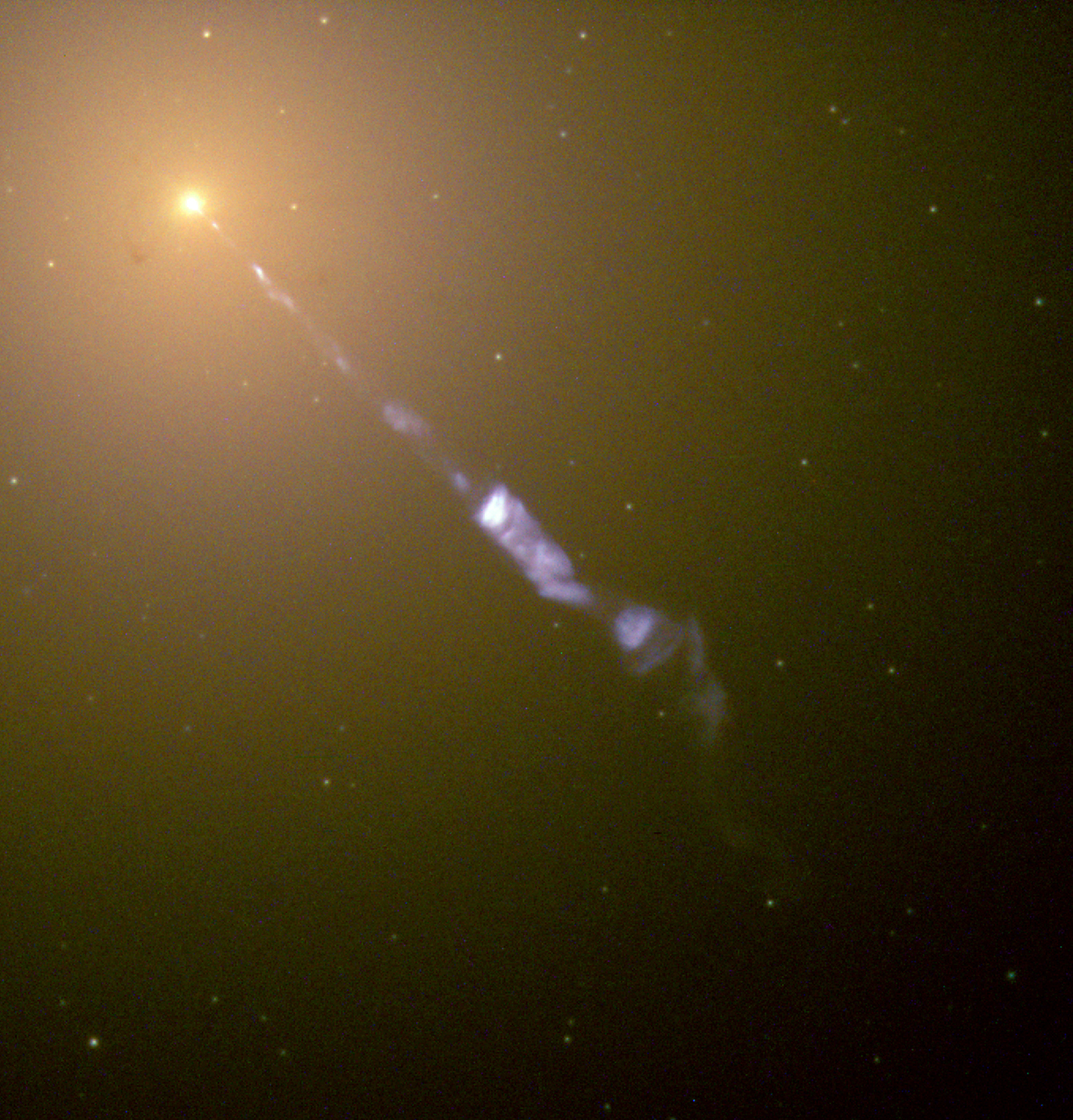

But in this way it is impossible to obtain black holes weighing billions of solar masses, like the one located in the quite distant galaxy Messier 87.

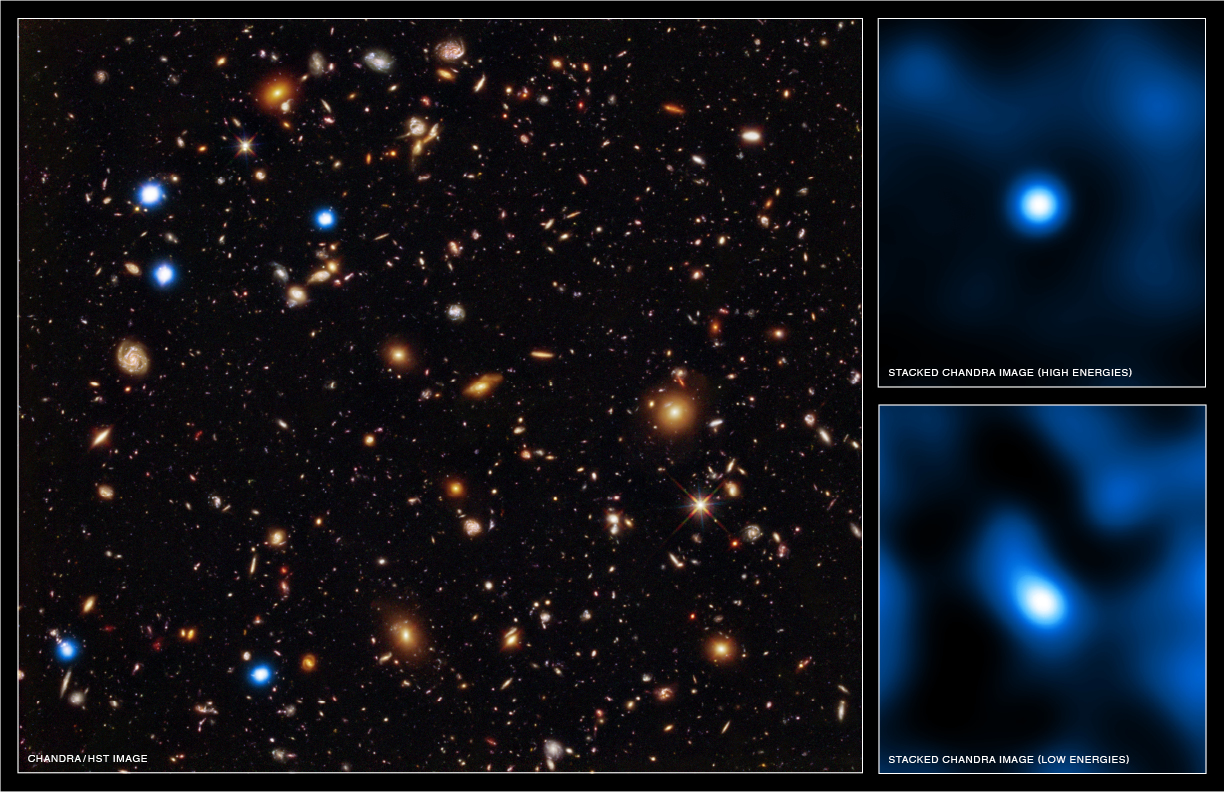

What the reader is asking about is supermassive black holes weighing about several billion solar masses. And they show up with a large redshift, which suggests that they have been very large for a very long time.

You might think that from the very beginning there were already such huge black holes in the Universe, but this does not correspond to what we know about the young universe from the spectral power of matter and from background cosmic radiation. Wherever these supermassive black holes come from, it is unlikely that they were here from the very beginning - but now they can be found even in very young galaxies!

So, if ordinary stars cannot produce such black holes, and the Universe was not born with them, then where did they come from?

It turns out that stars can be even more massive than those we have already talked about. And when they reach huge masses, a new hope appears. Let's go back to the first stars that formed in the Universe from prehistoric hydrogen and helium - the gases that existed then, only a few million years after the Big Bang.

There is a lot of evidence indicating that at that time stars formed in large regions - not like today's star clusters in our galaxy, containing several hundred or thousands of stars. Then large clusters contained millions or even more stars. If we look at the nearest and largest region of star formation in the Tarantula Nebula, located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, we can understand what is happening.

This region of space has 1000 light years across. In its center there is a huge area where new stars are formed - R136. It contains new stars, whose total mass is about 450,000 solar masses. This complex is active, new massive stars form there. And in the center of the central region, you can discover something truly unique: the most massive of all the known stars in the universe!

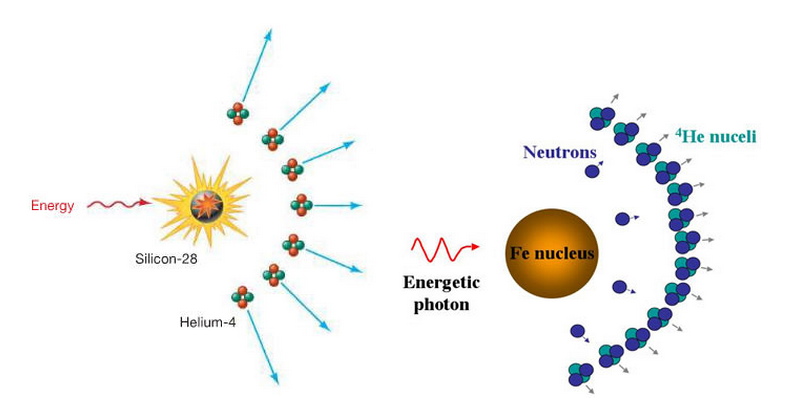

The largest star in the area is 265 times heavier than the sun, and this is a very remarkable phenomenon. Recall that I talked about supernovae unstable pairs, and how they destroy stars that are heavier than 130 solar masses and do not leave black holes behind. This formula works until a certain point - only for stars whose mass is more than 130 solar, but less than 250 solar. And if the mass increases even more, we will receive gamma radiation of such strength that a photonuclear reaction will occur - when gamma rays cool the interior of the star, knocking out heavy nuclei and turning them into light.

If a star has a mass of more than 250 solar masses, it will completely collapse into a black hole. A star with a mass of 260 solar masses can create a black hole with a mass of 260 solar. A star of 1000 solar masses will create a black hole with a mass of 1000 solar masses. And since we can make stars with huge masses in our isolated corner of the cosmos, we can make these objects at a time when the Universe was young. And we most likely made a fairly large number of these objects - and yet they will still be combined.

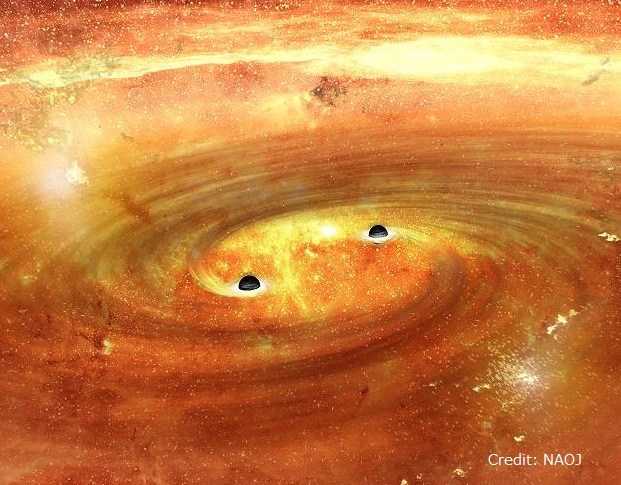

And if it is possible to create an area where a massive black hole of several thousand solar masses was formed just a few million or tens of millions of years after the Big Bang, then the rapid unification and accretion of these regions where stars form, suggests that these early large black holes would uniquely unite with each other. After a short time, they would form larger and larger black holes in the centers of these regions, which then turned into the first giant galaxies of the Universe.

This growth, which continues in time, can easily lead us to modest estimates of black holes weighing several hundred million suns that a galaxy the size of the Milky Way can generate. It is easy to imagine that more massive galaxies and nonlinear effects can increase the probable masses of black holes to billions of solar masses without any problems. And although we do not know for sure, but as far as we can judge from the knowledge that we have, this is how supermassive black holes appear.