How to make presentations, or why not everything takes off? Part 1

Due to my work and, in general, out of a love of art, as well as a great desire to share useful information with others, I quite often have to give presentations to the venerable public at the most diverse, usually IT conferences. Not all of my performances are successful, something works better, something worse. Be that as it may, for several years of practice, some experience has accumulated that I wanted to share, and in connection with this, the eponymous webinar was held on April 12 , the recording of which can be viewed on techdays.ru .

Thinking (not very long), I decided that it would also be nice to share my thoughts in text format: here you can concretize, and it’s better to put them on the shelves, and to read more conveniently for many.

A lot has been written about the preparation and creation of presentations (here I mean both the stage performance and the physical, usually a digital object of creativity) - and at the end I will provide links to several books that seemed interesting to me in the context of the topic under discussion. In my article, I will concentrate on two things:

The first thing to be puzzled is something like this: "What the hell do I have to do anything?" Of course, depending on the context, the wording may change: starting with the banal “why?” or "do I need it?" and ending with the mercantile "what will I get from this?" And ask yourself a similar question is a must. Fair.

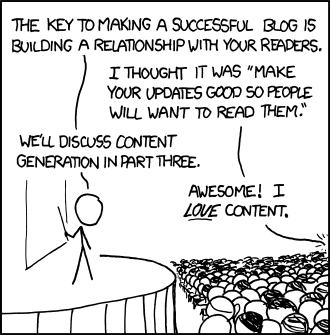

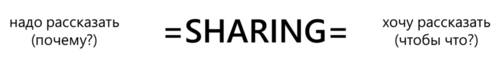

To make it easier to find the answer, here's a quick tip: if you are not a notorious idler who just wants to rub his tongue, thereby satisfying his physiological and mental need, then the key word for you is “sharing”.

Sharing is the exchange, sharing, voluntary flow of fluids and information flows from one place to another. As a rule, the saturating motivation of the report is the fact that you need or want to share something with someone.

As an option: you need to tell something, because your job responsibilities include the preparation of plans and reports, or, say, without the defense of a thesis you are refused to issue a diploma. You want to tell something in order to convince someone of something or make the audience look differently at some things.

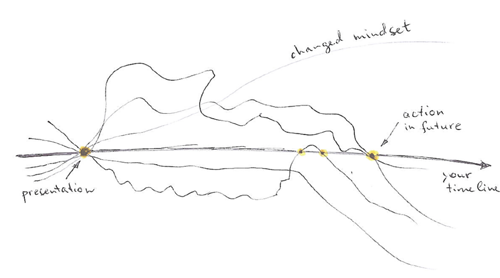

There is a subtle difference between the two questions ( “why?” And “so what?” ). The first is more about introductory, motivating and binding factors ( “share because ...” ), the second is more about motivating and projected for the future ( “share to ...”) In practice, both are often relevant, however, the prevalence of one or the other is also important, since it can determine the presentation format and the restrictions imposed.

For example, a report at a scientific conference or defense of a thesis, as a rule, presupposes a rather strict format of presentation and the corresponding structure of the report and presentation, starting with the statement of the problem and ending with conclusions and future plans. Speaking to investors with a presentation on a given template as a bureaucratic procedure can also involve very specific blocks in the story, usually without kittens and other pranks.

On the other hand, if you share your experience in an informal circle of close friends or speak to colleagues at an industrial it-conference where you can allow yourself freedom or, as they say, you need to work with an audience, then your space for maneuvers is greatly expanded. It can be just a conversation with sketches on napkins, and waving hands without slides. And here you can sometimes be a little disgraceful, of course, in the framework of decency :)

Therefore, I repeat, when preparing for the report, it is important to answer two questions: why do you need to share information and what do you want to achieve this. In principle, you can think about them within the framework of a dichotomy: what you will lose by keeping the secret to yourself, and what you will gain by bringing the light of thought to the masses.

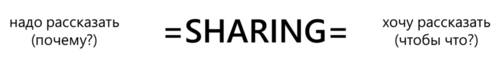

Now that you know the answers to both questions, you are ready to formulate the purpose of your speech. In my opinion, such a goal must necessarily contain exhaust - some result projected onto the future of your listeners.

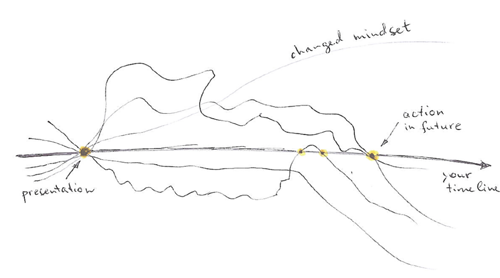

Imagine that the straight line in the center of the image above is a stretch of your life lines. At some point (left point) you tell your report: here your life line intersects with the lines of all your listeners. Next, the presentation will end and your lines will scatter in different directions.

The goal you formulate for your presentation should be about how the life lines of the audience or your own will behave in the future. For example, with your performance, you can provoke their intersections - be it sales, joint projects, other events, or just new useful contacts you can follow on Twitter :) With some of the listeners,

you may never meet directly in your life again , but your presentation may affect their patterns of behavior, way of thinking and attitude to certain objects and circumstances - for example, the image of the company or events in society. Or, another useful exhaust: your own line may change - as a result of feedback during or after the report.

Concretization of future changes in your or external life lines is the goal of your performance.

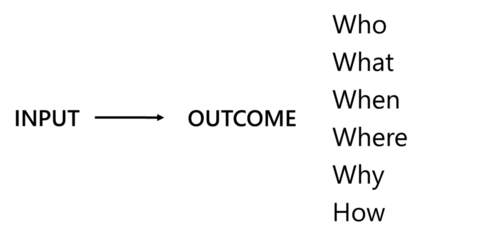

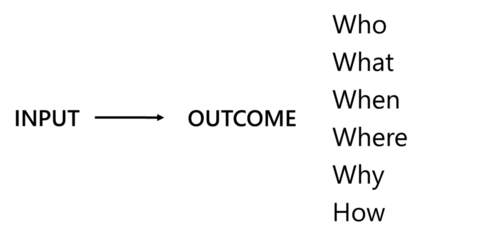

A useful model for formulating the goal is to find the answer in the form of 5W + H: who, what, when, where, why and how. Who are you going to influence? What do you want to change in their lines? When and where should these changes occur? Why will your “who” change their lines and how exactly will they do it?

Of course, in practice, this may turn out to be too difficult an exercise (you probably have itched your pens and opened PowerPoint with the first slide?). Therefore, do not be too zealous in casuistry for answers to strange questions. The simple “I want to share my experience so that the listeners don’t make my mistakes and become better about our company, thinking of it as a progressive it-company” - already sounds quite convincing.

With a goal in mind, it's time to move on to preparing the presentation. Hm. I think it's time to close your PowerPoint and set it aside for a few days. Preparing a presentation is a long and painful process that can drag on for days or even weeks. Of course, if you have so much time. In practice, it also happens that you need to make a presentation “tomorrow”, then this whole process is shortened to several hours, which is not very good, unless you know in advance what exactly you will tell, to whom and why.

I must say that the latter is a completely traditional scenario in the life of an evangelist who needs to convey the same idea to different similar audiences. In such situations, as a rule, it is enough to refresh memory and comb the presentation, taking into account the context, updating individual slides and updating information. As a rule, this means that the preparatory work of serial performances has been carried out earlier - and it does not differ much from everything that I will talk about later.

So, you need to prepare a unique or serial performance. What to do? Get ready!

First of all, you need to immerse yourself in the subject matter of the planned speech, cook in the subject, reason on various related topics, talk with colleagues, collect information, ... do something.

Be distracted, jump freely on related topics, look for parallels.

Your task is to seed your brain, to encourage it to start thinking about the performance and what exactly you will be telling.

From time to time it is important to add spices to the soup and firewood to the fire. Look for tasty details, browse through potentially interesting materials while continuing to “pump” your brain with the topic of your speech. This all strengthens the connections between your neurons and allows the brain to more and more clearly “see” the space for speech: the whole picture as well as individual bright touches of the future history.

While you are shoveling mountains of information or just learning something, possibly related to your topic, but, by the way, it’s not necessary - take notes, write down everything that can come in handy later.

For example, when I was preparing to speak at the “Toaster” conference with a story about the evolution of the web, it so happened that in parallel I read several books about the evolution of wildlife (in particular, “Parasites. The Secret World” by Karl Zimmer), which, in general, intersected well with the topic of the planned report. The more I plunged into both directions, the more I saw interesting analogies that could be drawn between the evolution of various creatures and the evolution of the web.

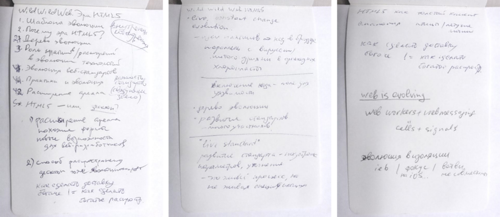

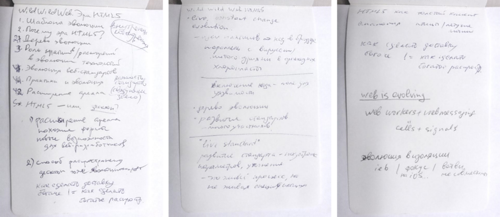

All such interesting things and goodies were recorded in a notebook and marked with bookmarks in the book: Later, individual finds successfully interwoven into a report: At this stage, it is also important to be aware when the cooking process should end and it will be time to proceed to the next steps. If you have time, you can cook. If there are several days left (before the performance, sending slides or any other important control mark), you need to round off.

The next important step is to start talking about the topic of your presentation, to speak both in separate pieces, and try to tell the whole thing that you want to convey to the audience. Moreover, the key task is not to learn to speak, for example, doing this exercise in front of a mirror, but to put in verbal form everything that is spinning in your head. Build verbal form logical connections, transitions, questions and appeals to the audience.

Speak!

Do it yourself with yourself. Discuss individual details with colleagues, friends, acquaintances. Make your brain think about your performance. The more you do this, the more free speech and thought flow will be, and, by the way, the easier it will be for you to answer questions from viewers. Strengthen the connections between the neurons of your brain :)

An important point in “speaking” is that, going through this procedure, you can in practice (your own experience) see and hear the problem points:

Celebrate all such moments for yourself. Simplify your speech and articulate your thoughts more clearly.

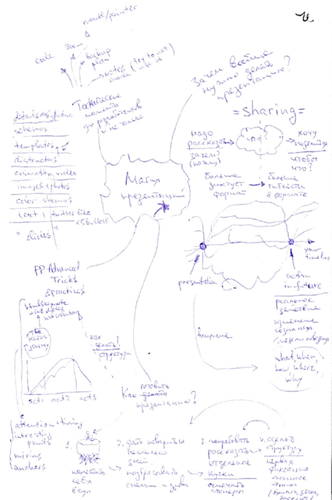

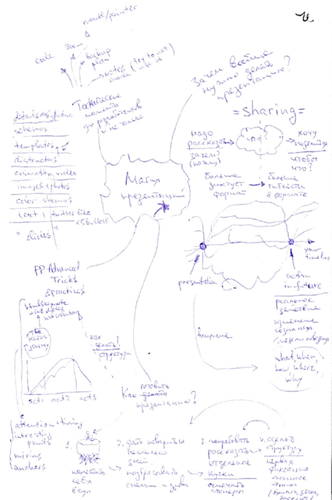

Now that you have more or less a story structure in your head, try to fix it. I usually use simple lists or mindmaps, or other sketchy compositions. As a medium, a regular notepad or sheet of paper, and a whiteboard, and just any application with the corresponding functionality that will not distract you from additional actions are suitable.

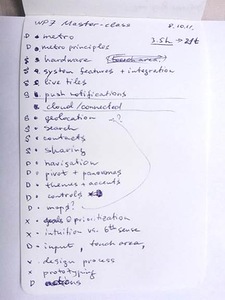

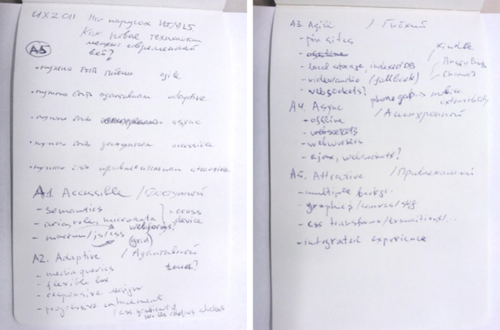

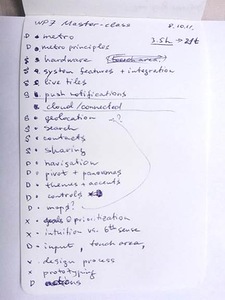

For example, when I was preparing to conduct a design master class for Windows Phone at some point in my notebook there was a list like this:

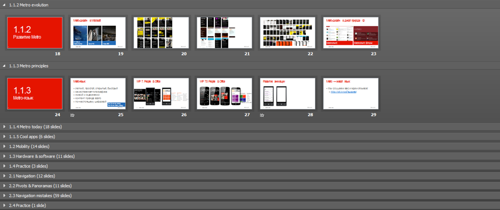

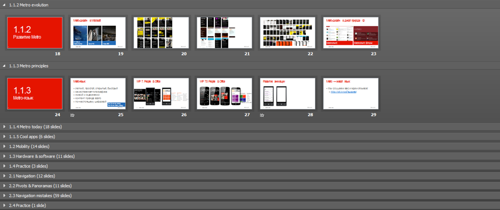

It is important to note key topics, sort, prioritize, arrange the order of presentation and ... figure out the timing. In the example above, I had 3.5 hours for a master class, which could be conditionally divided into 21 slots for 10 minutes (3.5 hours = 210 minutes), respectively, I had to leave about 21 mini-themes.

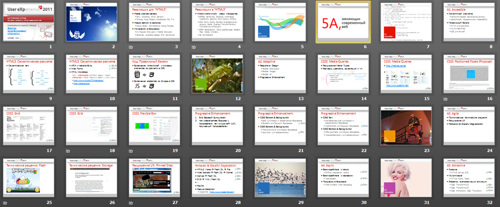

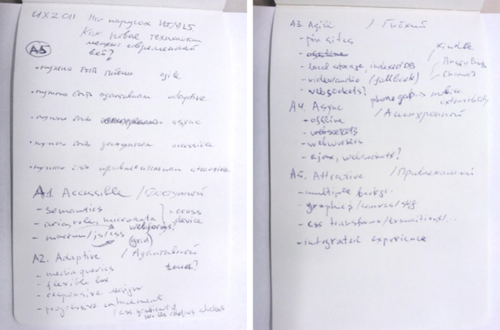

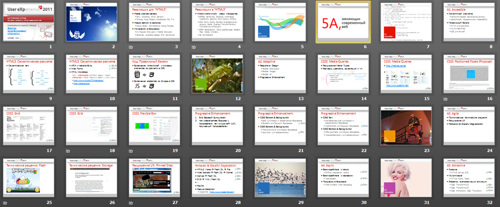

As a result, this also affected the final presentation accompanying the event: Another example: when I was preparing for the report at UserExperience'11 , I already had a fragmentary picture in my head (including due to the fact that I had to make presentations and write articles on similar topics), I wrote in a notebook key topics that quickly transformed into principle 5A (Accessible, Adaptive, Agile, Async, Attractive):

In subsequent stages, it remained to translate this into a presentation and make a report: But here is what the intellect map of this article and the corresponding webinar looked like: So: speak and draw.

Fixation and development are interconnected and mutually supportive processes. It is often difficult to immediately tell the entire contents of the report, or at least fully present it in your head. In this sense, fixing on paper (or another medium) is an excellent tool for the development of thought, as it allows you to visually display the key points of the story. Such supportive phrases and concepts also allow you to keep focus and not get distracted very much from the main exposition.

Therefore, in practice, you can move iteratively: think, talk about the report, fix it. Try to talk more, taking into account the fixed plan - see what happens. Further expand, deepen, make adjustments or rewrite everything completely from scratch. Repeat the cycle until it is ready.

From time to time, you can also return to the second step: to be distracted for a while, broaden your horizons, look for additional details and give the brain the opportunity to continue to think on a topic in a passive mode.

Let's move on!

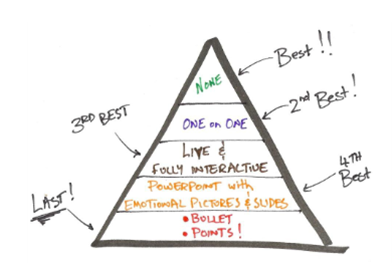

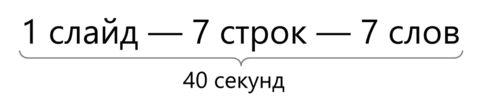

If you were previously interested in the theory (recommendations) for creating presentations, you probably came across such a scheme:

Perhaps you met it in some other variation. For example, you could be told about 5 bullets, the minimum text size and some other “important” parameters.

My practice shows that all this is useful only in the first stages, when you have little experience, since it allows you to avoid very childish stupidities and mistakes. However, further, if you have a head on your shoulders and you are not deprived of sanity, forget: The

truth is that there is no one single and universal approach for all occasions, suitable for all types of presentations. He is simply not there. Therefore, the only thing that can save you is logic, common sense and a sense of taste, backed up by experience.

But if there is, these are some general tips and understanding of some important aspects of the functioning of the living brain. Let's talk a bit about this.

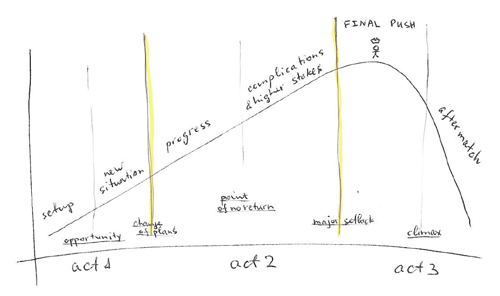

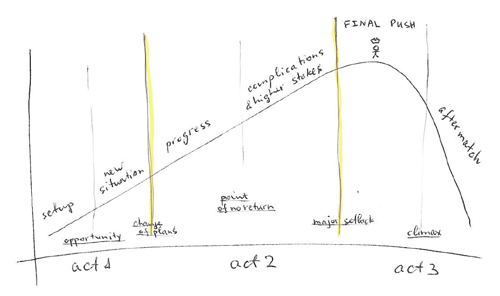

In any work (book, movie, opera, etc.) there is some composition - the structure of the narrative construction, leading the viewer from the beginning to the end of the story, maintaining interest in it and guiding to the key ideas that the author wanted to convey (composer, writer , director, etc.).

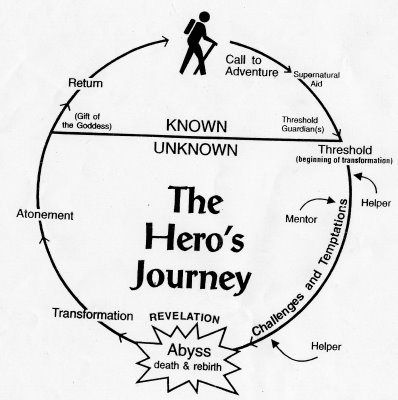

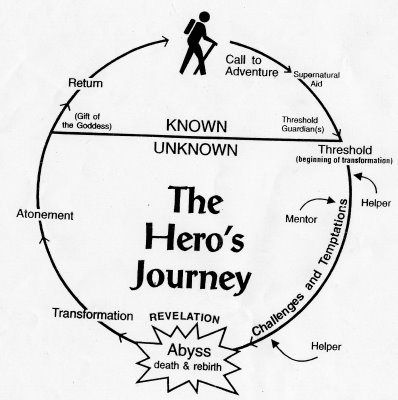

The classical scheme looks like this: In the work, one can conditionally distinguish several acts that describe the introduction to the situation, its development up to the key action and the completion of the story. During his journey, the hero goes through a number of important stages, meets challenges, undergoes transformation, and ultimately wins:

Of course, in practice, the specific outline of one story will always be different from the outline of another. There will be a different plot, different timing and different proportions. Somewhere you will share bitter experience, and somewhere you will find successful solutions. In some cases, you will tell one specific story throughout the story, and in others there will be many small ones connected by some common idea.

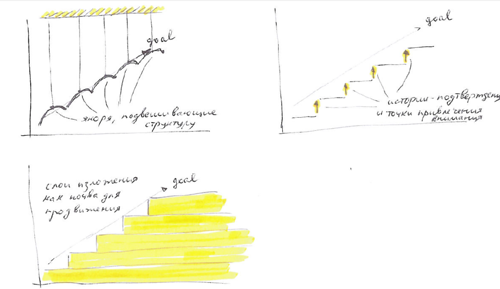

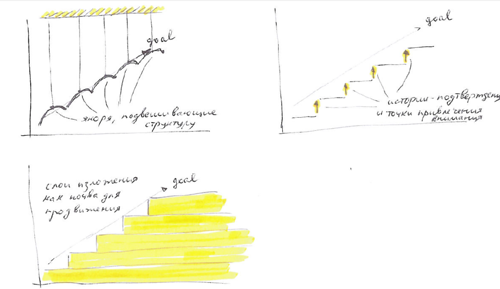

In general, it should be noted that you can look at the composition scheme in different ways, noting for yourself certain important nuances:

Firstly, it turns out to be important to “suspend” the story on some anchors (hooks) that will support the presentation and help the viewer to navigate what is happening and track the dynamics of development. These are reference points that establish the context. In practice, for example, they can be references, reminders of what was told earlier and what role is played by what you are going to tell now. It can also be some cross-cutting line permeating your abstract reasoning.

For example, when I gave a talk on Software People about development under Windows 8, such reference points were visual division into 5 parts (“5 main points that you need to remember”) and the cross-cutting topic “who you need as a team” :

Secondly, for the story to develop towards the main idea of your story (the culmination of the story), you must periodically push the viewer up. These can be both supporting intermediate ideas of history (for example, in a report on the evolution of the web that I talked about above, such stories were analogies with the evolution of wildlife), and some points of attention (attractors) that concentrate the audience’s interest before the next jump.

Thirdly, your story may require a certain sequence of presentation, gradually introducing the listener to the course of things. You will have a foundation in which you can identify the starting point, problems that need to be dealt with, solutions, as alternatives facing the hero, the choice and resolution of the story, as the climax. A kind of pyramid in which each subsequent layer is based on the previous one.

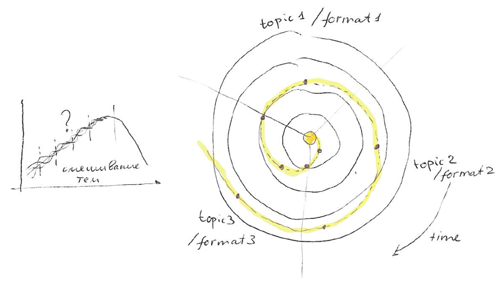

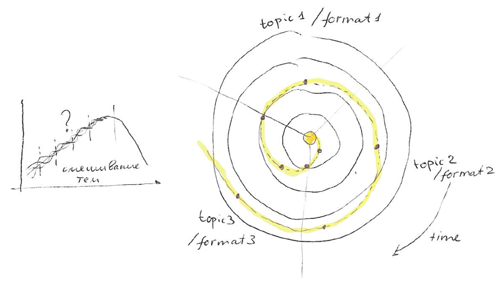

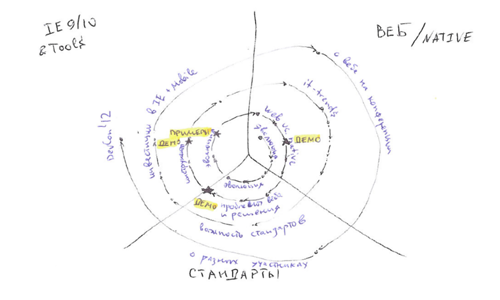

Another important point is the interweaving of stories, when you have parallel storylines, or you need to interweave different manifestations of a key topic or different types of content (for example, pictures, videos, demonstrations, etc.) during a story. In this case, you can consider the line of your story as a spiral, sequentially passing through all the topics that are subject to interweaving into one story. With this approach, you can both clearly track the development of history and make sure that you do not miss the insertion of important related ideas. For example, preparing a key opening report for HTML5Camp :

we kept such a scheme in mind. The main story revolved around the evolution of the web and the juxtaposition of web applications and native applications, leading to the conclusion that the boundaries between these concepts are gradually blurring. The key topics were: web development, web standards and Internet Explorer + development tools.

The story began with the evolution of the web, went on to the evolution of web standards, then projected onto the Internet Explorer development cycle. The second cycle began with the juxtaposition of the web and native development, moving on to challenges on the web and ways to solve problems, projecting onto the capabilities supported by IE and the necessary development tools. The third cycle talked about trends in the IT industry and their intersections with the web, switched to the importance of standardization and ended with investments in IE, including in the mobile version. The final fourth cycle described the conference itself: from different topics and different speakers to a reminder of the next DevCon'12 conference.

In general, our keynotethere was a more or less classical structure, although perhaps this is not immediately obvious from the description above. Gradually moving from one topic to another, including during the demonstrations, the idea developed that today's web is increasingly catching up with the desktop. The climax of the story was at the end of the second cycle, when, summing up the search for answers, Alexander Lozhechkin said that web technologies and the browser not only catch up, but also completely become a platform for native development, hinting at Windows 8. Then followed two short final cycle.

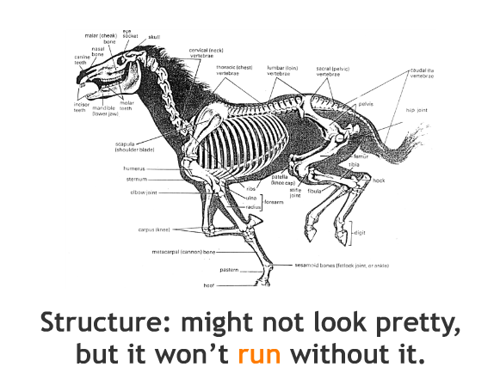

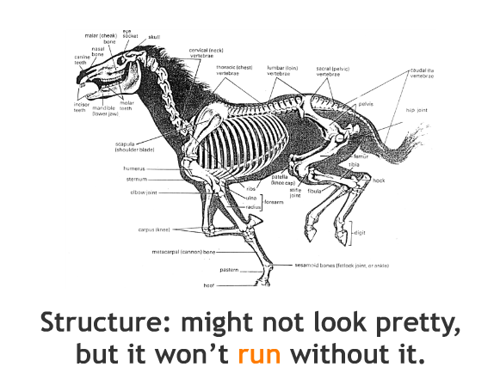

Your structure may differ from the classics. For example, you can invert the presentation by starting with the result and then talking about how and why you came to it. Whatever your presentation, the most important thing is that the structure is in principle:

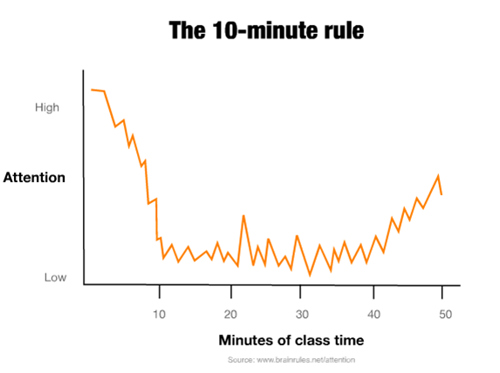

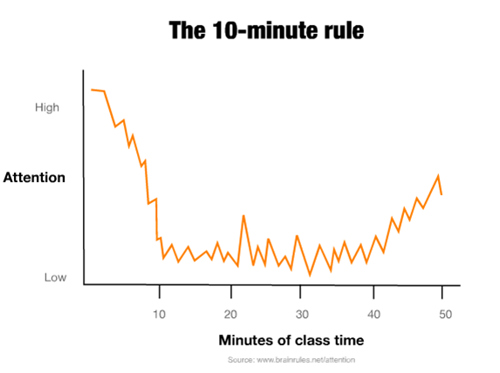

I already mentioned about 10 minutes when I talked about preparing a workshop on Windows Phone. Perhaps you managed to be puzzled, what is the reason for this figure? So, our brain

gets tired when the same thing is shoved into it:

Therefore, from time to time it is necessary to attract the attention of the audience, changing the subject, context, telling stories, moving from words to demonstrations, videos, etc.

Hence an important conclusion: it is necessary not only to build the structure of the story, but also to break it into pieces for about 10 minutes or less, each of which will “re-gain” the attention of the audience. Of course, if only your story lasts more than 10 minutes.

As you know, one and the same thought can be conveyed:

Your idea may turn out to be quite scalable in time, however, its perception by the audience may begin to suffer simply because of the peculiarities of human perception of information. Therefore, as soon as you jump over the threshold of 10-15 minutes of a monotonous story, your viewer begins to fall asleep - and you need to wake him up. In this sense, do not forget to especially mark on the outline of your report those points where you will focus the attention of the audience and make sure that they are enough to maintain interest.

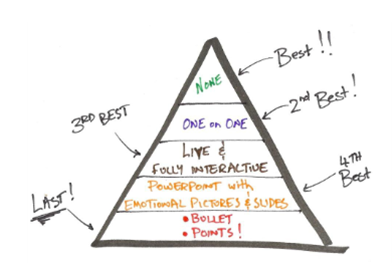

Finally, before we move on (in the second part) to PowerPoint and making presentations, I can't help but recall the Seth Godin pyramid:

History is more important than slides. Yes. If you do not have a single story and no structure, this is bad. Of course, you just can poison the jokes, but this is probably not what your viewers came for. At best, they will remember some good jokes. If you talk too much and get sprayed, it's bad. No one will remember the main thing. If you forget to attract the attention of the audience, everyone will just fall asleep.

Thinking (not very long), I decided that it would also be nice to share my thoughts in text format: here you can concretize, and it’s better to put them on the shelves, and to read more conveniently for many.

A lot has been written about the preparation and creation of presentations (here I mean both the stage performance and the physical, usually a digital object of creativity) - and at the end I will provide links to several books that seemed interesting to me in the context of the topic under discussion. In my article, I will concentrate on two things:

- preparation of the story underlying the presentation, and further elaboration of its structure,

- some aspects and technical nuances that I find useful from a practical point of view when directly creating presentations (slides).

Why do you need to make presentations?

The first thing to be puzzled is something like this: "What the hell do I have to do anything?" Of course, depending on the context, the wording may change: starting with the banal “why?” or "do I need it?" and ending with the mercantile "what will I get from this?" And ask yourself a similar question is a must. Fair.

To make it easier to find the answer, here's a quick tip: if you are not a notorious idler who just wants to rub his tongue, thereby satisfying his physiological and mental need, then the key word for you is “sharing”.

Sharing is the exchange, sharing, voluntary flow of fluids and information flows from one place to another. As a rule, the saturating motivation of the report is the fact that you need or want to share something with someone.

As an option: you need to tell something, because your job responsibilities include the preparation of plans and reports, or, say, without the defense of a thesis you are refused to issue a diploma. You want to tell something in order to convince someone of something or make the audience look differently at some things.

There is a subtle difference between the two questions ( “why?” And “so what?” ). The first is more about introductory, motivating and binding factors ( “share because ...” ), the second is more about motivating and projected for the future ( “share to ...”) In practice, both are often relevant, however, the prevalence of one or the other is also important, since it can determine the presentation format and the restrictions imposed.

For example, a report at a scientific conference or defense of a thesis, as a rule, presupposes a rather strict format of presentation and the corresponding structure of the report and presentation, starting with the statement of the problem and ending with conclusions and future plans. Speaking to investors with a presentation on a given template as a bureaucratic procedure can also involve very specific blocks in the story, usually without kittens and other pranks.

On the other hand, if you share your experience in an informal circle of close friends or speak to colleagues at an industrial it-conference where you can allow yourself freedom or, as they say, you need to work with an audience, then your space for maneuvers is greatly expanded. It can be just a conversation with sketches on napkins, and waving hands without slides. And here you can sometimes be a little disgraceful, of course, in the framework of decency :)

Therefore, I repeat, when preparing for the report, it is important to answer two questions: why do you need to share information and what do you want to achieve this. In principle, you can think about them within the framework of a dichotomy: what you will lose by keeping the secret to yourself, and what you will gain by bringing the light of thought to the masses.

About goals

Now that you know the answers to both questions, you are ready to formulate the purpose of your speech. In my opinion, such a goal must necessarily contain exhaust - some result projected onto the future of your listeners.

Imagine that the straight line in the center of the image above is a stretch of your life lines. At some point (left point) you tell your report: here your life line intersects with the lines of all your listeners. Next, the presentation will end and your lines will scatter in different directions.

The goal you formulate for your presentation should be about how the life lines of the audience or your own will behave in the future. For example, with your performance, you can provoke their intersections - be it sales, joint projects, other events, or just new useful contacts you can follow on Twitter :) With some of the listeners,

you may never meet directly in your life again , but your presentation may affect their patterns of behavior, way of thinking and attitude to certain objects and circumstances - for example, the image of the company or events in society. Or, another useful exhaust: your own line may change - as a result of feedback during or after the report.

Concretization of future changes in your or external life lines is the goal of your performance.

A useful model for formulating the goal is to find the answer in the form of 5W + H: who, what, when, where, why and how. Who are you going to influence? What do you want to change in their lines? When and where should these changes occur? Why will your “who” change their lines and how exactly will they do it?

Of course, in practice, this may turn out to be too difficult an exercise (you probably have itched your pens and opened PowerPoint with the first slide?). Therefore, do not be too zealous in casuistry for answers to strange questions. The simple “I want to share my experience so that the listeners don’t make my mistakes and become better about our company, thinking of it as a progressive it-company” - already sounds quite convincing.

How to prepare a presentation?

With a goal in mind, it's time to move on to preparing the presentation. Hm. I think it's time to close your PowerPoint and set it aside for a few days. Preparing a presentation is a long and painful process that can drag on for days or even weeks. Of course, if you have so much time. In practice, it also happens that you need to make a presentation “tomorrow”, then this whole process is shortened to several hours, which is not very good, unless you know in advance what exactly you will tell, to whom and why.

I must say that the latter is a completely traditional scenario in the life of an evangelist who needs to convey the same idea to different similar audiences. In such situations, as a rule, it is enough to refresh memory and comb the presentation, taking into account the context, updating individual slides and updating information. As a rule, this means that the preparatory work of serial performances has been carried out earlier - and it does not differ much from everything that I will talk about later.

So, you need to prepare a unique or serial performance. What to do? Get ready!

1. Put yourself in the soup

First of all, you need to immerse yourself in the subject matter of the planned speech, cook in the subject, reason on various related topics, talk with colleagues, collect information, ... do something.

Be distracted, jump freely on related topics, look for parallels.

Your task is to seed your brain, to encourage it to start thinking about the performance and what exactly you will be telling.

2. Add spices and firewood

From time to time it is important to add spices to the soup and firewood to the fire. Look for tasty details, browse through potentially interesting materials while continuing to “pump” your brain with the topic of your speech. This all strengthens the connections between your neurons and allows the brain to more and more clearly “see” the space for speech: the whole picture as well as individual bright touches of the future history.

While you are shoveling mountains of information or just learning something, possibly related to your topic, but, by the way, it’s not necessary - take notes, write down everything that can come in handy later.

For example, when I was preparing to speak at the “Toaster” conference with a story about the evolution of the web, it so happened that in parallel I read several books about the evolution of wildlife (in particular, “Parasites. The Secret World” by Karl Zimmer), which, in general, intersected well with the topic of the planned report. The more I plunged into both directions, the more I saw interesting analogies that could be drawn between the evolution of various creatures and the evolution of the web.

All such interesting things and goodies were recorded in a notebook and marked with bookmarks in the book: Later, individual finds successfully interwoven into a report: At this stage, it is also important to be aware when the cooking process should end and it will be time to proceed to the next steps. If you have time, you can cook. If there are several days left (before the performance, sending slides or any other important control mark), you need to round off.

3. Speak

The next important step is to start talking about the topic of your presentation, to speak both in separate pieces, and try to tell the whole thing that you want to convey to the audience. Moreover, the key task is not to learn to speak, for example, doing this exercise in front of a mirror, but to put in verbal form everything that is spinning in your head. Build verbal form logical connections, transitions, questions and appeals to the audience.

Speak!

Do it yourself with yourself. Discuss individual details with colleagues, friends, acquaintances. Make your brain think about your performance. The more you do this, the more free speech and thought flow will be, and, by the way, the easier it will be for you to answer questions from viewers. Strengthen the connections between the neurons of your brain :)

An important point in “speaking” is that, going through this procedure, you can in practice (your own experience) see and hear the problem points:

- blockers in which you do not know what to say or how to formulate a thought;

- loops in which your thought begins to repeat, and you revolve around the same idea and cannot jump further;

- time absorbers in which you start to talk a lot and go too deep into details.

Celebrate all such moments for yourself. Simplify your speech and articulate your thoughts more clearly.

4. Draw a structure

Now that you have more or less a story structure in your head, try to fix it. I usually use simple lists or mindmaps, or other sketchy compositions. As a medium, a regular notepad or sheet of paper, and a whiteboard, and just any application with the corresponding functionality that will not distract you from additional actions are suitable.

For example, when I was preparing to conduct a design master class for Windows Phone at some point in my notebook there was a list like this:

It is important to note key topics, sort, prioritize, arrange the order of presentation and ... figure out the timing. In the example above, I had 3.5 hours for a master class, which could be conditionally divided into 21 slots for 10 minutes (3.5 hours = 210 minutes), respectively, I had to leave about 21 mini-themes.

As a result, this also affected the final presentation accompanying the event: Another example: when I was preparing for the report at UserExperience'11 , I already had a fragmentary picture in my head (including due to the fact that I had to make presentations and write articles on similar topics), I wrote in a notebook key topics that quickly transformed into principle 5A (Accessible, Adaptive, Agile, Async, Attractive):

In subsequent stages, it remained to translate this into a presentation and make a report: But here is what the intellect map of this article and the corresponding webinar looked like: So: speak and draw.

5. Repeat

Fixation and development are interconnected and mutually supportive processes. It is often difficult to immediately tell the entire contents of the report, or at least fully present it in your head. In this sense, fixing on paper (or another medium) is an excellent tool for the development of thought, as it allows you to visually display the key points of the story. Such supportive phrases and concepts also allow you to keep focus and not get distracted very much from the main exposition.

Therefore, in practice, you can move iteratively: think, talk about the report, fix it. Try to talk more, taking into account the fixed plan - see what happens. Further expand, deepen, make adjustments or rewrite everything completely from scratch. Repeat the cycle until it is ready.

From time to time, you can also return to the second step: to be distracted for a while, broaden your horizons, look for additional details and give the brain the opportunity to continue to think on a topic in a passive mode.

Let's move on!

What is important to remember about structure and composition?

If you were previously interested in the theory (recommendations) for creating presentations, you probably came across such a scheme:

Perhaps you met it in some other variation. For example, you could be told about 5 bullets, the minimum text size and some other “important” parameters.

My practice shows that all this is useful only in the first stages, when you have little experience, since it allows you to avoid very childish stupidities and mistakes. However, further, if you have a head on your shoulders and you are not deprived of sanity, forget: The

truth is that there is no one single and universal approach for all occasions, suitable for all types of presentations. He is simply not there. Therefore, the only thing that can save you is logic, common sense and a sense of taste, backed up by experience.

But if there is, these are some general tips and understanding of some important aspects of the functioning of the living brain. Let's talk a bit about this.

Composition

In any work (book, movie, opera, etc.) there is some composition - the structure of the narrative construction, leading the viewer from the beginning to the end of the story, maintaining interest in it and guiding to the key ideas that the author wanted to convey (composer, writer , director, etc.).

The classical scheme looks like this: In the work, one can conditionally distinguish several acts that describe the introduction to the situation, its development up to the key action and the completion of the story. During his journey, the hero goes through a number of important stages, meets challenges, undergoes transformation, and ultimately wins:

Of course, in practice, the specific outline of one story will always be different from the outline of another. There will be a different plot, different timing and different proportions. Somewhere you will share bitter experience, and somewhere you will find successful solutions. In some cases, you will tell one specific story throughout the story, and in others there will be many small ones connected by some common idea.

In general, it should be noted that you can look at the composition scheme in different ways, noting for yourself certain important nuances:

Firstly, it turns out to be important to “suspend” the story on some anchors (hooks) that will support the presentation and help the viewer to navigate what is happening and track the dynamics of development. These are reference points that establish the context. In practice, for example, they can be references, reminders of what was told earlier and what role is played by what you are going to tell now. It can also be some cross-cutting line permeating your abstract reasoning.

For example, when I gave a talk on Software People about development under Windows 8, such reference points were visual division into 5 parts (“5 main points that you need to remember”) and the cross-cutting topic “who you need as a team” :

Secondly, for the story to develop towards the main idea of your story (the culmination of the story), you must periodically push the viewer up. These can be both supporting intermediate ideas of history (for example, in a report on the evolution of the web that I talked about above, such stories were analogies with the evolution of wildlife), and some points of attention (attractors) that concentrate the audience’s interest before the next jump.

Thirdly, your story may require a certain sequence of presentation, gradually introducing the listener to the course of things. You will have a foundation in which you can identify the starting point, problems that need to be dealt with, solutions, as alternatives facing the hero, the choice and resolution of the story, as the climax. A kind of pyramid in which each subsequent layer is based on the previous one.

Mix themes

Another important point is the interweaving of stories, when you have parallel storylines, or you need to interweave different manifestations of a key topic or different types of content (for example, pictures, videos, demonstrations, etc.) during a story. In this case, you can consider the line of your story as a spiral, sequentially passing through all the topics that are subject to interweaving into one story. With this approach, you can both clearly track the development of history and make sure that you do not miss the insertion of important related ideas. For example, preparing a key opening report for HTML5Camp :

we kept such a scheme in mind. The main story revolved around the evolution of the web and the juxtaposition of web applications and native applications, leading to the conclusion that the boundaries between these concepts are gradually blurring. The key topics were: web development, web standards and Internet Explorer + development tools.

The story began with the evolution of the web, went on to the evolution of web standards, then projected onto the Internet Explorer development cycle. The second cycle began with the juxtaposition of the web and native development, moving on to challenges on the web and ways to solve problems, projecting onto the capabilities supported by IE and the necessary development tools. The third cycle talked about trends in the IT industry and their intersections with the web, switched to the importance of standardization and ended with investments in IE, including in the mobile version. The final fourth cycle described the conference itself: from different topics and different speakers to a reminder of the next DevCon'12 conference.

In general, our keynotethere was a more or less classical structure, although perhaps this is not immediately obvious from the description above. Gradually moving from one topic to another, including during the demonstrations, the idea developed that today's web is increasingly catching up with the desktop. The climax of the story was at the end of the second cycle, when, summing up the search for answers, Alexander Lozhechkin said that web technologies and the browser not only catch up, but also completely become a platform for native development, hinting at Windows 8. Then followed two short final cycle.

Your structure may differ from the classics. For example, you can invert the presentation by starting with the result and then talking about how and why you came to it. Whatever your presentation, the most important thing is that the structure is in principle:

And about time

I already mentioned about 10 minutes when I talked about preparing a workshop on Windows Phone. Perhaps you managed to be puzzled, what is the reason for this figure? So, our brain

gets tired when the same thing is shoved into it:

Therefore, from time to time it is necessary to attract the attention of the audience, changing the subject, context, telling stories, moving from words to demonstrations, videos, etc.

Hence an important conclusion: it is necessary not only to build the structure of the story, but also to break it into pieces for about 10 minutes or less, each of which will “re-gain” the attention of the audience. Of course, if only your story lasts more than 10 minutes.

As you know, one and the same thought can be conveyed:

- in one tweet

- short minute "elevator pitch"

- in 5 minutes, as is done in the Ignite Show ,

- in 20 minutes, as in TED ,

- in 30 minutes, 45, an hour, two ...

- etc.

Your idea may turn out to be quite scalable in time, however, its perception by the audience may begin to suffer simply because of the peculiarities of human perception of information. Therefore, as soon as you jump over the threshold of 10-15 minutes of a monotonous story, your viewer begins to fall asleep - and you need to wake him up. In this sense, do not forget to especially mark on the outline of your report those points where you will focus the attention of the audience and make sure that they are enough to maintain interest.

Finally, before we move on (in the second part) to PowerPoint and making presentations, I can't help but recall the Seth Godin pyramid:

History is more important than slides. Yes. If you do not have a single story and no structure, this is bad. Of course, you just can poison the jokes, but this is probably not what your viewers came for. At best, they will remember some good jokes. If you talk too much and get sprayed, it's bad. No one will remember the main thing. If you forget to attract the attention of the audience, everyone will just fall asleep.