Hipster effect: why nonconformists often look the same

- Transfer

The science of complexity explains why attempts to reject conventional wisdom simply lead to new coherence

You probably know this effect - and perhaps you yourself are its victim. You feel the generally accepted culture alien to yourself and want to declare that you are not a part of it. You decide to dress differently, change your hair, apply unconventional makeup or care products.

And yet, when you finally open up your new image to the world, it turns out that you are not the only one - millions of other people have made the same decisions. And you all look more or less the same, which is the exact opposite of the countercultural statement you tried to make.

This is a hipster effect - a counterintuitive phenomenon, as a result of which people who deny a generally accepted culture begin to look the same. Similar processes are taking place among investors in other areas studied by social science.

How does this synchronization happen? Is it inevitable in modern society, and is there a way to truly stand out from the crowd?

Today we get answers thanks to the work of Jonathan Tubula of the University of Brande in Massachusetts. Tubul is a mathematician who studies how the transfer of information in a community affects people's behavior. In particular, he concentrates on a community consisting of conformists who copy the majority, and non-conformists , or hipsters , who try to do the opposite.

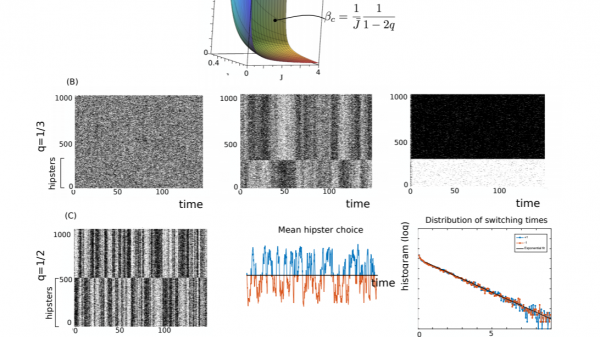

He concluded that in a fairly wide variety of scenarios, the hipster population always experiences a phase transition during which its members synchronize with each other in their opposition to generally accepted norms. In other words, the effect of a hipster is an inevitable result of the behavior of a large number of people.

It is important that the Tubula model takes into account the time required for each individual in order to detect changes in society and react accordingly. This delay is important. People do not instantly react to the appearance of a new, very fashionable pair of shoes. Information is slowly spreading through trendy websites, word of mouth, etc. Distribution delays vary among individuals — some may follow the advice of fashion blogs zealously, others may not have access to them, and they have to rely on rumors.

Tubul is studying the question of under what conditions hipsters are synchronized, and how they change depending on the propagation delay and the proportion of hipsters. To do this, he creates computer models that simulate the interaction of agents, some of which follow the majority, and the other part contradicts him.

This simple model provides surprisingly complex development options. In general, according to Tubul, the population of hipsters at first behaves randomly, but then through a phase transition comes into synchronized state. He discovers that this occurs with a wide variety of parameters, and that this behavior can be very complex, depending on the interaction of hipsters and conformists.

There are some unexpected results. With equal proportions of hipsters and conformists, the entire population is subject to random switching between different trends. Why is this so far unclear, and Tubul plans to study this in more detail.

It can be argued that synchronization grows out of the simplicity of scenarios where a choice of two options is offered. “For example, if most individuals shave their beards, then most hipsters will want to grow it, and if this trend spreads to a large part of the population, this will lead to a new, synchronized transition to shaving,” said Tubul.

With more options available, it’s easy to imagine another development scenario. If hipsters, for example, could grow a mustache, square beard or goatee, then this variety of choices could prevent synchronization. However, Tubul found that if the model offers more than two choices, synchronization still occurs.

And yet he is interested in studying it further. “We will investigate this issue more deeply in our next work,” he said.

Hipsters are easy to make fun of, but the applicability of these results is much wider. For example, they can be useful for understanding financial systems whose participants are trying to make money by making decisions that are opposite to the decisions of the majority of exchange participants.

In fact, there are many areas in which the delay in disseminating information plays an important role. As Tubul says: “Besides the question of choosing the best clothes for the current season, this study may have important consequences for understanding the synchronization of nerve cells, investment strategies, or the manifest dynamics in sociology.”

Continuation of the story from The Register magazine: a hipster complaint and an unexpected denouement

Typically, a headline such as “The Hipster Effect: Why Nonconformists often Look the Same” produces a rolling eye effect. However, the situation becomes more interesting when the hypothesis described in the article is confirmed by amusing correspondence.

In February, MIT Technology Review magazine published a short but meaningful description of 34-page work from experts from the University of Brande. The work, in fact, argued that in an attempt to make a “countercultural statement”, hipsters as a result become similar to each other. Details of an interesting model of how random actions of hipsters lead to a “phase transition to a synchronized state”, as well as complicated network formulas, see here .

The article was accompanied by a photograph from the drain, where the averagea millennial in a plaid jacket and a round hat, or, as Getty describes it , “fashionable winter clothes”. MIT editor, Gideon Lichfield, commented on the implications of posting the article on Twitter, calling them a “warning story”:

“We immediately got a furious email from a man who claimed that he was pictured in a photo illustration of the story. He accused us of slander, probably related to the fact that we called him a hipster, and the use of his portrait without his permission. (He didn’t say too flattering about the story itself either. ”)

Wow, and the words “averaged millennial” are by no means slanderous? Our magazine cannot allow it to be sued because of this article.

Lichfield continued the story:

“As far as I know, calling a person“ hipster ”does not mean slandering him, regardless of the level of his hatred for it. However, we would not use the image without the appropriate rights. It was a stock photo from Getty Images, and we checked its license. "

He said that the license stated that if the image is used “in connection with an unflattering or too controversial topic (such as, for example, sexually transmitted diseases)”, it is necessary to indicate that the model is on the photo.

Lichfield indicated that he did not think that calling someone a hipster would be “unflattering or too controversial,” but he contacted Getty just in case.

The stock giant contacted the model, and it turned out that the comrade in the photo was not the person who complained to the publication. “He just messed himself up with another,” Lichfield said.

“Everything that happened just proves our story: hipsters are so similar to each other that they cannot even distinguish themselves from others.”

Like this. 34 pages of theory have been proven in brief correspondence by email. Your move, hipsters.