DeepMind and Google: the battle for control over strong AI

- Transfer

Demis Hassabis founded the company to create the most powerful AI in the world. Then it was bought by Google.

In August 2010, a 34-year-old Londoner named Demis Hassabis appeared on the stage in a conference room in a suburb of San Francisco. He came out with a leisurely gait of a man who was trying to control his nerves, pursed his lips in a brief smile and began: “So, today we will talk about different approaches to development ...” - he hesitated, as if suddenly realizing that he was voicing secret ambitious thoughts. But then he still said: "... a strong AI."

Strong AI (artificial general intelligence or AGI) means universal artificial intelligence - a hypothetical computer program capable of performing intellectual tasks as a person or even better. A strong AI will be able to perform individual tasks, such as photo recognition or text translation, which are the only tasks of each of the weak AI in our phones and computers. But he will also play chess and speak French. He will understand articles on physics, compose novels, develop investment strategies and conduct delightful conversations with strangers. He will monitor nuclear reactions, manage electric networks and traffic flows and without much effort will succeed in everything else. AGI will make today's most advanced AI look like a pocket calculator.

The only intelligence that is currently capable of performing all these tasks is the one that people are endowed with. But human intelligence is limited by the size of the skull. The strength of our brain is limited by the negligible amount of energy that the body can provide. Because AGI runs on computers, it will not suffer from any of these limitations. Strong intelligence is limited only by the number of processors available. He can start by monitoring nuclear reactions. But it will quickly open up new sources of energy, digesting more scientific work in physics per second than a person can do in a thousand lives. Human intelligence, combined with the speed and scalability of computers, will make problems that currently seem insoluble disappear. In an interview with British ObserverHassabis said, among other things, a strong AI needs to master such disciplines and solve problems such as “cancer, climate change, energy, genomics, macroeconomics [and] financial systems”.

The Hassabis conference was called Singularity Summit. According to futurologists, singularity is one of the most likely consequences of the appearance of AGI. Since it processes information at high speed, it gets wiser very quickly. Fast cycles of self-improvement will lead to an explosion of machine intelligence, leaving people far behind to choke on silicon dust. Since this future is entirely built on the foundation of unverified assumptions, the question of whether singularity is considered utopia or hell is almost religious.

Judging by the names of the lectures at the conference, participants gravitate towards messianism: “Reason and how to build it”; “AI as a solution to the problem of aging”; "Replacement of our bodies"; “Changing the boundary between life and death.” Hassabis’s lecture, on the other hand, doesn’t look very impressive: “A systemic neurobiological approach to building an AGI.”

Hassabis paces between the podium and the screen, saying something quickly. He is wearing a maroon cardigan and a white shirt with buttons, like a schoolboy. A small growth, it seems, only strengthens his intelligence. So far, Hassabis explained, scientists have approached AGI from two sides. In the field of symbolic AI, researchers tried to describe and program all the rules for a system that could think like a person. This approach was popular in the 80-90s, but did not give the desired results. Hassabis believes that the mental structure of the brain is too sophisticated to be described in this way.

Researchers who tried to reproduce the physical networks of the brain in digital form worked in another area. This had a definite meaning. After all, the brain is the receptacle of human intelligence. But these researchers were misled, Hassabis said. Their task turned out to be about the same scale as an attempt to map all the stars in the universe. Moreover, it focuses on the wrong level. It is like trying to understand how Microsoft Excel works by disassembling a computer and studying transistor interactions.

Instead, Hassabis proposed a middle ground: a strong AI should draw inspiration from the broad methods by which the brain processes information, and not from the physical systems or specific rules that it applies in specific situations. In other words, scientists should focus on understanding the software of the brain, not its hardware. New methods, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, allow you to look inside the brain during its activity. They make such an understanding possible. Recent studies have shown that the brain learns in a dream, re-reproducing the received experiences in order to derive general principles. AI researchers must emulate this system.

A logo appeared in the lower right corner of the slide - a round blue swirl. Underneath are two words: DeepMind. This was the first public mention of a new company.

Hassabis spent a whole year trying to get an invitation to Singularity Summit. The lecture was just a cover. What he really needed was one minute with Peter Thiel, the Silicon Valley billionaire who sponsored the conference. Hassabis wanted his investment.

Hassabis never said why he sought to get support precisely from Thiel (for this article, he refused several interview requests through a spokesperson). We spoke with 25 sources, including current and former employees and investors. Most of them spoke anonymously because they did not have the right to talk about the company. But Thiel believes in AGI with even greater fervor than Hassabis. In a speech in 2009, Thiel said that his greatest fear for the future is not a robotic uprising (although in New Zealand, isolated from the whole world, he is better protected than most people). Rather, he fears that the singularity will come too late. The world needs new technologies to prevent an economic downturn.

Ultimately, DeepMind received £ 2 million in venture capital funding; including £ 1.4 million from Thiel. When Google bought the company in January 2014 for $ 600 million, early investors recorded a profit of 5,000%.

For many founders, this would be a happy ending. You can slow down, take a step back and enjoy the money. For Hassabis, the deal with Google was another step in his quest for a strong AI. He spent almost all of 2013 in negotiations on the deal. DeepMind will act separately from the parent company. Hassabis will receive all corporate privileges, such as access to cash flow and processing power, without losing control of the company.

Hassabis thought DeepMind would be a hybrid: he would have a startup drive, the brains of the greatest universities and the deep pockets of one of the richest companies in the world. Everything was done in order to accelerate the development of a strong AI and help humanity.

Demis Hassabis was born in North London in 1976 in the family of a Greek Cypriot and a Chinese-Singaporean. He was the eldest of three brothers and sisters. Mom worked at John Lewis department store, and her father worked at a toy store. The boy learned to play chess at the age of four, watching the game of his father and uncle. After a few weeks, the adults could no longer beat him. By the age of 13, Demis became the second chess player of the world at his age. At eight years old, he independently learned to program.

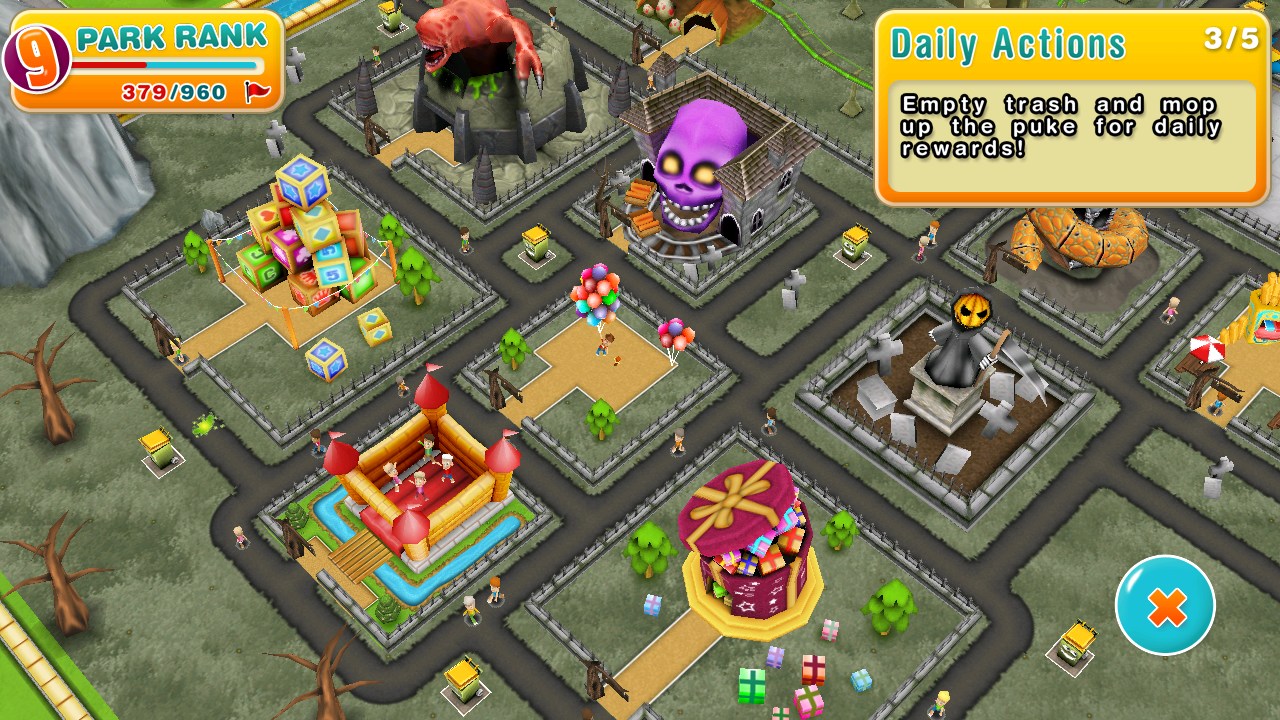

In 1992, Hassabis graduated from school two years ahead of schedule. He got a job programming video games at Bullfrog Productions, where he wrote the game Theme Park. In it, players built and managed a virtual amusement park. The game was very successful with 15 million copies sold. It belonged to a new genre of simulators, in which the goal is not to defeat the enemy, but to optimize the functioning of such a complex system as a business or city.

Theme Park for Android, 2018

Demis not only developed games, but also played great games. As a teenager, he was torn between competitions in chess, scrabble, poker and backgammon. In 1995, while studying computer science at the University of Cambridge, Hassabis got into a student go tournament. This is an ancient board strategy game, which is much more complicated than chess. It is assumed that mastery requires intuition acquired through long experience. No one knew if Hassabis had played before.

First, Hassabis won the tournament for beginners. Then he beat the winner of the tournament for experienced players, albeit with a handicap. Tournament organizer, Cambridge master Charles Matthews remembers the shock of an experienced player after losing to a 19-year-old rookie. Matthews took Hassabis under his care.

Hassabis's intelligence and ambitions have always been evident in games. Games, in turn, aroused his interest in intelligence. Watching his progress in chess, he wondered: is it possible to program computers so that they learn like him, based on experience. Games offered a learning environment that the real world could not match. They were clear and self-sufficient. Since games are separate from reality, they can be practiced without interfering with the real world and mastered effectively. Games speed up time: in a couple of days you can create a criminal syndicate, and the battle on the Somme ends in a matter of minutes.

In the summer of 1997, Hassabis traveled to Japan. In May of that year, IBM's Deep Blue computer defeated world chess champion Garry Kasparov. For the first time, a computer beat a chess grandmaster. The match attracted worldwide attention and raised concerns about the growing power and potential threat of computers. When Hassabis met with the Japanese board game master Masahiko Fujuvarea, he told him about a plan that combines his interests in strategic games and artificial intelligence: one day he will build a computer program that will defeat the greatest player in go.

Hassabis acted methodically: “At the age of 20, Hassabis was of the opinion that certain things must be in place before he engages in AI at the level he wanted,” says Matthews. “He had a plan.”

In 1998, he founded his own gaming studio Elixir. Hassabis focused on one extremely ambitious game - Republic: The Revolution, a complex political simulator. Many years ago, at school, Hassabis told his friend Mustafa Suleiman that the world needed a grandiose simulator to simulate its complex dynamics and solve the most complex social problems. Now he tried to do it in the game.

Fit into the game framework was more difficult than he expected. In the end, Elixir released a shortened version of the game to soften the reviews. Other games have failed (including a Bondian villain simulator called Evil Genius). In April 2005, Hassabis closed Elixir. Matthews believes that Hassabis founded the company simply to gain managerial experience. Now Demis needed only one important area of knowledge to begin work on a strong AI. He needed to understand the human brain.

In 2005, Hassabis earned a doctorate in neuroscience at University College London (UCL). He published famous studies of memory and imagination. One of his articles, which has since been quoted more than 1,000 times, has shown that people with amnesia also have difficulty understanding new experiences, suggesting that there is a connection between remembering and creating mental images. Hassabis created a brain representation suitable for the task of creating AGI. Most of the work boiled down to one question: how does the human brain receive and preserve concepts and knowledge?

Hassabis officially founded DeepMind on November 15, 2010. Since then, the company's mission has been unchanged: to "solve intelligence", and then use it to solve everything else. As Hassabis told Singularity Summit participants, this means translating our understanding of how the brain works into software that can use the same self-learning methods.

Hassabis understands that science has not yet fully grasped the essence of the human mind. A strong AI project cannot simply be created on the basis of hundreds of neurobiological studies. But he clearly believes that enough is already known to begin work on strong AI. And yet there is a possibility that his confidence is ahead of reality. We still know very little how the brain actually functions. In 2018, the results of Hassabis's own PhD thesis were called into question by a team of Australian researchers. This is just one article, but it shows that the scientific opinions underlying DeepMind are far from consensus.

The company was co-founded by Mustafa Suleiman and Shane Legge, an obsessed AGI New Zealander whom Hassabis also met at UCL. The company's reputation was growing, and Hassabis was reaping the benefits of his talent. “It's like a magnet,” says Ben Faulkner, a former operations manager at DeepMind. Many employees lived in Europe, far from the HR departments of Silicon Valley giants such as Google and Facebook. Perhaps the main achievement of DeepMind was the hiring of employees immediately after its founding, in order to find and preserve the brightest and best talents in the field of AI. The company opened an office in the attic of a townhouse on Russell Square in Bloomsbury, across the street from UCL.

One of the machine learning methods that the company has focused on has grown out of Hassabis' double passion for games and neuroscience: reinforced learning. Such a program is designed to collect information about the environment, and then study on it, repeatedly reproducing the experience gained, like the activity of the human brain in a dream, as Hassabis told in his lecture on Singularity Summit.

Reinforcement training starts from scratch. The program is shown a virtual environment about which it knows nothing but the rules. For example, a simulation of a game of chess or video games. A program contains at least one component known as a neural network. It consists of layers of computational structures that sift through information to identify specific functions or strategies. Each layer explores the environment at a new level of abstraction. At first, these networks operate with minimal success, but it is important that each failure leaves a mark and is encoded within the network. Gradually, the neural network is becoming more sophisticated, as it is experimenting with different strategies - and receives a reward if successful. If the program moves the chess piece and as a result loses the game, then it will not repeat this error.

The culmination of DeepMind's work was 2016, when the company launched the AlphaGo program, which used reinforcement training along with other methods to play go. To everyone's surprise, in a five-match duel in Seoul, the program beat the world champion. 280 million viewers watched the victory of the car: this event happened a decade earlier than experts predicted. The following year, an improved version of AlphaGo defeated the Chinese go champion.

Like Deep Blue in 1997, AlphaGo has changed the perception of what constitutes human excellence. Board game champions, some of the most brilliant minds on the planet, were no longer considered the pinnacle of intelligence. Almost 20 years after a conversation with the Japanese master Fujuwaraa, Hassabis fulfilled his promise. He later said that he nearly burst into tears during the match. According to tradition, the go student thanks the teacher by defeating him in the match. Hassabis thanked Matthews, defeating the whole game.

DeepBlue won thanks to brute force and computational speed, but AlphaGo's style seemed artistic, almost human. Its grace and sophistication, the superiority of computational muscles seemed to show that DeepMind moved further than its competitors in developing a program that could treat diseases and manage cities.

Hassabis has always said that DeepMind will change the world for the better. But there is no certainty about strong AI. If he ever arises, we do not know whether he will be altruistic or malicious, whether he will submit to human control. Even so, who will take control?

From the very beginning, Hassabis tried to defend the independence of DeepMind. He always insisted that DeepMind stay in London. When Google bought the company in 2014, the issue of control became more relevant. Hassabis was not required to sell the company. He had enough money, and he outlined a business model by which the company develops games to finance research. Google finances had weight, but, like many founders, Hassabis did not want to give up the company that he had grown up. As part of the deal, DeepMind entered into an agreement that would prevent Google from unilaterally taking control of the company's intellectual property. According to an informed person, before the transaction, the parties signed a contract called the Ethics and Safety Review Agreement. Agreement not previously reported

The agreement transfers control of the core technology of a strong AI to DeepMind whenever that AI is created, namely, a steering group called the Ethics Board. According to the same source, the Ethics Council is not some cosmetic concession from Google. He provides DeepMind with solid legal support to maintain control of his most valuable and potentially most dangerous technology. The names of the council members were not made public, but another source close to DeepMind and Google says that it includes all three of the founders of DeepMind (the company refused to answer questions about the agreement, but said that “ethics control from the first days was for us priority ”).

Hassabis can determine the fate of DeepMind in other ways. One of them is staff loyalty. Past and current employees say the Hassabis research program is one of DeepMind's greatest strengths. His program offers a fascinating and important work, free from the pressure of academic circles. Such conditions attracted hundreds of the most talented experts in the world. DeepMind has subsidiaries in Paris and Alberta. Many employees feel closer to Hassabis and his mission than to the revenue-craving parent corporation. As long as Hassabis maintains personal loyalty, he has significant power over his sole shareholder. For Google, it’s better for DeepMind's talents to work for her through an intermediary than they will go to Facebook or Apple.

DeepMind has one more lever, although it requires constant replenishment: favorable advertising. The company is doing well. AlphaGo has become a real PR bomb. Since the acquisition of Google, the company has repeatedly produced miracles that have attracted worldwide attention. One DeepMind program can diagnose eye diseases by scanning the retina. Another learned to play chess from scratch using AlphaGo-style architecture, becoming the greatest chess player of all time in just nine hours of self-study. In December 2018, a program called AlphaFold surpassed its competitors in the task of predicting the three-dimensional structure of proteins using a list of components, potentially paving the way for the treatment of diseases such as Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's.

DeepMind is particularly proud of the developed algorithms that calculate the most effective cooling means of Google data centers, where approximately 2.5 million servers are running. DeepMind said in 2016 that they reduced Google’s energy costs by 40%. But some insiders say this is an exaggerated figure. Google used algorithms to optimize data centers long before DeepMind: “They just want some PR to add value to Alphabet,” says one Google employee. Alphabet's parent company, Google, generously pays DeepMind for such services. So, in 2017, DeepMind billed her for £ 54 million. This figure pales in comparison with DeepMind's current expenses: only $ 200 million was spent on staff that year. In general, DeepMind losses in 2017 amounted to £ 282 million.

These are miserable pennies for the wealthy Internet giant. But other unprofitable companies Alphabet attracted the attention of Ruth Porat, the frugal chief financial officer of Alphabet. For example, the Google Fiber division tried to create a high-speed Internet service provider by running fiber optic lines to private homes. But the project was suspended when it became clear that it would take decades to return the investment. Therefore, it is important for AI researchers to prove their relevance so as not to attract the tenacious look of Mrs. Porat, whose name has already become a household name in Alphabet.

DeepMind's planned achievements in AI are part of a relationship strategy with company owners. DeepMind signals its reputation. This is especially important when Google is accused of invading user privacy and spreading fake news. DeepMind was also lucky to have a supporter at the highest level: Larry Page, one of Google’s two founders, now Alphabet’s CEO. Page is the closest thing Hassabis has to his parent company. Page's father, Carl, studied neural networks in the 60s. At the beginning of his career, Page said he created Google solely to found the AI company.

Tight control over DeepMind, to look good in the eyes of the press, doesn't quite match the academic spirit that pervades the company. Some researchers complain that it is difficult for them to publish their work: they have to overcome several levels of internal censorship before they can at least submit a report for the conference or an article for the journal. DeepMind believes that you need to be careful not to scare the public with the prospect of a strong AI. But too dense silence can ruin the academic atmosphere and weaken the loyalty of employees.

Five years after the acquisition of Google, the question of who controls DeepMind is approaching a critical point. The company’s founders and first employees will soon be able to leave with their financial compensation (shares of Hassabis, probably after the purchase of Google are worth about £ 100 million). But a source close to the company suggests that Alphabet has postponed the monetization of the founders' options by two years. Given his relentless focus on the mission, Hassabis is unlikely to leave the ship. Money interests him only insofar as it helps to achieve the goal of his whole life. But some colleagues have already left. Since the beginning of 2019, three AI engineers have left the company. And Ben Laurie, one of the world's most famous security professionals, has now returned to Google, to his previous employer. This number is small

So far, Google has not intervened in DeepMind. But one recent event raised concern over how long the company will be able to maintain independence.

DeepMind has always planned to use AI to improve healthcare. In February 2016, a new division of DeepMind Health was created, led by Mustafa Suleiman, one of the co-founders. Suleiman, whose mother worked as a nurse at the National Health Service (NHS), hoped to create a program called Streams that would alert doctors when a patient's health worsens. DeepMind had to earn on every effective system operation. Because this work required access to confidential patient information, Suleiman established the Independent Review Panel (IRP), which included representatives from the British healthcare and technology sectors. DeepMind acted very carefully. Subsequently, the British Information Commissioner discovered that one of the partner hospitals violated the law while processing patient data. However, by the end of 2017, Suleiman had signed agreements with four major NHS hospitals.

On November 8, 2018, Google announced the creation of its own division of Google Health. Five days later, they announced that DeepMind Health should be included in the parent unit. Apparently, DeepMind did not warn anyone. According to the documents that we received upon request in accordance with the Law on Freedom of Information, DeepMind notified partner hospitals of this change in only three days. The company declined to report when discussions about the merger began, but said the short gap between the notice and the public announcement was in the interest of transparency. Suleiman wrote in 2016 that "at no stage will patient data ever be associated with or associated with Google accounts, products or services." It seems that his promise was broken. (Answering questions from our publication, DeepMind said that “at this stage, none of our contracts went to Google, and this is possible only with the consent of our partners. The fact that Streams has become a Google service does not mean that patient data ... can be used in other Google products or services. ”)

Google annexation angered DeepMind Health employees. According to people close to this unit, upon completion of the takeover, many employees plan to quit. One of the IRP members, Mike Bracken, has already left. According to several people familiar with the event, Bracken left in December 2017 due to fears that the “control commission” is more of a showcase than a true oversight. When Bracken asked Suleiman whether he would be accountable to the commission and equalize their powers with non-executive directors, Suleiman only grinned. (A spokesman for DeepMind said he “doesn’t remember” about such an incident.) Julian Huppert, the head of the IRP, argues that the group provided “more radical governance” than Brecken expected, as members could speak openly and were not bound by a duty of confidentiality.

This episode reveals that DeepMind's peripheral units are vulnerable to Google. The DeepMind statement said: "We all agreed that it makes sense to combine these efforts in a single joint project with a more powerful resource." The question is whether Google would apply the same logic to DeepMind's work on strong AI.

From the outside it seems that DeepMind has achieved great success. She has already developed software capable of learning to complete tasks on a superhuman level. Hassabis often mentions Breakout, a video game for the Atari console. The Breakout player controls the platform at the bottom of the screen and reflects the ball that bounces off the blocks at the top, collapsing from the hit. The player wins when all the blocks are destroyed. Loses if he misses the ball. Without human instructions, the DeepMind program not only learned how to play the game, but also developed a strategy for launching the ball into the space above the blocks, where it jumps for a long time and earns a bunch of points without effort on the part of the player. According to Hassabis, this demonstrates the power of reinforced learning and the paranormal abilities of DeepMind computer programs.

An impressive demonstration. But Hassabis is missing something. If you move the virtual platform at least a couple of pixels up, the program will fail. The skill acquired by DeepMind is so limited that it cannot even respond to tiny environmental changes that people can take into account - at least not without thousands of extra training rounds. But such changes are an integral part of the surrounding reality. There are no two identical organs of the body for the diagnostician. For a mechanic, no two engines can be configured equally. Therefore, systems trained in the virtual space may experience difficulties when starting in real conditions.

The second catch, which DeepMind rarely talks about, is that success in virtual environments depends on having a reward function: a signal that allows a neural network to measure its progress. The program sees that multiple rebounds from the back wall increase the score. A key part of the development of AlphaGo was the creation of a reward function compatible with such a complex game. Unfortunately, the real world does not offer simple rewards. Progress is rarely measured by individual points. Even if they exist, the task is complicated by political problems. Setting the reward signal to improve the climate (CO₂ concentration in the atmosphere) is contrary to the reward signal for oil companies (stock price) and requires a compromise with many people with conflicting motivations. The reward signals are usually very weak.

DeepMind has found an effective way to learn using a huge amount of computing resources. The AlphaGo program studied for thousands of years of playing time before it understood something. Many AI experts suspect that this method will not work for tasks that offer weaker rewards. DeepMind recognizes the problem. She recently focused on StarCraft 2, a strategic computer game. The decisions made at the beginning of the game have much later consequences, which is closer to the confusing and belated feedback in the real world. In January, DeepMind defeated some of the best players in the world in a demo version, which, although very limited, was still impressive. Her programs also began to study reward functions, taking into account feedback from a human teacher. But involving the teacher,

Current and former researchers at DeepMind and Google, who asked to remain anonymous due to strict non-disclosure agreements, have also expressed skepticism that using such methods, DeepMind can create a strong AI. According to them, the emphasis on high performance in virtual environments makes it difficult to solve the problem with the reward signal. Still, a gaming approach is at the core of DeepMind. The company has an internal leaderboard where programs from competing programming teams compete for virtual domains.

Hassabis has always perceived life as a game. Most of his career is devoted to game development, and most of his free time is spent on gaming practice. At DeepMind, he chose games as his primary means of building strong AI. Like its software, Hassabis can only learn from its own experience. People may forget about the initial task, as DeepMind has already invented some useful medical technologies and excelled the greatest players in the class of board games. These are significant achievements, but not those that the company founder craves. However, he still has a chance to create a strong AI right under Google’s nose, but outside the control of the corporation. If this succeeds, then Demis Hassabis will win the most difficult game.