The Processing of Unrecoverable Errors in Swift

- Tutorial

Preface

This article is an example of how we can do research into Swift Standard Library functions behavior building our knowledge not only on the Library documentation but also on its source code.

Unrecoverable Errors

All events which programmers call "errors" can be separated into two types.

- Events caused by external factors such as a network connection failure.

- Events caused by a programmer's mistake such as reaching a switch operator case which should be unreachable.

The events of the first type are processed in a regular control flow. For example, we react to network failure by showing a message to a user and setting an app to wait for network connection recovery.

We try to find out and eliminate events of the second type as early as possible before the code goes to production. One of the approaches here is to run some runtime checks terminating program execution in a debuggable state and print a message with an indication of where in the code the error has happened.

For example, a programmer may terminate execution if the required initializer was not provided but was called. That will be invariably noticed and fixed during the first test run.

required init?(coder aDecoder: NSCoder) {

fatalError("init(coder:) has not been implemented")

}Another example is the switching between indices (let's assume that for some reason you can't use enumeration).

switch index {

case 0:

// something is done here

case 1:

// other thing is done here

case 2:

// and other thing is done here

default:

assertionFailure("Impossible index")

}Again, a programmer is going to cause crash during debugging here in order to inevitably notice a bug in indexing.

There are five terminating functions from the Swift Standard Library (as for Swift 4.2).

func precondition(_ condition: @autoclosure () -> Bool, _ message: @autoclosure () -> String = default, file: StaticString = #file, line: UInt = #line)func preconditionFailure(_ message: @autoclosure () -> String = default, file: StaticString = #file, line: UInt = #line) -> Neverfunc assert(_ condition: @autoclosure () -> Bool, _ message: @autoclosure () -> String = default, file: StaticString = #file, line: UInt = #line)func assertionFailure(_ message: @autoclosure () -> String = default, file: StaticString = #file, line: UInt = #line)func fatalError(_ message: @autoclosure () -> String = default, file: StaticString = #file, line: UInt = #line) -> NeverWhich of the five terminating functions should we prefer?

Source Code vs Documentation

Let's look at the source code. We can see the following right away:

- Each of these five functions either terminates the program execution or does nothing.

- Possible termination happens in two ways.

- With printing a convenient debug message by calling

_assertionFailure(_:_:file:line:flags:). - Without the debug message just by calling

Builtin.condfail(error._value)orBuiltin.int_trap().

- With printing a convenient debug message by calling

- The difference between the five terminating functions lies in the conditions under which all of the above happens.

fatalError(_:file:line)calls_assertionFailure(_:_:file:line:flags:)unconditionally.- The other four terminating functions evaluate conditions by calling the following configuration evaluation functions. (They begin with an underscore which means that they are internal and are not supposed to be called directly by a programmer who uses Swift Standard Library).

_isReleaseAssertConfiguration()_isDebugAssertConfiguration()_isFastAssertConfiguration()

Now let's look at documentation. We can see the following right away.

fatalError(_:file:line)unconditionally prints a given message and stops execution.- The effects of the other four terminating functions vary depending on the build flag used:

-Onone,-O,-Ounchecked. For example, look atpreconditionFailure(_:file:line:)documentation. - We can set these build flags in Xcode through

SWIFT_OPTIMIZATION_LEVELcompiler build setting. - We also know from Xcode 10 documentation that one more optimization flag —

-Osize— is introduced. - Thus we have the four optimization build flags to consider.

-Onone(don't optimize)-O(optimize for speed)-Osize(optimize for size)-Ounchecked(switch off many compiler checks)

We may conclude that the configuration evaluated in the four terminating functions is set by these build flags.

Running Configuration Evaluation Functions

Although configuration evaluation functions are designed for internal usage, some of them are public for testing purposes, and we may try them through CLI giving the following commands in Bash.

$ echo 'print(_isFastAssertConfiguration())' >conf.swift

$ swift conf.swift

false

$ swift -Onone conf.swift

false

$ swift -O conf.swift

false

$ swift -Osize conf.swift

false

$ swift -Ounchecked conf.swift

true$ echo 'print(_isDebugAssertConfiguration())' >conf.swift

$ swift conf.swift

true

$ swift -Onone conf.swift

true

$ swift -O conf.swift

false

$ swift -Osize conf.swift

false

$ swift -Ounchecked conf.swift

falseThese tests and source code inspection lead us to the following rough conclusions.

There are three mutually exclusive configurations.

- Release configuration is set by providing either a

-Oor a-Osizebuild flag. - Debug configuration is set by providing either a

-Ononebuild flag or no optimization flags at all. _isFastAssertConfiguration()is evaluated totrueif a-Ouncheckedbuild flag is set. Although this function has a word "fast" in its name, it has nothing to do with optimizing for speed-Obuild flag.

NB: These conclusions are not the strict definition of when debug builds or release builds take place. It's a more complex issue. But these conclusions are correct for the context of terminating functions usage.

Simplifying The Picture

-Ounchecked

Let's look not at what the -Ounchecked flag is for (it's irrelevant here) but at what its role is in the context of terminating functions usage.

- Documentation for

precondition(_:_:file:line:)andassert(_:_:file:line:)says, "In-Ouncheckedbuilds, condition is not evaluated, but the optimizer may assume that it always evaluates to true. Failure to satisfy that assumption is a serious programming error." - Documentation for

preconditionFailure(_:file:line)andassertionFailure(_:file:line:)says, "In-Ouncheckedbuilds, the optimizer may assume that this function is never called. Failure to satisfy that assumption is a serious programming error." - We can see from the source code that evaluation of

_isFastAssertConfiguration()totrueshould not happen. (If it does happen, strange_conditionallyUnreachable()is called. See see lines 136 and 176.)

Speaking more directly, you must not allow reachability of the following four terminating functions with the -Ounchecked build flag set for your program.

precondition(_:_:file:line:)preconditionFailure(_:file:line)assert(_:_:file:line:)assertionFailure(_:file:line:)

Use only fatalError(_:file:line) while applying -Ounchecked and at the same time allowing that the point of your program with fatalError(_:file:line) instruction may be reachable.

The Role of a Condition Check

Two of the terminating functions let us check for conditions. The source code inspection allow us to see that if condition is failed then function behavior is the same as the behavior of its respective cousin:

precondition(_:_:file:line:)becomespreconditionFailure(_:file:line),assert(_:_:file:line:)becomesassertionFailure(_:file:line:).

That knowledge makes further analysis easier.

Release vs Debug Configurations

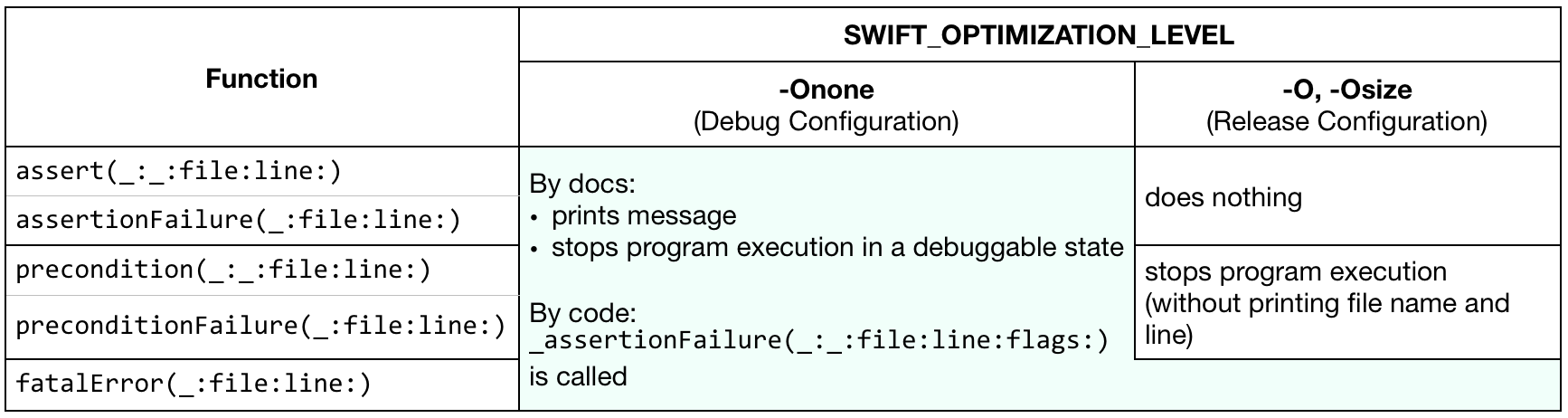

Eventually, further documentation and source code inspection allows us to formulate the following table.

It is clear now that the most important choice for a programmer is what program behavior should be like in release if a runtime check reveals an error.

The key takeaway here is that assert(_:_:file:line:) and assertionFailure(_:file:line:) make the impact of program failure less severe. For example, an iOS app may have corrupted UI (since some important runtime checks were failed) but it won't crash.

But that scenario may not be the one you wanted. You have a choice.

Never Return Type

Never is used as a return type of function that unconditionally throws an error, traps, or otherwise do not terminate normally. Those kinds of functions do not actually return, they never return.

Among the five terminating functions, only preconditionFailure(_:file:line) and fatalError(_:file:line) return Never because only these two functions unconditionally stop program executions and therefore never return.

Here is a nice example of utilizing Never type in a command line app. (Although this example doesn’t use Swift Standard Library terminating functions but standard C exit() function instead).

func printUsagePromptAndExit() -> Never {

print("Usage: command directory")

exit(1)

}

guard CommandLine.argc == 2 else {

printUsagePromptAndExit()

}

// ...If printUsagePromptAndExit() returns Void instead of Never, you get a buildtime error with the message, "'guard' body must not fall through, consider using a 'return' or 'throw' to exit the scope". By using Never you are saying in advance that you never exit the scope and therefore compiler won't give you a buildtime error. Otherwise, you should add return at the end of the guard code block, which doesn't look nice.

Takeaways

- It doesn't matter which terminating function to use if you are sure that all your runtime checks are relevant only for the Debug configuration.

- Use only

fatalError(_:file:line)while applying-Ouncheckedand at the same time allowing that the point of your program withfatalError(_:file:line)instruction may be reachable. - Use

assert(_:_:file:line:)andassertionFailure(_:file:line:)if you are worried that runtime checks may fail somehow in release. At least your app won't crash. - Use

Neverto make your code look neat.

Useful Links

- WWDC video "What's New in Swift" telling about

SWIFT_OPTIMIZATION_LEVELbuild setting (from 11 minute). - How Never Works Internally in Swift

NSHipster's article about nature of Never- Swift Forums discussion about suggestion to deprecate

-Ounchecked.