Rust in detail: writing a scalable chat from scratch, part 1

- Transfer

Part 1: We implement WebSocket. Introduction

In this series of articles, we will look at the process of creating a scalable chat that will work in real time.

The purpose of this review is to step-by-step study the basics of the rapidly gaining popularity of the Rust programming language in practice, with the simultaneous coverage of system interfaces.

In the first part, we will consider the initial setup of the environment and the implementation of the simplest WebSocket server. To understand the technical details of the article, you will not need experience with the Rust language, although knowledge of the basics of system APIs (POSIX) and C / C ++ will not be superfluous. Before you start reading, take a little time (and coffee) - the article describes everything as detailed as possible and therefore quite long.

1 Rust - the reason for choosing

I became interested in the Rust programming language because of my long-standing passion for system programming, which, although entertaining, is also very complicated - all because there are a lot of completely unobvious moments and tricky problems waiting for beginners and experienced developers.

And, perhaps, the most difficult problem here can be called safe work with memory. It is incorrect working with memory that causes many bugs: buffer overflows , memory leaks , double memory deallocation, dangling links , dereferencing pointers to already freed memory, etc. And such errors sometimes entail serious security problems - for example, the cause of the notorious bug in OpenSSL, Heartbleed, is nothing more than sloppy handling of memory. And this is just the tip of the iceberg - no one knows how many such gaps are hidden in the software that we use every day.

And, perhaps, the most difficult problem here can be called safe work with memory. It is incorrect working with memory that causes many bugs: buffer overflows , memory leaks , double memory deallocation, dangling links , dereferencing pointers to already freed memory, etc. And such errors sometimes entail serious security problems - for example, the cause of the notorious bug in OpenSSL, Heartbleed, is nothing more than sloppy handling of memory. And this is just the tip of the iceberg - no one knows how many such gaps are hidden in the software that we use every day. In C ++, several ways to solve such problems were invented - for example, the use of smart pointers [1] or allocation on the stack [2] . Unfortunately, even using such approaches, there is still the possibility of “shooting your own leg” —that goes beyond the boundaries of the buffer or use low-level functions for working with memory that always remain available.

That is, at the language level there is no prerequisite to apply such practices - instead, it is believed that “good developers” always use them themselves and never make mistakes. However, I believe that the existence of such critical problems in the code is in no way connected with the level of developers, because people cannot thoroughly manually check large amounts of code - this is the task of the computer. To some extent, static analysis tools help here - but, again, not all and not always use them.

It is for this reason that there is another fundamental method to get rid of problems in working with memory: garbage collection is a separate complex field of knowledge in computer science. Almost all modern languages and virtual machines have some form of automatic garbage collection, and despite the fact that in most cases this is a pretty good solution, it has its drawbacks: firstly, automatic garbage collectors are difficult to understand and implement [3 ] . Secondly, the use of garbage collection implies a pause to free up unused memory [4] , which usually entails the need for fine tuning to reduce latency in highly loaded applications.

The Rust language has a different approach to the problem - you can say the golden mean is the automatic release of memory and resources without additional memory or processor time and without the need for self-tracking of each step. This is achieved through the application of the concepts of ownership and borrowing .

The language is based on the statement that each value can have only one owner - that is, there can only be one mutable variable pointing to a specific area of memory:

let foo = vec![1, 2, 3];

// Мы создаем новый вектор (массив), содержащий элеметы 1, 2, и 3,

// и привязываем его к локальной переменной `foo`.

let bar = foo;

// Передаем владение объектом переменной `bar`.

// После этого мы не можем получить доступ к переменной `foo`,

// поскольку она теперь ничем не "владеет" - т.е., не имеет никакой привязки.

This approach has interesting consequences: since the value is associated exclusively with one variable, the resources associated with this value (memory, file descriptors, sockets, etc.) are automatically freed when the variable leaves the scope (which is set by code blocks inside curly brackets ,

{and }). Such artificial restrictions may seem unnecessary and overly complicated, but if you think carefully, then, by and large, this is the “killer feature” of Rust, which appeared solely for practical reasons. It is this approach that allows Rust to look like a high-level language while maintaining the effectiveness of low-level code written in C / C ++.

However, despite all its interesting features, until recently Rust had its own serious flaws - for example, a very unstable API, in which no one could guarantee compatibility. But the creators of the language have come a long way in almost a decade [5] , and now, with the release of stable version 1.0, the language has evolved to the point where it can begin to be put into practice in real projects.

2 Goals

I prefer to learn new languages and concepts while developing relatively simple projects using them in the real world. Thus, the possibilities of the language are studied exactly when they become necessary. As a project for exploring Rust, I chose an anonymous chat service like Chat Roulette and many others. In my opinion, this is a suitable choice for the reason that chats are usually demanding for low response time from the server and imply the presence of a large number of simultaneous connections. We will count on several thousand - so we can look at the memory consumption and performance of programs written in Rust in a real environment.

The end result should be a binary program file with scripts to deploy our server to various cloud hosting services.

But before we start writing code, we need to make a small digression to explain some points with I / O, since proper work with it is a key point in the development of network services.

3 I / O Options

To complete the tasks, our service needs to send and receive data through network sockets.

At first glance, the task is simple, but in fact there are many possible ways to solve it of varying complexity and varying effectiveness. The main difference between them lies in the approach to locks : the standard practice here is to stop the processor while waiting for new data to come into the socket.

Since we cannot build a service for one user who will block the others, we must isolate them somehow from each other. A typical solution is to create a separate thread for each user. Thus, not the whole process will be blocked, but only one of its threads. The disadvantage of this approach, despite its relative simplicity, is increased memory consumption - each thread, when created, reserves some of the memory for the stack [6] . In addition, the matter is complicated by the need for context switchingexecution - in modern server processors there are usually from 8 to 16 cores, and if we create more threads than hardware allows, the OS scheduler stops coping with task switching at a sufficient speed.

Therefore, scaling a multi-threaded program to a large number of connections can be quite difficult, and in our case it is hardly reasonable at all - because we are planning several thousand simultaneously connected users. In the end, you have to be prepared for the Habraeffect!

4 Event loop

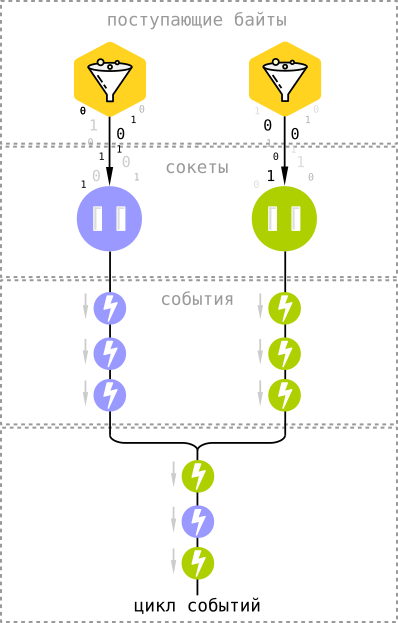

To work effectively with I / O, we will use multiplexing system APIs, which are based on an event processing loop . In the Linux kernel for this is the mechanism the epoll [7] , and in the X and FreeBSD OS - kqueue [8] .

To work effectively with I / O, we will use multiplexing system APIs, which are based on an event processing loop . In the Linux kernel for this is the mechanism the epoll [7] , and in the X and FreeBSD OS - kqueue [8] . Both of these APIs are arranged in a rather similar way, and the general idea is simple: instead of waiting for new data to come to the sockets through the network, we ask the sockets to notify us of the bytes that arrived. Event

Alertsenter the general cycle, which in this case acts as a blocker. That is, instead of constantly checking thousands of sockets for new data in them, we just wait for the sockets to tell us about it - and the difference is quite significant, since quite often connected users are in standby mode, sending nothing and not receiving. This is especially true for applications using WebSocket. In addition, using asynchronous I / O, we have practically no overhead - all that needs to be stored in memory is the socket file descriptor and client state (in the case of chat, this is several hundred bytes per connection).

A curious feature of this approach is the ability to use asynchronous I / O not only for network connections, but also, for example, to read files from disk - the event loop accepts any type of file descriptors (and sockets in the * NIX world are exactly that).

The event loop in Node.js and the EventMachine gem in Ruby work in exactly the same way.

The same is true in the case of the nginx web server, which uses exclusively asynchronous I / O [9] .

5 Getting Started

Further text implies that you already have Rust installed. If not yet, then follow the documentation on the official website .

There is a program in Rust’s standard package called

cargothat performs functions similar to Maven, Composer, npm, or rake - it manages the dependencies of our application, builds a project, runs tests, and most importantly, simplifies the process of creating a new project. This is exactly what we need at the moment, so let's try to open a terminal and type this command:

cargo new chat --bin

The argument

--bintells Cargo to create a startup application, not a library. As a result, we will have two files:

Cargo.toml

src/main.rs

Cargo.tomlcontains a description and links to project dependencies (similar to package.jsonin JavaScript). src/main.rs- the main source file and the entry point to our program. We don’t need anything else to start with, so you can try to compile and run the program with one command -

cargo run. The same command displays errors in the code, if any.If you are a happy Emacs user, you will be happy to know that he is compatible with Cargo “out of the box” - just install the packagerust-modefrom the MELPA repository and configure the compile command to startcargo build.

6 Event Handling in Rust

We pass from theory to practice. Let's try to run the simplest event loop that will wait for new messages to appear. To do this, we do not need to manually connect the various system APIs - just use the existing library for working with asynchronous I / O called “ Metal IO ” or mio .

As you remember, the Cargo program deals with dependencies. It downloads libraries from the crates.io repository , but in addition it allows you to get them from Git repositories directly - this feature is useful in cases where we need to use the latest version of the library that has not yet been loaded into the package repository.

At the time of writing,

mioonly the outdated version 0.3 is available in the repository - in the development version 0.4 there are many useful changes, moreover, incompatible with older versions. Therefore, we will connect it directly through GitHub, adding such lines to Cargo.toml:[dependencies.mio]

git = "https://github.com/carllerche/mio"

After we have defined the dependency in the project description, add the import to

main.rs:extern crate mio;

use mio::*;

Use is

mioquite simple. First of all, let's create an event loop by calling a function EventLoop::new(). An empty loop, however, is of no use, so let's immediately add event handling to it for our chat, defining a structure with functions that will correspond to the interface Handler. Although Rust does not support “traditional” object-oriented programming, the structures are largely similar to classes, and they can implement interfaces that are regulated in the language through traits in a manner similar to the classical OOP .

Let's define a new structure:

struct WebSocketServer;

And we realize the type

Handlerfor her:impl Handler for WebSocketServer {

// У типажей может существовать стандартная реализация для их функций, поэтому

// интерфейс Handler подразумевает описание только двух свойств: указания

// конкретных типов для таймаутов и сообщений.

// В ближайшее время мы не будем описывать все эти детали, поэтому давайте просто

// скопируем типовые значения из примеров mio:

type Timeout = usize;

type Message = ();

}

Now run the event loop:

fn main() {

let mut event_loop = EventLoop::new().unwrap();

// Создадим новый экземпляр структуры Handler:

let mut handler = WebSocketServer;

// ... и предоставим циклу событий изменяемую ссылку на него:

event_loop.run(&mut handler).unwrap();

}

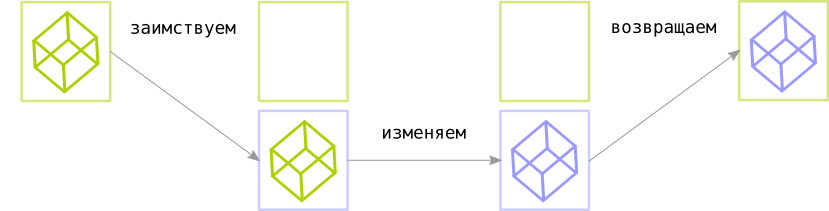

Here we first encounter the use of borrowing (borrows) : pay attention to

&mutthe last line. This means that we temporarily transfer the “ownership” of the value, linking it to another variable with the possibility of mutation of the data.

Simply put, you can imagine the principle of borrowing as follows (pseudocode):

// Связываем значение с его "владельцем" - переменной owner:

let mut owner = value;

// Создаем новую область видимости и заимствуем значение у его владельца:

{

let mut borrow = owner;

// Теперь у владельца нет доступа к его значению.

// Но заимствующая переменная может его читать и изменять:

borrow.mutate();

// Теперь мы можем вернуть измененное значение владельцу:

owner = borrow;

}

The above code is equivalent to this:

// Связываем значение с его "владельцем" - переменной owner:

let owner = value;

{

// Заимствуем значение у его владельца:

let mut borrow = &mut owner;

// Теперь владелец может читать значение, но не может изменять его.

// А вот заимствующая переменная имеет полный доступ:

borrow.mutate();

// Все значения автоматически возвращаются их владельцам при выходе

// заимствующих переменных из области видимости.

}

For each scope , a variable can have only one mutable borrow , and even the owner of the value cannot read or change it until the borrowing leaves the scope.

In addition, there is an easier way to borrow values through immutable borrow , which allows you to use a read-only value. And, unlike

&mut, a variable borrowing, it does not set any limits for reading, only for writing - as long as there are unchanged borrowings in the scope, the value cannot be changed and borrowed through &mut.It's okay if such a description seemed not clear enough to you - sooner or later an intuitive understanding will come, since borrowing in Rust is used everywhere, and as you read through the article you will find more practical examples.

Now let's get back to our project. Run the “

cargo run” command and Cargo will download all the necessary dependencies, compile the program (with some warnings, which we can ignore for now), and run it. As a result, we will see a terminal window with a blinking cursor. Not a very interesting result, but at least it shows that the program runs correctly - we have successfully launched the event loop, although it does not do anything useful so far. Let's fix this state of affairs.

To interrupt a program, use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl + C.

7 TCP server

To start the TCP server, which will accept connections through the WebSocket protocol, we will use the structure (struct) intended for this -

TcpListenerfrom the package mio::tcp. The process of creating a server TCP socket is fairly straightforward - we bind to a specific address (IP + port number), listen to the socket and accept connections. We will not leave him much. Take a look at the code:

use mio::tcp::*;

use std::net::SocketAddr;

...

let address = "0.0.0.0:10000".parse::().unwrap();

let server_socket = TcpListener::bind(&address).unwrap();

event_loop.register(&server_socket,

Token(0),

EventSet::readable(),

PollOpt::edge()).unwrap();

Let's look at it line by line.

First of all, we need to import into the scope of our module a

main.rspacket for working with TCP and a structure SocketAddrthat describes the socket address - add these lines to the top of the file:use mio::tcp::*;

use std::net::SocketAddr;

Let's parse the string

"0.0.0.0:10000"into the structure that describes the address and bind the socket to this address:let address = "0.0.0.0:10000".parse::().unwrap();

server_socket.bind(&address).unwrap();

Pay attention to how the compiler displays the necessary type of structure for us: since it

server_socket.bindexpects a type argument SockAddr, we do not need to specify it explicitly and clog the code - the Rust compiler is able to independently determine it. Create a listening socket and start listening:

let server_socket = TcpListener::bind(&address).unwrap();

You may also notice that we almost everywhere invoke the

unwrapresult of the function execution - this is a pattern of error handling in Rust, and we will return to this topic soon. Now let's add the created socket to the event loop:

event_loop.register(&server_socket,

Token(0),

EventSet::readable(),

PollOpt::edge()).unwrap();

The call is

registermore complicated - the function takes the following arguments:- Token is a unique socket identifier. When an event falls into a loop, we need to somehow understand which socket it belongs to - in this case, the token serves as a link between the sockets and the events they generate. In the above example, we associate the token

Token(0)with a server socket waiting for connection. - EventSet describes what events we subscribe to: the arrival of new data to the socket, the availability of the socket for recording, or both.

EventSet::readable()in the case of a server socket, it subscribes us to only one event - the establishment of a connection with a new client. - PollOpt sets event subscription settings.

PollOpt::edge()means that events are triggered on the edge (edge-triggered) , and not on the level (level-triggered) .

The difference between the two approaches, the names of which are borrowed from electronics, lies in the moment when the socket notifies us of an event that has occurred - for example, when a datareadable()event occurs (i.e., if we are subscribed to an event ) in case of a level response, we receive an alert if there is readable data in the socket buffer. In the case of a signal along the edge, we will receive an alert at the moment when new data arrives at the socket- i.e., if during the processing of the event we did not read the entire contents of the buffer, then we will not receive new alerts until new data arrives. A more detailed description (in English) is in the answer to Stack Overflow .

Now compile the resulting code and run the program using the command

cargo run. In the terminal, we still will not see anything except the blinking cursor - but if we execute the command separately netstat, we will see that our socket is waiting for connections to the port number 10000:$ netstat -ln | grep 10000 tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:10000 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN

8 Accept connections

All WebSocket connections begin with a confirmation of the establishment of a connection (the so-called handshake ), a special sequence of requests and responses transmitted over HTTP. This means that before proceeding with the implementation of WebSocket, we must teach our server how to communicate using the basic protocol, HTTP / 1.1.

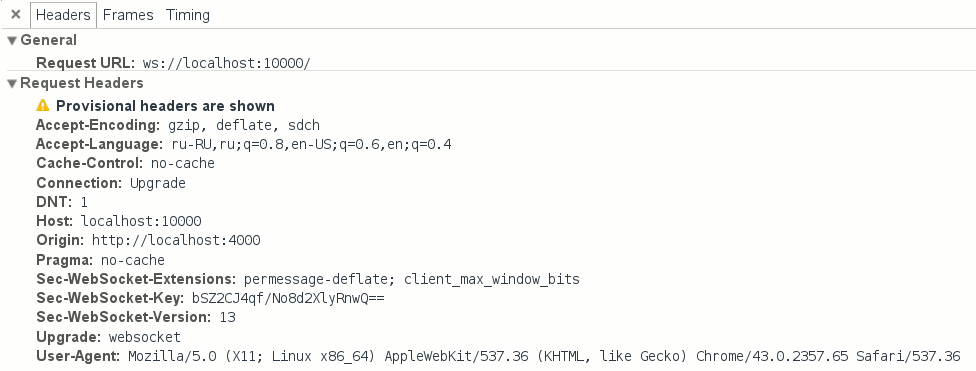

But we need only a small part of HTTP: a client who wants to establish a connection through WebSocket sends a request with headers

Connection: Upgradeand Upgrade: websocket, and we must respond to this request in a certain way. And that’s all - we don’t need to write a full-fledged web server with the distribution of files, static content, etc. - there are more advanced and suitable tools for this (for example, the same nginx).

WebSocket connection request headers.

But before we start implementing HTTP, we need to write code to establish connections with clients and to subscribe to events coming from them.

Consider the basic implementation:

use std::collections::HashMap;

struct WebSocketServer {

socket: TcpListener,

clients: HashMap,

token_counter: usize

}

const SERVER_TOKEN: Token = Token(0);

impl Handler for WebSocketServer {

type Timeout = usize;

type Message = ();

fn ready(&mut self, event_loop: &mut EventLoop,

token: Token, events: EventSet)

{

match token {

SERVER_TOKEN => {

let client_socket = match self.socket.accept() {

Err(e) => {

println!("Ошибка установления подключения: {}", e);

return;

},

Ok(None) => panic!("Вызов accept вернул 'None'"),

Ok(Some(sock)) => sock

};

self.token_counter += 1;

let new_token = Token(self.token_counter);

self.clients.insert(new_token, client_socket);

event_loop.register(&self.clients[&new_token],

new_token, EventSet::readable(),

PollOpt::edge() | PollOpt::oneshot()).unwrap();

}

}

}

}

There was a lot of code, so let's look at it in more detail - step by step.

First of all, we need to add state to the server structure

WebSocketServer- it will store the server socket and sockets of connected clients.use std::collections::HashMap;

struct WebSocketServer {

socket: TcpListener,

clients: HashMap,

token_counter: usize

}

To store client sockets, we use the data structure

HashMapfrom the standard collection library std::collections- this is the standard implementation for hash tables (also known as dictionaries and associative arrays). As a key, we will use tokens already familiar to us, which should be unique for each connection. To begin with, we can generate tokens in a simple way - using a counter, which we will increase by one for each new connection. For this, we need a variable in the structure

token_counter. Next, we again come in handy type

Handlerfrom the library mio:impl Handler for WebSocketServer

In the implementation of the type, we need to redefine the callback function (callback) -

ready. Redefinition means that the type Handleralready contains a dummy function readyand blanks for some other callback functions. The implementation defined in the type does not, of course, do anything useful, so we need to define our own version of the function to handle the events of interest to us:fn ready(&mut self, event_loop: &mut EventLoop,

token: Token, events: EventSet)

This function will be called every time the socket becomes available for reading or writing (depending on the subscription), and through its call parameters we get all the necessary information: an instance of the structure of the event loop, the token associated with the event source (in this case, with socket), and a special structure

EventSetthat contains a set of flags with information about the event ( readable in the case of a notification about the availability of the socket for reading, or writable , respectively, for writing). The listening socket generates readable eventsThe moment a new client enters the queue of pending connections. But before we start connecting, we need to make sure that the source of the event is the listening socket. We can easily verify this using pattern matching :

match token {

SERVER_TOKEN => {

...

}

}

What does it mean? The syntax is

matchreminiscent of the standard switch construct of “traditional” imperative programming languages, but provides much more features. For example, in Java, a construct is switchlimited to a specific set of types and works only for enum numbers, strings, and enumerations. In Rust, however, matchit allows you to make comparisons for almost any type, including multiple values, structures, etc. In addition to matching, it matchalso allows you to capture the contents or parts of samples in a manner similar to regular expressions. In the above example, we map the token to the sample

Token(0)- as you recall, it is connected to the listening socket. And to make our intentions more clear when reading the code, we defined this token in the formconstantsSERVER_TOKEN :const SERVER_TOKEN: Token = Token(0);

Thus, the example of expression

matchin this case is equivalent to this: match { Token(0) => ... }. Now that we are confident that we are dealing with a server socket, we can establish a connection with the client:

let client_socket = match self.socket.accept() {

Err(e) => {

println!("Ошибка установления соединения: {}", e);

return;

},

Ok(None) => unreachable!(),

Ok(Some(sock)) => sock

};

Here we again make a comparison with the sample, this time checking the result of executing a function

accept()that returns the client socket in a “wrapper” of type . this is a special type that is fundamental to error handling in Rust - it is a wrapper over “undefined” results, such as errors, timeouts (timeouts), etc.

In each individual case, we can independently decide what to do with such results, but correctly process all the errors, although, of course, and correctly, but quite tediously. Here we come to the rescue of a function we already know that provides standard behavior: interrupting program execution in the event of an error, and “unpacking” the result of the function from the containerResult> Resultunwrap()Resultin the event that everything is in order. Thus, using unwrap(), we mean that we are interested only in the immediate result, and the situation with the program stopping its execution if we are satisfied with the error. This is acceptable behavior at some points, however, in the case of

accept()it would be unreasonable to use it unwrap(), since in case of an unsuccessful combination of circumstances, its call could turn into a shutdown of our server and disconnect all users. Therefore, we simply output the error to the log and continue execution:Err(e) => {

println!("Ошибка установления соединения: {}", e);

return;

},

A type

Optionis like a Result“wrapper” that determines the presence or absence of a value. The absence of a value is denoted as None; in the opposite case, the value takes the form Some(value). As you probably guess, this type is comparable to null or None types in other languages, it is only Optionsafer due to the fact that all null values are localized and (like Result) require mandatory “unpacking” before use - so you will never see “Famous” mistake NullReferenceException, if you yourself do not want to. So let's unpack the returned

accept()result:Ok(None) => unreachable!(),

In this case, the situation where a value

Noneis returned as a result is impossible — accept()it will be returned only if we try to call this function when applied to a client (i.e., not listening) socket. And since we are confident that we are dealing with a server socket, we should not get to the execution of this piece of code in a normal situation - therefore, we use a special construction unreachable!()that interrupts program execution with an error. We continue to compare the results with the samples:

let client_socket = match self.socket.accept() {

...

Ok(Some(sock)) => sock

}

Here the most interesting thing: since it

matchis not just an instruction, but an expression (that is, it matchalso returns the result), in addition to matching, it also allows you to capture values. Thus, we can use it to assign results to variables - which we do above by unpacking the value from the type and assigning it to a variable .

We save the received socket in a hash table, not forgetting to increase the token counter:Result> client_socketlet new_token = Token(self.token_counter);

self.clients.insert(new_token, client_socket);

self.token_counter += 1;

Finally, we need to subscribe to events from the socket with which we just established a connection - let's register it in the event loop. This is done in exactly the same way as with the registration of the server socket, only now we will provide another token as parameters, and, of course, a different socket:

event_loop.register(&self.clients[&new_token],

new_token, EventSet::readable(),

PollOpt::edge() | PollOpt::oneshot()).unwrap();

You may have noticed another difference in the set of arguments: in addition to

PollOpt::edge(), we have added a new option PollOpt::oneshot(). It instructs to temporarily remove the registration of the socket from the loop when any event is triggered, which is useful to simplify the server code. Without this option, we would have to manually monitor the current state of the socket - is it possible to write now, is it possible to read now, etc. Instead, we will simply register the socket again each time, with the set of options and subscriptions we need at the moment. On top of that, this approach is useful for multi-threaded event loops, but more on that next time. And finally, due to the fact that our structure

WebSocketServercomplicated, we need to change the server registration code in the event loop. The changes are quite simple and mainly concern the initialization of the new structure:let mut server = WebSocketServer {

token_counter: 1, // Начинаем отсчет токенов с 1

clients: HashMap::new(), // Создаем пустую хеш-таблицу, HashMap

socket: server_socket // Передаем владение серверным сокетом в структуру

};

event_loop.register(&server.socket,

SERVER_TOKEN,

EventSet::readable(),

PollOpt::edge()).unwrap();

event_loop.run(&mut server).unwrap();

9 Parsim HTTP

Now that we have established a connection with the client, according to the protocol, we need to parse the incoming HTTP request and “switch” ( upgrade ) the connection to the WebSocket protocol.

Since this is a rather boring task, we won’t do it all manually - instead, we’ll use the

http-muncherHTTP parsing library to add it to the dependency list. The library adapts for HTTP the HTTP parser from Node.js (it is also a parser in nginx), which allows you to process requests in streaming mode, which will be very useful for TCP connections. Let's add a dependency to

Cargo.toml:[dependencies]

http-muncher = "0.2.0"

We will not consider the library API in detail, and immediately proceed to writing the parser:

extern crate http_muncher;

use http_muncher::{Parser, ParserHandler};

struct HttpParser;

impl ParserHandler for HttpParser { }

struct WebSocketClient {

socket: TcpStream,

http_parser: Parser

}

impl WebSocketClient {

fn read(&mut self) {

loop {

let mut buf = [0; 2048];

match self.socket.try_read(&mut buf) {

Err(e) => {

println!("Ошибка чтения сокета: {:?}", e);

return

},

Ok(None) =>

// В буфере сокета больше ничего нет.

break,

Ok(Some(len)) => {

self.http_parser.parse(&buf[0..len]);

if self.http_parser.is_upgrade() {

// ...

break;

}

}

}

}

}

fn new(socket: TcpStream) -> WebSocketClient {

WebSocketClient {

socket: socket,

http_parser: Parser::request(HttpParser)

}

}

}

And yet we need to make some changes to the implementation of the function

readyin the structure WebSocketServer:match token {

SERVER_TOKEN => {

...

self.clients.insert(new_token, WebSocketClient::new(client_socket));

event_loop.register(&self.clients[&new_token].socket, new_token, EventSet::readable(),

PollOpt::edge() | PollOpt::oneshot()).unwrap();

...

},

token => {

let mut client = self.clients.get_mut(&token).unwrap();

client.read();

event_loop.reregister(&client.socket, token, EventSet::readable(),

PollOpt::edge() | PollOpt::oneshot()).unwrap();

}

}

Let's try to review the new code line by line again.

First of all, we import the library and add a controlling structure for the parser:

extern crate http_muncher;

use http_muncher::{Parser, ParserHandler};

struct HttpParser;

impl ParserHandler for HttpParser { }

Here we add a trait implementation

ParserHandlerthat contains some useful callback functions (the same as Handlerfrom miothe case of the structure WebSocketServer). These callbacks are called immediately as soon as the parser has any useful information - HTTP headers, request contents, etc. But now we only need to find out if the client sent a set of special headers to switch the HTTP connection to the WebSocket protocol. The parser structure already has the necessary functions for this, so we will not redefine callbacks for now, leaving their standard implementations. However, there is one detail: the HTTP parser has its own state, which means that we will need to create a new instance of the structure

HttpParserfor every new customer. Given that each client will store the state of the parser, let's create a new structure that describes an individual client:struct WebSocketClient {

socket: TcpStream,

http_parser: Parser

}

Since now we can store the client socket in the same place, we can replace the definition with in the server structure. In addition, it would be convenient to move the code that relates to the processing of clients into the same structure - if you keep everything in one function , then the code will quickly turn into a “noodle”. So let's add a separate implementation in the structure :

HashMapHashMapreadyreadWebSocketClientimpl WebSocketClient {

fn read(&mut self) {

...

}

}

This function does not need to accept any parameters - we already have the necessary state outside the structure itself.

Now we can start reading the data coming from the client:

loop {

let mut buf = [0; 2048];

match self.socket.try_read(&mut buf) {

...

}

}

What's going on here? We begin an endless cycle (construction

loop { ... }), allocate 2 KB of memory for the buffer where we will write data, and try to write incoming data into it. The call

try_readmay result in an error, so we carry out a pattern matching by type Result:match self.socket.try_read(&mut buf) {

Err(e) => {

println!("Ошибка чтения сокета: {:?}", e);

return

},

...

}

Then we check if there are more bytes left for reading in the TCP socket buffer:

match self.socket.try_read(&mut buf) {

...

Ok(None) =>

// В буфере сокета больше ничего нет.

break,

...

}

try_readreturns the result Ok(None)if we have read all the available data received from the client. When this happens, we break the endless cycle and continue to wait for new events. And finally, here is the handling of the case when the call

try_readwrote data to our buffer:match self.socket.try_read(&mut buf) {

...

Ok(Some(len)) => {

self.http_parser.parse(&buf[0..len]);

if self.http_parser.is_upgrade() {

// ...

break;

}

}

}

Here we send the received data to the parser and immediately check the available HTTP headers for a request to “switch” the connection to WebSocket mode (more precisely, we are expecting a header

Connection: Upgrade). The last improvement is the function

newthat we need in order to make it more convenient to create instances of the client structure WebSocketClient:fn new(socket: TcpStream) -> WebSocketClient {

WebSocketClient {

socket: socket,

http_parser: Parser::request(HttpParser)

}

}

This is the so-called associated function , which in many respects is similar to the static methods from the traditional object-oriented approach, and specifically

newwe can compare the function with the constructor. Here we just create an instance WebSocketClient, but it should be understood that we can do it the same way without the “constructor” function - it is rather a matter of convenience, because without the use of constructor functions, the code can become often repeated, without any special need. In the end, the DRY principle (“don't repeat”) was invented for a reason. There are a couple more details. Please note that we do not use the keyword

returnExplicitly - Rust allows you to automatically return the last expression of a function as its result. And this line needs clarification:

http_parser: Parser::request(HttpParser)

Here we create a new instance of the structure

Parserusing an associative function Parser::request. As an argument, we pass the created instance of the previously defined structure HttpParser. Now that we have sorted out the clients, we can return to the server code, in which

readywe make the following changes in the handler :match token {

SERVER_TOKEN => { ... },

token => {

let mut client = self.clients.get_mut(&token).unwrap();

client.read();

event_loop.reregister(&client.socket, token, EventSet::readable(),

PollOpt::edge() | PollOpt::oneshot()).unwrap();

}

}

We have added a new condition in

matchthat processes all other tokens, in addition to SERVER_TOKEN- that is, events in client sockets. With the existing token, we can borrow a mutable link to the corresponding instance of the client structure from the hash table:let mut client = self.clients.get_mut(&token).unwrap();

Now let's call the function for this client

readthat we defined above:client.read();

In the end, we have to re-register the client in the event loop (because of

oneshot()):event_loop.reregister(&client.socket, token, EventSet::readable(),

PollOpt::edge() | PollOpt::oneshot()).unwrap();

As you can see, the differences from the client socket registration procedure are insignificant - in fact, we simply change the name of the called function from

registerto reregister, passing all the same parameters. That's all - now we know when the client wants to establish a connection using the WebSocket protocol, and now we can think about how to respond to such requests.

10 Connection Confirmation

Essentially, we could send back such a simple set of headers:

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols

Connection: Upgrade

Upgrade: websocket

If not for one important detail: the WebSocket protocol also obliges us to send a properly composed header

Sec-WebSocket-Accept. According to the RFC , you need to do this following certain rules - we need to get and remember the header sent by the client Sec-WebSocket-Key, add a certain static string ( "258EAFA5-E914-47DA-95CA-C5AB0DC85B11") to it, then hash the result with the SHA-1 algorithm, and finally encode it all in base64. There are no functions for working with SHA-1 and base64 in the Rust standard library, but all the necessary libraries are in the crates.io repository , so let's add them to ours

Cargo.toml:[dependencies]

...

rustc-serialize = "0.3.15"

sha1 = "0.1.1"

The library

rustc-serializecontains functions for encoding binary data in base64, and sha1, obviously, for hashing in SHA-1. The function that generates the response key is pretty simple:

extern crate sha1;

extern crate rustc_serialize;

use rustc_serialize::base64::{ToBase64, STANDARD};

fn gen_key(key: &String) -> String {

let mut m = sha1::Sha1::new();

let mut buf = [0u8; 20];

m.update(key.as_bytes());

m.update("258EAFA5-E914-47DA-95CA-C5AB0DC85B11".as_bytes());

m.output(&mut buf);

return buf.to_base64(STANDARD);

}

We get a link to the string with the key as an argument to the function

gen_key, create a new instance of the SHA-1 hash, add the key sent by the client to it, then add the constant string defined in the RFC and return the result as a string encoded in base64. But in order to use this function for its intended purpose, we first need to get a header from the client

Sec-WebSocket-Key. Let's get back to the HTTP parser from the previous section. As you remember, the type ParserHandlerallows us to redefine the callbacks that are called when new headers are received. Now is the time to take this opportunity - let's improve the implementation of the corresponding structure:use std::cell::RefCell;

use std::rc::Rc;

struct HttpParser {

current_key: Option,

headers: Rc>>

}

impl ParserHandler for HttpParser {

fn on_header_field(&mut self, s: &[u8]) -> bool {

self.current_key = Some(std::str::from_utf8(s).unwrap().to_string());

true

}

fn on_header_value(&mut self, s: &[u8]) -> bool {

self.headers.borrow_mut()

.insert(self.current_key.clone().unwrap(),

std::str::from_utf8(s).unwrap().to_string());

true

}

fn on_headers_complete(&mut self) -> bool {

false

}

}

This code itself is quite simple, but here we are faced with a new important concept - joint ownership .

As you already know, in Rust, a value can have only one owner, but at some points we may need to share ownership - for example, in this case we need to find a specific header in the hash table, but at the same time we need to write these headers in the parser. Thus, we get 2 owners of the variable

headers- WebSocketClientand ParserHandler.  To resolve this contradiction, Rust has a special type

To resolve this contradiction, Rust has a special type Rc- this is a wrapper with reference counting (which can be considered a type of garbage collection). In essence, we transfer ownership of the containerRc, which in turn can be safely divided into many owners with the help of black language magic - we simply clone the value Rcusing the function clone(), and the container manages the memory for us. True, there is a nuance - a value that contains

Rcimmutable , and because of the compiler's limitations, we cannot somehow influence it. In fact, this is just a consequence of the Rust rule regarding data volatility - you can have as many borrowings of a variable as you like, but you can change it only if there is only one owner.And here again there comes a contradiction - after all, we need to add new headers to the list, despite the fact that we are sure that we change this variable in only one place, so that we do not violate the Rust rules formally. Only the compiler will not agree with us on this score - when you try to change the contents

Rc, a compilation error will occur. But, of course, in the language there is a solution to this problem - it uses another type of container

RefCell. He solves it due to the mechanism of internal data volatility . Simply put, RefCellit allows us to put aside all the validation rules to the runtime (runtime) - instead of having to check them statically at compile time. Thus, we will need to wrap our headers in two containers at the same time - (which, of course, for unprepared minds looks pretty scary).

Let's look at these lines from a handler :Rc> HttpParserself.headers.borrow_mut()

.insert(self.current_key.clone().unwrap(),

...

Such a design as a whole corresponds to variable borrowing

&mut, with the difference that all checks to limit the number of borrowings will be carried out dynamically during program execution, so that we, and not the compiler, should carefully monitor this, otherwise a runtime error may occur. The

headersstructure will become the direct owner of the variable WebSocketClient, so let's add new properties to it and write a new constructor function:// Импортируем типы RefCell и Rc из стандартной библиотеки

use std::cell::RefCell;

use std::rc::Rc;

...

struct WebSocketClient {

socket: TcpStream,

http_parser: Parser,

// Добавляем определение заголовков в структуре WebSocketClient:

headers: Rc>>

}

impl WebSocketClient {

fn new(socket: TcpStream) -> WebSocketClient {

let headers = Rc::new(RefCell::new(HashMap::new()));

WebSocketClient {

socket: socket,

// Делаем первое клонирование заголовков для чтения:

headers: headers.clone(),

http_parser: Parser::request(HttpParser {

current_key: None,

// ... и второе клонирование для записи:

headers: headers.clone()

})

}

}

...

}

Now we

WebSocketClienthave access to parsed headers, and therefore we can find among them the one that interests us - Sec-WebSocket-Key. Given that we have a client key, the procedure for compiling a response will not cause any difficulties. We just need to collect the string in pieces and write it to the client socket. But since we cannot just send data to non-blocking sockets, we first need to ask the event loop to let us know about the socket's availability for recording. It is simple to do this - you need to change the set of flags

EventSetat EventSet::writable()the time of re-registration of the socket. Remember this line?

event_loop.reregister(&client.socket, token, EventSet::readable(),

PollOpt::edge() | PollOpt::oneshot()).unwrap();

We can store a set of events of interest to us in a client state - we will change the structure

WebSocketClient:struct WebSocketClient {

socket: TcpStream,

http_parser: Parser,

headers: Rc>>,

// Добавляем новое свойство, `interest`:

interest: EventSet

}

Now we will change the re-registration procedure accordingly:

event_loop.reregister(&client.socket, token,

client.interest, // Берем набор флагов `EventSet` из клиентской структуры

PollOpt::edge() | PollOpt::oneshot()).unwrap();

We only need to change the value

interestin the right places. To simplify this process, let's formalize it using connection states:#[derive(PartialEq)]

enum ClientState {

AwaitingHandshake,

HandshakeResponse,

Connected

}

Here we define an enumeration of all possible states for a client connected to the server. The first state

AwaitingHandshake,, means that we are expecting a new client to connect via HTTP. HandshakeResponsewill indicate the state when we respond via HTTP to the client. And, finally, the Connectedstate when we successfully established a connection with the client and communicate with it using the WebSocket protocol. Add a state variable to the client structure:

struct WebSocketClient {

socket: TcpStream,

http_parser: Parser,

headers: Rc>>,

interest: EventSet,

// Добавляем клиентское состояние:

state: ClientState

}

And add the initial values of the new variables to the constructor:

impl WebSocketClient {

fn new(socket: TcpStream) -> WebSocketClient {

let headers = Rc::new(RefCell::new(HashMap::new()));

WebSocketClient {

socket: socket,

...

// Initial events that interest us

interest: EventSet::readable(),

// Initial state

state: ClientState::AwaitingHandshake

}

}

}

Now we can change the state in the function

read. Remember these lines?match self.socket.try_read(&mut buf) {

...

Ok(Some(len)) => {

if self.http_parser.is_upgrade() {

// ...

break;

}

}

}

Change the stub in the condition block

is_upgrade()to the code for changing the connection status:if self.http_parser.is_upgrade() {

// Меняем текущее состояние на HandshakeResponse

self.state = ClientState::HandshakeResponse;

// Меняем набор интересующих нас событий на Writable

// (т.е. доступность сокета для записи):

self.interest.remove(EventSet::readable());

self.interest.insert(EventSet::writable());

break;

}

After we changed the set of flags of interest to

Writable, add the code needed to send a response to establish a connection. We will change the function

readyin the implementation of the structure WebSocketServer. The procedure for writing the response to the socket itself is simple (and practically does not differ from the reading procedure), and we only need to separate one type of event from the others:fn ready(&mut self, event_loop: &mut EventLoop,

token: Token, events: EventSet) {

// Мы имеем дело с чтением данных из сокета?

if events.is_readable() {

// Move all read handling code here

match token {

SERVER_TOKEN => { ... },

...

}

...

}

// Обрабатываем поступление оповещения о доступности сокета для записи:

if events.is_writable() {

let mut client = self.clients.get_mut(&token).unwrap();

client.write();

event_loop.reregister(&client.socket, token, client.interest,

PollOpt::edge() | PollOpt::oneshot()).unwrap();

}

}

Only a little remained - we need to collect in parts and send the response line:

use std::fmt;

...

impl WebSocketClient {

fn write(&mut self) {

// Заимствуем хеш-таблицу заголовков из контейнера Rc>:

let headers = self.headers.borrow();

// Находим интересующий нас заголовок и генерируем ответный ключ используя его значение:

let response_key = gen_key(&headers.get("Sec-WebSocket-Key").unwrap());

// Мы используем специальную функцию для форматирования строки.

// Ее аналоги можно найти во многих других языках (printf в Си, format в Python, и т.д.),

// но в Rust есть интересное отличие - за счет макросов форматирование происходит во время

// компиляции, и в момент выполнения выполняется только уже оптимизированная "сборка" строки

// из кусочков. Мы обсудим использование макросов в одной из следующих частей этой статьи.

let response = fmt::format(format_args!("HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols\r\n\

Connection: Upgrade\r\n\

Sec-WebSocket-Accept: {}\r\n\

Upgrade: websocket\r\n\r\n", response_key));

// Запишем ответ в сокет:

self.socket.try_write(response.as_bytes()).unwrap();

// Снова изменим состояние клиента:

self.state = ClientState::Connected;

// И снова поменяем набор интересующих нас событий на `readable()` (на чтение):

self.interest.remove(EventSet::writable());

self.interest.insert(EventSet::readable());

}

}

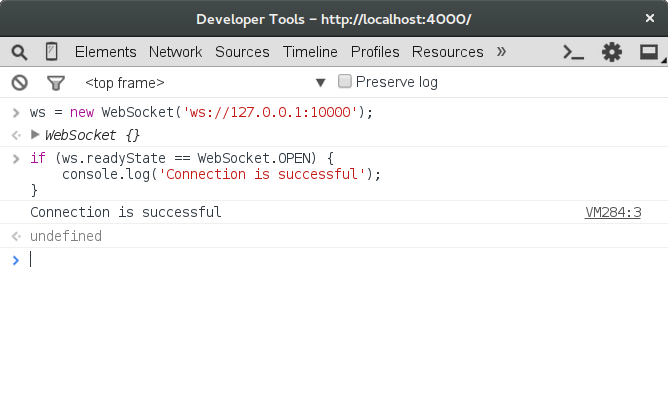

Let's try to connect to our server. Open the development console in your favorite browser (by pressing F12, for example), and enter the following code:

ws = new WebSocket('ws://127.0.0.1:10000');

if (ws.readyState == WebSocket.OPEN) {

console.log('Connection is successful');

}

Everything seems to be working - we are connected to the server!

Conclusion

Our fascinating journey through the possibilities and unusual concepts of the Rust language came to an end, but we touched only on the very beginning - a series of articles will be continued (of course, the sequels will be just as long and boring! :)). We need to consider many other interesting issues: secure TLS connections, multi-threaded event cycles, load testing and optimization, and, of course, the most important thing - we still need to finish the WebSocket protocol implementation and write the chat application itself.

But before we get to the application, you will need to do a little refactoring and separating the library code from the application code. Most likely, we will also consider publishing our library at crates.io .

All current code is available on Github., you can fork the repository and try changing something in it.

To monitor the appearance of the following parts of the article, I suggest following me on Twitter .

See you soon!

Notes

[1] It should be noted, Rust that essentially uses smart pointers to the level of language - the idea of borrowing is very similar to the types

unique_ptrand shared_ptrfrom C ++. [2] For example, the C encoding standard at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the automotive industry standard MISRA C generally prohibit the use of dynamic memory allocation through

malloc(). Instead, it assumes the allocation of local variables on the stack and the use of preallocated memory.[3] Simple garbage collection algorithms are fairly easy to use, however, more complex options like multi-threaded assembly may require considerable implementation effort. For example, in Go, multi-threaded garbage collection appeared only to version 1.5, which came out almost 3 years after the first.

[4] Generally speaking, many function implementations

malloc()also free()have the same problem due to memory fragmentation . [5] “Graydon Hoar [...] began work on a new programming language called Rust in 2006.” - InfoQ: “Interview On Rust”

[6] The man page

pthread_create(3)talks about 2 MB on a 32-bit Linux system. [7] To compare epoll with other system APIs, I recommend that you read the publication “Comparing and Evaluating epoll, select, and poll Event Mechanisms ”, University of Waterloo, 2004

[8]“ Kqueue: A generic and scalable event notification facility ”(

9)“ NGINX from the inside: born for performance and scaling . ”

I express gratitude for the help:

podust for illustrations and proofreading.

VgaCich for reading drafts and proofreading.