Homomorphic Encryption

What it is?

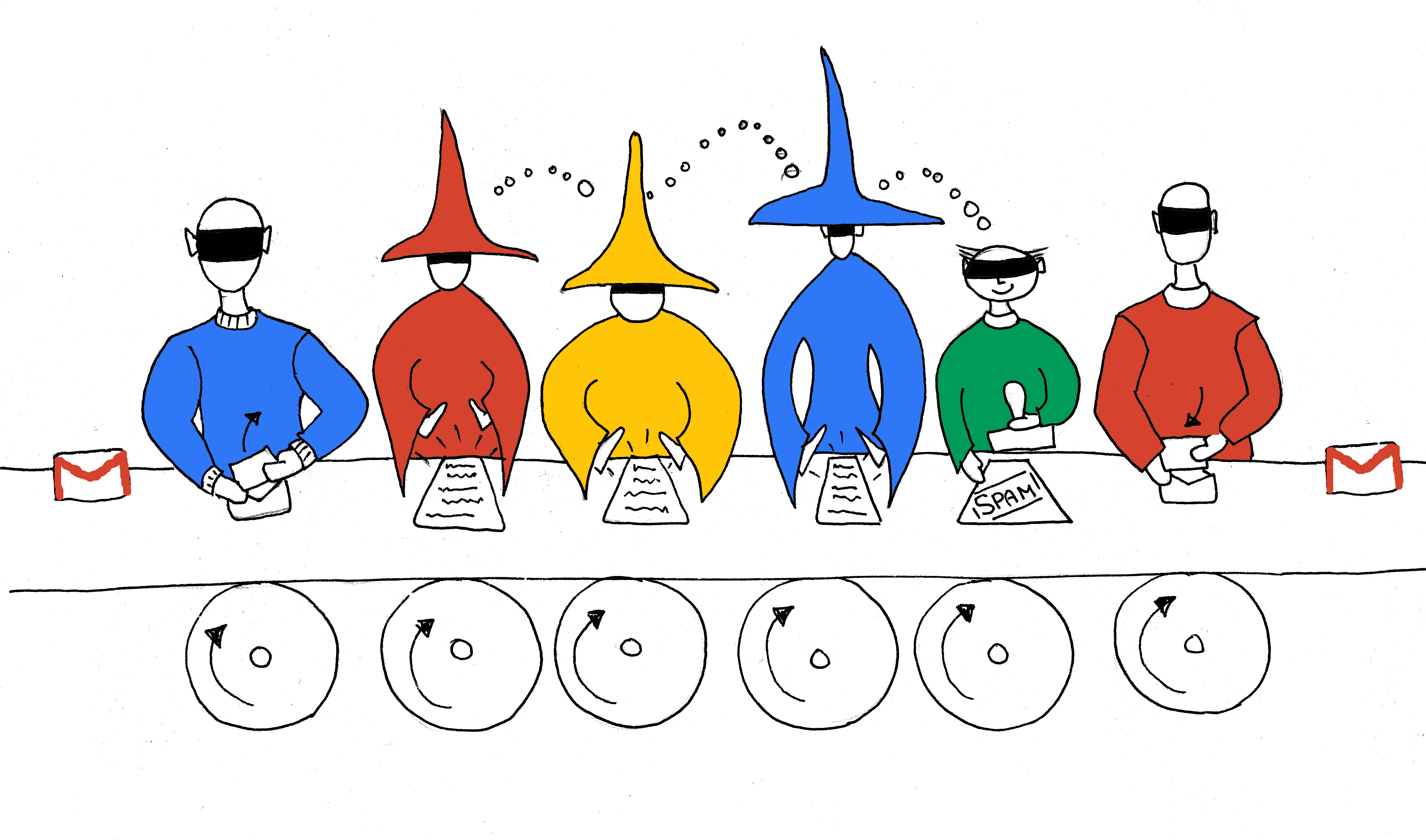

Fully Homomorphic Encryption for a very long time was the most striking discovery in the young and rapidly growing field of Computer Science - cryptography. In short, this type of encryption allows you to do arbitrary calculations on encrypted data without decrypting it. For example, Google can search by request without knowing what the request is, you can filter spam without reading emails, count votes without opening envelopes with votes, do DNA tests without reading DNA and much, much more.

That is, the person / machine / server performing the calculations performs mechanical operations with ciphers, executing its own algorithm (database search, spam analysis, etc.), but does not have any idea about the information encrypted inside. Only the user who has encrypted his data can decrypt the result of the calculation.

Great, right? And this is not from the realm of fantasy - this is something that can already be "theoretically" implemented.

From theory to practice, it’s not always, however, at hand, and sometimes it takes decades. Operations in modern homomorphic encryption schemes are much slower than usual and, according to Moore’s law, will become comparable to the computational speed today after 40 years. But every year, schemes become simpler and faster, so who knows, a new milestone may be just around the corner. IT technology.

History of creation

The history of the first scheme is rather unusual: Stanford University professor Dan Boneh made it a rule for all newly arrived graduate students to offer the "Automatic PhD problem". As a rule, this is a very difficult (but not grave) cryptography task, over which scientists have been fighting for at least ten years now. In 2006, Dan proposed the design of Fully Homomorphic Encryption to his new student, Craig Gentry. Two years later, Craig decided it. Dan kept his promise and Craig was one of the first students to get a Ph.D. so quickly. Having a long-standing passion for mathematics, Craig received his first law degree and worked as a lawyer for some time, until at a fairly conscious age he decided to return to mathematics and entered Stanford's graduate school.

Simple idea

The schemes for completely homomorphic encryption were initially understood only by specialists in number theory, but over the past 5 years they have become so simplified that their basic idea can be explained to the student.

So, imagine that you want to encrypt the number x (maybe this is just another bit of your data, maybe a small natural number). Choose an arbitrary vector v (it will be your secret key). It is possible to find a matrix A such that Av ~ = xv, i.e. the product of A by v will give approximately a vector v times x (for those who remember a little algebra, v will be an “approximate” eigenvector, and x will be an “approximate” eigenvalue of A). If you want to encrypt the new number y, then again it will be possible to find a matrix B such that Bv ~ = yv. Thus, you can, having only one secret key v, encrypt as many numbers as you like, where the matrix of each number is the matrix. To decrypt the number, we multiply the matrix by the secret vector v.

It can be proved, assuming the complexity of one archaic problem of finding a short vector in a lattice, which is also difficult, having matrices A and B, with a significant probability (distinguishable from random guessing) to say which numbers x and y they encrypt (without knowing, of course, the secret vector v)

So this is really a cryptographic scheme, but it is also homomorphic! That is, operating with the matrices A and B, namely, multiplying and adding them, we will multiply and add the numbers that they encrypt. Indeed, let's see what the decryption of the product of A and B gives:

(AB) v = A (Bv) ~ = A xv = x (Av) ~ = (xy) v, it gives the product of x and y!

And deciphering the sum of A and B will give

(A + B) v = Av + Bv ~ = xv + yv ~ = (x + y) v, the sum of x and y!

Of course, more precise analysis is required here to make sure that approximate equality is preserved. Also, finding an encryption matrix is not a completely trivial task, but it’s quite possible to figure it out if you dive into a few good articles for a while, like this one:

[GSW'13] “Homomorphic Encryption from Learning with Errors: Conceptually-Simpler, Asymptotically- Faster, Attribute-Based "( pdf )

Window to a new world

Craig opened the door to a kind of new world. Today we have a huge number of variations of homomorphic encryption and the most interesting is that one of the variations can give the best possible, theoretically the most stable way to obfuscate programs, and this will open up even more possibilities for imagination! But more about that another time. If you are interested in the current task, for the solution of which Dan gives PhD automatically, write in the comments;)