British Biomarker Panel Healthy Aging

A team of British gerontologists from universities in Cambridge, Birmingham, Edinburgh and Newcastle conducted a study, which resulted in a panel of biomarkers for healthy aging.

We express our disagreement with the term “healthy aging”, since it is an oxymoron, aging is a loss of health, an unhealthy phenomenon in itself. Nevertheless, the term such exists and we will consider this approach, based on the opinion of the authors of the article.

Studies on healthy aging include:

Such studies require markers of biological aging at the individual level, which, in addition to chronological age, can characterize and quantify important functions that decrease more rapidly or more slowly during individual aging of a person.

Biomarkers for healthy aging can be useful as reference points. Especially in various trials related to the therapy and prevention of age-related diseases that will benefit from reliable, easily measured indicators of healthy aging.

However, there is no criterion for evaluating healthy aging, and this makes it difficult to conduct and compare research on aging.

Over the past 50 years there have been several attempts to develop markers of aging, but the complexity of the aging phenotype poses practical difficulties along the way.

Despite all efforts, there is no generally accepted definition of biomarkers of aging and their selection criteria, which has resulted in the lack of reliable, proven tools for assessing healthy aging.

The American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR) has proposed the following criteria for aging biomarkers:

Based on these requirements, finding biomarkers that meet all the AFAR criteria listed above will not be easy. Despite this, a number of candidates for aging biomarkers have appeared in the past few decades.

Aging affects all cells, organs and tissues, and in most body systems it is characterized by a gradual loss of function. Extensive functional losses have profound implications for a person, his family members and carers. All this has the widest implications for the whole society. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify a group of objective biomarkers of healthy aging in humans.

Where healthy aging is defined as maintaining body functions for a maximum period of time. Such biomarkers should characterize and quantify important functions that deteriorate during aging, and for which there are reliable, easily applied tools for their evaluation.

To search for such biomarkers, British researchers have focused on several areas:

Such important subjective features of the phenomenon of healthy aging as psychological and social well-being were not considered. The proposed group of markers was chosen from those that are best identified and for which there is strong evidence supporting strong associations with aging phenotypes. Which are likely to be cost effective and practical for use in larger studies.

Most literature focuses on morbidity and mortality in the form of phenotypes or end points of aging. And there is no independent, benchmarked, reference indicator of healthy aging, based on which existing or new biomarkers can be assessed.

Based on this and in line with current efforts to standardize the definitions and roles of biomarkers, the proposed group of biomarkers includes a set of items related to important functions affecting the aging process.

In their work, the researchers set themselves the task of identifying objectively evaluated biomarkers that are commonly used in population studies and are applicable in various conditions (that is, they are not limited to use in laboratory conditions / clinics). Which allow you to define healthy and unhealthy aging in older people, changing in individuals over time.

The research base in some areas, for example, in determining the age-related immune function, was less developed than in others, for example, in terms of physical capabilities. Also, researchers, along with the main group of biomarkers, identified several promising biomarkers, for which there is not yet sufficient evidence and more research is needed.

Fig.1 Proposed group of biomarkers for healthy aging.

1. Green - biomarkers of physiological function.

a) cardiovascular (blood lipids, blood pressure)

b) lung function (forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1)

c) glucose metabolism (glycated hemoglobin, fasting glucose)

d) body composition (bone density, muscle mass).

2. Violet color - biomarkers of endocrine function.

a) Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (DHEAS, cortisol).

b) sex hormones (testosterone, estrogen)

c) growth hormones (growth hormone, IGF-1).

3. Blue-green - biomarkers of physical ability

a) strength (hand compressive strength)

b) balance (constant balance)

c) vvkost (Purgee Pegboard test)

d) locomotor function (gait speed, Timed Up and Go test, raising from a chair )

4. Gray - the biomarkers of the conservative function.

a) memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning test)

b) processing speed (digital character coding)

c) executive functions (speech speed).

5. Red color - biomarkers of immune function.

a) inflammatory factors (IL-6, TNF-α)

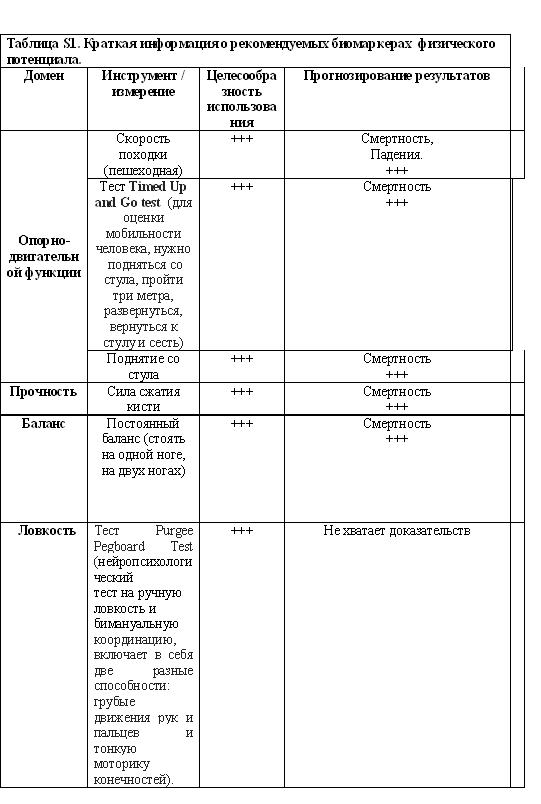

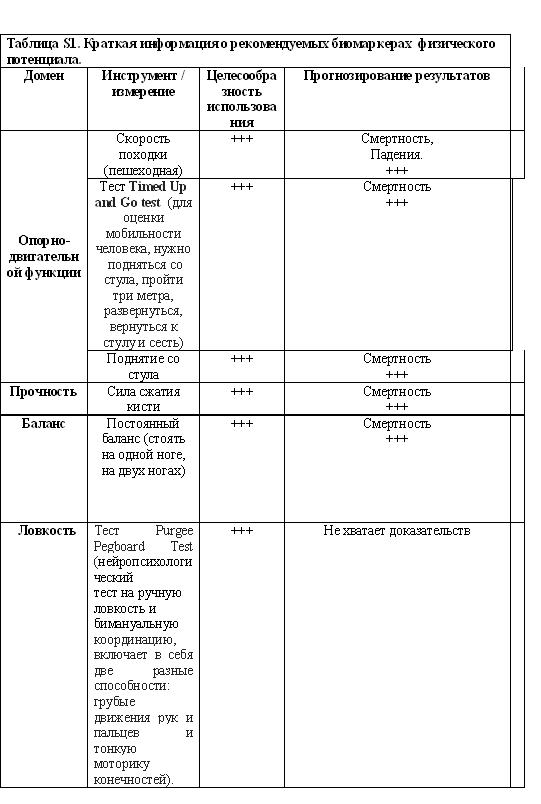

Indicators of physical ability, that is, the ability of a person to perform the physical tasks of everyday life, are useful markers of modern and future health. Guided by the results of the HALCyon study and the NIH toolkit, the researchers chose four items for measurements: locomotor function; brush grip strength; balance; agility.

Physical ability gradually decreases at a later age. Poor performance in tests for brushing force, walking speed, time to rise from the chair (the patient is asked to get up from the chair 5 times in a row with his arms folded on his chest, his knees should be fully extended with each lift, the test gives information about the strength and speed of the muscles lower extremities) and constant balance are associated with higher mortality.

In addition, lower levels of physical performance are associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular diseases, dementia, and difficulties associated with daily activities.

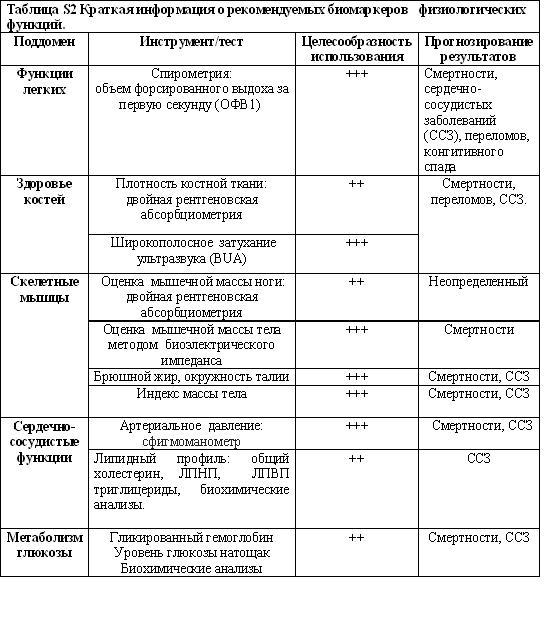

Note. The degree of expediency of use and prediction of results: +++ strong; ++ moderate + low.

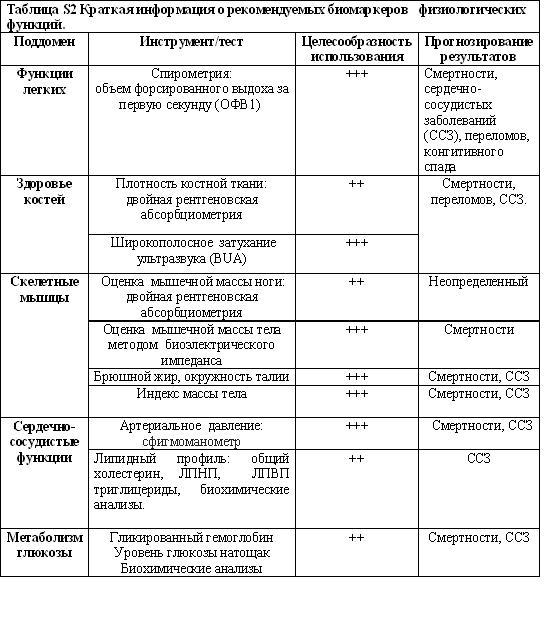

Complex molecular changes that affect the structure and function of most cells, tissues, and body systems are a hallmark of aging. And changes in their functions can be detected after 30 years of life. Here, researchers focused on biomarkers of lung function, body composition (including bone mass and skeletal muscle), cardiovascular system and glucose metabolism.

With age, after 25 years, the volume of forced expiration decreases by about 32 ml per year for men and 25 ml per year for women. And the lower this figure, the worse the entire functional status of the organism. The forced expiratory volume indicator has an inverse relationship with mortality - the smaller this indicator, the higher the mortality rate.

Bone mass also decreases with age, and bone mass or density predicts the risk of future fractures and mortality. Larger waist circumference, body mass index and weight gain in middle age are associated with higher mortality and lower survival rates. In addition, a decrease in skeletal muscle mass is associated with an increased likelihood of functional impairment and disability.

Blood pressure and blood lipids are currently the strongest predictors of morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular diseases.

An increase in blood pressure is associated with an increased risk of mortality, and an increase in pressure in middle age is associated with a decrease in cognitive functions in a later period of life.

Also, aging is associated with impaired glucose homeostasis. Elevated fasting blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) are associated with age, cardiovascular diseases and mortality, as well as cognitive impairment and dementia in non-diabetic patients.

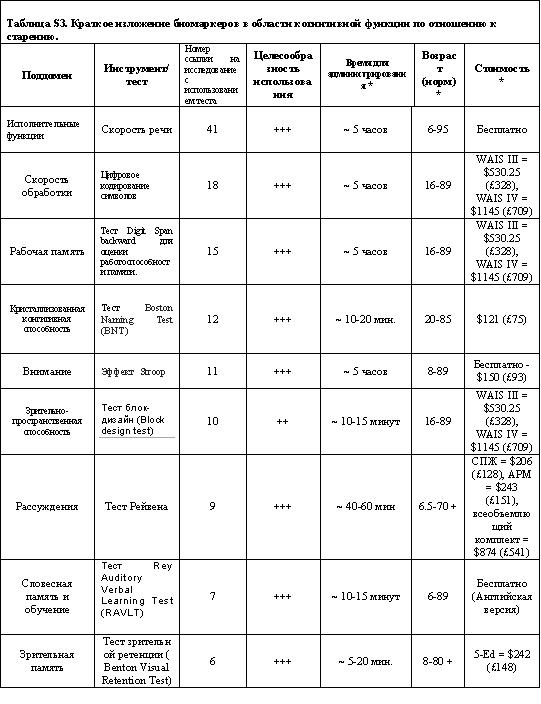

Cognitive decline can limit independence and warn of impending dementia. Evidence suggests that the onset of cognitive decline is found relatively early in adulthood, at about 45 years of age, or even earlier in some functions.

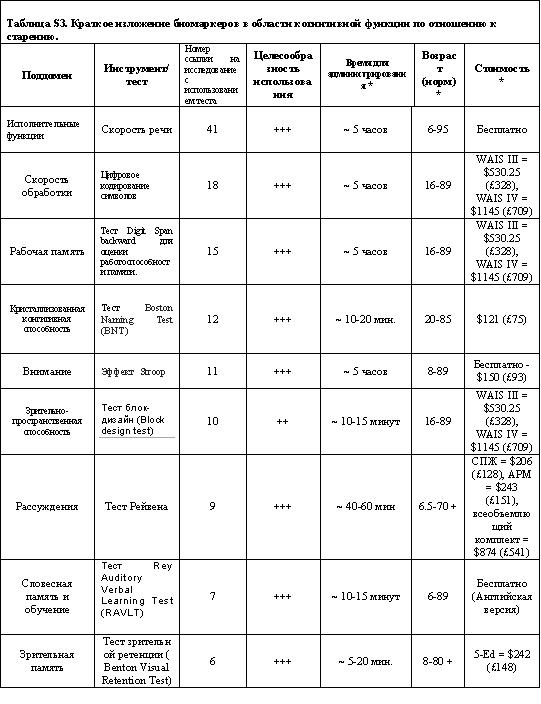

The researchers focused on cognitive positions, which were widely evaluated in human aging studies and used in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) toolkit. Nine domains were identified along with tests that are commonly used to evaluate them.

Based on the available data, the three areas — executive functions, processing speed, and episodic memory — are a possible minimum set of areas to be assessed in aging studies. Also useful additions will be special tests of crystallized cognitive ability and non-verbal reasoning.

The executive function noticeably affects aging, demonstrating an inverted U-shape throughout life. The processing speed decreases gradually with age and is associated with a high risk of mortality, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. In addition, episodic memory is sensitive to brain aging and decreases in people with mild cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative diseases.

Age-related changes in the endocrine system, especially sex hormones, are well known and have established cause-effect relationships with health.

Here, researchers focused on sex hormones, growth hormone, IGF-1, melatonin, adipokines (adipose tissue hormones) and thyroid hormones. Earlier evidence from longitudinal studies indicate that testosterone, estrogen, DHEAS (dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate), growth hormone and IGF-1 are associated with the risk of premature mortality and physical weakness.

For some biomarkers, the association with aging appears to be non-linear, for example, both high and low levels of IGF-1 are associated with greater mortality. DHEAS decreases with age, starting from the third decade of life, and low DHEAS levels are associated with an increase in mortality in elderly patients and senile asthenia.

Testosterone and estrogen are associated with physical weakness and bone health. Cortisol is associated with age-related diseases and disabilities, and abnormal cortisol secretion patterns are associated with an increase in blood pressure, impaired glucose metabolism and an increase in the incidence of cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes in men.

At the same time, the authors note that additional evidence is needed for a better understanding of the relationship between cortisol and DHEAS, between DHEAS and adipokines (adiponectin, leptin, ghrelin), somatostatin and aging, frailty and mortality.

Although the field of immunology is well developed, the study of the age-related decline of immunity, called immunogenicity, began much later. Here, the authors focused on age-related immune function and inflammatory factors.

Longitudinal studies comparing immune cells and their functions with mortality, or with age-related functions, such as infection rates or vaccination responses, are currently insufficient.

As a basis for describing the immune risk profile (IRP), studies on the analysis of immune markers (T cell phenotype, cytomegalovirus serostat and proinflammatory cytokine status) and their connection with subsequent mortality in people over 60 years old were used.

The weak point of the IRP is that it does not take into account innate immune factors, such as the function of natural killer cells (NK cells), which is associated with infection rates and mortality. The most studied aspect of immunogenicity is the age-related increase in systemic inflammatory cytokines and inflammation. Higher plasma concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α are associated with lower grip strength and walking speed in the elderly. Centenarian long-livers show fewer signs of aging of the immune system, although they have some inflammation.

At the same time, it is noted that longitudinal studies should examine the relationship between the number and function of T cells, neutrophils, NK cells, B cells and mortality, the risk of age-related diseases and well-being in the later period of life.

Given the transition from lymphoid cell production to myeloid cells with age, the lymphocyte / granulocyte ratio is a potentially useful biomarker for healthy aging. The IRP needs to be tested in young people and needs to be expanded to include indicators of immune function, such as infectious diseases or a response to vaccination.

The length of telomeres in leukocytes, including lymphocytes and monocytes, has attracted increased attention. Despite its association with aging in several studies, it is likely that shorter telomeres are also a marker of the frequency of infection, so leukocyte telomere length cannot be a reliable indicator of biological aging.

Further studies on telomere length and aging should include a study of the effects of infections and cytomegalovirus seropositivity as possible factors. For example, in the Newcastle 85+ study, telomere length was uninformative with respect to health.

Note: +++++ is very strong; ++++ strong, +++ moderate, ++ low, + very low or not;

Sensory functions are crucial for normal levels of independence, for interacting with other people and for alleviating life. The loss of these functions is more common in older people, and the loss of hearing and vision is most noticeable.

The prevalence of visual impairment increases with age and can reduce the ability to take daily actions, such as reading, and limit mobility and social interactions. Visual acuity decreases with age, is more common in men and is suggested as an indicator of brain integrity in older people.

Olfactory dysfunction is one of the earliest “preclinical” signs of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, and is associated with mortality, as shown by the National Social Life project, the Health and Aging Project. The NIH toolkit includes measurements of hearing, vision, smell, taste, vestibular function, and pain. Most of these functions, with the exception of pain, diminish throughout life, and sensory changes may overlap with changes in cognitive and motor functions. However, the predicted value of sensory function measurements for age-related health outcomes remains uncertain, as is the ability to modulate age-related changes in sensory function through lifestyle or other interventions.

The proposed group includes biomarkers such as blood pressure, fasting glucose and HbA1C, bone mineral density and blood lipids, each of which is considered to be associated with the disease. And therefore, they do not quite correspond to the second paragraph of the criteria for determining AFAR.

However, these biomarkers appear to predict the biological age and rate of aging in younger healthy subjects. In these population strata, changes in biomarkers seem to reflect subtle changes in the processes associated with aging (probably due to differences in the rate of accumulation of molecular damage), rather than outright illness.

Today there is a scientific interest in a number of “new” biomarkers of aging, some of which are being studied in research initiatives, such as the MARK-AGE consortium in Europe.

Researchers suggest that combinations of some of these biomarkers appear to predict biological age and aging among young people, as well as senile asthenia (frailty). And further research in this area should help determine which biomarkers can be combined to obtain a general “aging indicator” and the circumstances in which such an indicator is of practical use.

Another common limitation of this study, according to the authors, is the uncertainty about the reliability of the supposedly healthy biomarkers of healthy aging in very old people, which seem to be reliable in younger people.

Indeed, in some cases the opposite effect may be observed. As for example, in the case of high blood pressure, which in very old people can perform a protective function. The researchers tried to focus on biologically understandable objective parameters that could be used globally in a wider range of different types of research.

This study was commissioned by the Medical Research Council (MRC), United Kingdom, to address the gap associated with biomarkers for healthy aging.

Prepared by: Alexey Rzheshevsky.

We express our disagreement with the term “healthy aging”, since it is an oxymoron, aging is a loss of health, an unhealthy phenomenon in itself. Nevertheless, the term such exists and we will consider this approach, based on the opinion of the authors of the article.

Studies on healthy aging include:

- Biological processes that contribute to aging;

- Socio-economic and environmental impacts on life, which modulate aging and the risk of age-related instability, disability and disease;

- Various interventions that can affect the trajectory of aging.

Such studies require markers of biological aging at the individual level, which, in addition to chronological age, can characterize and quantify important functions that decrease more rapidly or more slowly during individual aging of a person.

Biomarkers for healthy aging can be useful as reference points. Especially in various trials related to the therapy and prevention of age-related diseases that will benefit from reliable, easily measured indicators of healthy aging.

However, there is no criterion for evaluating healthy aging, and this makes it difficult to conduct and compare research on aging.

Over the past 50 years there have been several attempts to develop markers of aging, but the complexity of the aging phenotype poses practical difficulties along the way.

Despite all efforts, there is no generally accepted definition of biomarkers of aging and their selection criteria, which has resulted in the lack of reliable, proven tools for assessing healthy aging.

The American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR) has proposed the following criteria for aging biomarkers:

- They must predict the rate of aging (i.e., determine exactly where a person is in their total life expectancy, and this should be a more accurate prediction of life expectancy than the chronological age);

- They should control the main process that underlies the aging process, not the effects of the disease;

- They should provide an opportunity to be retested without harming a person (for example, a blood test or imaging method);

- It must be something that works on humans and on laboratory animals, such as mice (so that they can be tested on laboratory animals before they are tested on humans). "

Based on these requirements, finding biomarkers that meet all the AFAR criteria listed above will not be easy. Despite this, a number of candidates for aging biomarkers have appeared in the past few decades.

Aging affects all cells, organs and tissues, and in most body systems it is characterized by a gradual loss of function. Extensive functional losses have profound implications for a person, his family members and carers. All this has the widest implications for the whole society. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify a group of objective biomarkers of healthy aging in humans.

Where healthy aging is defined as maintaining body functions for a maximum period of time. Such biomarkers should characterize and quantify important functions that deteriorate during aging, and for which there are reliable, easily applied tools for their evaluation.

To search for such biomarkers, British researchers have focused on several areas:

- physical ability, cognition,

- functions of the musculoskeletal system,

- physiological,

- endocrine,

- immune and sensory functions.

Such important subjective features of the phenomenon of healthy aging as psychological and social well-being were not considered. The proposed group of markers was chosen from those that are best identified and for which there is strong evidence supporting strong associations with aging phenotypes. Which are likely to be cost effective and practical for use in larger studies.

Most literature focuses on morbidity and mortality in the form of phenotypes or end points of aging. And there is no independent, benchmarked, reference indicator of healthy aging, based on which existing or new biomarkers can be assessed.

Based on this and in line with current efforts to standardize the definitions and roles of biomarkers, the proposed group of biomarkers includes a set of items related to important functions affecting the aging process.

In their work, the researchers set themselves the task of identifying objectively evaluated biomarkers that are commonly used in population studies and are applicable in various conditions (that is, they are not limited to use in laboratory conditions / clinics). Which allow you to define healthy and unhealthy aging in older people, changing in individuals over time.

The research base in some areas, for example, in determining the age-related immune function, was less developed than in others, for example, in terms of physical capabilities. Also, researchers, along with the main group of biomarkers, identified several promising biomarkers, for which there is not yet sufficient evidence and more research is needed.

Fig.1 Proposed group of biomarkers for healthy aging.

1. Green - biomarkers of physiological function.

a) cardiovascular (blood lipids, blood pressure)

b) lung function (forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1)

c) glucose metabolism (glycated hemoglobin, fasting glucose)

d) body composition (bone density, muscle mass).

2. Violet color - biomarkers of endocrine function.

a) Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (DHEAS, cortisol).

b) sex hormones (testosterone, estrogen)

c) growth hormones (growth hormone, IGF-1).

3. Blue-green - biomarkers of physical ability

a) strength (hand compressive strength)

b) balance (constant balance)

c) vvkost (Purgee Pegboard test)

d) locomotor function (gait speed, Timed Up and Go test, raising from a chair )

4. Gray - the biomarkers of the conservative function.

a) memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning test)

b) processing speed (digital character coding)

c) executive functions (speech speed).

5. Red color - biomarkers of immune function.

a) inflammatory factors (IL-6, TNF-α)

Physical performance biomarkers

Indicators of physical ability, that is, the ability of a person to perform the physical tasks of everyday life, are useful markers of modern and future health. Guided by the results of the HALCyon study and the NIH toolkit, the researchers chose four items for measurements: locomotor function; brush grip strength; balance; agility.

Physical ability gradually decreases at a later age. Poor performance in tests for brushing force, walking speed, time to rise from the chair (the patient is asked to get up from the chair 5 times in a row with his arms folded on his chest, his knees should be fully extended with each lift, the test gives information about the strength and speed of the muscles lower extremities) and constant balance are associated with higher mortality.

In addition, lower levels of physical performance are associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular diseases, dementia, and difficulties associated with daily activities.

Note. The degree of expediency of use and prediction of results: +++ strong; ++ moderate + low.

Biomarkers of physiological function

Complex molecular changes that affect the structure and function of most cells, tissues, and body systems are a hallmark of aging. And changes in their functions can be detected after 30 years of life. Here, researchers focused on biomarkers of lung function, body composition (including bone mass and skeletal muscle), cardiovascular system and glucose metabolism.

With age, after 25 years, the volume of forced expiration decreases by about 32 ml per year for men and 25 ml per year for women. And the lower this figure, the worse the entire functional status of the organism. The forced expiratory volume indicator has an inverse relationship with mortality - the smaller this indicator, the higher the mortality rate.

Bone mass also decreases with age, and bone mass or density predicts the risk of future fractures and mortality. Larger waist circumference, body mass index and weight gain in middle age are associated with higher mortality and lower survival rates. In addition, a decrease in skeletal muscle mass is associated with an increased likelihood of functional impairment and disability.

Blood pressure and blood lipids are currently the strongest predictors of morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular diseases.

An increase in blood pressure is associated with an increased risk of mortality, and an increase in pressure in middle age is associated with a decrease in cognitive functions in a later period of life.

Also, aging is associated with impaired glucose homeostasis. Elevated fasting blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) are associated with age, cardiovascular diseases and mortality, as well as cognitive impairment and dementia in non-diabetic patients.

Biomarkers of cognitive function

Cognitive decline can limit independence and warn of impending dementia. Evidence suggests that the onset of cognitive decline is found relatively early in adulthood, at about 45 years of age, or even earlier in some functions.

The researchers focused on cognitive positions, which were widely evaluated in human aging studies and used in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) toolkit. Nine domains were identified along with tests that are commonly used to evaluate them.

Based on the available data, the three areas — executive functions, processing speed, and episodic memory — are a possible minimum set of areas to be assessed in aging studies. Also useful additions will be special tests of crystallized cognitive ability and non-verbal reasoning.

The executive function noticeably affects aging, demonstrating an inverted U-shape throughout life. The processing speed decreases gradually with age and is associated with a high risk of mortality, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. In addition, episodic memory is sensitive to brain aging and decreases in people with mild cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative diseases.

Biomarkers of Endocrine Function

Age-related changes in the endocrine system, especially sex hormones, are well known and have established cause-effect relationships with health.

Here, researchers focused on sex hormones, growth hormone, IGF-1, melatonin, adipokines (adipose tissue hormones) and thyroid hormones. Earlier evidence from longitudinal studies indicate that testosterone, estrogen, DHEAS (dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate), growth hormone and IGF-1 are associated with the risk of premature mortality and physical weakness.

For some biomarkers, the association with aging appears to be non-linear, for example, both high and low levels of IGF-1 are associated with greater mortality. DHEAS decreases with age, starting from the third decade of life, and low DHEAS levels are associated with an increase in mortality in elderly patients and senile asthenia.

Testosterone and estrogen are associated with physical weakness and bone health. Cortisol is associated with age-related diseases and disabilities, and abnormal cortisol secretion patterns are associated with an increase in blood pressure, impaired glucose metabolism and an increase in the incidence of cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes in men.

At the same time, the authors note that additional evidence is needed for a better understanding of the relationship between cortisol and DHEAS, between DHEAS and adipokines (adiponectin, leptin, ghrelin), somatostatin and aging, frailty and mortality.

Immune function biomarkers

Although the field of immunology is well developed, the study of the age-related decline of immunity, called immunogenicity, began much later. Here, the authors focused on age-related immune function and inflammatory factors.

Longitudinal studies comparing immune cells and their functions with mortality, or with age-related functions, such as infection rates or vaccination responses, are currently insufficient.

As a basis for describing the immune risk profile (IRP), studies on the analysis of immune markers (T cell phenotype, cytomegalovirus serostat and proinflammatory cytokine status) and their connection with subsequent mortality in people over 60 years old were used.

The weak point of the IRP is that it does not take into account innate immune factors, such as the function of natural killer cells (NK cells), which is associated with infection rates and mortality. The most studied aspect of immunogenicity is the age-related increase in systemic inflammatory cytokines and inflammation. Higher plasma concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α are associated with lower grip strength and walking speed in the elderly. Centenarian long-livers show fewer signs of aging of the immune system, although they have some inflammation.

At the same time, it is noted that longitudinal studies should examine the relationship between the number and function of T cells, neutrophils, NK cells, B cells and mortality, the risk of age-related diseases and well-being in the later period of life.

Given the transition from lymphoid cell production to myeloid cells with age, the lymphocyte / granulocyte ratio is a potentially useful biomarker for healthy aging. The IRP needs to be tested in young people and needs to be expanded to include indicators of immune function, such as infectious diseases or a response to vaccination.

The length of telomeres in leukocytes, including lymphocytes and monocytes, has attracted increased attention. Despite its association with aging in several studies, it is likely that shorter telomeres are also a marker of the frequency of infection, so leukocyte telomere length cannot be a reliable indicator of biological aging.

Further studies on telomere length and aging should include a study of the effects of infections and cytomegalovirus seropositivity as possible factors. For example, in the Newcastle 85+ study, telomere length was uninformative with respect to health.

Note: +++++ is very strong; ++++ strong, +++ moderate, ++ low, + very low or not;

Sensory functions as potential biomarkers of aging

Sensory functions are crucial for normal levels of independence, for interacting with other people and for alleviating life. The loss of these functions is more common in older people, and the loss of hearing and vision is most noticeable.

The prevalence of visual impairment increases with age and can reduce the ability to take daily actions, such as reading, and limit mobility and social interactions. Visual acuity decreases with age, is more common in men and is suggested as an indicator of brain integrity in older people.

Olfactory dysfunction is one of the earliest “preclinical” signs of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, and is associated with mortality, as shown by the National Social Life project, the Health and Aging Project. The NIH toolkit includes measurements of hearing, vision, smell, taste, vestibular function, and pain. Most of these functions, with the exception of pain, diminish throughout life, and sensory changes may overlap with changes in cognitive and motor functions. However, the predicted value of sensory function measurements for age-related health outcomes remains uncertain, as is the ability to modulate age-related changes in sensory function through lifestyle or other interventions.

The proposed group includes biomarkers such as blood pressure, fasting glucose and HbA1C, bone mineral density and blood lipids, each of which is considered to be associated with the disease. And therefore, they do not quite correspond to the second paragraph of the criteria for determining AFAR.

However, these biomarkers appear to predict the biological age and rate of aging in younger healthy subjects. In these population strata, changes in biomarkers seem to reflect subtle changes in the processes associated with aging (probably due to differences in the rate of accumulation of molecular damage), rather than outright illness.

Today there is a scientific interest in a number of “new” biomarkers of aging, some of which are being studied in research initiatives, such as the MARK-AGE consortium in Europe.

Researchers suggest that combinations of some of these biomarkers appear to predict biological age and aging among young people, as well as senile asthenia (frailty). And further research in this area should help determine which biomarkers can be combined to obtain a general “aging indicator” and the circumstances in which such an indicator is of practical use.

Another common limitation of this study, according to the authors, is the uncertainty about the reliability of the supposedly healthy biomarkers of healthy aging in very old people, which seem to be reliable in younger people.

Indeed, in some cases the opposite effect may be observed. As for example, in the case of high blood pressure, which in very old people can perform a protective function. The researchers tried to focus on biologically understandable objective parameters that could be used globally in a wider range of different types of research.

This study was commissioned by the Medical Research Council (MRC), United Kingdom, to address the gap associated with biomarkers for healthy aging.

Prepared by: Alexey Rzheshevsky.

A source

Jose Lara, Rachel Cooper, Jack Nissan, Annie T Ginty, Kay-Tee Khaw, Ian J Deary, Janet M Lord, Diana Kuh, and John C Mathers. A proposed panel of biomarkers of healthy ageing. BMC Med. 2015; 13: 222.