Bleeding Heart Status: Upgrade to Broken

- Transfer

For information: In many references to this article, the authors mistakenly call me an employee of Opera Software. In fact, I left Opera more than a year ago and today I work in a new company - Vivaldi Technologies AS

May 12th update

After a more thorough investigation of the problem, together with F5, it turned out that the test used to detect F5 BigIP servers showed higher numbers than it should be, so the number of such servers turned out to be overestimated during the check. This means that the relevant information about the BigIP servers and the conclusions are incorrect, so I will delete the chapter on BigIP servers. I apologize to F5 and their customers for this mistake.

Background

As I said in my previous article, a few weeks ago a vulnerability was discovered in the OpenSSL library ( CVE-2014-0160 ), which was loudly called " Heartbleed ". This vulnerability allowed attackers to extract such important information as, for example, user passwords or private encryption keys of sites, penetrating vulnerable “secure” web servers ( explanatory comic book ).

As a result, all the websites affected by this scourge had to patch their servers, as well as perform other actions to protect their users. It is worth noting that the level of danger increased significantly after information about the vulnerability scattered across the network (several serious incidents were recorded and at least one person who tried to use Heartbleed for personal gain was arrested).

Slowing Patch Usage

For several weeks since the day the vulnerability was discovered, I tracked the activity of applying the patch using my own TLS Prober tester. Currently, the tester scans approximately 500,000 individual servers using host name changes in various domains (totaling 23 million) with a sample of about a million websites from Alexa Top.

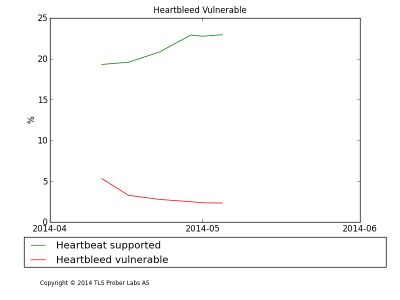

According to six scans I carried out from April 11, the number of vulnerable servers dropped sharply from 5.36% of the total number of servers being tested to 2.33% this week. About 20% of scanned servers support the Heartbeat TLS Extension, which means that up to 75% of vulnerable servers were patched during the first four days after the vulnerability was discovered, i.e. before my first scan.

However, if during the first two weeks of scanning the number of vulnerable servers was halved - to 2.77%, in the next couple of weeks this figure dropped to only 2.33%, which indicates an almost complete stop of the process of "treatment" of vulnerable servers.

In general, a scan shows that the servers of the most popular websites have been patched. About 73% of crawled websites use certificates from Certificate Authority recognized by browsers, and only 30% of vulnerable websites use such certificates. All this slightly reduces the importance of the problem as a whole, but even if some servers look insignificant on the scale of the entire Internet, it is not easier for real users of these servers.

There is an equally serious problem: many certificates used by vulnerable servers continue to be used on fixed servers. In fact, assuming that all servers that supported Heartbeat on the first scan were vulnerable to this, 2/3 of the certificates were not updated after fixing the servers using the patch (since they turned out to be the same as before the server fixing ) Given that each server patched after April 7 supposedly had a compromised certificate private key (after all, attackers could use Heartbleed on these servers), we can talk about a serious problem that still threatens users of such websites.

In addition, digging in numbers revealed two more problems.

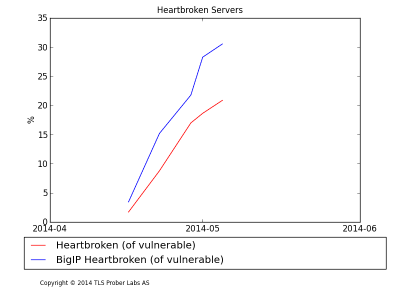

The first problem is that the absolute number of F5 BigIP servers (powerful SSL / TLS accelerators) with a specific configuration using vulnerable versions of OpenSSL remains unchanged. Identifying BigIP servers today is very easy, because they have problems with certain types of TLS handshakes.

True, the graph looks a little strange, because these types of BigIP servers were actually patched even better than most servers supporting Heartbeat.

The reason that the absolute number of vulnerable BigIP servers remained unchanged is as follows: the number of BigIP servers, including those using OpenSSL version 1.0.1 (with Heartbeat support), has doubled in the past month (after a slow decline over the past couple of years), and many new servers use a vulnerable version of the OpenSSL library.

I assume that part of the problem was created by the new owners of BigIP servers: perhaps they just forgot to update the original server software after installing it.

Given that BigIP servers are typically used to serve a large number of users, we can assume that they all have quite serious security problems.

Update to Broken Heart

The second problem is also related to the number of vulnerable BigIP servers, but it looks much worse: during my last scan, 20% of the currently vulnerable servers (IP sampling)

It could be assumed that the figures identified are incorrect, because the analysis assumes that the IP addresses of the servers are not changed, which does not always happen. However, applying the same technique to verify server certificates shows the same trend.

It is difficult to say exactly where this problem came from, but one of the possibilities is that the increased attention to the topic from the media made server administrators doubt that their servers are quite safe. To this could be added pressure from the authorities demanding “not to be idle,” as a result, software was updated that was completely protected from adversity of servers to a new version, which at that time had not yet been fixed by the developers themselves.

To fix this problem, owners of vulnerable servers will have to go through the entire patch process again, which will lead to money costs that could actually have been avoided. Roughly, applying a patch, replacing a certificate and conducting appropriate testing will require the work of three system administrators within four hours. With the cost of each admin hour at $ 40, the approximate total amount of unnecessary expenses for fixing 2500 “sick” servers (in my example) can be about $ 1.2 million. And considering that my testing covers only about 10% of all servers on the network, the total amount contingencies will total $ 12 million.

Heartbleed is a very serious problem and fixing this vulnerability needs to be done by all the servers affected by this “misfortune”, but I’m starting to think that the activity of the thematic press, which suffers from a lot of inaccuracies and gives premature advice (such as, for example, “change your password immediately!” without waiting for the server software update or “revocation of certificates due to Heartbleed will significantly slow down the network speed”), is to some extent counterproductive.

The aforementioned data on servers that were “updated” and thus became vulnerable to a problem that had not previously been addressed to them may be the result of a distorted press coverage of the problem.

My recommendations remain unchanged: first we install the patch, then we renew the certificates, and only then we change the passwords (in that order). Subject journalists should concentrate on this, and all panic moods should be completely eliminated. Observe the factual accuracy when discussing the problem, offer readers ways to check (whether they may become a victim of a vulnerability), for example, talk about existing software tools, such as Server Tester from SSL Labs, and do not forget to tell how you can get rid of the problem.