Too few people pay attention to this economic trend.

- Transfer

Translation of the Bill Gates article

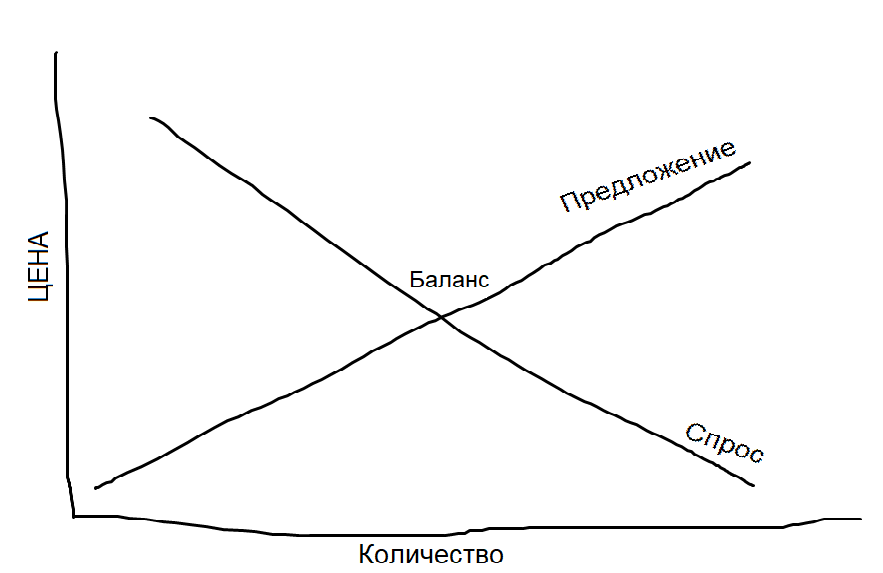

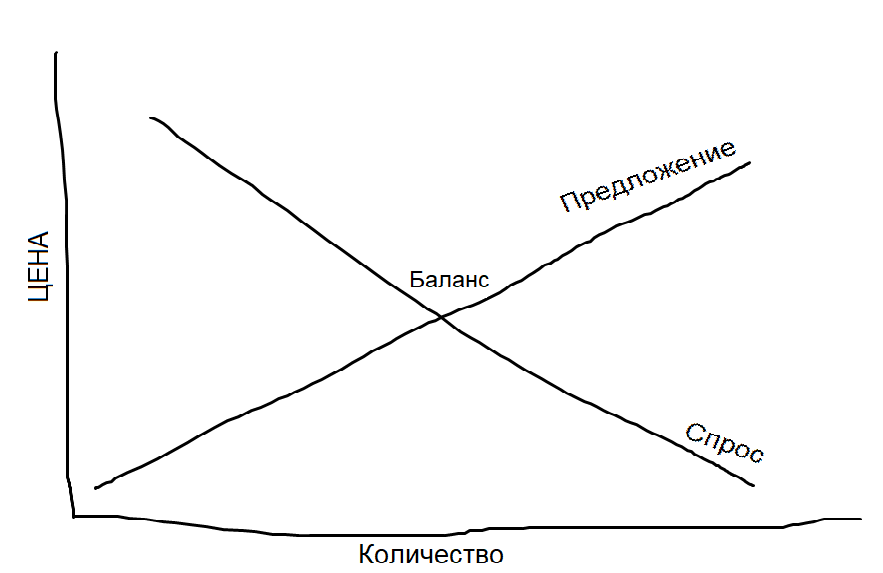

To the second semester of my first year at Harvard, I began to attend a course that I did not enroll, and practically stopped taking classes in courses I was enrolled in — apart from the course of introducing Ec 10 into economics. I was very interested in this topic, and the teacher was wonderful. One of the first things he told us was the supply and demand chart. The global economy worked like this when I was in college (and that was so many years ago that I don’t like to admit how long ago it was):

Based on this graph, two assumptions can be made. The first is more or less working today: with an increase in the demand for a product, the supply rises, and the price falls. If the price is too high, the request falls. The ideal point at which two lines intersect is called equilibrium. Balance is a magical thing, for it maximizes the benefits to society. Goods are available, there are many of them and there is profit from them. All win.

The second assumption is that the total cost of production increases with increasing supply. Imagine that Ford is releasing a new car model. The creation of the first car takes more money, since it is necessary to spend money on development and testing. But for each subsequent car you need to spend a certain amount of materials and labor. The assembly of the tenth car is the same as the assembly of the thousandth. The same is true for other things that dominated the global economy for most of the 20th century, including agriculture and real estate.

Software doesn't work that way. Microsoft can spend a lot of money on the production of the first copy of the new program, but practically nothing is spent on the production of each subsequent one. Unlike products that drove our economy in the past, software is an intangible asset. And software is not the only example: there is more data, insurance, e-books and even movies.

The part of the global economy that does not fit into the old model continues to grow. And it seriously affects everything, from tax laws to economic policy, which cities thrive and which lag behind, but in general, the rules governing the economy do not keep up with reality. This is one of the largest trends in the global economy, to which few people pay attention.

If you want to understand why this matters, then the best explanation I've ever seen is to choose the book Capitalism Without Capital written by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake. They begin with the definition of intangible assets as “something that cannot be touched.” It sounds obvious - but this is an important difference, because the industry of the intangible works differently than the industry of the tangible. Products that cannot be touched have a completely different dynamic in the sense of competition, risk, and evaluation of the companies producing them.

Haskell and Westlake identify four reasons why intangible investments behave differently:

None of these properties is good or bad in itself. They are simply different from the way industrial products work.

Haskell and Westlake explain it all — the book resembles a textbook without lengthy comments. They do not refer to this tendency as something bad, and they do not give rigid recommendations. They just slowly try to convince the reader why this transition matters, and offer general ideas about what countries could do to keep up with the world in which the Ec 10 supply and demand scheme has less and less significance.

The book opens its eyes to this topic, but it is not for everyone. Although Haskell and Westlake are well able to explain, in order to understand their reasoning, some familiarity with economics is required. If you have taken an economic course or regularly read the financial section of the Economist magazine, you will have no problems understanding their arguments.

The book convinced me even more that lawmakers must correct their economic policies so that they reflect the new reality. For example, the tools that many countries use to measure intangible assets lag behind reality, so they get an incomplete picture of the economy. The United States did not take software into account when calculating GDP before 1999. And even today, GDP does not take into account investments in such things as market research, branding and training — intangible assets that companies spend a lot of money on.

We are lagging behind not only in the field of measurement - there are a lot of big questions on which many countries should lead discussions. Are trademark and patent laws too rigid, or too soft? Is there a need to update competition policy? How to change the system of tax collection, and whether? What is the best way to stimulate the economy in a world where capitalism occurs without capital? We need very bright minds and brilliant economists to rummage in these matters. “Capitalism without capital” is the first book, from all that I have seen, that digs deep into these questions, and I think that the people who determine the policy must read it.

It took time for the investment world to take over companies built on intangible assets. At the dawn of Microsoft, it seemed to me that I was explaining to people about something completely alien to them. Our business plan did not use the asset valuation method that investors are used to. They could not imagine how much profit we can see in the long run.

Today it is difficult to imagine that someone needs to be convinced that software is a reasonable investment item, but much has changed since the 1980s. It's time to change our understanding of the economy.

To the second semester of my first year at Harvard, I began to attend a course that I did not enroll, and practically stopped taking classes in courses I was enrolled in — apart from the course of introducing Ec 10 into economics. I was very interested in this topic, and the teacher was wonderful. One of the first things he told us was the supply and demand chart. The global economy worked like this when I was in college (and that was so many years ago that I don’t like to admit how long ago it was):

Based on this graph, two assumptions can be made. The first is more or less working today: with an increase in the demand for a product, the supply rises, and the price falls. If the price is too high, the request falls. The ideal point at which two lines intersect is called equilibrium. Balance is a magical thing, for it maximizes the benefits to society. Goods are available, there are many of them and there is profit from them. All win.

The second assumption is that the total cost of production increases with increasing supply. Imagine that Ford is releasing a new car model. The creation of the first car takes more money, since it is necessary to spend money on development and testing. But for each subsequent car you need to spend a certain amount of materials and labor. The assembly of the tenth car is the same as the assembly of the thousandth. The same is true for other things that dominated the global economy for most of the 20th century, including agriculture and real estate.

Software doesn't work that way. Microsoft can spend a lot of money on the production of the first copy of the new program, but practically nothing is spent on the production of each subsequent one. Unlike products that drove our economy in the past, software is an intangible asset. And software is not the only example: there is more data, insurance, e-books and even movies.

The part of the global economy that does not fit into the old model continues to grow. And it seriously affects everything, from tax laws to economic policy, which cities thrive and which lag behind, but in general, the rules governing the economy do not keep up with reality. This is one of the largest trends in the global economy, to which few people pay attention.

If you want to understand why this matters, then the best explanation I've ever seen is to choose the book Capitalism Without Capital written by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake. They begin with the definition of intangible assets as “something that cannot be touched.” It sounds obvious - but this is an important difference, because the industry of the intangible works differently than the industry of the tangible. Products that cannot be touched have a completely different dynamic in the sense of competition, risk, and evaluation of the companies producing them.

Haskell and Westlake identify four reasons why intangible investments behave differently:

- Non-refundable costs. If your investment is not played, you do not have physical assets, such as machine tools that could be sold, returning some of the money.

- The tendency to the effect of overflow, which can take advantage of competitors. Uber's strongest side is its network of drivers, but you can often find a Uber driver who drives up Lyft customers.

- Greater scalability compared to physical assets. After the initial expenditure on the first copy, products can be propagated infinitely almost for free.

- High probability of occurrence of valuable synergistic effects together with other intangible assets. For example, Haskell and Westlake use iPod: it combined the Apple MP3 protocol [only this format, and it was not developed by Apple / approx. trans.], miniature hard drive, design skills and licensing agreements with music labels.

None of these properties is good or bad in itself. They are simply different from the way industrial products work.

Haskell and Westlake explain it all — the book resembles a textbook without lengthy comments. They do not refer to this tendency as something bad, and they do not give rigid recommendations. They just slowly try to convince the reader why this transition matters, and offer general ideas about what countries could do to keep up with the world in which the Ec 10 supply and demand scheme has less and less significance.

The book opens its eyes to this topic, but it is not for everyone. Although Haskell and Westlake are well able to explain, in order to understand their reasoning, some familiarity with economics is required. If you have taken an economic course or regularly read the financial section of the Economist magazine, you will have no problems understanding their arguments.

The book convinced me even more that lawmakers must correct their economic policies so that they reflect the new reality. For example, the tools that many countries use to measure intangible assets lag behind reality, so they get an incomplete picture of the economy. The United States did not take software into account when calculating GDP before 1999. And even today, GDP does not take into account investments in such things as market research, branding and training — intangible assets that companies spend a lot of money on.

We are lagging behind not only in the field of measurement - there are a lot of big questions on which many countries should lead discussions. Are trademark and patent laws too rigid, or too soft? Is there a need to update competition policy? How to change the system of tax collection, and whether? What is the best way to stimulate the economy in a world where capitalism occurs without capital? We need very bright minds and brilliant economists to rummage in these matters. “Capitalism without capital” is the first book, from all that I have seen, that digs deep into these questions, and I think that the people who determine the policy must read it.

It took time for the investment world to take over companies built on intangible assets. At the dawn of Microsoft, it seemed to me that I was explaining to people about something completely alien to them. Our business plan did not use the asset valuation method that investors are used to. They could not imagine how much profit we can see in the long run.

Today it is difficult to imagine that someone needs to be convinced that software is a reasonable investment item, but much has changed since the 1980s. It's time to change our understanding of the economy.