Five pitfalls when using shared_ptr

The shared_ptr class is a convenient tool that can solve many developer problems. However, in order not to make mistakes, you need to know his device perfectly. I hope my article will be useful to those who are just starting to work with this tool.

I will talk about the following:

The described problems occur both for boost :: shared_ptr and for std :: shared_ptr. At the end of the article you will find an application with full texts of programs written to demonstrate the described features (using the boost library as an example).

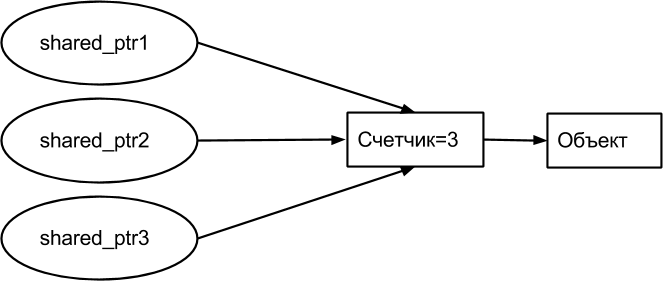

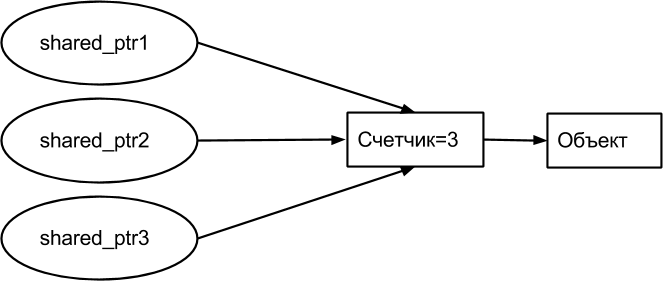

This problem is the most famous and is due to the fact that the shared_ptr pointer is based on reference counting. For an instance of the object owned by shared_ptr, a counter is created. This counter is common to all shared_ptr pointing to this object.

When constructing a new object, an object with a counter is created and the value 1 is placed in it. When copying, the counter is increased by 1. When the destructor is called (or when the pointer is replaced by assignment, or by calling reset), the counter decreases by 1.

Consider an example:

What happens when objects a and b leave the scope? In the destructor, references to objects will decrease. Each object will have a counter = 1 (after all, a still points to b, and b to a). Objects “hold” each other and our application does not have the opportunity to access them - these objects are “lost”.

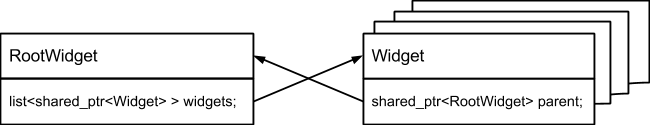

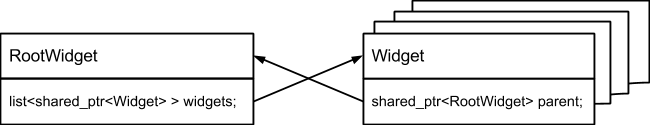

There is weak_ptr to solve this problem. One of the typical cases of creating cross-references is when one object owns a collection of other objects

With such a device, each Widget will prevent the removal of RootWidget and vice versa.

In this case, you need to answer the question: “Who owns whom?”. Obviously, it is RootWidget in this case that owns Widget objects, and not vice versa. Therefore, you need to modify the example like this:

Weak links do not prevent the removal of an object. They can be converted to strengths in two ways:

1) The shared_ptr constructor

2) lock method

Conclusion:

In the case of circular links in the code, use weak_ptr to solve the problems.

The problem of nameless pointers refers to the issue of “sequence points”

Of these two options, the documentation recommends that you always use the second - give the names names. Consider an example where the bar function is defined like this:

The fact is that in the first case, the design order is not defined. It all depends on the particular compiler and compilation flags. For example, this could happen like this:

Surely you can only be sure that calling foo will be the last action, and shared_ptr will be constructed after creating the object (new Widget). However, there are no guarantees that it will be constructed immediately after the creation of the object.

If an exception is thrown during the second step (and it will be thrown in our example), then Widget will be considered constructed, but shared_ptr will not yet own it. As a result, the link to this object will be lost. I tested this example on gcc 4.7.2. The order of the call was such that shared_ptr + new, regardless of the compilation options, were not separated by a call to bar. But rely on just such behavior is not worth it - it is not guaranteed. I would be grateful if they tell me the compiler, its version and compilation options for which such code will lead to an error.

Another way to get around the anonymous shared_ptr problem is to use the make_shared or allocate_shared functions. For our example, it will look like this:

This example looks even more concise than the original one, and also has a number of advantages in terms of memory allocation (we will leave efficiency issues outside the article). Let's make_shared call with any number of arguments. For example, the following code will return shared_ptr to a string created through a constructor with one parameter.

Conclusion:

Give shared_ptr names, even if the code is less concise, or use the

make_shared and allocate_shared functions to create objects .

Link counting in shared_ptr is built using an atomic counter. We safely use pointers to the same object from different threads. In any case, we are not used to worrying about reference counting (thread safety of the object itself is another problem).

Let's say we have a global shared_ptr:

Run the read call from different threads and you will see that there are no problems in the code (as long as you perform thread-safe operations for this class on Widget).

Suppose there is another function:

The shared_ptr device is quite complicated, so I will provide code that schematically helps show the problem. Of course, this code looks different.

Let's say the first thread starts copying globalSharedPtr (read), and the second thread calls reset for the same pointer instance (write). The result may be the following:

Or it may be that stream1 on line A2 has time to increment the counter before stream2 causes objects to be deleted, but after stream2 has counted down. Then we get a new shared_ptr pointing to the remote counter and object.

You can write similar code:

Now, using such functions, you can safely work with this shared_ptr.

Conclusion: if some shared_ptr instance is available to different threads and can be modified, then you need to take care of synchronizing access to this shared_ptr instance.

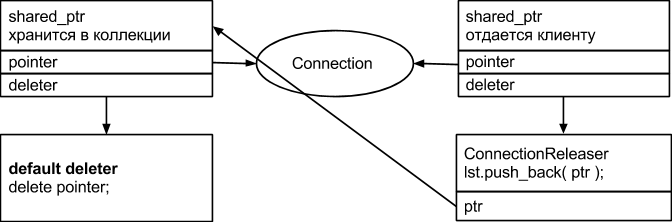

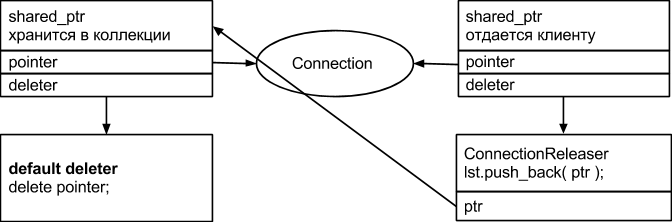

This problem can only occur if you use your own release functor in combination with weak pointers (weak_ptr). For example, you can create shared_ptr based on another shared_ptr by adding a new action before deletion (essentially the “Decorator” template). So you could get a pointer to work with the database by removing it from the connection pool, and when the client finishes working with the pointer, return it back to the pool.

The problem is that the object passed as the release functor for shared_ptr will be destroyed only when all references to the object are destroyed - both strong (shared_ptr) and weak (weak_ptr). Thus, if ConnectionReleaser does not take care to “release” the pointer passed to it (connectionToRelease), it will keep a strong link as long as there is at least one weak_ptr from shared_ptr created by the getConnection function. This can lead to quite unpleasant and unexpected behavior of your application.

It is also possible that you use bind to create a release functor. For example, like this:

Remember that bind copies the arguments passed to it (except for the case using boost :: ref), and if there is shared_ptr among them, then it should also be cleared in order to avoid the problem already described.

Conclusion: Perform in the release function all the actions that must be performed when breaking the last strong link. Reset all shared_ptr, which for some reason are members of your functor. If you use bind, then do not forget that it copies the arguments passed to it.

Sometimes you need to get shared_ptr from the methods of the object itself. Trying to create a new shared_ptr from this will lead to undefined behavior (most likely to crash the program), unlike intrusive_ptr, for which this is common practice. To solve this problem, a template-impurity class enable_shared_from_this was invented.

The enable_shared_from_this template is structured as follows: the class contains weak_ptr, which, when constructing shared_ptr, contains a reference to this shared_ptr. When the object's shared_from_this method is called, weak_ptr is converted to shared_ptr through the constructor. Schematically, the template looks like this:

The shared_ptr constructor for this case looks like this:

It is important to understand that when constructing the weak_this_ object, it still does not indicate anything. The correct link will appear in it only after the constructed object is passed to the shared_ptr constructor. Any attempt to call shared_from_this from the constructor will throw a bad_weak_ptr exception.

An attempt to access shared_from_this from the destructor will lead to the same consequences, but for a different reason: at the time of the destruction of the object, it is already believed that no strong links point to it (the counter is decremented).

With the second case (destructor), little can be thought of. The only option is to take care not to call shared_from_this and make sure that the functions that the destructor calls do not.

The first case is a bit simpler. Surely you have already decided that the only way for your object to exist is shared_ptr, then it will be appropriate to move the constructor of the object to the private part of the class and create a static method to create the shared_ptr of the type you need. If during the initialization of the object you need to perform actions that require shared_from_this, then for this purpose you can select the logic in the init method.

Conclusion:

Avoid calls (direct or indirect) to shared_from_this from constructors and destructors. If proper initialization of the object requires access to shared_from_this: create the init method, delegate the creation of the object to the static method and make it so that objects can only be created using this method.

The article discusses 5 features of using shared_ptr and provides general recommendations for avoiding potential problems.

Although shared_ptr removes a lot of problems from the developer, knowledge of the internal device (albeit approximately) is mandatory for the proper use of shared_ptr. I recommend that you carefully study the shared_ptr device, as well as the classes associated with it. Compliance with a number of simple rules can save the developer from unwanted problems.

The appendix contains the full texts of the programs to illustrate the cases described in the article.

I will talk about the following:

- What are cross references

- what are dangerous nameless shared_ptr;

- what dangers await when using shared_ptr in a multi-threaded environment;

- what is important to remember when creating your own release function for shared_ptr;

- what are the features of using the enable_shared_from_this template.

The described problems occur both for boost :: shared_ptr and for std :: shared_ptr. At the end of the article you will find an application with full texts of programs written to demonstrate the described features (using the boost library as an example).

Cross reference

This problem is the most famous and is due to the fact that the shared_ptr pointer is based on reference counting. For an instance of the object owned by shared_ptr, a counter is created. This counter is common to all shared_ptr pointing to this object.

When constructing a new object, an object with a counter is created and the value 1 is placed in it. When copying, the counter is increased by 1. When the destructor is called (or when the pointer is replaced by assignment, or by calling reset), the counter decreases by 1.

Consider an example:

struct Widget {

shared_ptr otherWidget;

};

void foo() {

shared_ptr a(new Widget);

shared_ptr b(new Widget);

a->otherWidget = b;

// В этой точке у второго объекта счетчик ссылок = 2

b->otherWidget = a;

// В этой точке у обоих объектов счетчик ссылок = 2

}

What happens when objects a and b leave the scope? In the destructor, references to objects will decrease. Each object will have a counter = 1 (after all, a still points to b, and b to a). Objects “hold” each other and our application does not have the opportunity to access them - these objects are “lost”.

There is weak_ptr to solve this problem. One of the typical cases of creating cross-references is when one object owns a collection of other objects

struct RootWidget {

list > widgets;

};

struct Widget {

shared_ptr parent;

};

With such a device, each Widget will prevent the removal of RootWidget and vice versa.

In this case, you need to answer the question: “Who owns whom?”. Obviously, it is RootWidget in this case that owns Widget objects, and not vice versa. Therefore, you need to modify the example like this:

struct Widget {

weak_ptr parent;

};

Weak links do not prevent the removal of an object. They can be converted to strengths in two ways:

1) The shared_ptr constructor

weak_ptr w = …;

// В случае, если объект уже удален, в конструкторе shared_ptr будет сгенерировано исключение

shared_ptr p( w );

2) lock method

weak_ptr w = …;

// В случае, если объект уже удален, то p будет пустым указателем

if( shared_ptr p = w.lock() ) {

// Объект не был удален – с ним можно работать

}

Conclusion:

In the case of circular links in the code, use weak_ptr to solve the problems.

Unnamed pointers

The problem of nameless pointers refers to the issue of “sequence points”

// shared_ptr, который передается в функцию foo - безымянный

foo( shared_ptr(new Widget), bar() );

// shared_ptr, который передается в функцию foo имеет имя p

shared_ptr p(new Widget);

foo( p, bar() );

Of these two options, the documentation recommends that you always use the second - give the names names. Consider an example where the bar function is defined like this:

int bar() {

throw std::runtime_error(“Exception from bar()”);

}

The fact is that in the first case, the design order is not defined. It all depends on the particular compiler and compilation flags. For example, this could happen like this:

- new widget

- bar function call

- shared_ptr construction

- foo function call

Surely you can only be sure that calling foo will be the last action, and shared_ptr will be constructed after creating the object (new Widget). However, there are no guarantees that it will be constructed immediately after the creation of the object.

If an exception is thrown during the second step (and it will be thrown in our example), then Widget will be considered constructed, but shared_ptr will not yet own it. As a result, the link to this object will be lost. I tested this example on gcc 4.7.2. The order of the call was such that shared_ptr + new, regardless of the compilation options, were not separated by a call to bar. But rely on just such behavior is not worth it - it is not guaranteed. I would be grateful if they tell me the compiler, its version and compilation options for which such code will lead to an error.

Another way to get around the anonymous shared_ptr problem is to use the make_shared or allocate_shared functions. For our example, it will look like this:

foo( make_shared(), bar() );

This example looks even more concise than the original one, and also has a number of advantages in terms of memory allocation (we will leave efficiency issues outside the article). Let's make_shared call with any number of arguments. For example, the following code will return shared_ptr to a string created through a constructor with one parameter.

make_shared("shared string");

Conclusion:

Give shared_ptr names, even if the code is less concise, or use the

make_shared and allocate_shared functions to create objects .

The problem of using in different threads

Link counting in shared_ptr is built using an atomic counter. We safely use pointers to the same object from different threads. In any case, we are not used to worrying about reference counting (thread safety of the object itself is another problem).

Let's say we have a global shared_ptr:

shared_ptr globalSharedPtr(new Widget);

void read() {

shared_ptr x = globalSharedPtr;

// Сделать что-нибудь с Widget

}

Run the read call from different threads and you will see that there are no problems in the code (as long as you perform thread-safe operations for this class on Widget).

Suppose there is another function:

void write() {

globalSharedPtr.reset( new Widget );

}

The shared_ptr device is quite complicated, so I will provide code that schematically helps show the problem. Of course, this code looks different.

shared_ptr::shared_ptr(const shared_ptr& x) {

A1: pointer = x.pointer;

A2: counter = x.counter;

A3: atomic_increment( *counter );

}

shared_ptr::reset(T* newObject) {

B1: if( atomic_decrement( *counter ) == 0 ) {

B2: delete pointer;

B3: delete counter;

B4: }

B5: pointer = newObject;

B6: counter = new Counter;

}

Let's say the first thread starts copying globalSharedPtr (read), and the second thread calls reset for the same pointer instance (write). The result may be the following:

- Thread1 has just completed line A2, but has not yet moved to line A3 (atomic increment).

- Stream2 at this time reduced the counter on line B1, saw that after decreasing the counter became zero and completed lines B2 and B3.

- Thread1 reaches line A3 and tries to atomically increase the counter, which is already gone.

Or it may be that stream1 on line A2 has time to increment the counter before stream2 causes objects to be deleted, but after stream2 has counted down. Then we get a new shared_ptr pointing to the remote counter and object.

You can write similar code:

shared_ptr globalSharedPtr(new Widget);

mutex_t globalSharedPtrMutex;

void resetGlobal(Widget* x) {

write_lock_t l(globalSharedPtrMutex);

globalSharedPtr.reset( x );

}

shared_ptr getGlobal() {

read_lock_t l(globalSharedPtrMutex);

return globalSharedPtr;

}

void read() {

shared_ptr x = getGlobal();

// Вот с этим x теперь можно работать

}

void write() {

resetGlobal( new Widget );

}

Now, using such functions, you can safely work with this shared_ptr.

Conclusion: if some shared_ptr instance is available to different threads and can be modified, then you need to take care of synchronizing access to this shared_ptr instance.

Features of the destruction time of the release functor for shared_ptr

This problem can only occur if you use your own release functor in combination with weak pointers (weak_ptr). For example, you can create shared_ptr based on another shared_ptr by adding a new action before deletion (essentially the “Decorator” template). So you could get a pointer to work with the database by removing it from the connection pool, and when the client finishes working with the pointer, return it back to the pool.

typedef shared_ptr ptr_t;

class ConnectionReleaser {

list& whereToReturn;

ptr_t connectionToRelease;

public:

ConnectionReleaser(list& lst, const ptr_t& x):whereToReturn(lst), connectionToRelease(x) {}

void operator()(Connection*) {

whereToReturn.push_back( connectionToRelease );

// Обратите внимание на следующую строчку

connectionToRelease.reset();

}

};

ptr_t getConnection() {

ptr_t c( connectionList.back() );

connectionList.pop_back();

ptr_t r( c.get(), ConnectionReleaser( connectionList, c ) );

return r;

}

The problem is that the object passed as the release functor for shared_ptr will be destroyed only when all references to the object are destroyed - both strong (shared_ptr) and weak (weak_ptr). Thus, if ConnectionReleaser does not take care to “release” the pointer passed to it (connectionToRelease), it will keep a strong link as long as there is at least one weak_ptr from shared_ptr created by the getConnection function. This can lead to quite unpleasant and unexpected behavior of your application.

It is also possible that you use bind to create a release functor. For example, like this:

void releaseConnection(std::list& whereToReturn, ptr_t& connectionToRelease) {

whereToReturn.push_back( connectionToRelease );

// Обратите внимание на следующую строчку

connectionToRelease.reset();

}

ptr_t getConnection() {

ptr_t c( connectionList.back() );

connectionList.pop_back();

ptr_t r( c.get(), boost::bind(&releaseConnection, boost::ref(connectionList), c) );

return r;

}

Remember that bind copies the arguments passed to it (except for the case using boost :: ref), and if there is shared_ptr among them, then it should also be cleared in order to avoid the problem already described.

Conclusion: Perform in the release function all the actions that must be performed when breaking the last strong link. Reset all shared_ptr, which for some reason are members of your functor. If you use bind, then do not forget that it copies the arguments passed to it.

Features of working with the enable_shared_from_this template

Sometimes you need to get shared_ptr from the methods of the object itself. Trying to create a new shared_ptr from this will lead to undefined behavior (most likely to crash the program), unlike intrusive_ptr, for which this is common practice. To solve this problem, a template-impurity class enable_shared_from_this was invented.

The enable_shared_from_this template is structured as follows: the class contains weak_ptr, which, when constructing shared_ptr, contains a reference to this shared_ptr. When the object's shared_from_this method is called, weak_ptr is converted to shared_ptr through the constructor. Schematically, the template looks like this:

template

class enable_shared_from_this {

weak_ptr weak_this_;

public:

shared_ptr shared_from_this() {

// Преобразование слабой ссылки в сильную через конструктор shared_ptr

shared_ptr p( weak_this_ );

return p;

}

};

class Widget: public enable_shared_from_this {};

The shared_ptr constructor for this case looks like this:

shared_ptr::shared_ptr(T* object) {

pointer = object;

counter = new Counter;

object->weak_this_ = *this;

}

It is important to understand that when constructing the weak_this_ object, it still does not indicate anything. The correct link will appear in it only after the constructed object is passed to the shared_ptr constructor. Any attempt to call shared_from_this from the constructor will throw a bad_weak_ptr exception.

struct BadWidget: public enable_shared_from_this {

BadWidget() {

// При вызове shared_from_this() будет сгенерировано bad_weak_ptr

cout << shared_from_this() << endl;

}

};

An attempt to access shared_from_this from the destructor will lead to the same consequences, but for a different reason: at the time of the destruction of the object, it is already believed that no strong links point to it (the counter is decremented).

struct BadWidget: public enable_shared_from_this {

~BadWidget() {

// При вызове shared_from_this() будет сгенерировано bad_weak_ptr

cout << shared_from_this() << endl;

}

};

With the second case (destructor), little can be thought of. The only option is to take care not to call shared_from_this and make sure that the functions that the destructor calls do not.

The first case is a bit simpler. Surely you have already decided that the only way for your object to exist is shared_ptr, then it will be appropriate to move the constructor of the object to the private part of the class and create a static method to create the shared_ptr of the type you need. If during the initialization of the object you need to perform actions that require shared_from_this, then for this purpose you can select the logic in the init method.

class GoodWidget: public enable_shared_from_this {

void init() {

cout << shared_from_this() << endl;

}

public:

static shared_ptr create() {

shared_ptr p(new GoodWidget);

p->init();

return p;

}

};

Conclusion:

Avoid calls (direct or indirect) to shared_from_this from constructors and destructors. If proper initialization of the object requires access to shared_from_this: create the init method, delegate the creation of the object to the static method and make it so that objects can only be created using this method.

Conclusion

The article discusses 5 features of using shared_ptr and provides general recommendations for avoiding potential problems.

Although shared_ptr removes a lot of problems from the developer, knowledge of the internal device (albeit approximately) is mandatory for the proper use of shared_ptr. I recommend that you carefully study the shared_ptr device, as well as the classes associated with it. Compliance with a number of simple rules can save the developer from unwanted problems.

Literature

- Boost.org documentation

- Scott Meyers “More Effective C ++: 35 New Ways to Improve Your Programs and Designs”

application

The appendix contains the full texts of the programs to illustrate the cases described in the article.

Ring Link Issue Demonstration

#include

#include

#include

#include

class BadWidget {

std::string name;

boost::shared_ptr otherWidget;

public:

BadWidget(const std::string& n):name(n) {

std::cout << "BadWidget " << name << std::endl;

}

~BadWidget() {

std::cout << "~BadWidget " << name << std::endl;

}

void setOther(const boost::shared_ptr& x) {

otherWidget = x;

std::cout << name << " now points to " << x->name << std::endl;

}

};

class GoodWidget {

std::string name;

boost::weak_ptr otherWidget;

public:

GoodWidget(const std::string& n):name(n) {

std::cout << "GoodWidget " << name << std::endl;

}

~GoodWidget() {

std::cout << "~GoodWidget " << name << std::endl;

}

void setOther(const boost::shared_ptr& x) {

otherWidget = x;

std::cout << name << " now points to " << x->name << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

{ // В этом примере происходит утечка памяти

std::cout << "====== Example 3" << std::endl;

boost::shared_ptr w1(new BadWidget("3_First"));

boost::shared_ptr w2(new BadWidget("3_Second"));

w1->setOther( w2 );

w2->setOther( w1 );

}

{ // А в этом примере использован weak_ptr и утечки памяти не происходит

std::cout << "====== Example 3" << std::endl;

boost::shared_ptr w1(new GoodWidget("4_First"));

boost::shared_ptr w2(new GoodWidget("4_Second"));

w1->setOther( w2 );

w2->setOther( w1 );

}

return 0;

}

Demonstration of converting weak_ptr to shared_ptr

#include

#include

#include

class Widget {};

int main() {

boost::weak_ptr w;

// В этой точке weak_ptr ни на что не указывает

// Метод lock вернет пустой указатель

std::cout << __LINE__ << ": " << w.lock().get() << std::endl;

// Конструирование shared_ptr от этого указателя приведет к исключению

try {

boost::shared_ptr tmp ( w );

} catch (const boost::bad_weak_ptr&) {

std::cout << __LINE__ << ": bad_weak_ptr" << std::endl;

}

boost::shared_ptr p(new Widget);

// Теперь у weak_ptr есть значение

w = p;

// Метод lock вернет правильный указатель

std::cout << __LINE__ << ": " << w.lock().get() << std::endl;

// Конструирование shared_ptr от этого указателя тоже вернет правильный указатель. Исключения не будет

std::cout << __LINE__ << ": " << boost::shared_ptr( w ).get() << std::endl;

// Сбросим указатель

p.reset();

// Сильных ссылок больше нет. У weak_ptr истек срок годности

// Метод lock снова вернет пустой указатель

std::cout << __LINE__ << ": " << w.lock().get() << std::endl;

// Конструирование shared_ptr от этого указателя снова приведет к исключению

try {

boost::shared_ptr tmp ( w );

} catch (const boost::bad_weak_ptr&) {

std::cout << __LINE__ << ": bad_weak_ptr" << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

Demonstration of multithreading problem for shared_ptr

#include

#include

#include

typedef boost::shared_mutex mutex_t;

typedef boost::unique_lock read_lock_t;

typedef boost::shared_lock write_lock_t;

mutex_t globalMutex;

boost::shared_ptr globalPtr(new int(0));

const int readThreads = 10;

const int maxOperations = 10000;

boost::shared_ptr getPtr() {

// Закомментируйте следующую строку, чтобы ваше приложение упало

read_lock_t l(globalMutex);

return globalPtr;

}

void resetPtr(const boost::shared_ptr& x) {

// Закомментируйте следующую строку, чтобы ваше приложение упало

write_lock_t l(globalMutex);

globalPtr = x;

}

void myRead() {

for(int i = 0; i < maxOperations; ++i) {

boost::shared_ptr p = getPtr();

}

}

void myWrite() {

for(int i = 0; i < maxOperations; ++i) {

resetPtr( boost::shared_ptr( new int(i)) );

}

}

int main() {

boost::thread_group tg;

tg.create_thread( &myWrite );

for(int i = 0; i < readThreads; ++i) {

tg.create_thread( &myRead );

}

tg.join_all();

return 0;

}

Demonstration of deleter + weak_ptr problem

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

class Connection {

std::string name;

public:

const std::string& getName() const { return name; }

explicit Connection(const std::string& n):name(n) {

std::cout << "Connection " << name << std::endl;

}

~Connection() {

std::cout << "~Connection " << name << std::endl;

}

};

typedef boost::shared_ptr ptr_t;

class ConnectionPool {

std::list connections;

// Этот класс предназначен для демонстрации первого варианта создания deleter (get1)

class ConnectionReleaser {

std::list& whereToReturn;

ptr_t connectionToRelease;

public:

ConnectionReleaser(std::list& lst, const ptr_t& x):whereToReturn(lst), connectionToRelease(x) {}

void operator()(Connection*) {

whereToReturn.push_back( connectionToRelease );

std::cout << "get1: Returned connection " << connectionToRelease->getName() << " to the list" << std::endl;

// Закомментируйте след. строку и обратите внимание на разницу в выходной печати

connectionToRelease.reset();

}

};

// Эта функция предназначена для демонстрации второго варианта создания deleter (get2)

static void releaseConnection(std::list& whereToReturn, ptr_t& connectionToRelease) {

whereToReturn.push_back( connectionToRelease );

std::cout << "get2: Returned connection " << connectionToRelease->getName() << " to the list" << std::endl;

// Закомментируйте следующую строку и обратите внимание на разницу в выходной печати

connectionToRelease.reset();

}

ptr_t popConnection() {

if( connections.empty() ) throw std::runtime_error("No connections left");

ptr_t w( connections.back() );

connections.pop_back();

return w;

}

public:

ptr_t get1() {

ptr_t w = popConnection();

std::cout << "get1: Taken connection " << w->getName() << " from list" << std::endl;

ptr_t r( w.get(), ConnectionReleaser( connections, w ) );

return r;

}

ptr_t get2() {

ptr_t w = popConnection();

std::cout << "get2: Taken connection " << w->getName() << " from list" << std::endl;

ptr_t r( w.get(), boost::bind(&releaseConnection, boost::ref(connections), w ));

return r;

}

void add(const std::string& name) {

connections.push_back( ptr_t(new Connection(name)) );

}

ConnectionPool() {

std::cout << "ConnectionPool" << std::endl;

}

~ConnectionPool() {

std::cout << "~ConnectionPool" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

boost::weak_ptr weak1;

boost::weak_ptr weak2;

{

ConnectionPool cp;

cp.add("One");

cp.add("Two");

ptr_t p1 = cp.get1();

weak1 = p1;

ptr_t p2 = cp.get2();

weak2 = p2;

}

std::cout << "Here the ConnectionPool is out of scope, but weak_ptrs are not" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Demonstration of a problem with enable_shared_from_this

#include

#include

#include

class BadWidget1: public boost::enable_shared_from_this {

public:

BadWidget1() {

std::cout << "Constructor" << std::endl;

std::cout << shared_from_this() << std::endl;

}

};

class BadWidget2: public boost::enable_shared_from_this {

public:

~BadWidget2() {

std::cout << "Destructor" << std::endl;

std::cout << shared_from_this() << std::endl;

}

};

class GoodWidget: public boost::enable_shared_from_this {

GoodWidget() {}

void init() {

std::cout << "init()" << std::endl;

std::cout << shared_from_this() << std::endl;

}

public:

static boost::shared_ptr create() {

boost::shared_ptr p(new GoodWidget);

p->init();

return p;

}

};

int main() {

boost::shared_ptr good = GoodWidget::create();

try {

boost::shared_ptr bad1(new BadWidget1);

} catch( const boost::bad_weak_ptr&) {

std::cout << "Caught bad_weak_ptr for BadWidget1" << std::endl;

}

try {

boost::shared_ptr bad2(new BadWidget2);

// При компиляции с новым стандартом вы получите terminate

// т.к. считается, что из деструктора по умолчанию не может быть сгенерировано исключение

} catch( const boost::bad_weak_ptr&) {

std::cout << "Caught bad_weak_ptr for BadWidget2" << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}