African anthropocene

- Transfer

Anthropocene looks different depending on where you are - and too often the word "we" means white people of the western world.

Every year, as a result of human activity, more sedimentary rocks and rocks move than as a result of all natural processes on the planet combined, including erosion and river flow. This may not surprise you. You may have already met with similar statements signaling the exceptional scale of how we terraform our planet in the anthropocene era . Scientists studying natural sciences and sociology have a heated debate about everything related to the anthropocene, from the nuances of terminology to the date of the beginning of a new geological epoch, but most of them agree in the following: The Earth will outlive humanity. Doubts remain only about how long we will live on the planet and under what conditions.

But who exactly are these "we"?

Look at the cover of Nature magazine from March 2015, in which two Earths, one green-blue and the other gray, intertwined in the form of a human body. The heading, going through the press of a person, suggests us to consider this body as a representative of the human race. But there is no such thing as a generalized person; the image repeats the fusion of the concepts “man” and “white man” that has a century-long history. Perhaps the artist was trying to hide it without showing the eyes of a person, making him a blind sight, having no idea about the damage he causes to his body and his planet. However, this image promotes an idea that is often criticized when discussing the concept of anthropocene: it attributes blame for environmental collapse to a certain generalized “humanity”, although in practice responsibility and vulnerability are unevenly distributed.

Although the anthropocene leaves its traces in all our bodies every minute - we all have endocrine disruptors , microplastic and other toxins pushing through our metabolism - it manifests itself differently in different bodies. These differences and the history of their occurrence are extremely important - not only for people suffering from them, but also for the relationship of humanity with the planet.

What image of anthropocene, for example, occurs when we begin our analytical journey not in Europe, but in Africa? African minerals played a large role in stimulating colonialism and fueled industrialization. Their prey was fed by the anthropocene. And the simple statement that “we” move more rocks than all natural processes does not even come close to describing this cruel dynamic. Who specifically moved the rocks? How has this movement affected people and ecosystems around the mines, not only during the extraction of minerals, but decades later?

Africa is a complex continent with a complex history, and the answers to these questions vary depending on place and time. We begin by considering two minerals of international importance: gold and uranium. Gold, as the currency generally accepted for centuries, has become the main lubricant of industrial capitalism, supporting the state money of Europe and North America during a massive industrial expansion. Uranus fed the Cold War. Some of its decay products in power plants and weapons factories will remain radioactive for more than 100,000 years - a clear indication of the anthropocene epoch for future geologists (if any).

During the 20th century, the Witwatersrand Plateauin South Africa, better known as Rand, it supplied abundantly both types of minerals. Industrial gold mining began here in 1886. In the following century, hundreds of thousands of people moved there looking for work, digging underground tunnels deeper than anywhere else on the planet, making South Africa the largest supplier of gold in the world. Workers dragged ore to the surface through narrow, hot, poorly ventilated passages. Many died under the rubble. Tens of thousands of those who survived caught silicosis , forced to breathe dust for years. The term "anthropocene" did not exist yet, but it already left its mark on the lungs of more and more new generations of Africans.

In the first decades, much of the rock raised so hard to the surface was too poor to recoup the cost of processing. This waste was dumped near the entrances to the mines. By 1930, huge piles of slag changed the topography of the region. In July and August, the winter winds carried dust from these heaps all over the plateau and across the erratic Johannesburg. Several botanists, having seen the problem of environmental pollution by the mining industry, tried to figure out how to plant these heaps with vegetation to prevent erosion. But their attempts for decades remained without financing, and as a result they completely stopped under pressure from their opponents, representatives of industrialists. This story also became the most typical example of the development of the anthropocene.and such stories have been happening since at least the 19th century: industry deliberately pollutes the environment; Scientists investigate the extent of pollution and offer solutions; industry, often with the permission of officials, declares work to eliminate too expensive; scientists do not give money; problems are ignored.

After World War II, which was considered slag, acquired a new economic value. It contained uranium, an element whose splitting leveled down two Japanese cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki . The gold mining industry rejoiced when it discovered a new source of income. In 1952, the new government of South Africa who imposed apartheid, with great pomp, opened the first uranium mining factory. Soon, mountains of slag produced 10,000 tons of uranium oxide, exported to the United States and Britain to replenish their arsenals . Today, most of this uranium is stored in aging missiles. But during the active phase of testing nuclear weapons in the late 1950s and early 1960s, part of it exploded in the atmosphere, falling back to Earth in the form of chemicals created by decay. Today, scientists studying the planet, looking for signs of the end of the Holocene, argue that these radioactive deposits have become a " golden crutch ", marking the beginning of the anthropocene.

At least two deposits of South Africa in the anthropocene, uranium and gold, spread throughout the planet. But the impact of this contribution on South Africans is only beginning to manifest itself. Rand, permeated by hundreds of mines and tunnels, became what architect Yel Weitzman of Goldsmiths University in London calls , in a different context, “hollow ground”. And the hollow lands are unreliable. Over time, the water fills the abandoned mines, reacts with pyrite in bare stones and becomes acidic. Heavy metals, previously enclosed in conglomerates- including such well-known toxins as arsenic, mercury, lead - easily dissolve in acidified water. This toxic soup rises gradually; in many places it has already spilled out onto the surface or on the groundwater level. Thousands of people - farmers, settlers, other people without alternative sources of water - use this water for irrigation, drinking and washing. And if many mountains of slag were removed under the ground, quite a few of these mountains remain untouched and unplanted vegetation. Winter winds still blow this dust - partly radioactive, with traces of uranium - and carry it through farms, settlements and suburbs. For 14 million people in the province of Gauteng, the remains of mined ore are one of the main features of the African anthropocene.

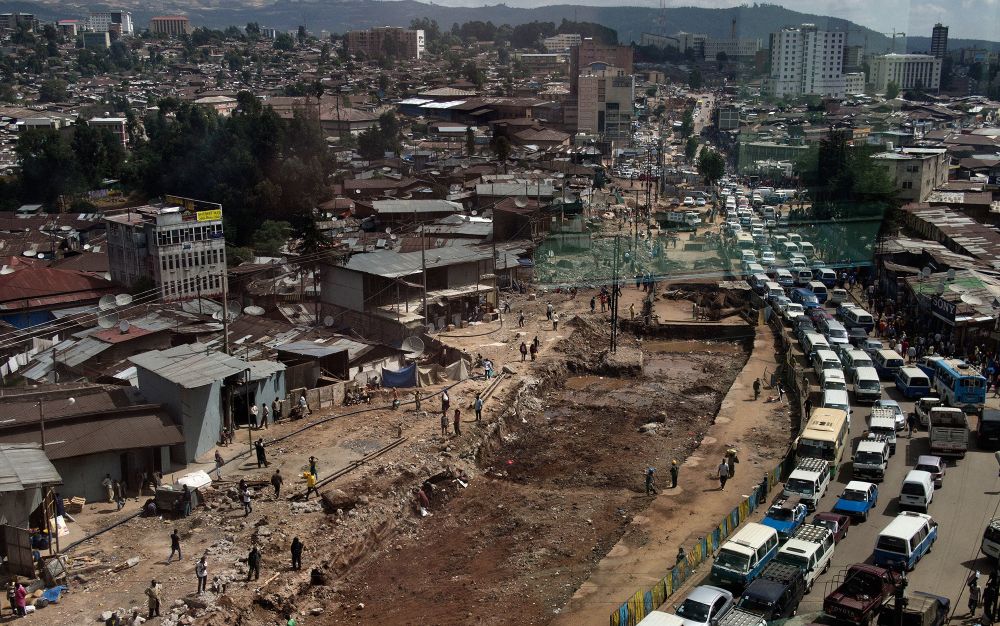

African minerals continue to feed the life that exists on the basis of industry throughout the globe, and the toxic waste from their mining annoys communities across the continent. Take the Niger Delta , one of the world's most important sources of oil. Over the past 50 years, there have been more than 7,000 spills of oil that have polluted water, land, and communities in this large region. This oil, being transformed into fuel and poured into gas tanks, makes an additional contribution to the anthropocene, which also requires attention - especially in such densely populated areas as Cairo, Dakar, Lagos and Nairobi. Residents of these cities spend many hours working and getting to work in terrible traffic jams, breathing in the fumes of diesel fuel emitted by mopeds, taxis and buses. Over the past decades, this problem has steadily worsened, following the increase in the continent’s urbanization. According to a recent report., the annual premature mortality in African cities associated with environmental pollution, from 1990 to 2013 increased by 36%; according to current estimates, it is about a quarter of a million deaths per year.

Of course, air pollution is not peculiar to urban areas of Africa. He is no less years old than British industrialization, which has been developing due to the exponential growth of coal production and combustion. Some researchers date the beginning of the anthropocene to 1750, the year when the first massive coal emissions into the atmosphere began. After 150 years, a series of picturesque images of the Palace of Westminsterwhere the British Parliament is sitting, Claude Monnet’s cyst depicted the colorful effects of these emissions, which turned into a dense smog of London in the 19th century. In 2017, the prestigious medical journal The Lancet published a report according to which environmental pollution is the leading cause of diseases associated with external factors affecting the body. Due to pollution, 9 million premature deaths occurred in 2015, and 16% of all deaths in the world - “three times more fatal cases than from HIV, tuberculosis and malaria combined, and 15 times more than from all wars and other types of violence, ”added the report. Most of these deaths occurred in low- and middle-income countries, as well as in poor communities located in rich countries.

All this should not surprise you. You have probably already seen photos of residents in Beijing and Delhi in masks, wandering through the brown-gray air. But, despite the almost equally dangerous conditions for breathing, the topic of smog in African cities is rarely covered in the media. Read the article on Wikipedia about smog : you will find there a description of cities in North and South America, Europe, Asia - but not a single mention of Africa.

Similarly, disproportionately little research is devoted to African cities. In particular, this is due to difficulties in obtaining reliable data due to the almost complete lack of infrastructure for monitoring air quality, but this is not the only reason. It is tacitly understood in the scientific community that since most of Africa is rural, air pollution there should not be a serious concern. But in Africa today there is the highest rate of urbanization in the world. Therefore, the number of victims of air pollution is also growing rapidly and this growth will accelerate. Extremely rapid urban growth exacerbates pollution problems, especially in poor countries where utilities do not keep pace with population growth. Many city dwellers inhale a toxic mixture of pollution from both the air outside the house and the air inside - the latter comes from burning wood, coal or plastic houses. This is another trace that the anthropocene leaves on African lungs.

Take Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, where in the past few years a team of researchers has been studying air pollution. They predict an increase in population from 2010 to 2020 by 81%, after which about 3.4 million people will live in the city. Most of the new inhabitants of Ouagadougou settle in informal settlements, without electricity, water or sewage. Lack of access to modern infrastructure leaves them with no choice. They have to use open fire for cooking. To earn a living, they have to navigate dirt roads, the dust of which aggravates the effects of other pollutants. The leading cause of death in Burkina Faso is a lower respiratory infection.

Ouagaduganans are not alone. Respiratory diseases and other health problems caused by suspended particles - consisting of substances such as sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and black carbon - are well known. For several years, the World Health Organization has noted environmental pollution as the most serious health problem associated with external influences on the body, the effect of which exacerbates poverty. However, as critics have pointed out, WHO does not have air quality research programs in places like Black Africa , although they do exist in Europe, in the west Pacific region and in the Americas. Although the number of scientific studies of air pollution in Africa has recently begun to grow, there are still very few of them.

Of course, urban pollution is most quickly seen and felt by those who encounter it directly. Residents of Port Harcourt in Nigeria, familiar with the smoke from oil factories and other factories that dominate their city’s economy, definitely noticed smoke getting denser and darker at the end of 2016, shrouding the city with soot. They noticed black sputum, which they coughed up in the morning, and black dust that covered their food and homes. They felt a sore throat and difficult lung function, breathing heavily on their way to work. Furious at the lack of government reaction, some residents spoke on social networks with the hashtag #StopTheSoot . Thanks to this and other forms of activism, the problem became more visible, but could not disappear.

Behind the particulars of any single case, there are systemic problems. Until recently, the neglect of air quality in African cities helped to hide an amazing fact. Diesel fumes emitted by drivers in Accra, Bamako or Dakar contain as a percentage substantially more deadly pollutants than those breathed by the people of Paris, Rome or Los Angeles.

It is not a question of consumer choice or their carelessness. This is part of a deliberate strategy for fuel traders such as Trafigura and Vitol.. These traders sell different types of fuel mixes to different countries. Using too soft restrictions on fuel quality, or their complete absence in most parts of Africa, traders maximize profits by creating high sulfur blends banned in Europe and North America. The Swiss non-profit organization Public Eye found that some blends in Africa contain up to 630 times more sulfur than European diesel. Most of the mixing takes place in the port region of Amsterdam / Rotterdam / Antwerp, but this process is so simple and cheap that they can be practiced directly on ships located on the west coast of Africa. Shamelessly, traders call these mixtures "African quality fuel" and sell them only on this continent - often to the same countries where the original oil was produced.

After this practice was promulgated by the Public Eye company in 2016, brokers pressed for the fact that they operate within the law. And there is. European limits on the sulfur content of fuels are within 10 ppm. In North America, concessions in the form of 15 parts per million are allowed. In Africa, the mean limit is 2,000; in Nigeria, the largest oil producer, it is equal to 3000. Playing on these differences, traders engage in a conventional profit maximization strategy known as “ regulatory arbitrage ”: avoiding legal restrictions in rich countries by moving industries and waste to poor.

In this case, the media attention to the problem had an impact. In November 2016, Ghana lowered the standards for sulfur content in imported fuels to 50 ppm. Amsterdam voted to ban the mixing and export of fuel, in which the percentage of pollutants exceeds the limits of the European Union. In December, the UNEP Environment Program held a meeting in Abuja, where the host country, Nigeria, and several others, announced that they would lower the sulfur limit to 50 ppm.

But sulfur is only one of many particulars. Around the world, thousands of chemicals erupt, pour out and spray in the air every day. So far, the main method of mitigation is the consideration of each individual chemical compound - the approach is difficult and in fact insufficient. In addition, enforcing restrictions is only one step. Enforcement of the rules requires a large infrastructure: government organizations, experts working in them, laboratories, monitoring networks, data processing equipment, and much more. All this costs money and puts additional pressure on limited government resources. Moreover, it would be naive to believe that companies will dutifully obey the new rules. Remember the 2015 diesel scandalin which Volkswagen caught using special "bypassing protection" devices that fake nitrogen oxide emissions in laboratory testing of cars. Other manufacturers did similar things. In the face of controlling emissions to limit anthropogenic harm, the companies that pollute the planet use, as if showing the middle finger. And in many cases it is much more than a simple engine sensor.

Regulatory arbitration is a device that bypasses the defense on a planetary scale. Oil producers are subject to more stringent restrictions on some continents, dropping dirty fuel on others. Diesel cars that do not meet European standards, are in African cities, prompting to export toxic fuels. As a result, all pollutants are in the atmosphere and affect climate change. But at the same time, some people suffer more than others. Therefore, in order to understand the consequences of the anthropocene, it is necessary to maneuver between specific places and a planetary perspective.

Some authors argue that this difference can best be reflected through a change of terminology. Capitalocent is especially popular with sociologists because it shows how global inequality and the dependence of capitalism on cheap natural resources led to the current state of affairs. Terminology has political influence; one word is capable of creating an infrastructure of reasoning leading to political change.

But words have influence only when they are generally accepted, and it is difficult to imagine that geologists or climatologists would gladly switch to alternatives. The political lever of the anthropocene concept is in its analytical potential to bring together researchers of the natural, social, and human sciences — as well as artists — to better understand the complex dynamics that represent a risk to our species.

Capitalism obviously plays an inevitable role in these historical and biophysical connections. But this is too rough and unsuitable tool for analyzing the many other processes generating these connections: hydrological patterns, radioactive particles, security measures, informal economic processes and everything else. We need sociologists and humanists, tracking the links between cars in North America and African lungs. But we need both natural scientists and doctors to describe in detail the molecular compounds that make air and water toxic for biological life. Placing these studies in the anthropocene category clarifies the links between the sufferings of the planet and individuals. It demonstrates the importance of working with both of these problems at the same time. Of course, only understanding and accepting the complexity of a topic is not enough to combat its harm. But this is a critical step.

Resistance to anthropocene, in Africa and elsewhere, requires fresh sources of imagination. They must be sought at the forefront of the transformation of the planet - from urban fighters for clean air and water to intellectuals challenging the European and North American paradigms of exploring the world. Therefore, Africa plays an important role not only in the present of our planet, but also in its future, as Cameroonian philosopher Achilles Mbembe and Senegalese economist Felvain Sarr are trying to proveand other African scientists. Africa is the continent with the highest projected population growth. There is 60% of the uncultivated arable land in the world. In some parts of Africa, advanced decentralized energy generation systems (for example, solar) are developing, possibly capable of mitigating climate change. And this is just for starters.

If the anthropocene has its place in the thoughts of people and in calls to action, it should unite people and places, and not just scientific disciplines. Above him to think, given Africa. “They” are “we”, and without them there are no planetary “us”.

Gaebriel Hecht is a professor of nuclear security at Stanford University and works at the Stanton Foundation and at the CISAC Center for International Security and Cooperation. He has authored several books that have won awards, including “Being a Nuclear Power: Africans and International Uranium Trade” (Being Nuclear: Africans and the Global Uranium Trade, 2012).