Agile team and fixed price contracts

- Transfer

Fixed price contracts are evil, that's what can be heard from agile adherents. On the other hand, such contracts are a reality that many agile teams face. But what if we try to tame this evil, and not fight it?

How can a company execute such a contract using a flexible methodology to achieve better results with less risk? In this article we will try to answer these questions.

So let's start with the contract itself.

Such contracts immediately fix three magic factors - money, time and volume of obligations. Is price and timing an issue for agile teams? Well, shouldn't be. In fact, timeboxing is a common practice. Limiting the budget only helps timeboxing work better.

The real problem with fixed price contracts is the volume of obligations, because it is usually spelled out what exactly needs to be done, instead of exactly how much we should work.

Why are customers so obsessed with a fixed amount of commitment? We understand that they want to know how much they will have to pay (and who does not want?) And when they will get the result. The only thing they don’t know is what exactly they want to receive (even if they say they know).

The roots of the problem with a fixed amount of obligations are as follows:

Each fixed price contract has an accompanying document, “Terms of Reference” or something like that. This document is designed to reduce the risks of missing out on something important and to create a common understanding of what needs to be done, which creates an illusion of predictability.

The main erroneous assumptions when fixing the volume of obligations :

Now that we understand that the main conflict between the use of flexible thinking and a fixed price contract lies in a fixed amount of obligations, we can focus on converting a fixed amount of obligations into a fixed budget.

This means that instead of providing a detailed specification of requirements, we need to focus on tracking as many requirements as possible in the form of user stories. We need to build an initial list of tasks for the product, which we will try to evaluate using the technique of difficulty points (story points) and team-wide assessment techniques, such as poker planning (Planning poker).

First, we must understand that a higher level of software granularity means completely different things for both parties to the contract. Software companies usually focus on technical details, while the other side is more focused on the financial side of the issue. Requirement specifications are usually created by software companies and are precautionary. This is where the three key players come into play.

User storiesas a way of expressing requirements, it is clear to both customers and performers. Understanding creates trust and a sense of shared vision for the project. User stories are easy to write and erase, especially if you write them on cards. They are also functional oriented, therefore they provide a clear vision of the real volume of work on the project, and we can compare them with each other in terms of time and effort.

Difficulty points(story points) as a way of evaluating stories is difficult to explain to the client at first, as this is not an ordinary way of expressing efforts. But on the other hand, they reduce the risk of underestimating the volume of obligations. How does this happen? The complexity scores are relative in nature, the focus here is either on the total volume, or on a group of stories, while the traditional assessment (usually done in man-hours) tries to analyze each function individually.

Readiness criterion(definition of done) is another method of building trust and a common understanding of processes and planning in a project. Usually, when a client first encounters user stories, even if he likes the way they are written, it is not obvious to him what the story implementation is. Teams that discuss readiness criteria with a client have a better understanding of what they expect from them. They also provide a more accurate estimate. In addition, on the client side, the availability criterion creates the conditions for a higher level of acceptance of user history.

For example, the readiness criterion for stories in a fresh web application might include the following items:

Later, the team can create other, deeper internal elements of the readiness criterion, but at the stage of preparing the contract, these general instructions give the client and the team an understanding of what we want to create within the scope of the project.

We hope that taking into account our readiness criterion, we will come to a certain value that will decompose the project budget into complexity points . And this value, and not the user stories that stand behind it, is the first thing that should be recorded in the contract. And that already opens the door to change.

Although we have a fixed amount of commitment, we still want to accept changes flexibly. We have tools (stories and difficulty scores) that you can use to compare requirements. This allows us to exchange requirements, remaining within a fixed volume of obligations. And if we can stay within this framework, then we can and fit into a fixed time frame and price.

The most difficult part of preparing a fixed price contract is determining the price and schedule, which will be fixed on the basis of a well-defined scope of obligations. Let's see what a team can bring to such a contract with a flexible initial project evaluation.

Firstly, training . Meet with the client and tell how you will work. We should tell him what user stories are, how we are going to evaluate them, and what is the readiness criterion. Often, this must be done before preparing a proposal for a client request for proposal (RFP).

The next step is to collect user stories.. It can be organized as several quick sessions in 1-2 days. This time is enough to find most of the stories that will form the vision of the product without getting deep into the jungle of functionality. From this point of view, it is very important to discuss with the client the readiness criterion for stories, iterations and releases.

We should know:

These and, probably, many more factors will influence the assessment and give a common understanding of expectations and quality on both sides. They will also help to make the assessment less optimistic, what is it if the team discusses only the technical aspects of implementing user stories.

Having discussed with the customer a set of stories and the readiness criterion, we can begin the assessment. This is a well-known part of the process. Here, the most important action is to involve as many future team members as possible so that the assessment is carried out collectively.

Techniques such as planning poker reduce the risk of underestimating a project due to the opinion of an individual team member, especially if this team member is also the most experienced, which is exactly what happens when one person is involved in the evaluation. It is also important that the stories are evaluated by people who will actually implement the system.

In fact, during the initial assessment it is often difficult to evaluate the stories using the lowest values, such as 1 and 2. The fact is that the higher the score, the less we know about the story. Therefore, scoring is easier at this initial level, because it’s much easier to say that story A is 2 times more complicated than story B than to say that story A will take 25 person-hours (remember the readiness criteria?), And story B will take 54 hours.

This works great, even if we take 3 or 5-point stories as a basic level, in which case it will be easier for us to break them into small stories already at the development stage. Beware of stories with 20, 40 or 100 points. This method of evaluation assumes that we do not know anything about what will be implemented, so we need to immediately discuss everything in more detail with the customer, and not happily enter them into the contract.

The result of the assessment is the total number of difficulty points that describe the initial amount of work to create a product. This number should be recorded as the volume of obligations under the contract, and not individual user stories.

The total number of difficulty points calculated on the basis of a set of stories does not directly give us price and time. How to get them? We need magic numbers.

Do not be surprised, because in contracts with a fixed price there are always magic numbers. All estimated values have always been such numbers. Now we are changing the way we evaluate, but in the end we still need to predict the future based on past experience. So what should we know? Predicted team performance.

Suppose we rated our stories with a total of 300 reference points. We need to determine team performance based on the following:

Suppose our team consists of 5 people - 3 programmers, 1 tester and 1 team leader - who will communicate with customers and interested parties, just like with other people outside the team (for example, Scrum Master in the Scrum methodology).

Let's say that our team will try to achieve a speed of 20 reference points in a 2-week iteration. This is our main magic number in the contract. Many factors can affect productivity during the whole time of working on a project, however, if the team we are working with is not new, and the project itself is not something completely unknown, then these numbers can be taken from past experience.

Now we may encounter one of two restrictions imposed on us by the client in the contract:

In the first scenario, we can determine the estimated completion time using the following formula:

time = (<complexity points> / <performance>) * <iteration length>

In our scenario, it will be:

time = (300 points / 20 points) * 2 weeks = 30 weeks (or 15 iterations)

If the estimated time is unacceptable, then the only thing we can change is the performance of the team. Be that as it may, the dependence is not linear, and if we double the team size, the performance will not double.

We know that the project will be completed in 20 weeks, and this is only 10 of our iterations, so we can only perform 20 points from our scope of work. Now it depends on the client what can be removed from the scope of work without losing the ability to do something that has the necessary value.

Here we can also (to some extent) resize the necessary team to increase productivity.

Knowing the required size of the team and end date, we are finally able to calculate the basic price of the contract - the cost of work:

money = <number of hours per iteration> * <number of iterations> * <people> * <the price of an hour of work>

The In our example, we get:

money = 80 hours * 15 iterations * 4 people * $ 100 = $ 480,000

Now we have the values of a fixed price contract:

These simple calculations, of course, are only part of the value that will ultimately appear in the contract, but it is also the most difficult part to determine. We wanted to show that the way we work on flexible projects can also be transferred to the contract negotiation process.

There is one more question. The client asks: “Why is it so expensive?” This is where the negotiations actually begin, and the only factor that the manufacturing company can change is the cost of a man-hour. These are the $ 100 we are negotiating about. Not the length of the iterations, not even the number of iterations. Our team has no super powers, and we will not work twice as fast if we just agree on this.

Now our contract has been signed (it was easy, right?), It’s time to create software in an agreed framework. You have probably already heard that a flexible methodology will not solve your problems, but will make them visible. Therefore, we want to know early how things are going in order to take the necessary actions. After all, there is a possibility that our magic number in the contract (our performance) was erroneous.

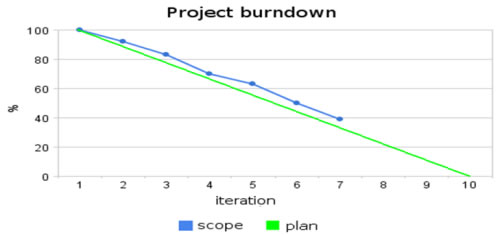

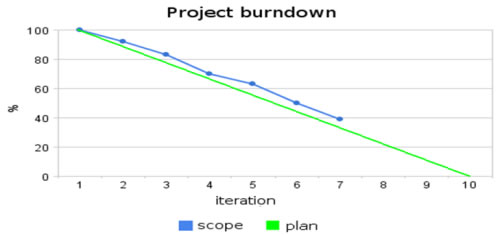

Burndown charts are a very common way to track progress in many agile projects.

They are great for visualizing planned progress and reality. For example, the burndown chart in Figure 1 looks good:

We do not fit into the plan a bit, but this does not mean that we made a big mistake in determining the performance in the process of discussing the contract. Probably many teams would want their graphics to look that way. But the problem is that this graph displays only two of the three factors - the amount of commitment and time. But what about the money?

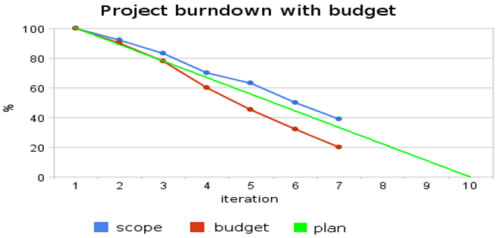

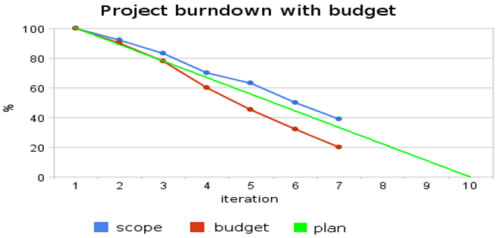

The diagram in Fig. 2 shows two scales - the amount of work and the budget. These two factors are expressed here as a percentage of good reason. After all, there is no other way to compare these two indicators (one is considered in complexity points, and the second - in man-hours or money spent).

The second chart shows not very bright prospects. We spend more money than we expected. Perhaps due to the fact that we have attracted additional resources to achieve the expected productivity. When all three factors are shown in one diagram, we immediately see the problems, and iteration 4 in this example is the moment when we should talk with the client before it is too late.

In order to track the volume of work and budget in this way, we need:

In the previous example, we had:

These are our general indicators. The consumption of 120 hours for 6 complexity points means that we spent 2.5% of the budget on 2% of the work.

We need to return once again to the moment when we changed the fixed volume of obligations to the fixed budget. The 300 difficulty points from the previous examples will help us change the content of the original list of user stories. This is one of the most important points that we want to come to by applying a flexible methodology to a fixed price contract.

Agile accepts change easily, we just need to streamline change management in a fixed-price contract. This has always been and remains a difficult part of the work, but with a little help, changing the focus from analyzing requirements to restrictions and limits at the early stages of the process, we welcome changes at any stage of the project.

The difficulty is in convincing the client that the stories can be replaced, since they must be comparable in terms of the amount of effort needed to make them happen. Therefore, if for any reason the client has a new delightful idea that we need to deal with a new set of stories (for example, rated at 20 points of difficulty), then it depends only on the client that we will have to remove the story by 20 points from the end of the list tasks to make room for a new one.

Or maybe the client wants to add another iteration (remember the performance of 20 points per iteration?). Calculating the price of these new stories is very simple:

money = 1 iteration * 80 man-hours * 4 people * $ 100 = $ 24,000

And the most difficult part in this type of contract is when we find out during the work on the project that some stories will take longer than we expected, because they were evaluated “by eye,” and now we know a lot more about them than at the beginning. But even such a situation does not always lead to big problems, because at the same time some stories will take less time than planned. Therefore, I repeat again, tracking during the performance of work under the contract will provide you with very valuable information. Talking about problems early will help in the negotiations, because we will discuss actions that need to be taken to avoid such problems, rather than talking about rescue operations after a grand catastrophe.

To use all these techniques in fixed price contracts, one thing is needed - trust . But, as we know, it is impossible to gain trust simply by describing what wonderful work our team will do for the customer.

Agile principles provide a great way to solve this problem. With each iteration, we create some value for the client. But the most important thing is that we first focus on the most valuable features. Therefore, the best way to gain customer confidence is to break the contract into several parts.

Start small, with a pilot part in 2-3 iterations (which will also be with a fixed price, but shorter). The resulting software should live up to the customer’s value expectations. In fact, these should be some of the working parts of key functions. A working product will prove that you can do the rest. It will also give you the opportunity to confirm your initial assumptions about performance and discuss the next part.

The time spent on the pilot should also be small compared to the amount of work that remains to be done. In this case, if the client is dissatisfied with the results, he will be able to refuse your services before it is too late, he will not have to renew the contract and ultimately fail the project.

Fixed price contracts are often perceived as very, very bad, and many agile adherents say they should be avoided. But in most cases, you cannot avoid them, so you need to look for ways to make them work for our goal - to create high-quality software.

In fact, some aspects of fixed factors are even better for agile teams, because we are used to working in time blocks, and a fixed date in the contract (as well as a fixed price) are these time blocks and boundaries. The only thing that really bothers us is the volume of obligations, and in this article we tried to collect ideas on how to cope with this restriction.

The idea of this article was not to say that agile is a panacea for all the problems of fixed-price contracts, but to show other ways of working in this area using a flexible methodology.

Marcin Niebudek is a businessman and co-owner of Agilers and the creator of tinyPM , a small tool for managing agile projects. Marsin is insanely idealistic about software development and firmly believes in this path. He likes to experiment with all areas of Agile and Lean Development technology. He also likes to write software, read about it, think about it and blog about it. He is the author of the Battle for Agility blog, which describes the agile movement in the Polish IT industry. Marsin is a Java developer with over 8 years of experience in creating enterprise systems using all kinds of technologies from the Java EE arsenal.

How can a company execute such a contract using a flexible methodology to achieve better results with less risk? In this article we will try to answer these questions.

So let's start with the contract itself.

Fixed price, time and volume of obligations

Such contracts immediately fix three magic factors - money, time and volume of obligations. Is price and timing an issue for agile teams? Well, shouldn't be. In fact, timeboxing is a common practice. Limiting the budget only helps timeboxing work better.

The real problem with fixed price contracts is the volume of obligations, because it is usually spelled out what exactly needs to be done, instead of exactly how much we should work.

Why are customers so obsessed with a fixed amount of commitment? We understand that they want to know how much they will have to pay (and who does not want?) And when they will get the result. The only thing they don’t know is what exactly they want to receive (even if they say they know).

The roots of the problem with a fixed amount of obligations are as follows:

- Lack of trust between customer and contractor

- Lack of understanding of the software development process

- Misunderstanding of what “scope of obligations” means.

Each fixed price contract has an accompanying document, “Terms of Reference” or something like that. This document is designed to reduce the risks of missing out on something important and to create a common understanding of what needs to be done, which creates an illusion of predictability.

The main erroneous assumptions when fixing the volume of obligations :

- The more details we include in determining the scope of obligations, the better we will understand each other.

- A clearly defined commitment will prevent change

- A fixed amount of commitment is needed to better calculate the price and time.

From a fixed amount of commitment to a fixed budget

Now that we understand that the main conflict between the use of flexible thinking and a fixed price contract lies in a fixed amount of obligations, we can focus on converting a fixed amount of obligations into a fixed budget.

This means that instead of providing a detailed specification of requirements, we need to focus on tracking as many requirements as possible in the form of user stories. We need to build an initial list of tasks for the product, which we will try to evaluate using the technique of difficulty points (story points) and team-wide assessment techniques, such as poker planning (Planning poker).

First, we must understand that a higher level of software granularity means completely different things for both parties to the contract. Software companies usually focus on technical details, while the other side is more focused on the financial side of the issue. Requirement specifications are usually created by software companies and are precautionary. This is where the three key players come into play.

User storiesas a way of expressing requirements, it is clear to both customers and performers. Understanding creates trust and a sense of shared vision for the project. User stories are easy to write and erase, especially if you write them on cards. They are also functional oriented, therefore they provide a clear vision of the real volume of work on the project, and we can compare them with each other in terms of time and effort.

Difficulty points(story points) as a way of evaluating stories is difficult to explain to the client at first, as this is not an ordinary way of expressing efforts. But on the other hand, they reduce the risk of underestimating the volume of obligations. How does this happen? The complexity scores are relative in nature, the focus here is either on the total volume, or on a group of stories, while the traditional assessment (usually done in man-hours) tries to analyze each function individually.

Readiness criterion(definition of done) is another method of building trust and a common understanding of processes and planning in a project. Usually, when a client first encounters user stories, even if he likes the way they are written, it is not obvious to him what the story implementation is. Teams that discuss readiness criteria with a client have a better understanding of what they expect from them. They also provide a more accurate estimate. In addition, on the client side, the availability criterion creates the conditions for a higher level of acceptance of user history.

For example, the readiness criterion for stories in a fresh web application might include the following items:

- Tested under IE 7/8, Firefox 3.x and Chrome

- The corresponding sections in the “User Guide” have been created.

Later, the team can create other, deeper internal elements of the readiness criterion, but at the stage of preparing the contract, these general instructions give the client and the team an understanding of what we want to create within the scope of the project.

We hope that taking into account our readiness criterion, we will come to a certain value that will decompose the project budget into complexity points . And this value, and not the user stories that stand behind it, is the first thing that should be recorded in the contract. And that already opens the door to change.

Although we have a fixed amount of commitment, we still want to accept changes flexibly. We have tools (stories and difficulty scores) that you can use to compare requirements. This allows us to exchange requirements, remaining within a fixed volume of obligations. And if we can stay within this framework, then we can and fit into a fixed time frame and price.

Initial assessment

The most difficult part of preparing a fixed price contract is determining the price and schedule, which will be fixed on the basis of a well-defined scope of obligations. Let's see what a team can bring to such a contract with a flexible initial project evaluation.

Firstly, training . Meet with the client and tell how you will work. We should tell him what user stories are, how we are going to evaluate them, and what is the readiness criterion. Often, this must be done before preparing a proposal for a client request for proposal (RFP).

The next step is to collect user stories.. It can be organized as several quick sessions in 1-2 days. This time is enough to find most of the stories that will form the vision of the product without getting deep into the jungle of functionality. From this point of view, it is very important to discuss with the client the readiness criterion for stories, iterations and releases.

We should know:

- The environment in which you want to test stories (the number of browsers or mobile platforms, or operating systems)

- Required Documentation

- Where do you need to unfold completed stories so that the client can look at them

- What should the client do (for example, take part in a demo session)

- How often to meet and who are the participants

These and, probably, many more factors will influence the assessment and give a common understanding of expectations and quality on both sides. They will also help to make the assessment less optimistic, what is it if the team discusses only the technical aspects of implementing user stories.

Having discussed with the customer a set of stories and the readiness criterion, we can begin the assessment. This is a well-known part of the process. Here, the most important action is to involve as many future team members as possible so that the assessment is carried out collectively.

Techniques such as planning poker reduce the risk of underestimating a project due to the opinion of an individual team member, especially if this team member is also the most experienced, which is exactly what happens when one person is involved in the evaluation. It is also important that the stories are evaluated by people who will actually implement the system.

A scale similar to the Fibonacci series (1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40, 100) is very convenient for evaluating stories in complexity points. A relative assessment begins with a selection of the simplest or smallest stories. They get 1-2 points of difficulty - this is the basic level for further evaluation.

In fact, during the initial assessment it is often difficult to evaluate the stories using the lowest values, such as 1 and 2. The fact is that the higher the score, the less we know about the story. Therefore, scoring is easier at this initial level, because it’s much easier to say that story A is 2 times more complicated than story B than to say that story A will take 25 person-hours (remember the readiness criteria?), And story B will take 54 hours.

This works great, even if we take 3 or 5-point stories as a basic level, in which case it will be easier for us to break them into small stories already at the development stage. Beware of stories with 20, 40 or 100 points. This method of evaluation assumes that we do not know anything about what will be implemented, so we need to immediately discuss everything in more detail with the customer, and not happily enter them into the contract.

The result of the assessment is the total number of difficulty points that describe the initial amount of work to create a product. This number should be recorded as the volume of obligations under the contract, and not individual user stories.

Price and time fixing

The total number of difficulty points calculated on the basis of a set of stories does not directly give us price and time. How to get them? We need magic numbers.

Do not be surprised, because in contracts with a fixed price there are always magic numbers. All estimated values have always been such numbers. Now we are changing the way we evaluate, but in the end we still need to predict the future based on past experience. So what should we know? Predicted team performance.

Suppose we rated our stories with a total of 300 reference points. We need to determine team performance based on the following:

- Team Performance on Past Projects

- The number of actions performed at each iteration (see Readiness Criterion)

- Ease of communication with the client (of course, the ideal and difficult to reach option is when the client is in place as part of the team, but usually it is not. Different customers have different amounts of time that they are willing to spend on communicating with the team) - the less time there is the customer is on us, the lower our productivity

- Just the sensations that the volume of work on the project arouses in us (yes, we wish it out as valid)

Suppose our team consists of 5 people - 3 programmers, 1 tester and 1 team leader - who will communicate with customers and interested parties, just like with other people outside the team (for example, Scrum Master in the Scrum methodology).

Let's say that our team will try to achieve a speed of 20 reference points in a 2-week iteration. This is our main magic number in the contract. Many factors can affect productivity during the whole time of working on a project, however, if the team we are working with is not new, and the project itself is not something completely unknown, then these numbers can be taken from past experience.

Now we may encounter one of two restrictions imposed on us by the client in the contract:

- The client wants to receive the product as soon as we can make it (and, preferably, even faster)

- The client wants us to do the maximum by date X (which is our deadline)

Scenario 1

In the first scenario, we can determine the estimated completion time using the following formula:

time = (<complexity points> / <performance>) * <iteration length>

In our scenario, it will be:

time = (300 points / 20 points) * 2 weeks = 30 weeks (or 15 iterations)

If the estimated time is unacceptable, then the only thing we can change is the performance of the team. Be that as it may, the dependence is not linear, and if we double the team size, the performance will not double.

Scenario 2

We know that the project will be completed in 20 weeks, and this is only 10 of our iterations, so we can only perform 20 points from our scope of work. Now it depends on the client what can be removed from the scope of work without losing the ability to do something that has the necessary value.

Here we can also (to some extent) resize the necessary team to increase productivity.

Knowing the required size of the team and end date, we are finally able to calculate the basic price of the contract - the cost of work:

money = <number of hours per iteration> * <number of iterations> * <people> * <the price of an hour of work>

The In our example, we get:

money = 80 hours * 15 iterations * 4 people * $ 100 = $ 480,000

Now we have the values of a fixed price contract:

- price - $ 480,000

- time - 15 iterations (30 weeks)

- volume - 300 reference points

These simple calculations, of course, are only part of the value that will ultimately appear in the contract, but it is also the most difficult part to determine. We wanted to show that the way we work on flexible projects can also be transferred to the contract negotiation process.

There is one more question. The client asks: “Why is it so expensive?” This is where the negotiations actually begin, and the only factor that the manufacturing company can change is the cost of a man-hour. These are the $ 100 we are negotiating about. Not the length of the iterations, not even the number of iterations. Our team has no super powers, and we will not work twice as fast if we just agree on this.

This is the money that we agree to lose. If we say that we can lower the price, it is only because we earn less, and not because we will work faster.

Track your progress and budget.

Now our contract has been signed (it was easy, right?), It’s time to create software in an agreed framework. You have probably already heard that a flexible methodology will not solve your problems, but will make them visible. Therefore, we want to know early how things are going in order to take the necessary actions. After all, there is a possibility that our magic number in the contract (our performance) was erroneous.

Burndown charts are a very common way to track progress in many agile projects.

Рис. 1 — Запланированный прогресс и реальный прогресс.They are great for visualizing planned progress and reality. For example, the burndown chart in Figure 1 looks good:

We do not fit into the plan a bit, but this does not mean that we made a big mistake in determining the performance in the process of discussing the contract. Probably many teams would want their graphics to look that way. But the problem is that this graph displays only two of the three factors - the amount of commitment and time. But what about the money?

Рис. 2 — Прогресс выполнения работ и расходования бюджета.The diagram in Fig. 2 shows two scales - the amount of work and the budget. These two factors are expressed here as a percentage of good reason. After all, there is no other way to compare these two indicators (one is considered in complexity points, and the second - in man-hours or money spent).

The second chart shows not very bright prospects. We spend more money than we expected. Perhaps due to the fact that we have attracted additional resources to achieve the expected productivity. When all three factors are shown in one diagram, we immediately see the problems, and iteration 4 in this example is the moment when we should talk with the client before it is too late.

In order to track the volume of work and budget in this way, we need:

- Track completed difficulty points at each iteration

- Track the time actually spent at each iteration (in man-hours)

- Recalculate points as a percentage of total work and draw a scale based on a percentage of total

- Recalculate the budget fixed in the contract (or part of it) into the total number of man-hours — these are our 100% of the budget — and draw a budget spending scale based on a percentage of the total budget

In the previous example, we had:

- Scope of work - 300 points of difficulty

- 30 week budget * 4 people * 40 hours per week = 4,800 man hours

These are our general indicators. The consumption of 120 hours for 6 complexity points means that we spent 2.5% of the budget on 2% of the work.

Acceptance of changes

We need to return once again to the moment when we changed the fixed volume of obligations to the fixed budget. The 300 difficulty points from the previous examples will help us change the content of the original list of user stories. This is one of the most important points that we want to come to by applying a flexible methodology to a fixed price contract.

Agile accepts change easily, we just need to streamline change management in a fixed-price contract. This has always been and remains a difficult part of the work, but with a little help, changing the focus from analyzing requirements to restrictions and limits at the early stages of the process, we welcome changes at any stage of the project.

The difficulty is in convincing the client that the stories can be replaced, since they must be comparable in terms of the amount of effort needed to make them happen. Therefore, if for any reason the client has a new delightful idea that we need to deal with a new set of stories (for example, rated at 20 points of difficulty), then it depends only on the client that we will have to remove the story by 20 points from the end of the list tasks to make room for a new one.

Or maybe the client wants to add another iteration (remember the performance of 20 points per iteration?). Calculating the price of these new stories is very simple:

money = 1 iteration * 80 man-hours * 4 people * $ 100 = $ 24,000

And the most difficult part in this type of contract is when we find out during the work on the project that some stories will take longer than we expected, because they were evaluated “by eye,” and now we know a lot more about them than at the beginning. But even such a situation does not always lead to big problems, because at the same time some stories will take less time than planned. Therefore, I repeat again, tracking during the performance of work under the contract will provide you with very valuable information. Talking about problems early will help in the negotiations, because we will discuss actions that need to be taken to avoid such problems, rather than talking about rescue operations after a grand catastrophe.

Building trust

To use all these techniques in fixed price contracts, one thing is needed - trust . But, as we know, it is impossible to gain trust simply by describing what wonderful work our team will do for the customer.

Agile principles provide a great way to solve this problem. With each iteration, we create some value for the client. But the most important thing is that we first focus on the most valuable features. Therefore, the best way to gain customer confidence is to break the contract into several parts.

Start small, with a pilot part in 2-3 iterations (which will also be with a fixed price, but shorter). The resulting software should live up to the customer’s value expectations. In fact, these should be some of the working parts of key functions. A working product will prove that you can do the rest. It will also give you the opportunity to confirm your initial assumptions about performance and discuss the next part.

The time spent on the pilot should also be small compared to the amount of work that remains to be done. In this case, if the client is dissatisfied with the results, he will be able to refuse your services before it is too late, he will not have to renew the contract and ultimately fail the project.

Summary

Fixed price contracts are often perceived as very, very bad, and many agile adherents say they should be avoided. But in most cases, you cannot avoid them, so you need to look for ways to make them work for our goal - to create high-quality software.

In fact, some aspects of fixed factors are even better for agile teams, because we are used to working in time blocks, and a fixed date in the contract (as well as a fixed price) are these time blocks and boundaries. The only thing that really bothers us is the volume of obligations, and in this article we tried to collect ideas on how to cope with this restriction.

The idea of this article was not to say that agile is a panacea for all the problems of fixed-price contracts, but to show other ways of working in this area using a flexible methodology.

about the author

Marcin Niebudek is a businessman and co-owner of Agilers and the creator of tinyPM , a small tool for managing agile projects. Marsin is insanely idealistic about software development and firmly believes in this path. He likes to experiment with all areas of Agile and Lean Development technology. He also likes to write software, read about it, think about it and blog about it. He is the author of the Battle for Agility blog, which describes the agile movement in the Polish IT industry. Marsin is a Java developer with over 8 years of experience in creating enterprise systems using all kinds of technologies from the Java EE arsenal.