How the sugar industry paid for Harvard's research on fat damage

- Transfer

Dr. Cristin Kearns discovered papers stating that the sugar industry sponsored a study diminishing the role of sugar in the development of heart disease.

In the 1960s, when there was a heated debate about nutrition, Harvard nutritionists published two studies in the largest medical journal degrading the role of sugar in the occurrence of coronary heart disease. But recently discovered documents reveal new details: the sugar industry trade group launched this research, paid for it, checked drafts, and set a goal to protect sugar’s reputation before public opinion.

This discovery is published on Mondayin the journal JAMA Internal Medicine, was made by Dr. Christine Kearns of the University of California, San Francisco. She retrained from dentists to researchers, and found traces of the sugar industry, digging in boxes with letters in the basement of the Harvard laboratory.

In her work, she recounts the story of how two famous Harvard nutritionists, Dr. Frederick Star [Fredrick Stare] and Mark Hegsted [Mark Hegsted], now deceased, worked closely with the trading group “Sugar Research Foundation”, attempting to influence public opinion related to the role of sugar in the occurrence of the disease.

The trade group urged Hegstead, a professor of nutrition at Harvard Public Medical School, to write a review rejecting the findings of earlier studies linking sucrose and coronary heart disease. The group paid the equivalent of today's $ 48,000 to Hegsted and his colleague, Dr. Robert McGandy, and the researchers did not advertise the source of funding.

Hegsted and Star did not leave a stone unturned in studies that revealed sugar, and concluded that in order to prevent disease in the diet, it is only necessary to change the consumption of fats and cholesterol. These reviews were published in 1967 in the New England Journal of Medicine, whose rules at the time did not require scientists to disclose possible conflicts of interest.

At that time, researchers argued which product, sugar or fats, was responsible for the deaths of many Americans, especially men, from coronary heart disease - the accumulation of plaques in the heart arteries. Kearns says that the work the trading group subsequently quoted in booklets meant for regulators helped increase the market share of sugar, convincing Americans of the benefits of a low-fat diet.

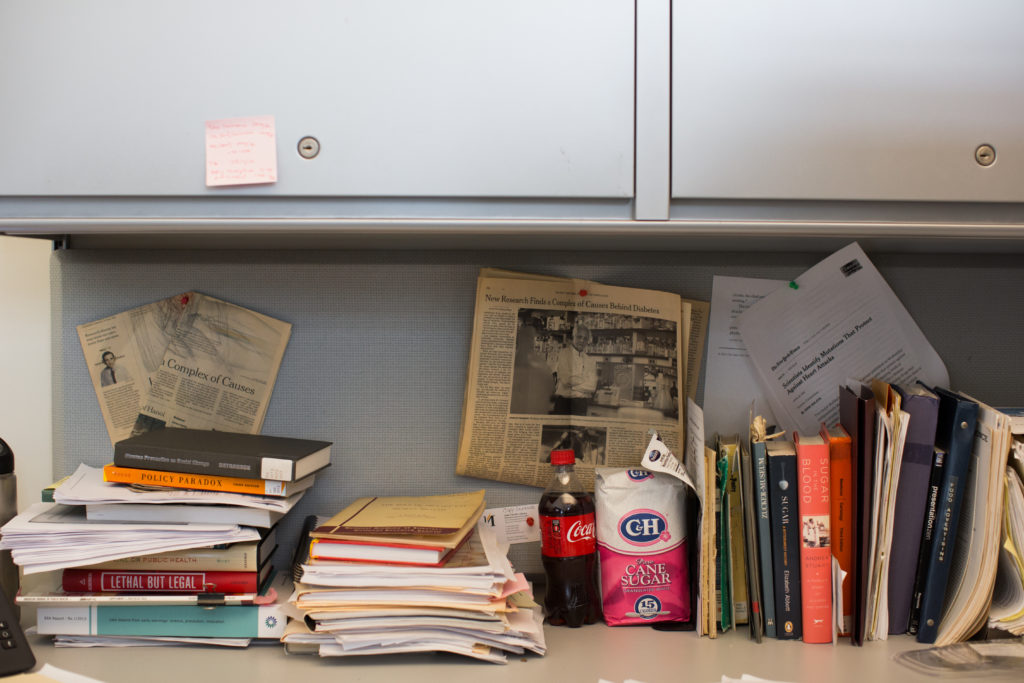

Kearns calls these documents stored in her office "sugar papers."

Almost 50 years later, some nutritionists consider sugar to be one of the risk factors for heart disease, although there is no agreement among their ranks. Two large studies published in an influential journal “helped move the subject of controversy from sugar to fat,” says Stanton Glantz, co-author Kearns and her manager at UCSF. “It has delayed the development of a scientific consensus about sugar and heart disease for decades.”

Marion Nestle, a nutritionist at New York University who did not participate in the work, said that she was not yet convinced by the arguments of those who believe that “sugar is poison”. The total amount of calories consumed by a person may be more. But she called the find "smoking gun" - a rare example of irrefutable evidence of the machinations of the food industry in science.

“Science should not act that way,” she wrote in a comment . “Is it true that food companies specifically try to manipulate research in their favor? Yes, this is true - and this process continues, ”Nestlé added, noting that Coca-Cola and candy makers had recently tried to influence nutritional research.

In a statement, the sugar trading group claims that the very study is being criticized unfairly. “We recognize that the Sugar Research Foundation should have acted with greater transparency in its work with research,” the group, Now known as the Sugar Association, writes. But "it is very difficult for us to comment on events that took place 60 years ago, and documents that we have not seen at all."

“Sugar does not play a crucial role in causing heart disease,” the group said. “We are disappointed that JAMA-level magazine uses high-profile articles to refute high-quality scientific research.”

Kearns, a fragile and quiet woman, often blushing when talking, is not suitable for the role of a crusader in the fight against the sugar industry. She studied as a dentist, and told how shocked she was when in 2007 at a dentist conference a speaker on diabetes argued that there was no evidence linking sugar with chronic diseases. She quit and devoted herself to the disclosure of documents showing the influence of the sugar industry on public opinion and science.

Now she has managed to collect 2000 pages of internal documentation. She keeps them in two fireproof cabinets at her workplace at UCSF, along with photos of decaying teeth and boxes of Cocoa Pebbles and Cinnamon Toast Crunch sweets.

Her previous work demonstrated how the sugar industry influenced the government's dental research program, instead of exploring the benefits of reducing sugar intake, looking for medicines for tooth decay.

For her new research, Kearns flew to Boston in 2011 and spent several days in the Kountway Library at Harvard Medical School, rummaging through boxes of letters left by Hegsted.

Hegsted, according to Nestlé, was a “hero of nutritionists”. He helped create the draft US Dietary Objectives report for the Senate of 1977, which paved the way for the first dietary rules of the country. He oversaw the nutrition department at the Ministry of Agriculture.

Looking through his letters, Kearns was "shocked" by the level of his cooperation with the sugar industry.

She discovered that in the 1950s, the Sugar Research Foundation determined a strategy to increase its sugar market share by transplanting Americans on a low-fat diet based on a study blaming fat and cholesterol for high blood pressure and heart problems. All this was described in a speech from 1954, with which the president of the trade group spoke.

John Hickson, vice president of the Foundation and director of research, carefully examined the course of nutrition research. In an internal memo from 1964, found by Kearns, he suggested the group “launch a large campaign” in order to “resist the negative attitude towards sugar”, partly by financing their own research, designed to “refute our slanderers”.

Hickson hired Stair, chairman of the nutrition department at Harvard Medical School, to join a panel of experts from the foundation. In July 1965, immediately after the appearance of the articles linking sucrose - ordinary table sugar - to coronary heart disease, which appeared in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine, he turned to Hegsted for help. Hickson agreed to pay for the services of Hegsted and McGandy, which was led by Star, $ 6500 (taking into account inflation today is $ 48000). The services included writing "articles with a review of several articles describing a certain threat to metabolism found in sucrose."

Hegsted asked Hickson to provide articles. Hickson sent at least five articles threatening the sugar industry - which suggests that his intentions included their criticism. So, at least, Kearns and colleagues argue.

Kearns stores sugar-containing products in his office.

Objectives of the review Hickson said: “We are particularly interested in the part about nutrition, which states that carbohydrates in the form of sucrose make an excessive contribution to metabolism, and lead to deviations under the name of fat metabolism. I will be disappointed if this aspect sinks into review and general interpretation. ”

Kearns argues that Hegsted replied: "We are well aware of your interests in the field of carbohydrates and we will review with all possible care."

Kearns discovered that scientists communicated with the sponsor not only before starting work, but also in the process. In April 1966, Hegsted wrote to a trade group to report a review delay in connection with a new study, in which scientists from Iowa found new evidence linking sugar with coronary disease. “Every time the Iowa group publishes a work, we have to redo the rebuttal,” he wrote.

From the letters it follows that Hickson checked drafts of works, although it is not known whether any comments or corrections were received from him.

“Will I receive another copy of the draft soon?”, Higson asked Hegsted, according to Kearns. “I think I can make it for you in a couple of weeks,” replied Hegsted.

Hickson received the final draft of the work a few days before Hegsted was about to publish it. The sponsor was pleased: “I hasten to assure that we had in mind just such a job, and we look forward to her appearance in print,” wrote Hickson. When the work was published the following year, the authors mentioned that it received funding from other sponsors, but did not give out a word about the Sugar Research Foundation.

The Hegsted reviews covered a wide range of studies. He refuted the work in which sugar was called the cause of coronary disease. He found merits only in those works that blamed fats and cholesterol for everything.

Glanz, co-author of Kearns, said that the main problem with the reviews was that they were unfair: when sugar was accused, Hegsted and his colleagues swept aside whole classes of epidemiological data. But they did not subject such criticism to articles that blamed fats.

He says that the cooperation level of Harvard researchers is clear: “The industry says, 'These are works that we don’t like. Get familiar with them, ”says Glanz. - And they figured it out. This is what struck me the most. ”

Glanz says that the sugar industry copied tobacco in its actions, about which internal documents he wrote a lot. From the letters you can see how difficult moves sugar industry businessmen used to change public opinion, he says. They carefully tracked the research and carefully chose which scientists to turn to. “They treated them carefully, and as a result they got what they wanted,” says Glantz.

Glanz, Kearns and their co-author, Laura Schmidt, admit that their research was limited by the inability to interview already deceased participants in the events.

Dr. Walter Willett, who knew Hegsted and currently the head of nutrition at Harvard Medical School, protects him as a scientist with principles. “He was a very purposeful person who trusted only the data, and in his life, he used to oppose the interests of the industry,” Willet wrote in a letter. For example, Hegsted lost his job in the USDA due to getting up on the road in the meat industry. "I very much doubt that he has changed his principles, or made conclusions based on obtaining funding from the industry."

Willet says it has become clearer today that refined carbohydrates and sugary drinks "are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases," and that "the type of fat consumed is also very important." But he says that, during Hegstead’s work, the evidence that claimed fats were risk factors for coronary diseases was “much stronger” than evidence of harm to sugar. He argues that he would agree with “most interpretations” made by researchers.

“However, since he [Hegsted] received funding from the sugar industry and was constantly in touch with them,” Willet admits, “he found himself in a position where his conclusions could be doubted. It is also possible that such a relationship could lead to a slight bias, albeit subconscious. "

Willet called the historical report "a useful warning that obtaining funding from the industry is a research problem, as it may lead to the publication of biased works." He says that "in the case of reviews, this is doubly problematic, since they include evaluative judgments of data interpretation."

But Willet, whose professorship is named after Frederick Stair, says that Star and his colleagues did not break any rules. Conflict of interest standards have changed a lot since the 1960s. Since 1984, the New England Journal of Medicine has required authors to report inconsistencies. The journal also requires authors to support “research support” reviews from relevant companies.

NEJM spokeswoman Jennifer Zeis said that the magazine now requires authors to publish information about all financial inconsistencies that have arisen during the 36 months prior to publication, and also conducts a thorough peer review that helps prevent potential conflicts of interest.

Glanz says it would be worth it for a magazine to make an editorial column on what “really happened” with that review. “The origin of this work is highly misleading,” he says. Zays says that the magazine has no such plans. And Keynes continues his campaign to open more internal documents of the sugar industry.

In a recent foodcourse interview at UCSF, she abandoned chocolate chip cookies in favor of a chicken sandwich and fruit salad. She says that she partially acts on the basis of her experience as a dentist - she has seen patients with decayed teeth, including a person who needed a dental prosthesis as early as 30 years.

The government supports such researchers as Keynes, speaking about the dangers of sugar - new recommendations on nutrition suggest that people receiving less than 10% of calories from sugar in foods.