Security Week 29: Zoom, Security, and Drama Vulnerability

Last week, researcher Jonathan Leytsach published a highly emotional post about Zoom web conferencing client vulnerabilities for macOS. In this case, it is not entirely clear whether the vulnerability was an unintended bug or a pre-planned feature. Let's try to figure it out, but in short, it turns out like this: if you have the Zoom client installed, the attacker can connect you to his newsgroup without demand, moreover, he can activate the webcam without asking for additional permissions.

Last week, researcher Jonathan Leytsach published a highly emotional post about Zoom web conferencing client vulnerabilities for macOS. In this case, it is not entirely clear whether the vulnerability was an unintended bug or a pre-planned feature. Let's try to figure it out, but in short, it turns out like this: if you have the Zoom client installed, the attacker can connect you to his newsgroup without demand, moreover, he can activate the webcam without asking for additional permissions.The moment when, instead of searching for a patched version, someone decides to simply remove the client from the system. But in this case it will not help: a web server is installed with the client, which works even after uninstalling - it is even able to “return” the client software to its place. Thus, even those who once used Zoom services, but then stopped, were in danger. Apple came to their aid, without much fanfare, which removed the web server with an update for the OS. This story is a real infosec drama, in which users can only watch how various software appears and disappears on their computers.

The study of Zoom client’s working methods began with the study of the local web server: the service website tries to access it when opening a link to connect to a newsgroup. A relatively elegant method was used to query the status of a local server - by transmitting an image of a certain format.

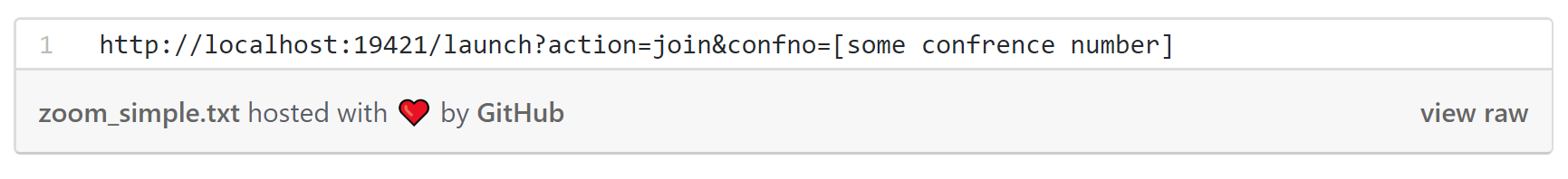

This is done to circumvent the limitations of the browser following the rules of Cross-Origin Resource Sharing . You can also send a conference connection request to the Zoom web server. This query looks something like this:

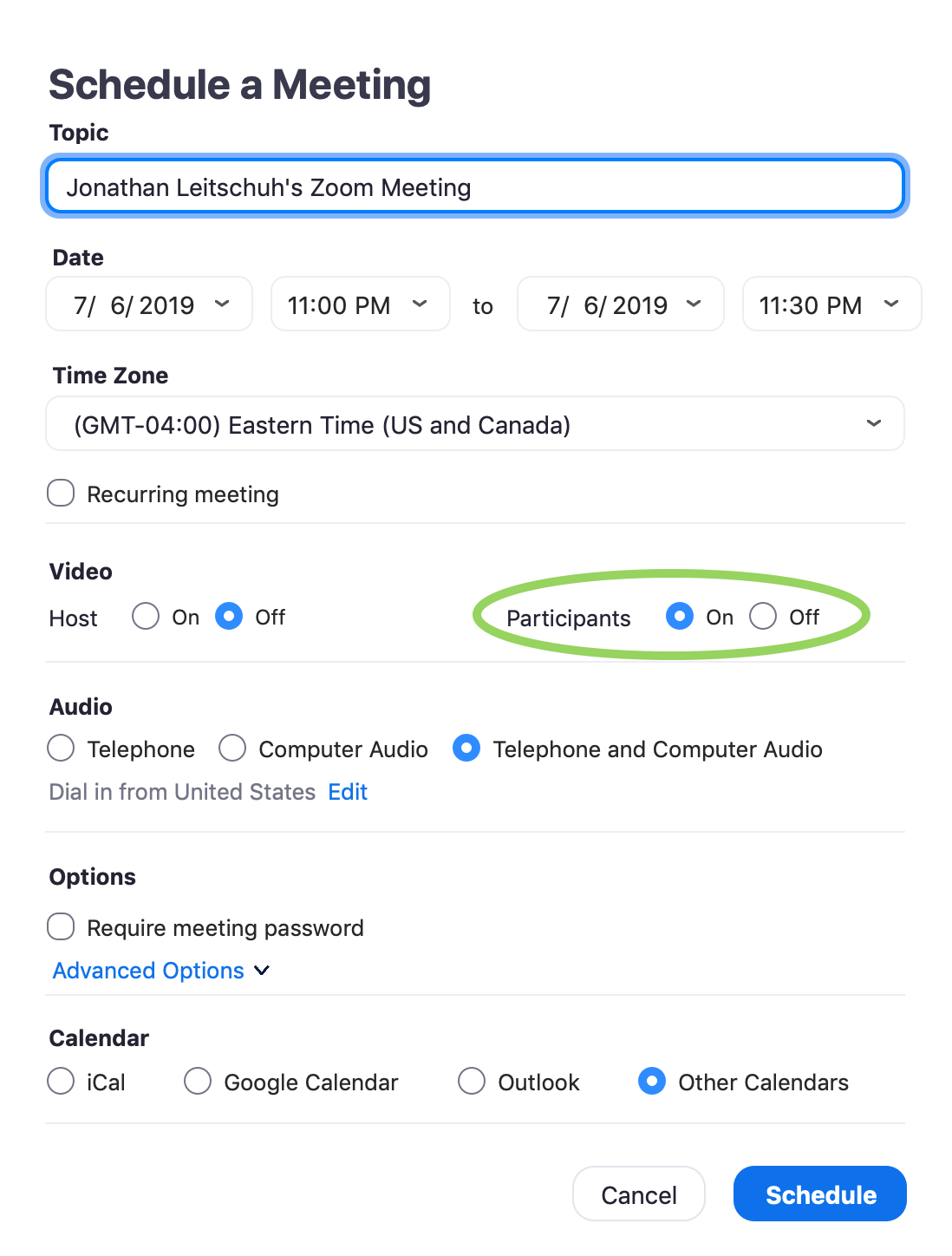

You can create a conference, place a similar request on a web page, send a link to the victim, and the client installed on the computer will automatically connect the user. Further it is worth looking at the parameters of the web conference itself:

You have the option of forcing the user's webcam to turn on. That is, you can lure an unsuspecting person into a conference call and immediately receive an image from the camera (but the victim will need to manually turn on the sound from the microphone). In the Zoom client, the automatic inclusion of the camera can be blocked, but with the default settings, the camera turns on immediately. By the way, if you send requests to connect to the conference continuously, the Zoom application will constantly switch focus to itself, preventing the user from somehow canceling this action. This is a classic Denial Of Service attack.

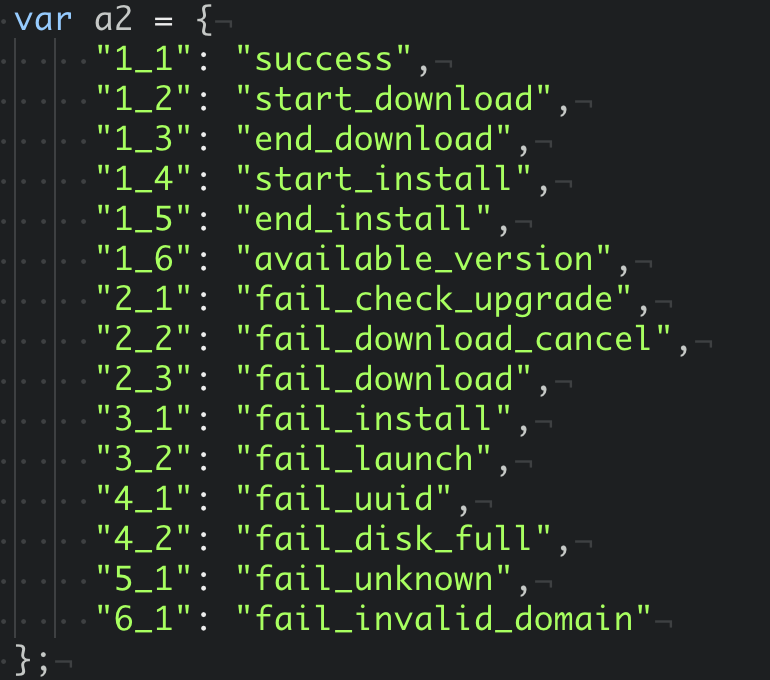

Finally, the researcher confirmed the ability to force upgrade or reinstall the Zoom client if a web server is running on the computer. The vendor’s reaction was initially far from ideal. The developers of Zoom proposed several options for “patches” in the logic of the web server to exclude the possibility of connecting users without demand. All of them easily got around or complicated the life of a potential attacker a little. The final solution was to add another parameter passed to the local server. As the researcher found out, it did not solve the problem either. The only thing that was precisely repaired was the vulnerability that allowed a DoS attack. And on Jonathan’s proposal to remove the inclusion of a webcam at the request of the conference organizer, the answer was completely given that this is a feature, “it’s more convenient for customers”.

The first time a researcher tried to get in touch with Zoom developers on March 8th. On July 8, the generally accepted three-month deadline for fixing the vulnerability expired, and Jonathan published a post about what he considered an unsolved problem. Only after the publication of the article did Zoom take more radical measures: on July 9, a patch was released that completely removes the web server from computers running macOS.

Dear editors regularly communicate via videoconferencing and can say from personal experience: everyone does it. Not in the sense that everyone installs a local web server with the client and then forget to delete it. All or almost all conferencing services require more privileges on the system than a browser page can provide. Therefore, local applications, browser extensions, and other tools are used, so that the microphone and camera work during the communication process, you can share files and the image of your desktop. Frankly, the “vulnerability” (or rather, a deliberate mistake in the logic) of Zoom is not the worst thing that happened with such services.

In 2017, a problem was discovered.in the browser extension of another conferencing service - Cisco Webex. In that case, the vulnerability allowed arbitrary code to be executed on the system. In 2016, the Trend Micro password manager also found a problem in the local web server, which also opened up the possibility of arbitrary code execution. At the end of last year, we wrote about a hole in the Logitech keyboard and mouse utility: even there we used a local web server, access to which was possible from anywhere.

Conclusion: this is a fairly common practice, although from a security point of view it is clearly not the best - there are too many potential holes with such a web server. Especially if it is created by default for interacting with external resources (for example, a site that initiates a web conference). Especially if it cannot be deleted. The ability to quickly restore the Zoom client after uninstallation was explicitly made either for the convenience of users, or for the convenience of the developer. However, after the publication of the study, this brought additional problems. Okay, active Zoom users got an update and the problem was resolved. And what to do with those who once used the Zoom client, then stopped, but the local web server still works for them? As it turned out, Apple quietly released an update,

We must pay tribute to the developer of the Zoom service: after, so to speak, a negative reaction from the public, they solved the problem and now regularly share updates with users. This is clearly not a success story: here, the developer also politely tried to ignore the real suggestions of the researcher, and the researcher called what he is not quite a “tyrant”. But in the end it all ended well.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this digest may not always coincide with the official position of Kaspersky Lab. Dear editors generally recommend treating any opinions with healthy skepticism.