Who needs GPS? Etak's Forgotten 1985 Navigator Story

- Transfer

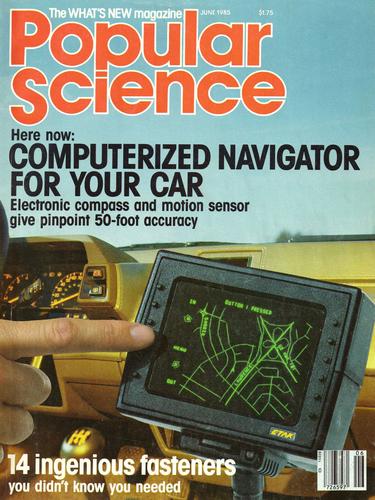

June 1985 Magazine Cover

Thirty years ago, Etak launched a computer-based navigation system for cars. The project was led by engineer Stan Honey, and financed by Nolan Bushnell, co-founder of Atari. The navigator was so ahead of his time that the phrase "ahead of his time" seems like a wild understatement.

For an adequate assessment of this amazing phenomenon, it is necessary to recall that the GPS satellite global positioning system was put into operation only in 1995. And then, at the request of the FBI, its accuracy was limited to 100 meters, so that the enemies could not use it to direct their missiles. This restriction was removed in 2000, when the era of navigation gadgets began.

Etak was a decade and a half ahead of GPS navigation. The inventors had to digitize the cards on their own and figure out how to store them in the car before SSDs, optical disks and wireless Internet appeared. Yes, yes - they stored data on cassettes!

Almost the entire system had to be developed from scratch. And she earned!

By current standards, the commercial success of the system was weak - but it was not a complete dead end. To create a device, inventors had to come up with technologies and collect data that some navigation applications and devices still use. And here is how it was.

It all started on a yacht

The idea was born on the high seas. Bushnel hired Honey to run his Charlie racing yacht in the 1983 Pacific Regatta, a prestigious competition stretching for 2,225 nautical miles in the open ocean, from Los Angeles to Honolulu.

Charlie's yacht finishes.

Once about 4 in the morning, the men were together at night watch. While the rest of the crew were asleep, these two tried to determine their position using a satellite in Earth orbit. He passed over them every 12 hours. By measuring the Doppler effect in radio waves, special equipment could determine the latitude and longitude of the ship. But the passage of the satellite was a rare event and could only give a starting point for the operation of the navigator.

And in the intervals between flights of the satellite twice a day, Hani needed to calculate their position using ancient methods of navigating stars, sextant and numbering, which required tracking the distance and direction of movement in relation to the previous location.

Charlie's team after the finish. The third left in the front row was blushing. Hani is the third left in the back row.

In this race, Hani also had more modern equipment. Bushnel empowered Honey, who worked as an engineer at SRI International, to create one of Charlie's first computer navigation systems. A computer developed in conjunction with Haney’s colleague, Ken Milnes, assisted the process by reading data from sensors on the ship and adjusting course.

But even with such a computer, navigating the sea was difficult. And the two men started talking about this difficulty. “We joked that it would be easier if there weren’t this soft thing under us,” Bushnel recalls.

And during the shift, they began to think about a computer-based navigation system for ground navigation. Honey suggested that a navigator in a car could track the distance traveled and associate the current position with known points on the map - a technology known as finding matches with the map. He would not need satellites - only a good digital map, a compass and several sensors. The result could be displayed.

“Well, I said that let’s do such a thing, and I’ll finance it,” says Bushnel. “That's how it all began.”

Charlie won the regatta, not least thanks to Hani's computer navigation. After 9 sleepless nights, Bushnel fell in his room and slept for 15 hours. Hani, having rested after the voyage, began to drive in his head ideas about a new, previously unprecedented car navigation system. He has already set a new course - only this time, above ground.

Navigator and Entrepreneur

Stan Honey was born in Pasadena, California, in 1955. From an early age, he immersed himself in marine culture. “I grew up on Indian skiffs and my family’s boat, from about six years old,” he recalls. “I was interested in navigation, because my father was a navigator, and my grandfather, too, during the war.”

While studying at Stanford, Honey joined the SRI program, which explored precise navigation and sensor technology for military and government purposes. In parallel, he worked as a navigator on several regattas. By the time of the regatta in 1983, he had already worked on the Drifter, which had won the same regatta, in 1979.

And if Honey was a navigator, then Bushnel was an entrepreneur. He sold Atari to Warner Communications in 1976. He was 40 years old in 1983, he invested in startups and jumped from one idea to another faster than most people could follow. His company Catalyst Technologies was one of the first incubators. Among others, he financed and assisted ByVideo companies (electronic purchases, 1983), personal robots (Androbot, 1983), and interactive toys such as Furby (Axlon, 1985). None of the projects repeated Atari's success - they usually attracted a lot of attention and then burned out. But he had the ability to see big ideas on the verge of possible.

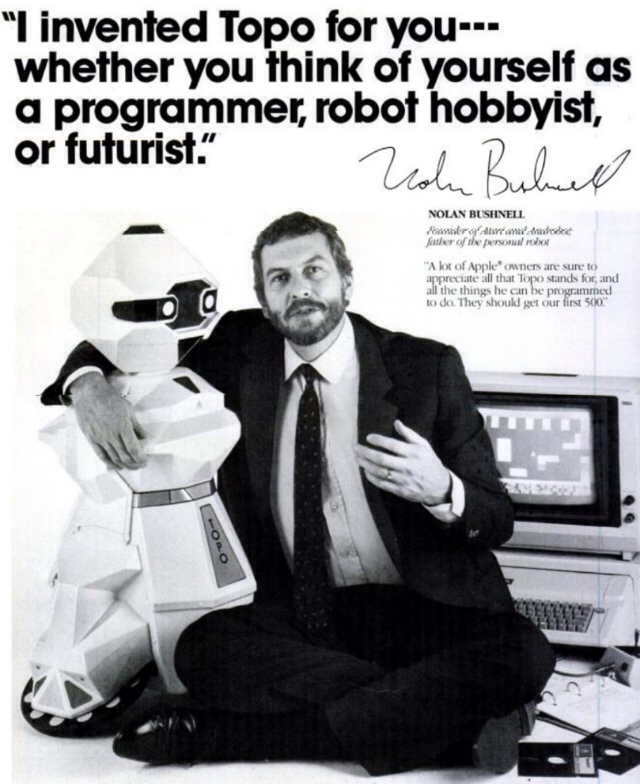

Androbot Robot Advertising

Hani entered the Catalyst office in late 1983. He began to discuss with Bushnel the creation of their company of car navigators. They settled on a typical startup plan for Bushnel startups: Honey will receive the first round of financing, and its offices will be located on Catalyst premises until it can go on a solo trip.

Hani received money and blessings from Bushnell and his colleague, the inventor of the Pong game, Alan Alkorn, and began to build a business. He invited Ken Miles and another SRI colleague, Alan Phillips. For several months, other SRI veterans joined them, including engineer Walter Zavoli.

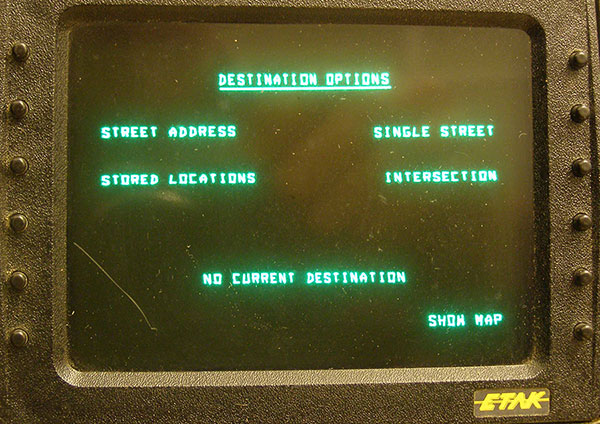

The team’s goal was to build a navigation system that could be put into any stock car. The device would have to tell the driver his location at any time, using a CRT display on the dashboard, show the position of the destination point, and track directions to this point until the driver arrives at it.

The development of iron turned out to be quite simple. In addition to compasses, computers and displays, it was necessary to solve large mathematical problems with data, algorithms and maps. Hani thought about where to get the data for the cards, and how their device would store them, and also access them in a fairly short time.

“I read all the work on this topic,” recalls Hani. It became clear that the team needed a specialist in digital cards with experience in topology in order to effectively store card data. “And I found only two of these guys,” says Honey. I accidentally knew one of them personally, through relatives. ” It was Marvin White, who worked at the US Census Bureau.

Bureau always needed accurate maps for the job. In the 60s, the statistics of the bureau decided that it was necessary to take advantage of the computers that appeared to help make their maps more accurate, while improving route planning for both delivering letters and manually counting residents by going around each house. In the process, they invented an efficient way to store digital maps in the form of points, vectors, and polygons called DIME (Dual Independent Map Encoding). White moved to Washington, joined Hani, and began applying his knowledge to the creation of mapping algorithms.

Soon, the company began to collect a group of digitizers - those who would take data from paper cards and enter them into a computer. Naturally, they started from the San Francisco Bay area. Among their innovations was a system that automatically corrected inaccuracies resulting from scanning aerial photographs. With the tools they developed, they began to digitize cards much faster than would be possible manually.

They needed a good map storage method for use by their navigation computer. The storage medium had to withstand shock and vibration, as well as the heat in a closed car on a summer day. The team settled on a cassette recorder, which was more reliable than a floppy drive.

Testing cassettes that can withstand heat in a car

Each cassette could store 3.5 MB of data - which was a lot for those times. And still, the map of the gulf region spread over six cassettes. Changing cassettes was a problem, especially since conventional audio cassettes began to melt. “Cars have a bad effect on electronics,” recalls Walt Zavoli. “Since customers would have to change cassettes in the direction of travel, we knew that extra cassettes in any case would be on a dashboard under the scorching sun.”

Therefore, they tested different materials for cartridge cases that could withstand the heat. They settled on a polycarbonate shell that could withstand the long-term heat of 105 degrees Celsius.

What about a computer? Ready components were used for it. The computer, which was placed in a case the size of a shoe box, was as powerful as the then IBM-compatible desktop computer - well, that is, not particularly. And he needed to do quite a lot of things at the same time.

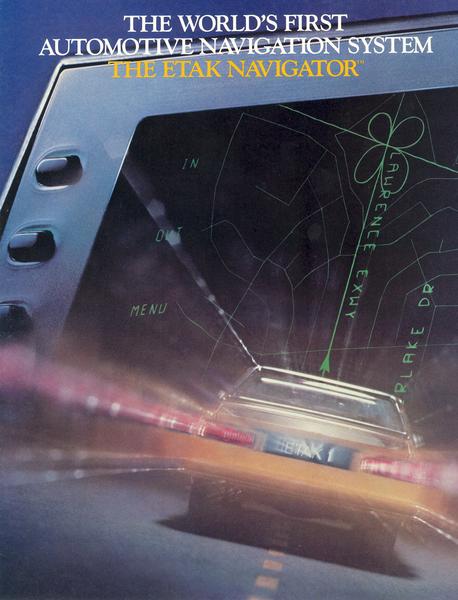

A vector CRT was chosen as the display, which could only draw lines using a single electron gun in the manner of oscilloscopes. A high resolution pixel monitor in 1984 would be extremely expensive. And the vector was simple and clear, as well as bright - which served as an aid on bright days.

On the left - Navigator 700, on the right - 450, and a system for reading data from cards from cartridges.

Without using satellites, the computer needed to read data from sensors. For this, the company developed its own electronic compass, which was mounted on the rear window, and a set of wheel sensors attached to non-driving wheels. They determined the speed, distance and direction of rotation.

Experimenting with the map display, they found that the option with a fixed map and a rotary cursor depicting a car is counterintuitive. Therefore, they settled on the option when the map rotates around the center, denoting a car. Now this is the standard for navigation, and at that time the navigator team created the system.

And this technology reminded Hani about the ancient Polynesian concept of navigation, about which he read, learning on the navigator. They used clues from their surroundings, for example, the positions of the islands around them, combining them with a mental picture in their head, in which they were in the center of an imaginary navigation space. As a result, Hani decided to name the company Etak, which in Polynesian means moving navigation points.

Being ready, the Etak system worked so cool that anyone who used it felt like it was being tricked somewhere. “It was hard for people to believe that it works,” Haney recalls. "It's funny, but it was hard to sell, because no one expected that such a system could even exist."

Etak employee Chuck Hawley installs Navigator on Walt Zawoli's car, Datsun

Today's smartphones can build your route based on GPS sensors that communicate with a network of satellites and maps downloaded wirelessly over the Internet. Hani’s invention needed neither satellites, nor an Internet compass, several sensors, map data, and smart algorithms. And everything worked perfectly. Some modern programs still use the map matching technique to improve the accuracy of the vehicle’s position on the map.

Etak System Brochure

“We essentially took advantage of the fact that drivers usually drive on roads,” says Hani. Algorithms compared the distance traveled with known forms of roads in the database, and placed the car cursor at the desired position on a digital map. When working, the Navigator constantly eliminated the accumulating errors by comparing the distance traveled with the forms of roads on the map.

This meant that driving along a very long, straight stretch of road could confuse Etak - there were no turns and distinctive features there. In this case, the driver could manually change the cursor position on the map using the display adjustment knobs.

Etak engineers decided that allowing the driver to work with the map while driving would be too dangerous, so they forbade entering the destination point or changing the position of the car manually while driving. And this is decades before the whole world began to realize the dangers of distraction from the road when driving a car.

Etak Interface:

Worked idea

System development continued throughout 1984. After testing, it was reduced to two options - 700, which came with a 7 "screen, and 450 - with a 4.5" screen. They called the product Etak Navigator, and began to present it to the press at the end of 1984.

The 1984th for the general investor, Nolan Bushnel, turned out to be difficult. Due to poor management and a fall in the video game market, his promising business Pizza Time Theater went bankrupt, leading to the sale of the unit, Sente Technologies. Bushnel had high hopes for this firm as a source of innovation in the world of video games after he left Atari. However, Pizza Time withstood the vicissitudes, and teamed up with a competitor - now it is known to us as Chuck E. Cheese. Another Bushnel company, Androbot, which promised smart home robots in the 1980s, also failed miserably, earning press reviews in the tone “well, we told you so.”

Stan Honey demonstrates his brainchild in 1986

Etak was a pleasant exception to Bushnell's startups, and without his vision of good ideas, the company might not have appeared. And as usual, Bushnel foresaw what heights the technology could achieve in the future. “Let's say you're in a car and want to eat,” he said in an interview in 1984. - Do you have such a box on the dashboard. You enter “Japanese food”, “cheap” and “good sushi”. And the box takes you where you need to. " The author of the article then snapped: “And where Etak will lead Nolan Bushnell is another question.” But what Bushnel enthusiastically talked about (and Etak planned to add business information to their data) is now implemented in applications like Yelp.

Unlike other Bushnell startups that happened after Atari, which looked fantastic, generated enthusiasm and then failed, Etak expected success and prosperity. Hani recruited very experienced and intelligent people, Bushnell provided them with money, and then let them work independently. “It was a show from Stan Honey,” Bushnel says today. “I was only one of the actors.”

Walter Zavoli recalls Hani with a kind word, as a confident, clear, but not tyrannical manager, comparing him to the navigator he worked on the yacht. “For the most part, Stan sailed the seas as a navigator, not a captain. The navigator offers a strategic plan of movement, depending on where the captain is headed. ” At the company, Honey concentrated on engineering, and transferred control to George Bremser.

Employees mark the start of Navigator sales in 1985. Walter Zavoli is visible in the foreground in the center

On the road

The first copies of Etak Navigator went on sale in July 1985, while the 450th model sold for $ 1395 (in terms of today's bucks it is $ 3083), and the 700th for $ 1595. Cassettes with cards cost $ 35 apiece. Initially, only a map of the bay area was available, and then other major metropolitan regions followed. The system in the car for a couple of hours was installed by the same people who sold audio systems and cell phones for cars.

The navigator was so ahead of time that it became not only the first commercial navigation system for cars, but also the only one for two whole years. The system was so successful that most followers licensed company patents, card data, or hardware.

This opened up good opportunities for Etak. The consumer electronics business was challenging. For most people from the 1980s, it was quite difficult to justify buying a digital card for a car for $ 2000. But the price was not such a problem for companies that had large fleets of cars. Data from Etak cards came in handy at companies like Coca-Cola or UPS, which used them in control centers to plan the best routes.

Hani believes that Etak sold between 2,000 and 5,000 copies, with a 4.5-inch model being in demand by car drivers and a 7-inch model by truck drivers. In a downturn in sales, Etak successfully abandoned its hardware business. Working with an army of cartographers around the world, she has digitized most of the roads and other objects on the ground. The data they collected was so comprehensive and accurate that they are still used by various applications - for example, Maps from Apple.

The company realized that digital maps are not just an exercise in encoding roads and addresses. They can help you plan the best routes to business outlets. This interested Australian media mogul Rupert Murdoch. His company, News Corporation, bought Etak in 1989 for $ 25 million. Stan Honey became vice president of technology at News Corp.

Bushnel liked the result - Etak was one of his most successful investments, and a bright spot on his long summary of strange and unsuccessful, but always innovative projects.

Place of work of digitizer cartographers

Etak was resold several times in a row, at an increasing price, as the data collected by the company became more and more valuable. In 1996, Sony bought the company for $ 100 million. As a result, Etak fell into the hands of TomTom, which made sure that all the data on the cards, which began to be collected back in 1984, survived to this day.

Hani, Miles, and several of their colleagues later did other things related to navigation. They created a luminous halo around the NHL hockey puck, tracking the puck's position on the field, and digital effects for broadcasting. None of this would have happened if Hani had not been so in love with navigation and was not interested in questions and the art of navigation. Today, at the age of 60, he continues to work as a navigator in regattas held around the world.

Today, the fact that a mobile device can help you get to the point you need, which was almost unbelievable in 1985, is taken for granted by us. We do not think of it as something outstanding — but it really is. And Etak's legacy is the fact that today we are lost in the area much less than before.