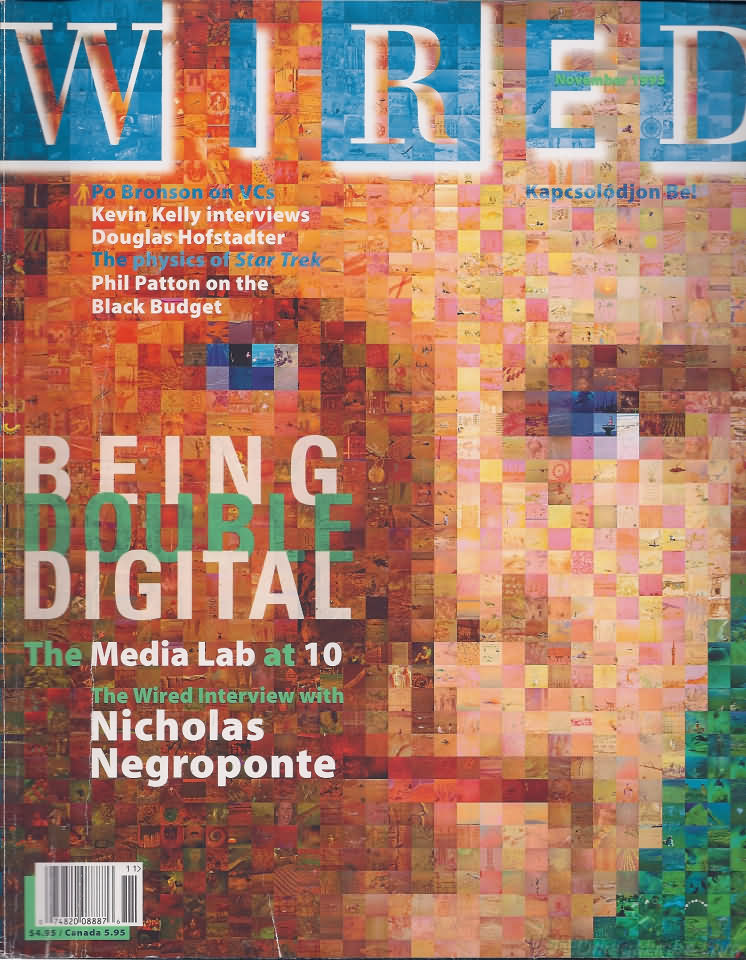

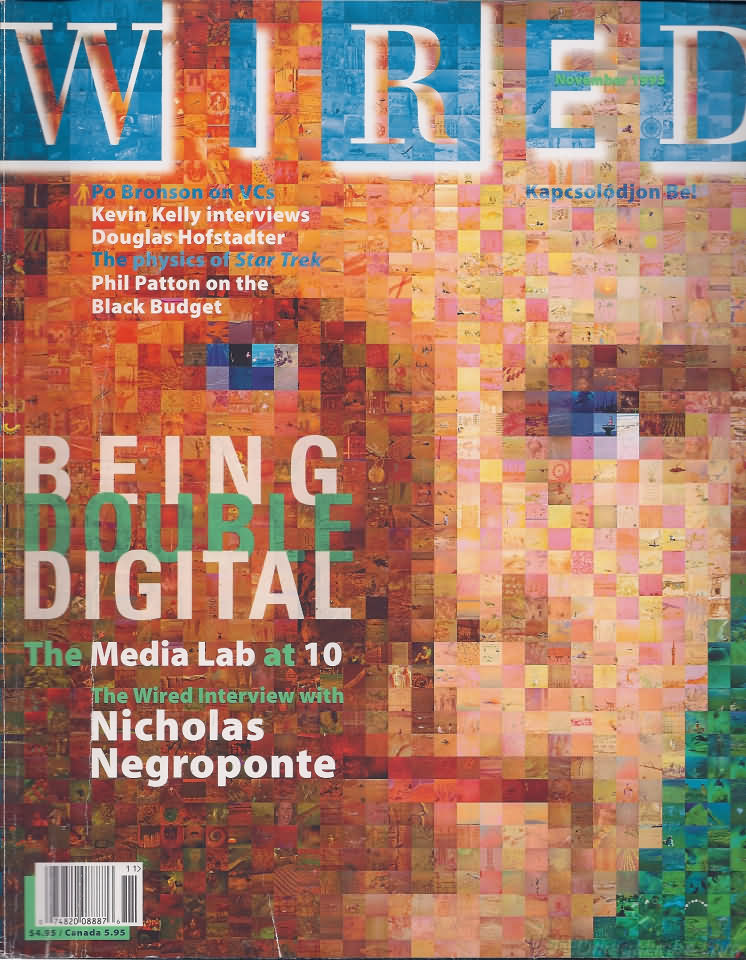

Being Digital (1995 fundamental article by Nikolos Negroponte on the digital economy, part 2)

- Transfer

The article that started the digital economy.

Message: 20

Date: 1.1.95

From:

To:

Theme: Being Digital

Part 1 .

When I agreed to write a back page for WIRED, I had no idea what this would entail. I got a lot of surprises. The biggest of them was my discovery, which is that readers of the magazine included a wide range of people, and not just those who have @ the basis of the name. When I found out that the children gave their parents WIRED as Christmas gifts, I was shocked. There seems to be a great thirst for understanding computers, electronic content and the network, not only as technology, but as culture.

For this reason, with the approval of many readers (even those who usually throw thunder and lightning), I decided to turn my WIRED speakers into a book called Digital World, which will be released on February 1. The idea sounded simple in June, but 20 stories are not necessarily easily combined into one book, even if each of them is worth its weight in gold. More importantly, a lot of things have changed so quickly that my old stories, which were trying to predict the future, have become just an old, useless hat.

To my surprise, the only thing that remained completely unchanged was that only the words were used in the columns - no images. It seems to work. As one of the inventors of multimedia, it seemed to me that I never use illustrations. Moreover, as a person who believes in bits, I had to come to terms with the idea that my publisher, Knopf, would supply simple atoms.

I learned something for myself while modeling my columns for topics that will be covered throughout the book. First, bits are bits, but all bits are not created equal. The entire economic telecommunications model, based on billing per minute, per mile or per bit, is about to fall apart. As human-to-human communications become more and more asynchronous, time will be meaningless (five hours of music will be delivered to you in less than five seconds). Distance doesn’t matter: from satellite, the distance from New York to London is only five miles greater than the distance from New York to Newark. Of course, a small portion of Gone With the Wind cannot be rated the same as a small portion of email. In fact, the expression "a small part" has a new and enormous dual meaning.

In addition, we do not know how to wield bits. Copyright law will be disintegrated. In the United States, copyrights and patents are not in the same branch of government. Copyright has very little logic: you can hum the “Happy Birthday To You” motive in people as much as your heart desires, but if you sing words, you owe it to the royal authority. Bits are really just bits. But what they stand for, who owns them, and how we interact with them is accessible to everyone.

You cannot gain experience using only a small part of anything. This object must be turned into atoms so that people can enjoy it. While the process of converting bits into atoms has become sensitive to meaning, the opposite direction — turning atoms into bits — is almost abandoned. The human contribution to the machines is paleolithic and keeps most parents and many of our friends from carrying cables.

The acute problems are speech (long overdue) and vision (usually not considered). What I understood in writing this part of the book is that we have a funny coincidence right in front of our nose (if I may say so). Many companies, especially Intel (which openly and easily express their opinions about many things), promote electronic video conferencing. The result is that sooner rather than later, we will have a growing population of cars with solid state television cameras at the top of the screen and built-in microphones at the bottom.

Although this design was designed to transfer your voice and image of your face to a remote and similar computer, it could conveniently serve as a direct channel in your computer - not just a teleconference, but rather a local conference with your machine. Therefore, please Intel, make sure that audio and video are suitable for processing, so my car sees my face and hears my voice. Sometimes I really want to be in the company of such a machine.

This is where my optimism may have interfered; I probably have too many of these O genes (optimistic). But I believe that being digital is good. This can smooth out organizations, globalize society, decentralize control, and help harmonize people without knowing whether you are a dog or a person. In fact, there is a parallel between open and closed systems and open and closed societies, which I could not describe in the book. Just as proprietary systems have led to the collapse of once-great companies such as Data General, Wang, and Prime, overly hierarchical and socially conscious societies will collapse. The nation state may disappear. And the world wins when people can compete with the imagination, and not with official position.

In addition, all digital will be less interested in race or wealth and will be more concerned about age (if specified). First World telecommunications infrastructures are progressing rapidly in developing countries and will soon become more wired (and wireless). We once wailed about the demographics of the world. But now we have to ask ourselves: taking two countries with approximately the same population, Germany and Mexico, is it really good that less than half of all Germans are under 40 and is it so bad that more than half of all Mexicans are over 20? Which of these countries will benefit from the digital world?

One of the many things that I learned is that publishers will simultaneously release an audio version of the book. I discovered this at the same time that I was informed that I would have to voice it. Since I suffer from dyslexia, even when I speak in my own words, I refused. Then I asked Knopf if Penn Gillett (see the September cover of WIRED) can do this. Penn is one of the coolest people I know, and I felt that he would bring all kinds of magic to the process. At the time when I thought Knopf abandoned this wild idea, they really managed to ask Penn before I could contact him. He kindly agreed. All he asked me via email was: “Are there any difficult words?” No, they are not.

To be continued...

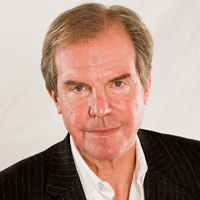

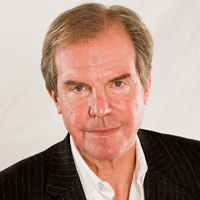

Nicholas Negroponte is an American computer scientist of Greek origin.

Nicholas Negroponte is an American computer scientist of Greek origin.

Sibling of US Under Secretary of State (2007), former Director of US National Intelligence (2005-2007) John Dimitris Negroponte.

In 1985, he founded and led Media Labs at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. From 1993 to 1998, he led the column “Move bits, not atoms” in the Wired magazine. In 1995, he formulated the concept of Digital Economics. Since 2005, he has been the initiator and leader of the 2b1 educational project, the forerunner of the UN One Laptop Per Child program (a laptop for every child). Since February 2006, he heads the non-profit organization OLPC, which was formed under the aegis of the UN.

Message: 20

Date: 1.1.95

From:

To:

Theme: Being Digital

Part 1 .

Book paradox

When I agreed to write a back page for WIRED, I had no idea what this would entail. I got a lot of surprises. The biggest of them was my discovery, which is that readers of the magazine included a wide range of people, and not just those who have @ the basis of the name. When I found out that the children gave their parents WIRED as Christmas gifts, I was shocked. There seems to be a great thirst for understanding computers, electronic content and the network, not only as technology, but as culture.

For this reason, with the approval of many readers (even those who usually throw thunder and lightning), I decided to turn my WIRED speakers into a book called Digital World, which will be released on February 1. The idea sounded simple in June, but 20 stories are not necessarily easily combined into one book, even if each of them is worth its weight in gold. More importantly, a lot of things have changed so quickly that my old stories, which were trying to predict the future, have become just an old, useless hat.

To my surprise, the only thing that remained completely unchanged was that only the words were used in the columns - no images. It seems to work. As one of the inventors of multimedia, it seemed to me that I never use illustrations. Moreover, as a person who believes in bits, I had to come to terms with the idea that my publisher, Knopf, would supply simple atoms.

Bits are bits

I learned something for myself while modeling my columns for topics that will be covered throughout the book. First, bits are bits, but all bits are not created equal. The entire economic telecommunications model, based on billing per minute, per mile or per bit, is about to fall apart. As human-to-human communications become more and more asynchronous, time will be meaningless (five hours of music will be delivered to you in less than five seconds). Distance doesn’t matter: from satellite, the distance from New York to London is only five miles greater than the distance from New York to Newark. Of course, a small portion of Gone With the Wind cannot be rated the same as a small portion of email. In fact, the expression "a small part" has a new and enormous dual meaning.

In addition, we do not know how to wield bits. Copyright law will be disintegrated. In the United States, copyrights and patents are not in the same branch of government. Copyright has very little logic: you can hum the “Happy Birthday To You” motive in people as much as your heart desires, but if you sing words, you owe it to the royal authority. Bits are really just bits. But what they stand for, who owns them, and how we interact with them is accessible to everyone.

The interface is where bits and people meet

You cannot gain experience using only a small part of anything. This object must be turned into atoms so that people can enjoy it. While the process of converting bits into atoms has become sensitive to meaning, the opposite direction — turning atoms into bits — is almost abandoned. The human contribution to the machines is paleolithic and keeps most parents and many of our friends from carrying cables.

The acute problems are speech (long overdue) and vision (usually not considered). What I understood in writing this part of the book is that we have a funny coincidence right in front of our nose (if I may say so). Many companies, especially Intel (which openly and easily express their opinions about many things), promote electronic video conferencing. The result is that sooner rather than later, we will have a growing population of cars with solid state television cameras at the top of the screen and built-in microphones at the bottom.

Although this design was designed to transfer your voice and image of your face to a remote and similar computer, it could conveniently serve as a direct channel in your computer - not just a teleconference, but rather a local conference with your machine. Therefore, please Intel, make sure that audio and video are suitable for processing, so my car sees my face and hears my voice. Sometimes I really want to be in the company of such a machine.

Digital life

This is where my optimism may have interfered; I probably have too many of these O genes (optimistic). But I believe that being digital is good. This can smooth out organizations, globalize society, decentralize control, and help harmonize people without knowing whether you are a dog or a person. In fact, there is a parallel between open and closed systems and open and closed societies, which I could not describe in the book. Just as proprietary systems have led to the collapse of once-great companies such as Data General, Wang, and Prime, overly hierarchical and socially conscious societies will collapse. The nation state may disappear. And the world wins when people can compete with the imagination, and not with official position.

In addition, all digital will be less interested in race or wealth and will be more concerned about age (if specified). First World telecommunications infrastructures are progressing rapidly in developing countries and will soon become more wired (and wireless). We once wailed about the demographics of the world. But now we have to ask ourselves: taking two countries with approximately the same population, Germany and Mexico, is it really good that less than half of all Germans are under 40 and is it so bad that more than half of all Mexicans are over 20? Which of these countries will benefit from the digital world?

And you don’t even have to read them

One of the many things that I learned is that publishers will simultaneously release an audio version of the book. I discovered this at the same time that I was informed that I would have to voice it. Since I suffer from dyslexia, even when I speak in my own words, I refused. Then I asked Knopf if Penn Gillett (see the September cover of WIRED) can do this. Penn is one of the coolest people I know, and I felt that he would bring all kinds of magic to the process. At the time when I thought Knopf abandoned this wild idea, they really managed to ask Penn before I could contact him. He kindly agreed. All he asked me via email was: “Are there any difficult words?” No, they are not.

To be continued...

about the author

Nicholas Negroponte is an American computer scientist of Greek origin.

Nicholas Negroponte is an American computer scientist of Greek origin. Sibling of US Under Secretary of State (2007), former Director of US National Intelligence (2005-2007) John Dimitris Negroponte.

In 1985, he founded and led Media Labs at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. From 1993 to 1998, he led the column “Move bits, not atoms” in the Wired magazine. In 1995, he formulated the concept of Digital Economics. Since 2005, he has been the initiator and leader of the 2b1 educational project, the forerunner of the UN One Laptop Per Child program (a laptop for every child). Since February 2006, he heads the non-profit organization OLPC, which was formed under the aegis of the UN.