Why you should give another chance to closure

In JavaScript, functions can be nested inside other functions.

A closure is when an internal function has access to the variables of the parent function, even after the parent function is executed.

As you can see, this becomes interesting when the inner function continues to exist in the call to the parent function. This will happen in the following situations:

- an internal function is used as a call for an asynchronous task, such as a timer, event, or AJAX.

- the parent function returns an internal function or object that stores the internal function.

Closing and timers

In the following example, we expect the local variable x to be destroyed immediately after the autorun () function is executed , but it will be alive for 10 minutes. This is because the variable x is used by the internal function log () . The log () function is a closure.

(function autorun(){

var x = 1;

setTimeout(function log(){

console.log(x);

}, 6000);

})();When setInterval () is used , the variable referenced by the closure function will only be destroyed after clearInterval () is called .

Closure and events

We create closures every time variables from external functions are used in event handlers. The increment () event handler is a closure in the following example.

(function initEvents(){

var state = 0;

$("#add").on("click", function increment(){

state += 1;

console.log(state);

});

})();Closing and Asynchronous Tasks

When variables from an external function are used in an asynchronous call, the call becomes a closure, and the variables remain active until the asynchronous task completes.

Timers, events, and AJAX calls are probably the most common asynchronous tasks, but there are other examples: HTML5 Geolocation API, WebSockets API, and requestAnimationFrame ().

In the following AJAX example, the call to updateList () is a closure.

(function init(){

var list;

$.ajax({ url: "https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users"})

.done(function updateList(data){

list = data;

console.log(list);

})

})();Short circuit and encapsulation

Another way to see a closure is with a private state function. A short circuit encapsulates a state.

For example, let's create a count () function with a private state. Each time it is called, it remembers its previous state and returns the next consecutive number. The state variable is private, there is no access to it from the outside.

function createCount(){

var state = 0;

return function count(){

state += 1;

return state;

}

}

var count = createCount();

console.log(count()); //1

console.log(count()); //2We can create many closures that share the same private state. In the following example, increment () and decrement () are two closures that share the same private state variable. Thus, we can create objects with a private state.

function Counter(){

var state = 0;

function increment(){

state += 1;

return state;

}

function decrement(){

state -= 1;

return state;

}

return {

increment,

decrement

}

}

var counter = Counter();

console.log(counter.increment());//1

console.log(counter.decrement());//0Short circuit against pure functions

Closing is used by variables from the outer scope.

Pure functions do not use variables from the outer scope. Pure functions should return a value calculated using only the values passed to it, and there can be no side effects.

Asynchronous tasks: closure and loops

In the following example, I will create five closures for five asynchronous tasks, all using the same variable i . Since the variable i changes during the cycle, all console.log () display the same value - the last.

(function run(){

var i=0;

for(i=0; i< 5; i++){

setTimeout(function logValue(){

console.log(i); //5

}, 100);

}

})();One way to fix this problem is to use IIFE (Immediately Invoked Function Expression). In the following example, there are five more closures, but more than five different variables i .

(function run(){

var i=0;

for(i=0; i<5; i++){

(function autorunInANewContext(i){

setTimeout(function logValue(){

console.log(i); //0 1 2 3 4

}, 100);

})(i);

}

})();

Another option is to use a new way of declaring variables: through let , which is available as part of ECMAScript 6. This will allow you to create a variable locally for the scope of the block at each iteration.

(function run(){

for(let i=0; i<5; i++){

setTimeout(function logValue(){

console.log(i); //0 1 2 3 4

}, 100);

}

})();I believe this is the best option for this problem in terms of readability.

Short circuit and garbage collector

In JavaScript, local function variables will be destroyed after the function returns, if there are no links to them. The private state of the circuit becomes suitable for garbage collection after the circuit itself has been removed. To make this possible, a closure should no longer have a reference to it.

In the following example, I first create an add () closure

function createAddClosure(){

var arr = [];

return function add(obj){

arr.push(obj);

}

}

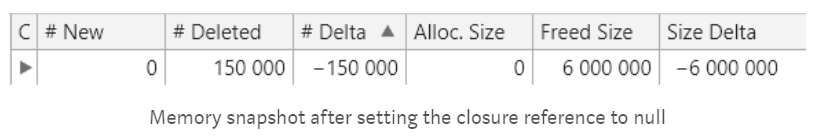

var add = createAddClosure();Then I define two functions: one to add a large number of objects addALotOfObjects () and another clearAllObjects () to specify a null reference . Then both functions are used as event handlers.

function addALotOfObjects(){

for(let i=0; i<50000;i++) {

add({fname : i, lname : i});

}

}

function clearAllObjects(){

if(add){

add = null;

}

}

$("#add").click(addALotOfObjects);

$("#clear").click(clearAllObjects);Clicking Add will add 50,000 items to the private lock state.

I clicked “Add” three times and then clicked “Clear” to set the null link . After that, the private state is cleared.

Conclusion

Closure is the best tool in our encapsulation tool box. It also simplifies our work with calls for asynchronous tasks. We just use the variables we want and they will come to life at the time of the call.

On the other hand, it’s very useful to understand how closures work to make sure that the closure will be removed during garbage collection when we no longer need them.

This is arguably the best functionality ever put into a programming language.

Douglas Crockford on closure.