“Invisible design”: we design together with machines

- Transfer

- Recovery mode

Irina Cherepanova and Tatyana Zhukova from the uKit AI project , which teaches neural networks to website design, have translated Amber Cartwright’s product manager’s product designer’s team column from Airbnb on how smart technologies can improve well-known products.

The car was and remains my constant partner. With it, I transform creative thoughts into a tangible product that I can share with the world. When I was 20 and I came to design, leaving my career in modern dance, I could not think that the machine would be my assistant in creating breakthrough products.

Nowadays, machine intelligence is rapidly developing, and after it the methods and products that we design should evolve. Here is a story about designing in tandem with machines, or, as I call it, about “invisible design”: working with artificial intelligence and machine learning. Tools that, in my opinion, create fertile ground for future product design.

Take an example from the past: an English gentleman walks around the garden at the beginning of the 18th century and watches an apple fall from a tree. He wonders why it did not fall to the side or bounce up from the ground. How is this possible? What forces are involved? What is their nature? Does this phenomenon equally apply to small items like apples and large ones like carts? Sir Isaac Newton dealt with these issues for over 20 years and deduced the law of gravity. He was able to describe an invisible force that tangibly affects our daily lives.

Recently, looking through the Facebook feed, I noticed that several of my friends liked the company, which offered to design and order individual frames for posters and canvases online. I thought about all those unframed works that were in my pantry, and clicked to see what they were offering. Why am I interested in this recommendation? What caught my attention? What kind of information did they use to personalize this post? The invisible forces of science and mathematics involved here are social network algorithms. Adware is just the germinal state of the possibilities that machine learning brings in the next 5–10 years.

I began to comprehend the essence of this “invisible design” on Airbnb when we launched products that required processing a large amount of data. And I would like to share some observations from my practice.

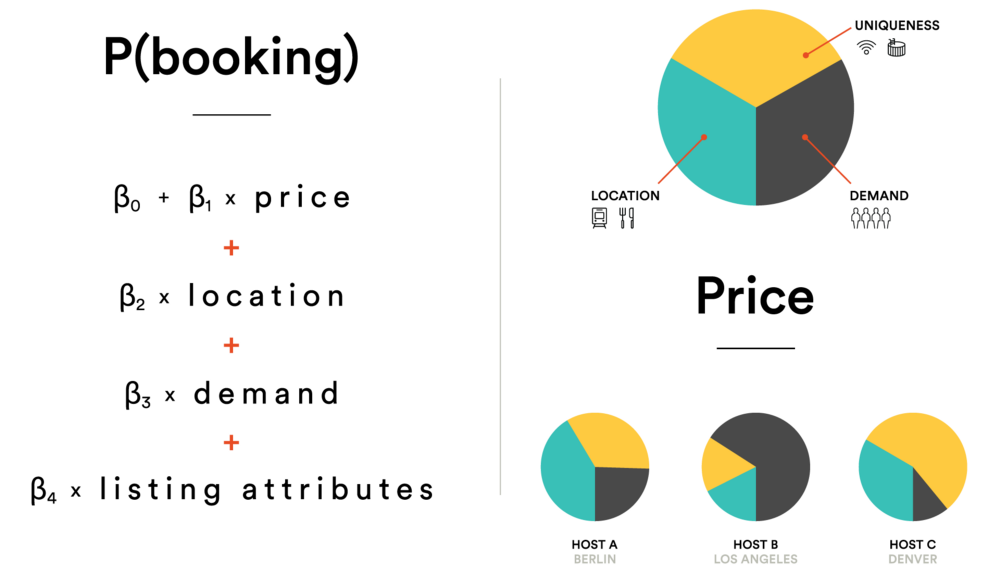

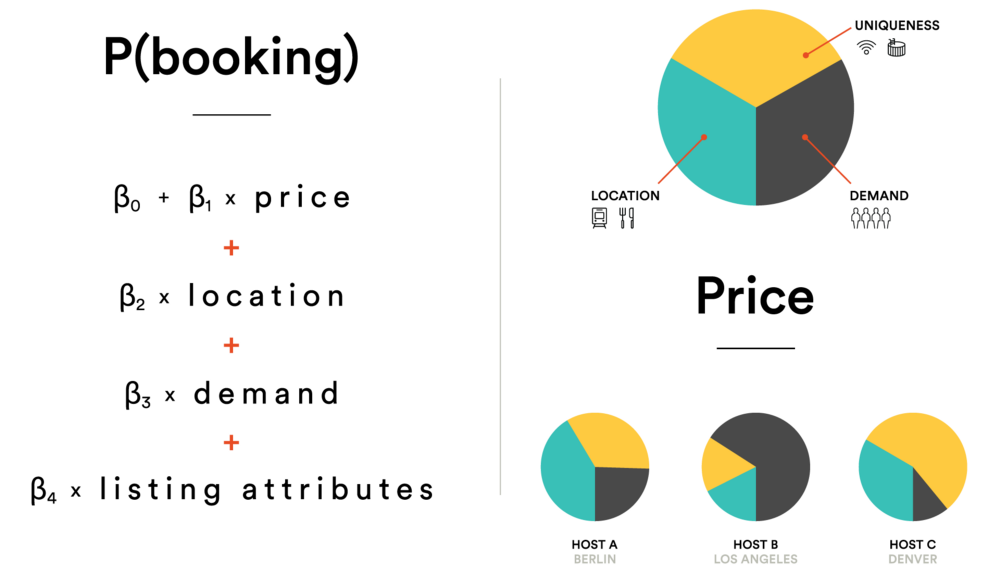

Last year, the product team and I discussed a machine learning model for a new pricing tool that homeowners wanted to offer. We tried to create a model that would answer the question: “What will be the rental price at some point in the future?” Finding an answer was not a trivial task. I tried to keep up while my data processing partner described the regression model they were building.

He showed sketches and rushed with clever words, and although I could catch the idea, the terminology was unusual for me as a designer. After that, I asked him to outline the model diagram and discuss all the details again. This conversation was a revelation for me. When he spoke in a language familiar to me - having illustrated the data in diagrams and diagrams - I instantly understood the model and its goals. At that moment, my light came on. I realized how valuable the machine is for the product and how to use the information received in the design of user interaction.

We were both encouraged to come to this understanding, and when the language barrier was broken, we were able to freely talk about the prospects for the development of the product. The discussion has unfolded at a new level.

A smart model of price regression and its visualization: the model consists of three parts, which vary depending on the host's offer and market demand.

I realized that the experience gained from this conversation can be extrapolated to our teams. This discussion was only a tiny part of the big story; part comparable to the moment when we do the first draft of the screens in the notebook. I realized that the history of the product does not come down to screens that users can see and touch. She also describes what happens “behind the scenes”.

At the initial stages of product creation, as a rule, a supporting story is built up - it describes the end-user experience so that each team member has an understanding of the appearance and behavior of the product. Various forms are used - from storyboards to prototypes, presentations of strategies and diagrams. These presentations are created for many reasons, but the most important is the formation of a common vision for the product.

Understanding the product increases the potential of the team. General knowledge allows innovations not only to move forward, but to go by leaps and bounds.

When we have an understanding of what we are designing and how it should work, we begin to create a product, with each using its own arsenal of tools. The carpenter has a hammer. The photographer has a camera. The product designer has a sketch. The developer has a code. It is interesting that only the last, our partner in the workshop, has a tool that can learn, change and develop over time.

Invisible Design adds data and algorithmic solutions to the initial stages of design — wireframes and behavioral scenarios — bringing multidimensionality to the usually flat and static stage of product creation.

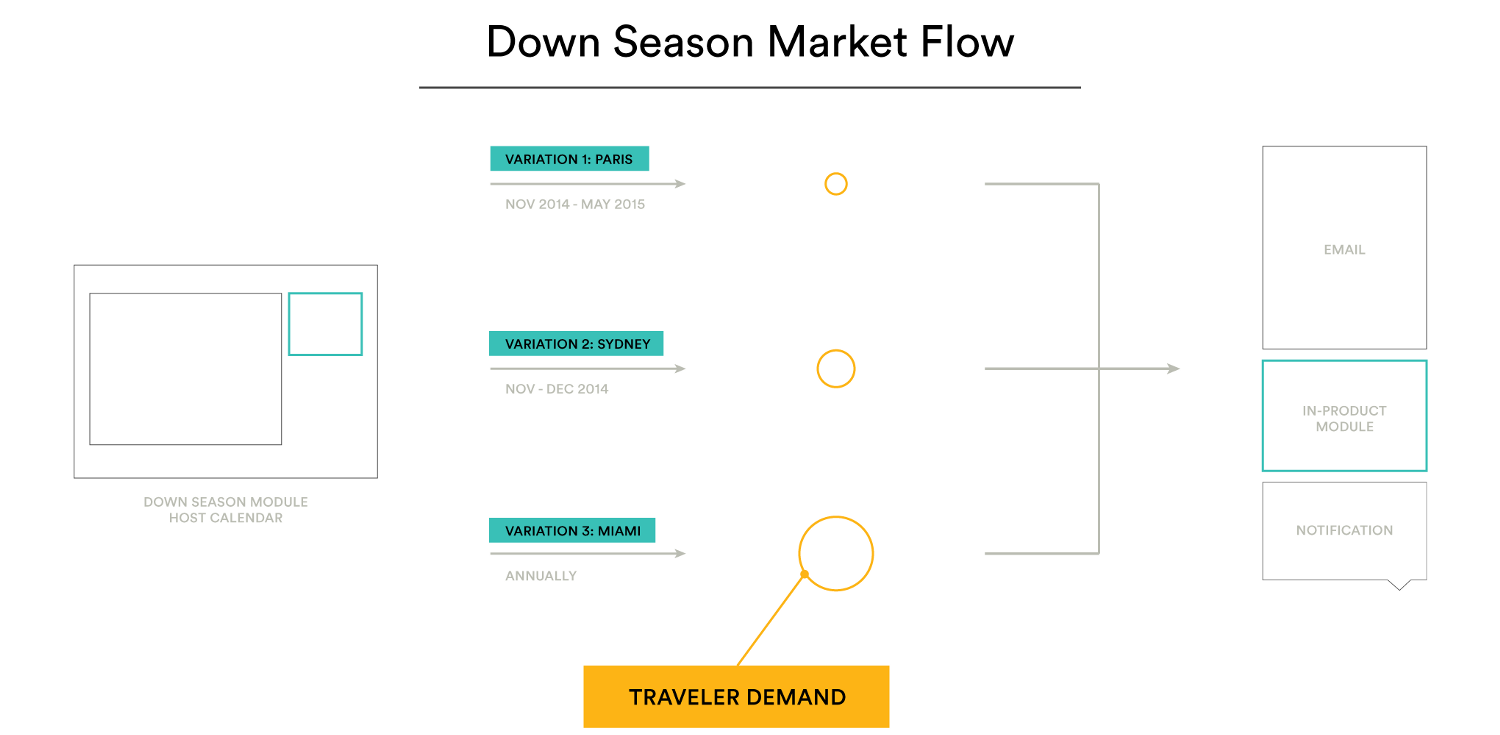

Take, for example, pricing tips for homeowners on Airbnb. This was the first iteration of our Smart Prices product: pricing recommendations for the New Year holidays. From the data on the last winter vacation season, we knew that usually people travel less in the last two weeks of December, and we observed a sharp jump in travel closer to the New Year. And they wanted to inform our community of landlords that if you lower prices at a certain moment, you can attract more guests.

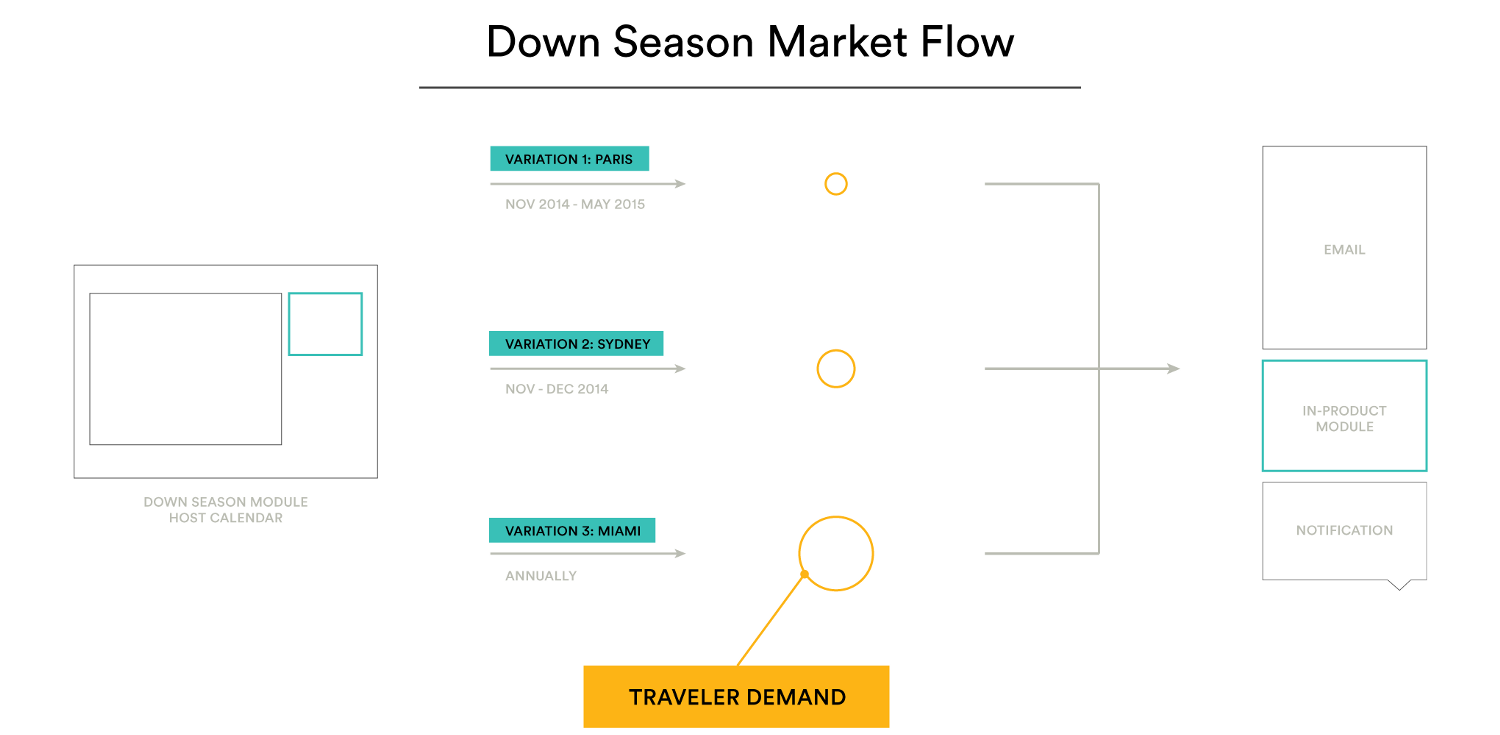

From the data model, we found that markets differ from each other depending on dead seasons. They needed different messages and visualizations: for example, in Sydney, the downtime period begins in November, and in Miami there is no dead season at all due to constant demand.

Our scenarios and wireframes, originally implemented in one module, after processing were able to show how market trends and statistical data will affect the product.

Example: market dynamics cause the desired variations of modules and messages to be shown.

When we make a product for an international audience (which means a difference in needs), we are at the same time constantly searching for typical solutions that will help us achieve simplicity and understanding of the product, despite the difficulties. Visualization of scenarios and demand allowed us to see not just a handful of modules, but the entire communication system.

I was honored to work together with incredibly talented designers, the best masters of their craft, but not only they are characterized by a creative approach. The approach of data processing specialists to business is in itself an art form. Creating models and hypotheses about human behavior based on sets of information has opened my eyes to one important thing: human behavior is not trivial, and you cannot design the experience of interacting with a product in isolation, within only one design team.

For many years I worked at an agency where teams existed separately from each other: designers in one department, developers in another. When I arrived at Airbnb, things were similar. For 100+ developers, there were only ten designers. Colossal imbalance. But the staff was expanding, and the vice president formed a steering group, which consisted of a design manager (it's me), a product manager, the head of the statistics department, as well as technical and financial managers. My view of the world began to change. I participated in discussions, which I had not been involved in before, and we made joint decisions, taking into account the tasks and needs of the teams that we represented. I learned how other “worlds” work, and how to use the knowledge and skills of my colleagues to improve the product.

It is important to adhere to this rule in order for the “invisible design” to work. In some companies, programmers make their fate, in others the king is the product manager, in others the designers command the parade. But very rarely, leading departments work in tandem, jointly determining the strategy and respecting the decisions that are in the competence of colleagues. Sometimes it’s useful to “face off” - it turns out to be a damn good product.

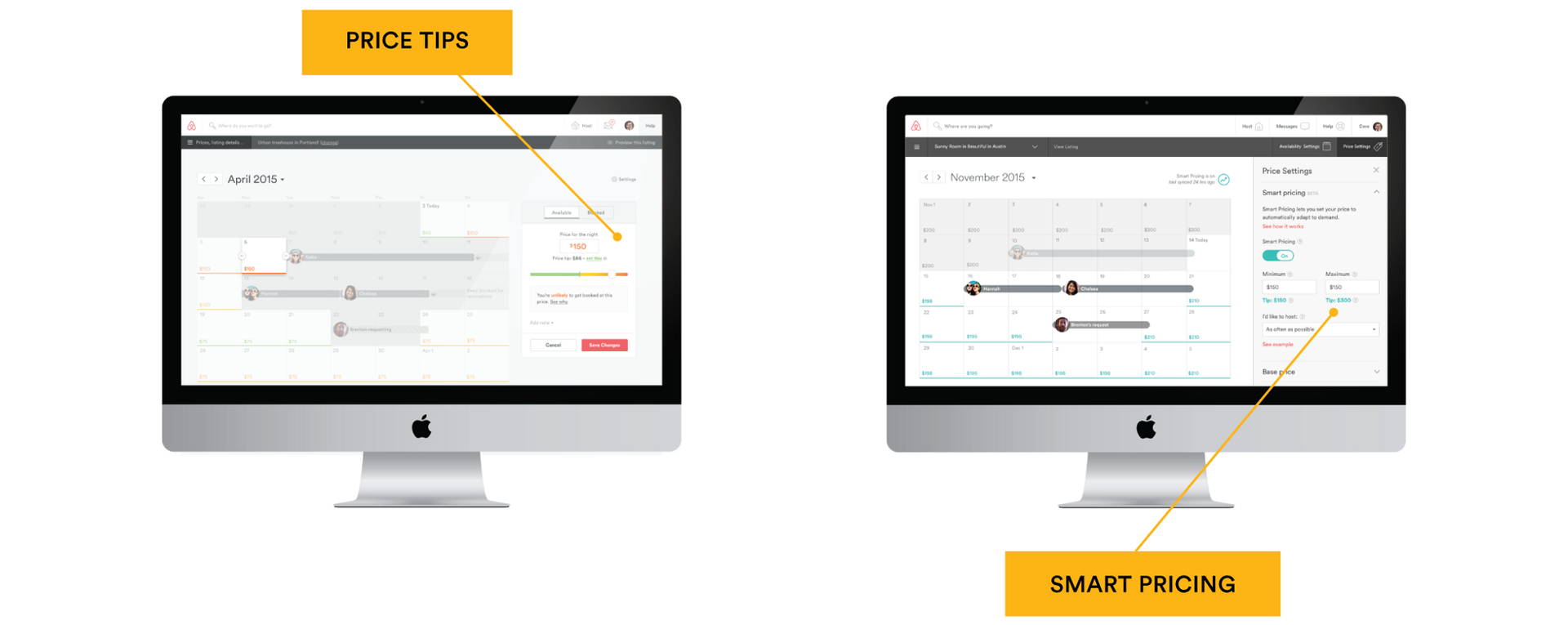

The “Smart Prices” function, when the algorithmic model advised apartment owners, what rental price is best set for a particular day, is an example of how the composition of the team helped develop the product.

Initially, the product could automatically correct prices, and we thought that this would be a great solution for apartment owners, because you do not have to adjust prices every day. However, examining the results, we learned that some landlords want to set a rental ceiling regardless of market demand: it would seem that with a price in the market you can earn more, but one segment had its own idea of how much it is reasonable to rent out your lodging for guests.

When the model worked for some time, we needed to adjust it, taking into account the quality information that we collected - the opinions of the homeowners - and enter them into the interface.

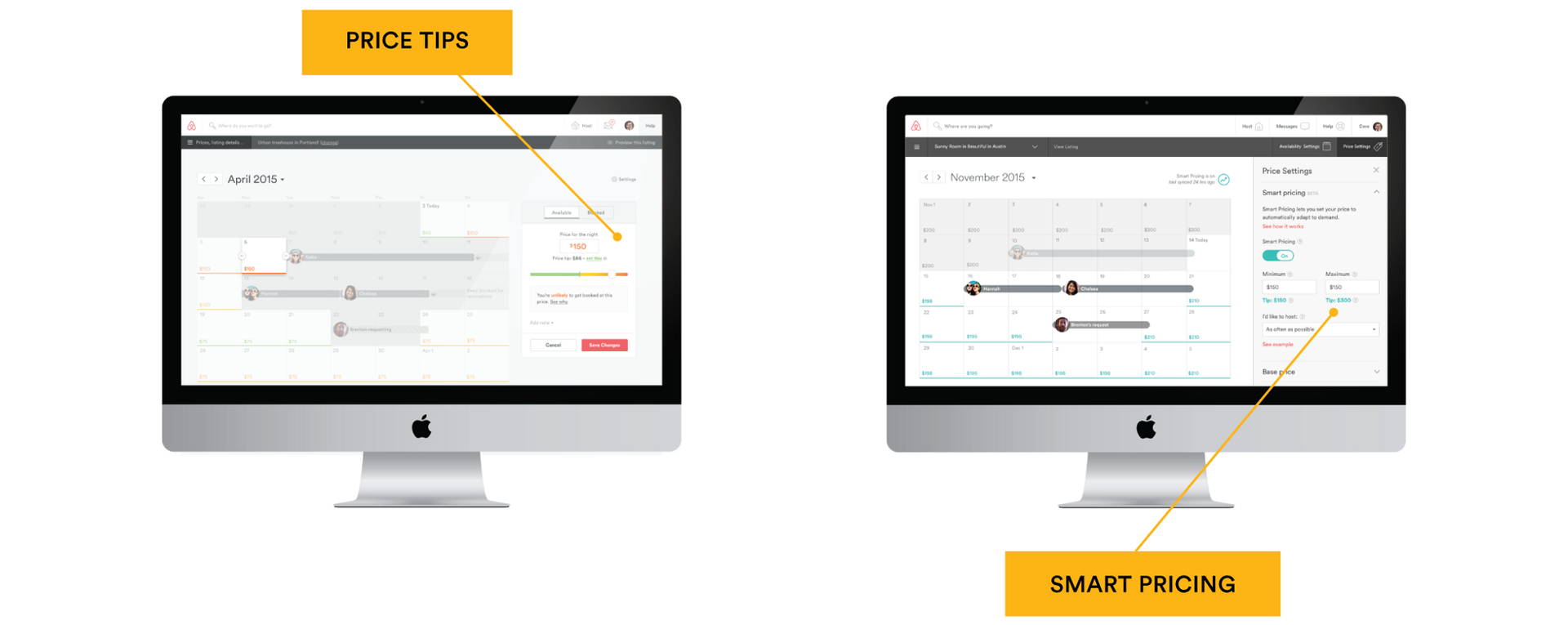

At the output, we received a product supersuccessful in terms of satisfying user and information needs: landlords got more control mechanisms - were able to set minimum and maximum prices, as well as choose the desired frequency of reception of guests. Below you can follow the evolution of the first version of Pricing Tips to our current Smart Pricing feature.

“Price tips” were a simple interpretation of the model - you adjust the price and see how likely your apartment is being rented. If the landlord activated the price tips for the month, it was impossible to flexibly set the upper threshold for the amounts, except to manually set your price for each specific day. Our latest version of Smart Prices allows you to set prompts for up to four months and has finer settings for minimum and maximum prices, thereby providing controls and functionality that homeowners find useful.

Smart Landlords liked many landlords, and this is the result of the fact that representatives of different departments were included in the work, arranged the necessary discussions when circumstances required it.

These thoughts are just a prologue to conversations about "invisible design." I will continue to research and write about my discoveries - about understanding tasks and ways to solve them, about using tools and analyzing results - as I move further along the path of product design. To get acquainted with how “invisible design” is developing in practice, see the detailed analysis of the user scenario of the “Smart Prices” functionality, which I presented at the IxDA conference in Helsinki earlier this year.

1. Free software for UI / UX and design:

2. The program "Big Data: the basics of working with large data sets"

For whom: engineers, programmers, analysts, marketers, designers - everyone who is just starting to delve into the technology of Big Data.

Training format: online

Details on the link →

The car was and remains my constant partner. With it, I transform creative thoughts into a tangible product that I can share with the world. When I was 20 and I came to design, leaving my career in modern dance, I could not think that the machine would be my assistant in creating breakthrough products.

Nowadays, machine intelligence is rapidly developing, and after it the methods and products that we design should evolve. Here is a story about designing in tandem with machines, or, as I call it, about “invisible design”: working with artificial intelligence and machine learning. Tools that, in my opinion, create fertile ground for future product design.

Mathematics and science are invisible forces that reveal themselves more and more and affect our lives.

Take an example from the past: an English gentleman walks around the garden at the beginning of the 18th century and watches an apple fall from a tree. He wonders why it did not fall to the side or bounce up from the ground. How is this possible? What forces are involved? What is their nature? Does this phenomenon equally apply to small items like apples and large ones like carts? Sir Isaac Newton dealt with these issues for over 20 years and deduced the law of gravity. He was able to describe an invisible force that tangibly affects our daily lives.

Recently, looking through the Facebook feed, I noticed that several of my friends liked the company, which offered to design and order individual frames for posters and canvases online. I thought about all those unframed works that were in my pantry, and clicked to see what they were offering. Why am I interested in this recommendation? What caught my attention? What kind of information did they use to personalize this post? The invisible forces of science and mathematics involved here are social network algorithms. Adware is just the germinal state of the possibilities that machine learning brings in the next 5–10 years.

Machines will increasingly make decisions based on user experience, and designing in tandem with them is the key to the future of product design.

I began to comprehend the essence of this “invisible design” on Airbnb when we launched products that required processing a large amount of data. And I would like to share some observations from my practice.

Last year, the product team and I discussed a machine learning model for a new pricing tool that homeowners wanted to offer. We tried to create a model that would answer the question: “What will be the rental price at some point in the future?” Finding an answer was not a trivial task. I tried to keep up while my data processing partner described the regression model they were building.

He showed sketches and rushed with clever words, and although I could catch the idea, the terminology was unusual for me as a designer. After that, I asked him to outline the model diagram and discuss all the details again. This conversation was a revelation for me. When he spoke in a language familiar to me - having illustrated the data in diagrams and diagrams - I instantly understood the model and its goals. At that moment, my light came on. I realized how valuable the machine is for the product and how to use the information received in the design of user interaction.

We were both encouraged to come to this understanding, and when the language barrier was broken, we were able to freely talk about the prospects for the development of the product. The discussion has unfolded at a new level.

A smart model of price regression and its visualization: the model consists of three parts, which vary depending on the host's offer and market demand.

I realized that the experience gained from this conversation can be extrapolated to our teams. This discussion was only a tiny part of the big story; part comparable to the moment when we do the first draft of the screens in the notebook. I realized that the history of the product does not come down to screens that users can see and touch. She also describes what happens “behind the scenes”.

At the initial stages of product creation, as a rule, a supporting story is built up - it describes the end-user experience so that each team member has an understanding of the appearance and behavior of the product. Various forms are used - from storyboards to prototypes, presentations of strategies and diagrams. These presentations are created for many reasons, but the most important is the formation of a common vision for the product.

Understanding the product increases the potential of the team. General knowledge allows innovations not only to move forward, but to go by leaps and bounds.

The visualization of the roles that machines and statistics play in learning is the first part of “invisible design”.

When we have an understanding of what we are designing and how it should work, we begin to create a product, with each using its own arsenal of tools. The carpenter has a hammer. The photographer has a camera. The product designer has a sketch. The developer has a code. It is interesting that only the last, our partner in the workshop, has a tool that can learn, change and develop over time.

Invisible Design adds data and algorithmic solutions to the initial stages of design — wireframes and behavioral scenarios — bringing multidimensionality to the usually flat and static stage of product creation.

Take, for example, pricing tips for homeowners on Airbnb. This was the first iteration of our Smart Prices product: pricing recommendations for the New Year holidays. From the data on the last winter vacation season, we knew that usually people travel less in the last two weeks of December, and we observed a sharp jump in travel closer to the New Year. And they wanted to inform our community of landlords that if you lower prices at a certain moment, you can attract more guests.

From the data model, we found that markets differ from each other depending on dead seasons. They needed different messages and visualizations: for example, in Sydney, the downtime period begins in November, and in Miami there is no dead season at all due to constant demand.

Our scenarios and wireframes, originally implemented in one module, after processing were able to show how market trends and statistical data will affect the product.

Example: market dynamics cause the desired variations of modules and messages to be shown.

When we make a product for an international audience (which means a difference in needs), we are at the same time constantly searching for typical solutions that will help us achieve simplicity and understanding of the product, despite the difficulties. Visualization of scenarios and demand allowed us to see not just a handful of modules, but the entire communication system.

True mastery comes with the experience and development of an individual style, and this quality is inherent exclusively to people. Not a single machine has yet learned to express individual creative design and artistic views.

I was honored to work together with incredibly talented designers, the best masters of their craft, but not only they are characterized by a creative approach. The approach of data processing specialists to business is in itself an art form. Creating models and hypotheses about human behavior based on sets of information has opened my eyes to one important thing: human behavior is not trivial, and you cannot design the experience of interacting with a product in isolation, within only one design team.

For many years I worked at an agency where teams existed separately from each other: designers in one department, developers in another. When I arrived at Airbnb, things were similar. For 100+ developers, there were only ten designers. Colossal imbalance. But the staff was expanding, and the vice president formed a steering group, which consisted of a design manager (it's me), a product manager, the head of the statistics department, as well as technical and financial managers. My view of the world began to change. I participated in discussions, which I had not been involved in before, and we made joint decisions, taking into account the tasks and needs of the teams that we represented. I learned how other “worlds” work, and how to use the knowledge and skills of my colleagues to improve the product.

Specialists from each department must be present in the product team to make key decisions together.

It is important to adhere to this rule in order for the “invisible design” to work. In some companies, programmers make their fate, in others the king is the product manager, in others the designers command the parade. But very rarely, leading departments work in tandem, jointly determining the strategy and respecting the decisions that are in the competence of colleagues. Sometimes it’s useful to “face off” - it turns out to be a damn good product.

The “Smart Prices” function, when the algorithmic model advised apartment owners, what rental price is best set for a particular day, is an example of how the composition of the team helped develop the product.

Initially, the product could automatically correct prices, and we thought that this would be a great solution for apartment owners, because you do not have to adjust prices every day. However, examining the results, we learned that some landlords want to set a rental ceiling regardless of market demand: it would seem that with a price in the market you can earn more, but one segment had its own idea of how much it is reasonable to rent out your lodging for guests.

When the model worked for some time, we needed to adjust it, taking into account the quality information that we collected - the opinions of the homeowners - and enter them into the interface.

Having come together - behavior researchers, designers, product managers, developers, data analysis specialists - we were able to quickly change the course of the product strategy.

At the output, we received a product supersuccessful in terms of satisfying user and information needs: landlords got more control mechanisms - were able to set minimum and maximum prices, as well as choose the desired frequency of reception of guests. Below you can follow the evolution of the first version of Pricing Tips to our current Smart Pricing feature.

“Price tips” were a simple interpretation of the model - you adjust the price and see how likely your apartment is being rented. If the landlord activated the price tips for the month, it was impossible to flexibly set the upper threshold for the amounts, except to manually set your price for each specific day. Our latest version of Smart Prices allows you to set prompts for up to four months and has finer settings for minimum and maximum prices, thereby providing controls and functionality that homeowners find useful.

Smart Landlords liked many landlords, and this is the result of the fact that representatives of different departments were included in the work, arranged the necessary discussions when circumstances required it.

These thoughts are just a prologue to conversations about "invisible design." I will continue to research and write about my discoveries - about understanding tasks and ways to solve them, about using tools and analyzing results - as I move further along the path of product design. To get acquainted with how “invisible design” is developing in practice, see the detailed analysis of the user scenario of the “Smart Prices” functionality, which I presented at the IxDA conference in Helsinki earlier this year.

About Netology courses

1. Free software for UI / UX and design:

- "Fundamentals of graphic design: composition, color, typography"

- Adobe XD: The Basics for an Interface Designer

2. The program "Big Data: the basics of working with large data sets"

For whom: engineers, programmers, analysts, marketers, designers - everyone who is just starting to delve into the technology of Big Data.

Training format: online

Details on the link →