DIY DI in Ruby

There was already an article on Habr dedicated to Dependency Injection in Ruby, but the emphasis was more on the use of the IoC-container pattern using the dry-container and dry-auto_inject gems . But in order to take advantage of dependency injection, it is completely unnecessary to fence containers or connect libraries. Today I’ll talk about how to quickly implement DI with your own hands .

Description of Approach

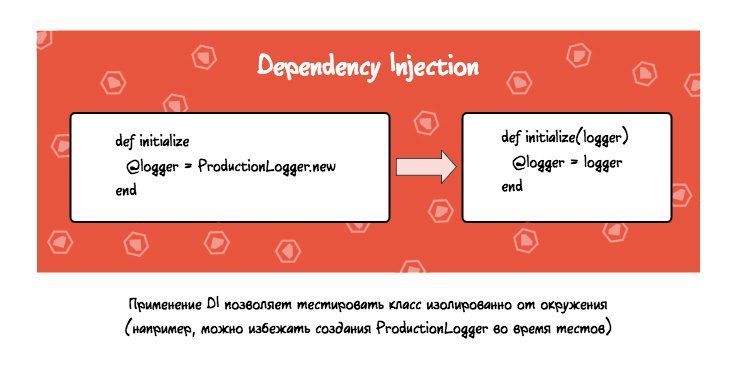

What do people use DI for? Usually in order to change the behavior of the code during tests, avoiding calls to external services or just to test the object in isolation from the environment. Of course, DHH says that we can stopTime.now and enjoy the green points of the tests without unnecessary gestures, but do not blindly believe everything that DHH says. Personally, I like the point of view of Piotr Solnica presented in this post . He gives an example:

class Hacker

def self.build(layout = 'us')

new(Keyboard.new(layout: layout))

end

def initialize(keyboard)

@keyboard = keyboard

end

# stuff

endThe parameter keyboardin the constructor is dependency injection. This approach allows you to test the class Hackerby passing Keyboardmoki instead of the real instance . Isolation, all things:

describe Hacker do

let(:keyboard) { mock('keyboard') }

it 'writes awesome ruby code' do

hacker = Hacker.new(keyboard)

# some expectations

end

endBut what I like about the example above is an elegant trick with the method .buildin which the keyboard is initialized. In the DI discussions, I saw a lot of tips that suggested initializing dependencies into the calling code, such as controllers. Yeah, and then search the entire project for Hacker occurrences to see which particular class is used for the keyboard, well. Whether business .build: default usecase in a conspicuous place, it is not necessary to search for anything.

Caller Code Testing

Consider the following example:

class ExternalService

def self.build

options = Config.connector_options

new(ExternalServiceConnector.new(options))

end

def initialize(connector)

@connector = connector

end

def accounts

@connector.do_some_api_call

end

end

class SomeController

def index

authorize!

ExternalService.build.accounts

end

endIt can be seen that the controller creates the ExternalService using real objects (although this is hidden in the method ExternalService.build), which we try to avoid by introducing DI. How to cope with this situation?

- Do not test the calling code at all. So-so option, I decided to write it down to complete the picture.

Replace

ExternalService.build. In fact, what DHH was talking about, but there is one important point:.buildwhen replacing , we do not change the behavior of the class instances, only the wrapper. RSpec example:connector = instance_double(ExternalServiceConnector, do_some_api_call: []) allow(ExternalService).to receive(:build) { ExternalService.new(connector) }- Test controllers using integration tests on a CI server. Pros: production code is tested, increasing the likelihood that potential users will catch the potential bug, not users. Cons: it is more difficult to test exceptional situations ("a third-party service has crashed") and third-party services do not always have a sandbox account on which you can safely run tests.

- Use the same IoC containers.

It seems to me that the combination of the second and third approaches is most effective: using the second, we test exceptional situations, with the help of the third, we make sure that there are no errors in the code that instantiates the objects.

conclusions

Despite the above, I am not against the use of IoC containers in general; it’s just useful to remember that there are alternatives.

Links used in the post: