The Medianomics of Long Dying: Kodak, Sears, and Newspapers

- Transfer

How are US newspapers compared to well-known companies using the old business model? The numbers do not console.

None of the inhabitants of the old Olympus is insured. Just a few weeks ago, Kodak and Sears fell into the bad news again. How many of these companies are already dying? Yes, once upon a time it was very strange to hear that digital devices compete with Kodak, and that Walmart, Target, Kohl and a little later, Amazon also complicate the life of America’s largest retail chains.

Would you ask an American in 1990 if he could imagine a world without Kodak? Or a simple buyer without Sears. And now it is becoming a reality. These are slowly disappearing companies, agonizing day after day. And we, of course, immediately recall the newspaper industry. And the question is the same: can you imagine a world without newspapers? But now, when tablets have been on the market for two years, making it much easier. I always laughed when they asked me if there would be newspapers in 2015 or 2020. Papyrus is with us for a long time. And the figure simply quickly supplants the press, simultaneously changing the landscape and the rules of the game in the media business and journalism. This or that press will be with us until the end of our days, but the more printers will resign, the more it will be on the side for the growing momentum of digital media.

We are used to thinking of changes in the world as a switch. Either one or the other. In fact, the world is changing both slowly and quickly.

Let's call the slow extinction of well-known media brands the medianomics of long dying. Take for example companies that are deeply impressed with our culture, habits and our wallet. Their disappearance from our lives is like the slow movement of a glacier. But this slowness does not mean that extinction does not occur. The fact that over time newspapers and partly magazines disappear is a fact. We can bet how quickly they continue to fade. By continuing, I mean a 44% drop in the use of the print press (75-80% of them are newspapers) over the past 4 years according to The Reel Time Report . (For additional numbers, refer toAlan Mutter, Leading Column at E&P ).

So there is no doubt - dying is really and slowly. Sometimes, of course, here and there, a headline of the type “Cinema cuts the production of films for silent films” flickers, as in the recent new silent film “The Artist” . (Maybe someday we will talk about the “new printing”?)

But we ask ourselves: What connects Kodak, Sears and newspapers? What can be useful from comparison?

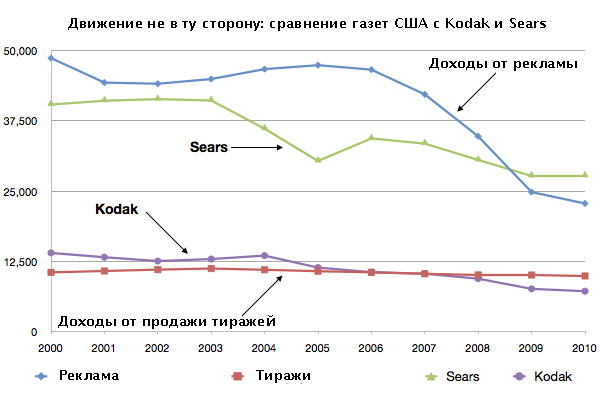

As for profitability, look at the chart. I showed the earnings of Kodak, Sears, and all US daily newspapers until 2010. Data for 2011 has not yet been received, but the year was not kind to any of these companies in any case.

Figures are in millions. Newspapers refers to the gross income of all US daily newspapers. Circulation figures for 2010 are tentative.

Most obvious is the fact that the drop in revenue for US newspapers is much greater than the drop in revenue for Kodak and Sears. Indeed, while Kodak and Sears, as unfortunate heirs to the old business, are doing poorly, then newspapers, judging by the main source of income, are even worse.

Over the period shown, newspaper revenue from advertising fell 53%, while Kodak's total revenue fell only 49%. Sears fell by 31%.

Circulations - an ace of trump cards to which newspapers could always appeal - have declined relatively over the past decade - by 6%. Circulations continued to plummet, but the continued rise in newspaper prices offset this. The sale of circulation is approximately 30% of the income of all US daily newspapers, that is, it is significant, but insufficient to compensate for the loss of revenue from the sale of advertising.

If we add the revenue from advertising and circulation, then over the decade, newspapers have lost 45% of their revenue base, i.e. just 4% less than Kodak.

Stock prices will show roughly the same when investors, poorly aware of the long dying, reach out.

What connects our three heroes? Digital news pioneer Steve Yelvington shared similar thoughts about the Kodak Newspaper pair this week, noting, among other things, that “brands are decaying,” and “the destruction is not in one fell swoop.”

Extend the metaphor. Remember the “Kodak Photo Spots” signs telling tourists to take photos at this place, exactly the same as tens of thousands of other tourists did here before? We put the owner of the newspaper (or the buyer) here, imagining that there has recently been a huge amount of sales, and see what they can say about the surrounding landscape.

The review is crucial. Why? Because, although we say that newspapers are dying, but at the same time we shout: long live the news! Those who own - buy or create a news franchise - still have time to dodge and get a lesson. History is not fate. The Kodak / Sears story is just a cautionary tale from which to draw conclusions, a time-lapse shot of the crash.

Based on the foregoing, let me offer you five deeply practical tips for media managers in 2012:

- Do not believe your own accounting reports. Public companies carefully verify the numbers, consulting with analysts and shareholders as politicians. But very often they begin to believe in the created image. Talking about the future of megastores, photography or the role of the newspaper in people's lives does not solve the main problems. Better turn to those small experts who scream loudly that time is ticking and the old business model will go to hell sooner rather than later.

- Cost reduction ≠ innovation. Just huh? Nonetheless, Sears chairman of the board of directors, Eddie Lampert , whom the business press called a wizard when he took office in 2005, cuts, lowers, and cuts costs again, turning Sears' storefront areas into moonlight. Most newspapers cut costs so much that they had no power left for mobile apps, HTML5, and digital distribution. Innovation means at the very least quick follow-up of change, otherwise you are dead.

- Constant reorganizations and restructurings do not hide deeper issues, they only distract from focusing on the reader. Kodak is now reorganizing its units. Sears did the same thing recently. How many times do newspapers need to separate digital editions into independent units or return them to a single editorial office, wasting time and money, instead of really understanding the meaning and advantages of the actions taken?

- Selling assets is a temporary patch. Kodak is diligently trying to sell the remnants of its intellectual property, although much of it is still a big question. Selling will bring some money, but will not solve the root problems and undermine the basis for innovation. Newspapers have little intellectual property (perhaps they have more intellectual capital), so they sell their real assets - buildings, land. They gain time, but not as much as we would like.

- And finally, perhaps the most striking parallel: the old companies are still stuck with brains in the manufactory.Kodak makes film and goods. Sears sells goods. Newspapers print products and a significantly larger number of "print" sites. The new world is not built on goods, but on service. Photos from the iPhone are taken just to capture the moment, for family albums, but more often just as a keepsake, for yourself or a group of people, about a place or event. They are like an extension of our brain, to which we then return. Target stores (“Expect more, pay less”) focus on the price, but do not forget about the attitude and service. News is a story about how to get what is interesting to me now, and not a product. Of course, changing such a manufacturing approach is very difficult. He brought income, which drooled for decades. Nevertheless, it is so outdated, and those who adhere to it will go to the bottom with it.

Another fresh victim of the old approach is the Best Buy chain of stores. She built large, expensive megastores, alive after eating CompUSA and Circuit City. Now Amazon and hundreds of other sites have made it so that buying and delivering a 62-inch TV to your home is no more difficult than buying a sweater. Looking at the financial results of the holiday sales, Best Buy CEO Brian Dunn (as well as the directors of Kodak, Sears and the newspapers before him), saliva said : “This wrong point of view [that the purchase of electronics went online] is especially worrying for me because it blatantly and thoughtlessly ignores the evidence to the contrary. ” His annoyance is understandable, but history increasingly throws up examples of those defeated who could not adapt quickly enough.

Kodak photo takenKevin Stanfield and used under license from Creative Commons.