Breaking down the fundamentals of C #: allocating memory for a reference type on the stack

This article will show the basics of internal device types, as well as an example in which the memory for the reference type will be allocated completely on the stack (this is because I am a full-stack programmer).

This article does not contain material that should be used in real projects. It is simply an extension of the boundaries in which a programming language is perceived.

Before proceeding with the story, I strongly recommend that you read the first post about StructLayout , because there is an example that will be used in this article (However, as always).

Starting to write code for this article, I wanted to do something interesting using assembly language. I wanted to somehow break the standard execution model and get a really unusual result. And remembering the frequency with which people say that the reference type differs from the significant one in that the first is located on the heap and the second on the stack, I decided to use an assembler to show that the reference type can live on the stack. However, I began to run into all sorts of problems, for example, returning the desired address and its presentation as a managed link (I am still working on it). So I started to cheat and do something that does not work in assembly language, in C #. And in the end, the assembler is not left at all.

Also, the recommendation is to read - if you are familiar with the device of reference types, I recommend skipping the theory about them (only the basics will be given, nothing interesting).

I would like to remind that the division of memory into a stack and a heap occurs at the .NET level, and this division is purely logical; there is physically no difference between the memory areas under the heap and the stack. The difference in productivity is already provided specifically for work with these areas.

How, then, allocate memory on the stack? To begin with, let's understand how this mysterious reference type is arranged and what is in it, which is not in the meaningful.

So, consider the simplest example with the class Employee.

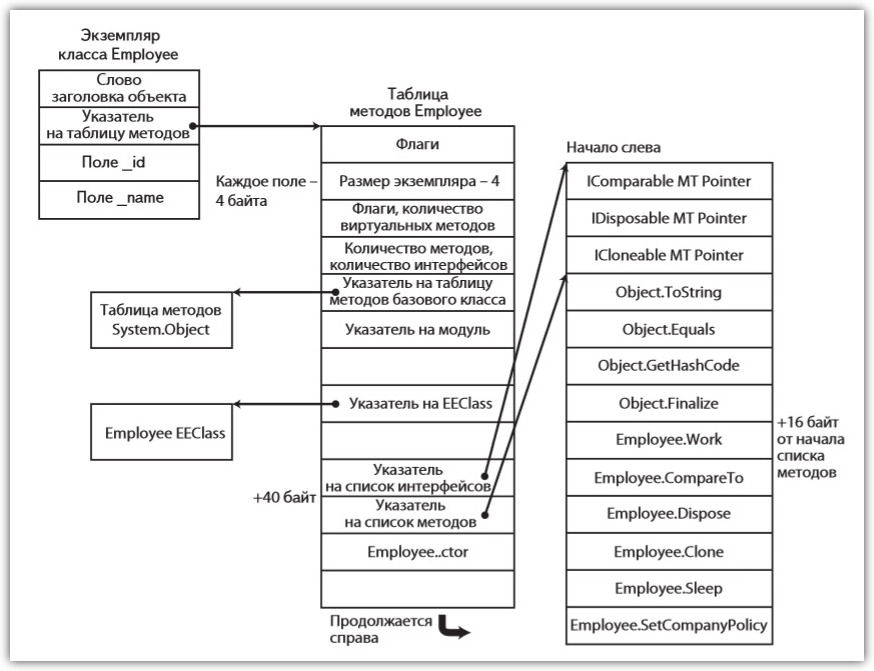

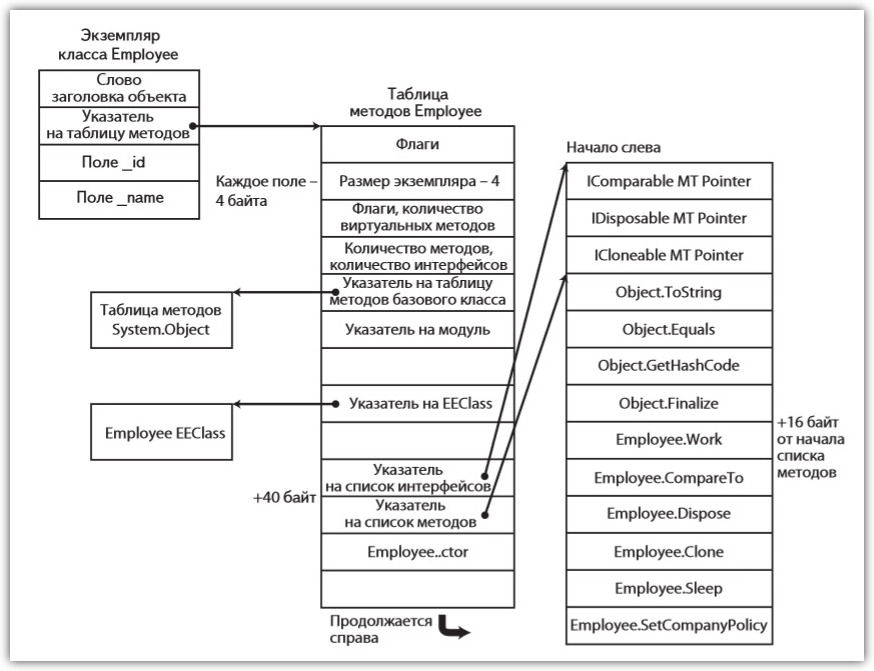

And take a look at how it is presented in memory.

UPD: This class is considered on the example of a 32-bit system.

Thus, in addition to the memory for the fields, we have two more hidden fields - the index of the synchronization block (the word of the object title in the picture) and the address of the method table.

The first field, it is the synchronization block index, does not really interest us. When placing the type I decided to lower it. I did this for two reasons:

But since we have already started talking, I think it is right to say a few words about this field. It is used for different purposes (hash code, synchronization). Rather, the field itself is simply an index of one of the synchronization blocks associated with the object. The blocks themselves are located in the table of synchronization blocks (a la global array). Creating such a block is a rather large operation, so it is not created if it is not needed. Moreover, when using thin locks, the identifier of the thread that received the lock (instead of the index) will be written there.

The second field is much more important for us. Thanks to the table of type methods, such a powerful tool as polymorphism is possible (which, by the way, structures, stack kings, do not possess). Suppose the Employee class additionally implements three interfaces: IComparable, IDisposable, and ICloneable.

Then the table of methods will look something like this. The

picture is very cool, in principle everything is painted and understandable there. If on the fingers and shortly, the call to the virtual method does not occur directly by address, but by the offset in the method table. In the hierarchy, the same virtual methods will be located at the same offset in the method table. That is, on the base class we call the method by offset, not knowing which type of method table will be used, but knowing that this offset will be the most relevant method for the type of runtime.

It is also worth remembering that the object reference points to the method table.

Let's start with classes that will help us in our goal. Using StructLayout (I really tried without it, but it didn't work out), I wrote the simplest mapper pointers to managed types and back. Getting a pointer from a managed link is pretty easy, but the inverse transformation caused me difficulties and, without thinking twice, I applied my favorite attribute. To keep the code in one key, made in 2 directions in one way.

First, let's write a method that takes a pointer to some memory (not necessarily on the stack, by the way) and configures the type.

For ease of finding the address of the method table, I create a type on the heap. I am sure that the table of methods can be found in other ways, but I did not set myself the goal of optimizing this code, it was more interesting for me to make it understandable. Further, using the previously described converters, we obtain a pointer to the type created.

This pointer points exactly to the method table. Therefore, it is sufficient to simply obtain the contents from the memory to which it points. This will be the address of the method table.

And since the pointer passed to us is a kind of object reference, we must also write the address of the method table exactly where it points.

Actually, that's all. Suddenly, right? Now our type is ready. Pinocchio, who allocated memory to us, will take care of initializing the fields himself.

It remains only to use GrandCaster to convert the pointer into a managed link.

Now we have a link on the stack, which points to the same stack, where according to all the laws of reference types (well, almost) lies an object constructed from black earth and sticks. Polymorphism is available.

It should be understood that if you pass this link outside the method, then after returning from it, we will get something unclear. About the calls of virtual methods and speech can not be, we fly on the exception. Normal methods are called directly, the code will just have addresses for real methods, so they will work. And in place of the fields will be ... and no one knows what will be there.

Since it is impossible to use a separate method for initialization on the stack (since the stack frame will be overwritten after returning from the method), the method that wants to apply the type on the stack must allocate memory. Strictly speaking, there is not one way to do it. But the most suitable for us is stackalloc. Just the perfect keyword for our purposes. Unfortunately, it was this that caused the uncontrollability in the code. Before that, there was an idea to use Span for these purposes and to do without unsafe code. There is nothing wrong with unsafe code, but like everywhere, it is not a silver bullet and has its own areas of application.

Then, after receiving a pointer to the memory on the current stack, we pass this pointer to the method that makes up the type in parts. That's all who listened - well done.

You should not use it in real projects, the method allocating memory on the stack uses new T (), which in turn uses reflection to create a type on the heap! So this method will be slower than the usual creation of the type of times well, well in 40-50.

Here you can see the whole project.

Source: in the theoretical guide, examples from the book Sasha Goldstein - Pro .NET Performace were used

Disclaimer

This article does not contain material that should be used in real projects. It is simply an extension of the boundaries in which a programming language is perceived.

Before proceeding with the story, I strongly recommend that you read the first post about StructLayout , because there is an example that will be used in this article (However, as always).

Prehistory

Starting to write code for this article, I wanted to do something interesting using assembly language. I wanted to somehow break the standard execution model and get a really unusual result. And remembering the frequency with which people say that the reference type differs from the significant one in that the first is located on the heap and the second on the stack, I decided to use an assembler to show that the reference type can live on the stack. However, I began to run into all sorts of problems, for example, returning the desired address and its presentation as a managed link (I am still working on it). So I started to cheat and do something that does not work in assembly language, in C #. And in the end, the assembler is not left at all.

Also, the recommendation is to read - if you are familiar with the device of reference types, I recommend skipping the theory about them (only the basics will be given, nothing interesting).

A little about the internal device types

I would like to remind that the division of memory into a stack and a heap occurs at the .NET level, and this division is purely logical; there is physically no difference between the memory areas under the heap and the stack. The difference in productivity is already provided specifically for work with these areas.

How, then, allocate memory on the stack? To begin with, let's understand how this mysterious reference type is arranged and what is in it, which is not in the meaningful.

So, consider the simplest example with the class Employee.

Employee code

publicclassEmployee

{

privateint _id;

privatestring _name;

publicvirtualvoidWork()

{

Console.WriteLine(“Zzzz...”);

}

publicvoidTakeVacation(int days)

{

Console.WriteLine(“Zzzz...”);

}

publicstaticvoidSetCompanyPolicy(CompanyPolicy policy)

{

Console.WriteLine("Zzzz...");

}

}

And take a look at how it is presented in memory.

UPD: This class is considered on the example of a 32-bit system.

Thus, in addition to the memory for the fields, we have two more hidden fields - the index of the synchronization block (the word of the object title in the picture) and the address of the method table.

The first field, it is the synchronization block index, does not really interest us. When placing the type I decided to lower it. I did this for two reasons:

- I am very lazy (I did not say that the reasons will be reasonable)

- For the basic operation of an object, this field is not necessary.

But since we have already started talking, I think it is right to say a few words about this field. It is used for different purposes (hash code, synchronization). Rather, the field itself is simply an index of one of the synchronization blocks associated with the object. The blocks themselves are located in the table of synchronization blocks (a la global array). Creating such a block is a rather large operation, so it is not created if it is not needed. Moreover, when using thin locks, the identifier of the thread that received the lock (instead of the index) will be written there.

The second field is much more important for us. Thanks to the table of type methods, such a powerful tool as polymorphism is possible (which, by the way, structures, stack kings, do not possess). Suppose the Employee class additionally implements three interfaces: IComparable, IDisposable, and ICloneable.

Then the table of methods will look something like this. The

picture is very cool, in principle everything is painted and understandable there. If on the fingers and shortly, the call to the virtual method does not occur directly by address, but by the offset in the method table. In the hierarchy, the same virtual methods will be located at the same offset in the method table. That is, on the base class we call the method by offset, not knowing which type of method table will be used, but knowing that this offset will be the most relevant method for the type of runtime.

It is also worth remembering that the object reference points to the method table.

Long-awaited example

Let's start with classes that will help us in our goal. Using StructLayout (I really tried without it, but it didn't work out), I wrote the simplest mapper pointers to managed types and back. Getting a pointer from a managed link is pretty easy, but the inverse transformation caused me difficulties and, without thinking twice, I applied my favorite attribute. To keep the code in one key, made in 2 directions in one way.

Code here

// Предоставляет нужные нам сигнатурыpublicclassPointerCasterFacade

{

publicvirtualunsafe T GetManagedReferenceByPointer<T>(int* pointer) => default(T);

publicvirtualunsafeint* GetPointerByManagedReference<T>(T managedReference) => (int*)0;

}

// Предоставляет нужную нам логикуpublicclassPointerCasterUnderground

{

publicvirtual T GetManagedReferenceByPointer<T>(T reference) => reference;

publicvirtualunsafeint* GetPointerByManagedReference<T>(int* pointer) => pointer;

}

[StructLayout(LayoutKind.Explicit)]

publicclassPointerCaster

{

publicPointerCaster()

{

pointerCaster= new PointerCasterUnderground();

}

[FieldOffset(0)]

private PointerCasterUnderground pointerCaster;

[FieldOffset(0)]

public PointerCasterFacade Caster;

}

First, let's write a method that takes a pointer to some memory (not necessarily on the stack, by the way) and configures the type.

For ease of finding the address of the method table, I create a type on the heap. I am sure that the table of methods can be found in other ways, but I did not set myself the goal of optimizing this code, it was more interesting for me to make it understandable. Further, using the previously described converters, we obtain a pointer to the type created.

This pointer points exactly to the method table. Therefore, it is sufficient to simply obtain the contents from the memory to which it points. This will be the address of the method table.

And since the pointer passed to us is a kind of object reference, we must also write the address of the method table exactly where it points.

Actually, that's all. Suddenly, right? Now our type is ready. Pinocchio, who allocated memory to us, will take care of initializing the fields himself.

It remains only to use GrandCaster to convert the pointer into a managed link.

publicclassStackInitializer

{

publicstaticunsafe T InitializeOnStack<T>(int* pointer) where T : new()

{

T r = new T();

var caster = new PointerCaster().Caster;

int* ptr = caster.GetPointerByManagedReference(r);

pointer[0] = ptr[0];

T reference = caster.GetManagedReferenceByPointer<T>(pointer);

return reference;

}

}

Now we have a link on the stack, which points to the same stack, where according to all the laws of reference types (well, almost) lies an object constructed from black earth and sticks. Polymorphism is available.

It should be understood that if you pass this link outside the method, then after returning from it, we will get something unclear. About the calls of virtual methods and speech can not be, we fly on the exception. Normal methods are called directly, the code will just have addresses for real methods, so they will work. And in place of the fields will be ... and no one knows what will be there.

Since it is impossible to use a separate method for initialization on the stack (since the stack frame will be overwritten after returning from the method), the method that wants to apply the type on the stack must allocate memory. Strictly speaking, there is not one way to do it. But the most suitable for us is stackalloc. Just the perfect keyword for our purposes. Unfortunately, it was this that caused the uncontrollability in the code. Before that, there was an idea to use Span for these purposes and to do without unsafe code. There is nothing wrong with unsafe code, but like everywhere, it is not a silver bullet and has its own areas of application.

Then, after receiving a pointer to the memory on the current stack, we pass this pointer to the method that makes up the type in parts. That's all who listened - well done.

unsafeclassProgram

{

publicstaticvoidMain()

{

int* pointer = stackallocint[2];

var a = StackInitializer.InitializeOnStack<StackReferenceType>(pointer);

a.StubMethod();

Console.WriteLine(a.Field);

Console.WriteLine(a);

Console.Read();

}

}

You should not use it in real projects, the method allocating memory on the stack uses new T (), which in turn uses reflection to create a type on the heap! So this method will be slower than the usual creation of the type of times well, well in 40-50.

Here you can see the whole project.

Source: in the theoretical guide, examples from the book Sasha Goldstein - Pro .NET Performace were used