SVG Ups and Downs

- Transfer

SVG - a scalable vector graphics markup language included in a subset of XML was created in 1999, but only in 2011 was it included in the W3C recommendations . Surprisingly, for eleven years (from 2000 to 2011) SVG has not undergone significant changes. Nevertheless, he still managed to gain the trust and widespread recognition of the developers.

SVG - a scalable vector graphics markup language included in a subset of XML was created in 1999, but only in 2011 was it included in the W3C recommendations . Surprisingly, for eleven years (from 2000 to 2011) SVG has not undergone significant changes. Nevertheless, he still managed to gain the trust and widespread recognition of the developers. One of these developers, who observed the evolution of SVG from its inception to the present day, conducted an excursion into the history of the language. Only now, after many years, he managed to understand the reasons for the success and failure of SVG. The author collected all his observations and conclusions in the chronicle “Rises and Falls of SVG”. The post was prepared specifically for the PayOnline corporate block, a company that organizes payments on sites and in mobile applications. Further directly the translation.

Sometime in 1998, my ex-colleague, who was working at Adobe at that time, looked into my office to tell me about a completely new technology. She knew that I would be interested. It was then about PGML or "Precision Graphics Markup Language", which was nothing more than a variation of Adobe on XML for vector graphics. John Warnock, one of the founders of Adobe, then said the following about him:

“The introduction of PGML addresses the growing demand for accurate specifications that allow members of the online community to quickly and reliably manage and interact with graphics on the Web.”I went into the study of PGML and since then I began to closely monitor the XML-standards of vector graphics. PGML from Adobe, VML from Microsoft, as well as other similar projects (Web Schematics, Hyper Graphics Markup Language, WebCGM, and DrawML) soon merged into a tangible W3C standard called Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG). It was assumed that the main purpose of the new format will be the display of interactive vector graphics in web browsers. In those days of Netscape Navigator 4.7 and Internet Explorer 5, this task was only possible with Macromedia Flash.

In 2000, the situation cleared up.

What was so cool about SVG? It was practically “PostScript for web development”, so Adobe’s decision to sponsor and support it in the early stages of development was quite understandable: like Postscript, SVG made it possible to describe images using vectors, almost without resorting to other solutions. This approach was much more effective than using raster graphics, and also allowed to achieve much more natural scaling.

However, there was one more thing that made SVG even cooler: unlike PostScript, SVG was written declaratively inside as part of the standard markup of the XML meta-language. That is, mere mortals could safely open a text file, write something like

... then save this file, upload it to the browser and look at the result. You could go further and write a script according to the rules of the Document Object Model (DOM), which would animate the drawn image or change the parameters specified in the XML code. In contrast to the then available alternative in the form of Macromedia Flash, this method was more understandable for the user. In addition, the textual nature of the markup made it easy to search by code. Initially, a plug-in was required to display SVG graphics, but ultimately the standard provided for built-in support from the browser.

For me, the arguments in favor of this technology were obvious: its application would lead to progress in the field of web technologies, and it itself should have received the widest distribution. Soon after, I found SVG Developers group on Yahoo, where the same developers like me “flew into the light”.

1999 smoothly flowed into 2000, and then I got the impression that the widespread adoption of SVG was just around the corner. I was sure that this would happen in 2001 or, as a last resort, in 2002. The advent of SVG seemed completely natural. In addition, experience has shown that in the 1990s, standards usually required distribution for about two years. However, the “sudden success” of SVG was destined to happen much later than I expected. The year 2002 managed not only to begin, but also to end, and only Macromedia Flash managed to spread during this time.

2003: stagnation time in the development of web standards

We and other members of the SVG community made every possible effort to develop the optimal specification for the standard, and also tried to support reasonable and relevant examples of its implementation in software of the time. Of course, our main goal was the built-in support for the standard in browsers, but we also needed support from the developers of desktop graphics applications. At first, good news came from both fronts.

Best times

In 2003, Adobe offered the SVG Viewer to display SVG in browsers, and Illustrator was a tool for personal creativity. At the same time, Mozilla began work on embedding standard support in its browser. Needless to say, even Microsoft Visio supported SVG. There were many good examples that demonstrated the capabilities of SVG. Among them were not only cartographic applications or samples of data visualization, but even vector analogues of Flash sites.

Several books have also been written about SVG. The introduction to one of them, SVG Unleashed by Chris Liley, ended with the words “welcome to the future”.

Worst times

Despite all this, I was increasingly feeling that the future would never come: Adobe SVG Viewer, the only tool for displaying SVG graphics in the browser at that time, was not widely used. Microsoft strongly ignored SVG in Internet Explorer 6. Without the support of the most popular web browser, the development of the standard stalled and became useless as a standard format for web publishing. It was perfect for closed systems, its aesthetics attracted geeks, but in general, SVG fell out of the mainstream and was unknown to most Internet users. The only widespread vector graphics technology was Macromedia Flash.

Two major constraints

More than ten years have passed since then, and now it’s easy for me to determine what difficulties SVG faced then and understand why it took so long to conquer the world. At that time, I completely did not understand what was the matter and could not predict how events would develop. However, it is always easier to think retroactively ...

Browser wars or “who needs these standards at all”?

I remember lovingly Mozilla of those times. They had serious intentions to implement SVG and they did everything they could to do this. This is not to say that work progressed rapidly, but progress was steady. As a result, the built-in, not requiring the installation of third-party plug-ins, SVG support first appeared and was successfully tested precisely in their builds.

In 2002, Microsoft contacted me and offered to hire our entire company (however, there were only two of us). My first reaction was “Why?”, But it soon became clear to me that they knew everything about our work with SVG. Regardless of whether Microsoft planned to support SVG or not, it was obvious that they were up to something. In the end, it turned out that even despite the attention with which the company followed SVG, it was not at all going to apply the standard in its purest form. Instead, Microsoft tried to unceremoniously copy SVG. This attempt was embodied in the form of the XAML markup language, designed to display vector and animated content using Silverlight technology, which has never gained popularity. XAML was strikingly similar to SVG.

Adobe, meanwhile, continued to support SVG Viewer, as well as authoring tools that worked with SVG, such as FrameMaker, Illustrator, InDesign, and GoLive. Nevertheless, they could not influence Microsoft to change its course. The positions of Internet Explorer were extremely strong back then, and whenever it came to creating a lot of vector content, most designers and developers continued to choose Macromedia Flash. Despite the superiority of SVG in technical terms, the decisive factor in this confrontation was the alignment of forces in the browser market. In light of Microsoft's superiority, the support that Adobe provided to SVG seemed more like an experiment than a full-fledged effort.

“Standards are for Losers”

- Cynics

In a situation where Internet Explorer without any support for SVG was reaping the benefits of its enormous popularity, and Flash was the only browser plug-in that was in real demand among users (due to the fact that it appeared on the market at the right time), neither Microsoft nor Macromedia were interested in support for open technology that can level the capabilities of players. Those companies that supported SVG were outsiders. Among them were both engineers who saw in it a more advanced and, therefore, more popular technology in the future, and businesses for which the use of SVG was a way to step on the heels of large monopolists who dominate the market thanks to their closed technologies.

Standards wars or “all your text is ours now”

However, even if the monopolists, bravely rejecting the interests of their shareholders, fell under the banner of SVG, the latter would still meet resistance, already from other technologies. The fact is that SVG existed at the intersection of several other standards, two of which - HTML and CSS - appeared much earlier. SVG was a newer set of specifications. By the early 2000s, the W3C had a far from perfect reputation. The organization managed to celebrate the creation of several useless (Xlink) and frankly unsuccessful (XML Schema) standards. An illustrative example of W3C failures is XHTML. The seemingly simplest task of putting SVG in the context of intersecting HTML and CSS was complicated by the fact that both of these technologies were in a state of constant change, not necessarily moving in the right direction.

Take, for example, word processing. SVG 1.0 lacked such a demanded feature as text that adapts to the shape of the container with the correct word wrap. The SVG working group, taking up the task, immediately realized that this was not in its area of responsibility, since the CSS working group had already managed to seriously work on the textual component before them ... Political issues and a variety of technical approaches prevented determining what specific role in everything This was supposed to play SVG.

Take, for example, word processing. SVG 1.0 lacked such a demanded feature as text that adapts to the shape of the container with the correct word wrap. The SVG working group, taking up the task, immediately realized that this was not in its area of responsibility, since the CSS working group had already managed to seriously work on the textual component before them ... Political issues and a variety of technical approaches prevented determining what specific role in everything This was supposed to play SVG.In 2004, the Compound Document Format working group was formed. Her task was to develop a document format that would combine several different formats, such as XHTML and SVG. Of course, such a development required built-in browser support, since writing SVG code through a plug-in would not allow for a good combination of SVG and HTML syntax.

The beginning of work on CDF coincided in time with the birth of HTML5, the concept of which openly contradicted the movement of HTML towards XML, that is, its transformation into XHTML. The "fifth version" took a different approach to combining technology similar in spirit. The consequence of this approach was the even greater intersection of SVG and Canvas, a set of techniques for displaying graphics presented in HTML5. In the end, work on CDF was discontinued, but it paid off: a significant part of the development contributed to the development of HTML5.

Developers using proprietary technologies such as Flash do not face the challenge of choosing technologies. Open standards, by contrast, require an understanding of the mechanics of their interaction with each other. Over time, working with a whole range of such technologies can be difficult for developers and designers. In cases where the same problem can be solved in three different ways, determining the optimal one is usually not easy. Add to this the fact that the variety of display technologies makes developers hope for the good quality of their implementations in each browser.

2005: Adobe abandons SVG

Adobe has endured for many years all the vicissitudes of supporting the “loser standard”. Obviously, the company is tired of fighting for justice and suffering defeats in the fight against monopolists. In 2005, she announced the acquisition of Macromedia, its largest and probably only competitor. This event had negative consequences for the SVG community: already in 2006, SVGViewer was deprecated, and the tools that allowed working with SVG were removed from other applications.

Adobe provided significant support to Flash and spared no effort and effort to refine it. This allowed the technology to conquer more than 90% of the market, becoming an almost universal graphic platform for personal computers. As for all other devices, they were still unable to fully display web pages or graphics. Thanks to Flash, Adobe’s plans to capture the market gradually came to fruition.

Instead of taking SVG into service as an alternative, Microsoft released after a while its belated version - Silverlight. The seventh and eighth generations of Internet Explorer continued to ignore SVG.

And while Adobe and Microsoft were developing proprietary alternatives to SVG, the working group was still developing the standard, while other “losers” like Mozilla continued to move the technology forward. The SVG standard “prettier” with the advent of version 1.2, which contained a few modest “features”. At the same time, work was underway on version 1.1, fixing bugs hastily created version 1.0. Both options have been developed over several years.

In December 2008, SVG 1.2 Tiny became a W3C recommendation, while SVG 1.1, which contained bug fixes and clarifications for version 1.0, achieved the same status in 2011.

SVG has received solid support from Firefox and Webkit. Thanks to Webkit, SVG made money in Chrome and Safari. Internet Explorer is now completely isolated. He gradually lost his popularity, which went to Chrome and Firefox. At the same time, Silverlight's attempt to get to its feet failed.

Due to the rapid spread of Flash advertising and the growth of the number of "rich Internet applications", Adobe Flash has maintained a strong position in the desktop browser segment. However, in the segment of mobile devices, which, with the release of the iPhone in 2007, have grown significantly in terms of browser functionality, Flash has fought an uneven battle. SVG support appeared on the iPhone in 2008. Flash support was out of the question.

2010: The humble SVG finally inherited the throne

Later, in 2010, Steve Jobs published his Flash Thoughts . According to Jobs, the only available alternative to Flash was a combination of technologies, of which SVG was an integral part.

Adobe’s ambitions for Flash, AIR, and the Open Street Project posed a significant threat to Apple’s closed ecosystem. Although Jobs’s remarks about the unwanted use of plug-ins in browsers and the terrible Flash performance on mobile devices were fully substantiated, the threat that Flash / AIR posed to Apple was primarily economic in nature, and it was she who forced Jobs to regain his love for standards. Thanks to the iPhone and iPad, Apple could destroy Flash and this confrontation came in handy for SVG, which had already become part of HTML5. Thanks to this, SVG could finally get the attention and support that it has deserved for a long time.

Microsoft and Apple began to fully support and implement SVG as soon as it became “politically expedient”. In 2011, Microsoft even held the SVG Open conference , which in the light of the events of previous years seemed somehow unbelievable.

I can assure you that the 2011 version of SVG has not undergone major changes compared to the 2000 version. Demonstrated during the presentation of Internet Explorer 9 examples of displaying SVG, such as the magnificent work in the field of cartography from Cargo.net, were nothing more than “old samples” developed back in the early 2000s. In general, the SVG applications written in 2001 worked great on the iPad when it first appeared. Microsoft implemented SVG with one annoying feature: it refused to reproduce support for SMIL, a specification that was popular among early SVG developers for animating graphics. Even today, when Google plans to use SMIL in its products, Microsoft seems to be winning the battle to supplant it.

Despite all this, the overall level of built-in support is impressive today. Basic SVG functionality is available on all web systems today.

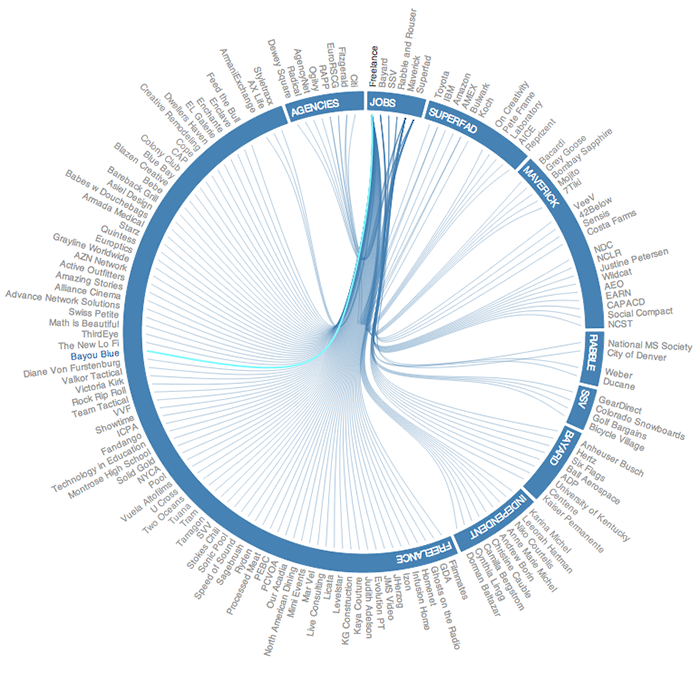

Libraries and frameworks for visualizing and working with SVG, such as d3.js, are growing and developing. Some of them have reached a very high level. SVG graphics are now available in more than 2 million devices worldwide, and Adobe has returned standard support to its graphics applications. Recently, the company has even made significant progress in this direction: the CC2015.2 release of December 1 offers excellent opportunities for exporting SVG graphics from Illustrator and importing it into Photoshop. Compared to the first export options, this is a giant leap forward.

Now that SVG is widely distributed and fully supported by browsers, and development tools are developing in the right direction, SVG has become tightly coupled and compatible with all the technologies used in HTML5: Javascript, HTML, CSS, Canvas, and WebGL. The standard is moving forward again , this time in harmony with other technologies. Summing up the general results, we can say that SVG managed to achieve the goals set at the very beginning of its existence. It just took more time than some of us expected.

The good always comes to those who know how to wait.

The material for publication was prepared by PayOnline, an international system for accepting electronic payments on the site and in mobile applications. If you need to arrange payment acceptance, feel free tocontact . Also subscribe to our corporate blog , there are many more interesting posts ahead.