The gravitational field on the surface of bodies of irregular shape on the example of comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko

From the law of universal gravitation it is known that on the surface of bodies of a spherical shape, the acceleration of gravity is constant in absolute value and directed toward the center of the ball. For bodies of irregular shape, this rule is obviously not satisfied. In this article, I will show a method for calculating and visualizing gravitational acceleration for such bodies. We will calculate in JavaScript, visualize in WebGL using the three.js library .

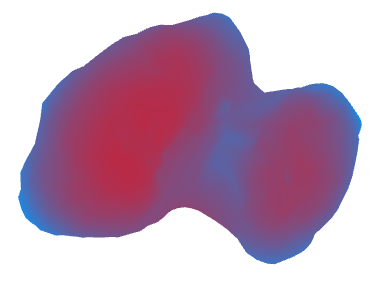

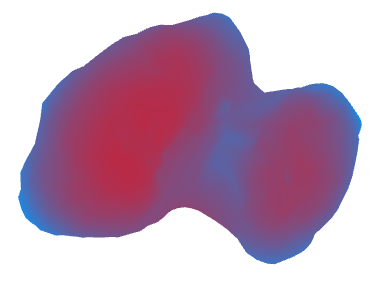

As a result, we get the following (areas with a large acceleration of gravity are marked in red, blue with a small acceleration):

The following formula is used to calculate the gravitational potential of the planets :

But, unfortunately, for small r this series converges slowly, and for very small r it diverges altogether. Therefore, this formula is not suitable for calculating the gravitational potential on the surface of celestial bodies. In the general case, it is necessary to carry out integration over the entire volume of the body.

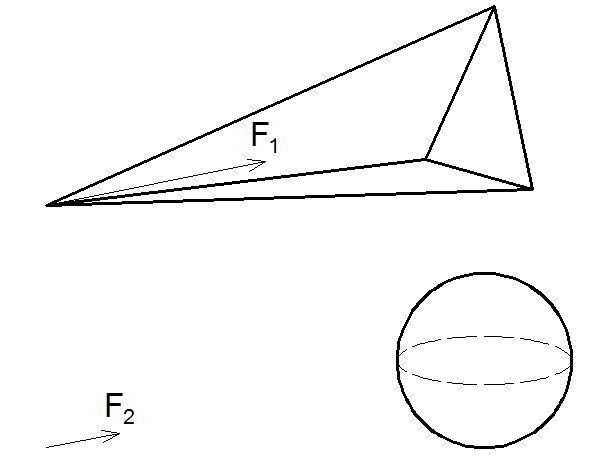

A three-dimensional body can be represented as sets of triangular faces, with the given coordinates of the vertices. Further, we will assume that the density of the body is constant (for a comet this roughly corresponds to the truth). The gravitational potential at a given point will be equal to the sum of the potentials of all tetrahedra, with a base at these faces and with a vertex at a given point (we are not looking for the gravitational potential, but the gravitational acceleration, which is the gradient of the potential, but the reasoning remains the same).

To begin with, we need to find the acceleration that the mass of the tetrahedron produces at the point at its top. To do this, integrate over the entire volume of the tetrahedron. Unfortunately, this integral is not taken in elementary functions, so you have to go to the trick.

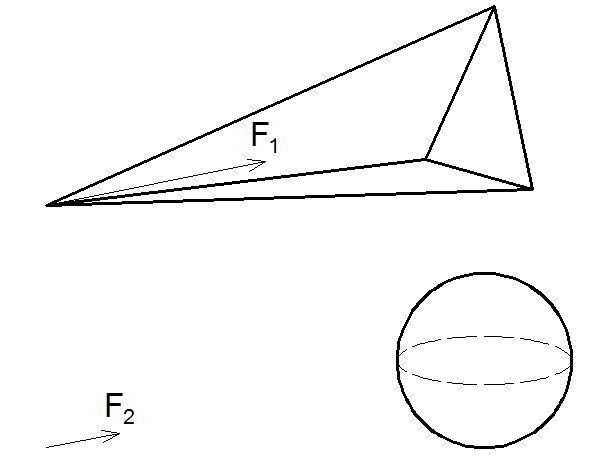

The force acting on the point at the top of the tetrahedron is approximately three times greater than the force caused by the gravity of the ball placed in the middle of the base of the tetrahedron (the mass of the ball is equal to the mass of the tetrahedron). That is, F 1 ≈3 * F 2 . This equality is better satisfied with a small angle of the tetrahedron solution. To estimate the deviation of equality from strict, I generated several thousand random tetrahedrons and calculated this value for them.

The graph on the abscissa shows the ratio of the perimeter of the triangular base to the distance from the top to the center of the base. The y-axis is the magnitude of the error. As can be seen, the magnitude of the error can be represented by a quadratic function. With rare exceptions, all points are below the parabola (exceptions, we will not be particularly spoiled by the weather).

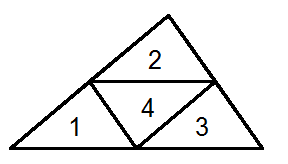

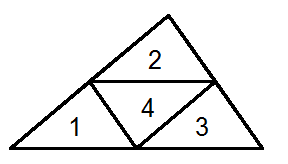

The value of gravitational acceleration will be calculated with a given relative error. If the calculation error exceeds this error, then we divide our tetrahedron into four parts at the base and calculate the acceleration for these parts separately, then add up.

We find the acceleration to within a certain constant, for a given body, coefficient, depending on the mass (or density) of the body, the gravitational constant and some other parameters. We will take this coefficient into account later.

The acceleration from a three-dimensional body is calculated by summing over all tetrahedra formed by the faces of the body and the given point (which I wrote about earlier).

We calculate the gravitational and centrifugal accelerations on the comet (the rotation of the comet causes an acceleration of about 25% of the gravitational one, therefore it cannot be neglected). I set the relative error to 0.01. It would seem a lot, but in fact when calculating the error, it turns out three times less and during visualization the difference is absolutely not noticeable (since the minimum difference in the color of the pixels is 1 / 256≈0.004). And if you set the error less, then the calculation time increases.

With an error of 0.01, the calculation takes 1-2 seconds, so we execute it through setInterval, in order to avoid freezing the browser.

Now it’s worth talking about the format of working with a 3D body. Everything is simple here. This is an object consisting of three arrays: vertices, normals, and triangular faces.

An array of vertices stores vertex coordinate vector objects. An array of normals is the normal vectors of the vertices. Array of faces - arrays of three numbers that store vertex numbers.

I downloaded the model of Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet from the ESA website and simplified it in 3Ds Max. There were several tens of thousands of vertices and faces in the original model, but this is too much for our task, because the computational complexity of the algorithm depends on the product of the number of vertices and the number of faces. The model is saved in obj format .

The three.js library has an OBJLoader function for loading this format, but only the vertex information remains when loading, and the face information is lost, which is not suitable for our task. Therefore, I modified it somewhat.

So, we loaded the object from the file, then calculated the acceleration vector at each of its vertices, now we need to visualize it. To do this, create a scene, configure the camera and light, add and colorize our model.

The scene is easy to create.

There are no problems with the camera either.

To create the camera, we used the THREE.PerspectiveCamera function (fov, aspect, near, far), where:

fov is the height of the camera’s field of view in degrees;

aspect - the ratio of the horizontal angle of view of the camera to the vertical;

near - the distance to the near plan (what is closer will not be rendered);

far - the distance to the background.

Put the light on.

Create a visualizer.

For working with models in three.js it is convenient to use the BufferGeometry class.

We set the material.

We load the coordinates of the vertices.

Calculate the color of the vertices.

We also need to display the directions of acceleration of gravity at each vertex.

With visualization done. We look what happened.

Demo 1 .

As you can see, the acceleration of gravity on a comet is from 40 to 80 thousand times less than on Earth. The maximum deviation of the acceleration vector from the normal is about 60-70 degrees. Small and large stones in these areas probably do not linger and slowly roll into areas where the angle is not so large.

You can play with bodies of a different shape. Demo 2 .

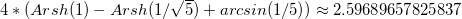

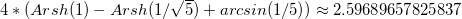

We see that for a cube the maximum acceleration (in the center of the face) is 1.002 accelerations for a ball of the same mass, but in fact this value is slightly less than unity (what we considered with a relative error of 0.01 played a role). For a cube, unlike a tetrahedron, there are exact formulas for calculating accelerations and the exact value for the center of the face is (for a cube with a side equal to 1):

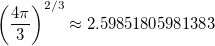

For a ball of the same volume:

Their ratio is 0.999376 and only slightly falls short of unity.

In conclusion, the question. Are there bodies in which at least at one point the ratio of the absolute value of gravitational acceleration to acceleration on the surface of a ball of the same mass and volume is greater than unity? If so, for which body is this ratio maximum? How many times is this ratio greater than unity, at times or a fraction of a percent?

As a result, we get the following (areas with a large acceleration of gravity are marked in red, blue with a small acceleration):

GIF

The rotation axis on the GIF is conditional. It does not coincide with the axis of rotation of the comet.

The rotation axis on the GIF is conditional. It does not coincide with the axis of rotation of the comet.

The following formula is used to calculate the gravitational potential of the planets :

But, unfortunately, for small r this series converges slowly, and for very small r it diverges altogether. Therefore, this formula is not suitable for calculating the gravitational potential on the surface of celestial bodies. In the general case, it is necessary to carry out integration over the entire volume of the body.

A three-dimensional body can be represented as sets of triangular faces, with the given coordinates of the vertices. Further, we will assume that the density of the body is constant (for a comet this roughly corresponds to the truth). The gravitational potential at a given point will be equal to the sum of the potentials of all tetrahedra, with a base at these faces and with a vertex at a given point (we are not looking for the gravitational potential, but the gravitational acceleration, which is the gradient of the potential, but the reasoning remains the same).

To begin with, we need to find the acceleration that the mass of the tetrahedron produces at the point at its top. To do this, integrate over the entire volume of the tetrahedron. Unfortunately, this integral is not taken in elementary functions, so you have to go to the trick.

The force acting on the point at the top of the tetrahedron is approximately three times greater than the force caused by the gravity of the ball placed in the middle of the base of the tetrahedron (the mass of the ball is equal to the mass of the tetrahedron). That is, F 1 ≈3 * F 2 . This equality is better satisfied with a small angle of the tetrahedron solution. To estimate the deviation of equality from strict, I generated several thousand random tetrahedrons and calculated this value for them.

The graph on the abscissa shows the ratio of the perimeter of the triangular base to the distance from the top to the center of the base. The y-axis is the magnitude of the error. As can be seen, the magnitude of the error can be represented by a quadratic function. With rare exceptions, all points are below the parabola (exceptions, we will not be particularly spoiled by the weather).

The value of gravitational acceleration will be calculated with a given relative error. If the calculation error exceeds this error, then we divide our tetrahedron into four parts at the base and calculate the acceleration for these parts separately, then add up.

We find the acceleration to within a certain constant, for a given body, coefficient, depending on the mass (or density) of the body, the gravitational constant and some other parameters. We will take this coefficient into account later.

Code time has come

function force_pyramide(p1, p2, p3, rel) {

// начальная точка в (0, 0, 0)

// rel - относительная погрешность

var volume = (1/6) * triple_product(p1, p2, p3); // объём тетраэдра

if (volume == 0)

return new vector3(0, 0, 0);

if (!rel)

rel = 0.01;

var p0 = middleVector(p1, p2, p3); // вектор центра основания

var len = p0.length();

var per = perimeter(p1, p2, p3); // периметр основания

var tan_per = per / len;

var error = 0.015 * sqr(tan_per); // та самая эмпирическая квадратичная функция

if (error > rel) {

var p12 = middleVector(p1, p2);

var p13 = middleVector(p1, p3);

var p23 = middleVector(p2, p3);

return sumVector(

force_pyramide(p1, p12, p13, rel),

force_pyramide(p2, p23, p12, rel),

force_pyramide(p3, p13, p23, rel),

force_pyramide(p12, p23, p13, rel)

);

}

var ratio = 3 * volume * Math.pow(len, -3);

return new vector3(p0.x, p0.y, p0.z).multiplyScalar(ratio);

}

The acceleration from a three-dimensional body is calculated by summing over all tetrahedra formed by the faces of the body and the given point (which I wrote about earlier).

Hidden text

function force_object(p0, obj, rel) {

var result = new vector3(0, 0, 0);

for (var i = 0; i < obj.faces.length; i++) {

p1 = subVectors(obj.vertices[obj.faces[i][0] - 1], p0);

p2 = subVectors(obj.vertices[obj.faces[i][1] - 1], p0);

p3 = subVectors(obj.vertices[obj.faces[i][2] - 1], p0);

var f = force_pyramide(p1, p2, p3, rel);

result = addVectors(result, f);

}

return result;

}

We calculate the gravitational and centrifugal accelerations on the comet (the rotation of the comet causes an acceleration of about 25% of the gravitational one, therefore it cannot be neglected). I set the relative error to 0.01. It would seem a lot, but in fact when calculating the error, it turns out three times less and during visualization the difference is absolutely not noticeable (since the minimum difference in the color of the pixels is 1 / 256≈0.004). And if you set the error less, then the calculation time increases.

With an error of 0.01, the calculation takes 1-2 seconds, so we execute it through setInterval, in order to avoid freezing the browser.

The code

var rel = 0.01;

// относительная погрешность

var scale = 1000;

// модель задана в километрах, переводим в метры

var grav_ratio = 6.672e-11 * 1.0e+13 / (sqr(scale) * volume);

// масса кометы 1е+13 кг

var omega2 = sqr(2 * Math.PI / (12.4 * 3600));

// период вращения кометы 12,4 часов

function computeGrav() {

info.innerHTML = 'Расчёт: ' + (100 * item / object3d.vertices.length).toFixed() + '%';

for (var i = 0; i < 50; i++) {

var p0 = object3d.vertices[item];

grav_force[item] = force_object(p0, object3d, rel).multiplyScalar(grav_ratio);

// гравитационное ускорение

circular_force[item] = new vector3(omega2 * p0.x * scale, omega2 * p0.y * scale, 0);

// центробежное ускорение, ось вращения совпадает с осью z

abs_grav_force[item] = grav_force[item].length();

abs_circular_force[item] = circular_force[item].length();

item++;

if (item >= object3d.vertices.length) {

console.timeEnd('gravity calculate');

clearInterval(timerId);

accelSelect();

init();

animate();

break;

}

}

}

var item = 0;

console.time('gravity calculate');

var timerId = setInterval(computeGrav, 1);

Now it’s worth talking about the format of working with a 3D body. Everything is simple here. This is an object consisting of three arrays: vertices, normals, and triangular faces.

var obj = {

vertices: [],

normals: [],

faces: []

};

An array of vertices stores vertex coordinate vector objects. An array of normals is the normal vectors of the vertices. Array of faces - arrays of three numbers that store vertex numbers.

I downloaded the model of Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet from the ESA website and simplified it in 3Ds Max. There were several tens of thousands of vertices and faces in the original model, but this is too much for our task, because the computational complexity of the algorithm depends on the product of the number of vertices and the number of faces. The model is saved in obj format .

The three.js library has an OBJLoader function for loading this format, but only the vertex information remains when loading, and the face information is lost, which is not suitable for our task. Therefore, I modified it somewhat.

The code

function objLoad(url) {

var result;

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open('GET', url, false);

xhr.onreadystatechange = function(){

if (xhr.readyState != 4) return;

if (xhr.status != 200) {

result = xhr.status + ': ' + xhr.statusText + ': ' + xhr.responseText;

}

else {

result = xhr;

}

}

xhr.send(null);

return result;

}

function objParse(url) {

var txt = objLoad(url).responseText;

var lines = txt.split('\n');

var result;

// v float float float

var vertex_pattern = /v( +[\d|\.|\+|\-|e|E]+)( +[\d|\.|\+|\-|e|E]+)( +[\d|\.|\+|\-|e|E]+)/;

// f vertex vertex vertex ...

var face_pattern1 = /f( +-?\d+)( +-?\d+)( +-?\d+)( +-?\d+)?/;

// f vertex/uv vertex/uv vertex/uv ...

var face_pattern2 = /f( +(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+))( +(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+))( +(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+))( +(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+))?/;

// f vertex/uv/normal vertex/uv/normal vertex/uv/normal ...

var face_pattern3 = /f( +(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+))( +(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+))( +(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+))( +(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+)\/(-?\d+))?/;

// f vertex//normal vertex//normal vertex//normal ...

var face_pattern4 = /f( +(-?\d+)\/\/(-?\d+))( +(-?\d+)\/\/(-?\d+))( +(-?\d+)\/\/(-?\d+))( +(-?\d+)\/\/(-?\d+))?/;

var obj = {

vertices: [],

normals: [],

faces: []

};

for (var i = 0; i < lines.length; i++) {

var line = lines[i].trim();

if ((result = vertex_pattern.exec(line)) !== null) {

obj.vertices.push(new vector3(

parseFloat(result[1]),

parseFloat(result[2]),

parseFloat(result[3])

));

}else if ((result = face_pattern1.exec(line)) !== null) {

obj.faces.push([

parseInt(result[1]),

parseInt(result[2]),

parseInt(result[3])

]);

if (result[4])

obj.faces.push([

parseInt(result[1]),

parseInt(result[3]),

parseInt(result[4])

]);

}else if ((result = face_pattern2.exec(line)) !== null) {

obj.faces.push([

parseInt(result[2]),

parseInt(result[5]),

parseInt(result[8])

]);

if (result[11])

obj.faces.push([

parseInt(result[2]),

parseInt(result[8]),

parseInt(result[11])

]);

}else if ((result = face_pattern3.exec(line)) !== null) {

obj.faces.push([

parseInt(result[2]),

parseInt(result[6]),

parseInt(result[10])

]);

if (result[14])

obj.faces.push([

parseInt(result[2]),

parseInt(result[10]),

parseInt(result[14])

]);

}else if ((result = face_pattern4.exec(line)) !== null) {

obj.faces.push([

parseInt(result[2]),

parseInt(result[5]),

parseInt(result[8])

]);

if (result[11])

obj.faces.push([

parseInt(result[2]),

parseInt(result[8]),

parseInt(result[11])

]);

}

}

obj.normals = computeNormalizeNormals(obj);

return obj;

}

So, we loaded the object from the file, then calculated the acceleration vector at each of its vertices, now we need to visualize it. To do this, create a scene, configure the camera and light, add and colorize our model.

The scene is easy to create.

scene = new THREE.Scene();

There are no problems with the camera either.

var fieldWidth = 500; // размеры холста в пикселях

var fieldHeight = 500;

camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera(50, fieldWidth / fieldHeight, 0.01, 10000);

scene.add(camera);

cameraZ = 3 * boundingSphereRadius;

// boundingSphereRadius - радиус сферы, описанной вокруг нашего тела

camera.position.x = 0;

camera.position.y = 0;

camera.position.z = cameraZ;

camera.lookAt(new THREE.Vector3(0, 0, 0)); // камера смотрит в начало координат

To create the camera, we used the THREE.PerspectiveCamera function (fov, aspect, near, far), where:

fov is the height of the camera’s field of view in degrees;

aspect - the ratio of the horizontal angle of view of the camera to the vertical;

near - the distance to the near plan (what is closer will not be rendered);

far - the distance to the background.

Put the light on.

var ambientLight = new THREE.AmbientLight(0xffffff);

scene.add(ambientLight);

Create a visualizer.

renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer({antialias: true});

renderer.setClearColor(0xffffff); // цвет фона

renderer.setPixelRatio(window.devicePixelRatio);

renderer.setSize(fieldWidth, fieldHeight); // задаём размер холста

container.appendChild(renderer.domElement); // привязываемся к холсту

Together

var container;

var camera, scene, renderer;

var axis;

var mesh;

var boundingSphereRadius, cameraZ;

var lines = [];

var angleGeneral = 0;

function init() {

container = document.getElementById('container');

scene = new THREE.Scene();

var fieldWidth = 500;

var fieldHeight = 500;

camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera(50, fieldWidth / fieldHeight, 0.01, 10000);

scene.add(camera);

var ambientLight = new THREE.AmbientLight(0xffffff);

scene.add(ambientLight);

loadModel();

cameraZ = 3 * boundingSphereRadius;

camera.position.x = 0;

camera.position.y = 0;

camera.position.z = cameraZ;

camera.lookAt(new THREE.Vector3(0, 0, 0));

axis = new THREE.Vector3(0.6, 0.8, 0); //

renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer({antialias: true});

renderer.setClearColor(0xffffff);

renderer.setPixelRatio(window.devicePixelRatio);

renderer.setSize(fieldWidth, fieldHeight);

container.appendChild(renderer.domElement);

}

For working with models in three.js it is convenient to use the BufferGeometry class.

var geometry = new THREE.BufferGeometry();

We set the material.

var material = new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial( {

side: THREE.FrontSide, // отображаться будет только передняя сторона грани

vertexColors: THREE.VertexColors // грани окрашиваются градиентом по цветам их вершин

});

We load the coordinates of the vertices.

var vertices = new Float32Array(9 * object3d.faces.length);

for (var i = 0; i < object3d.faces.length; i++) {

for (var j = 0; j < 3; j++) {

vertices[9*i + 3*j ] = object3d.vertices[object3d.faces[i][j] - 1].x;

vertices[9*i + 3*j + 1] = object3d.vertices[object3d.faces[i][j] - 1].y;

vertices[9*i + 3*j + 2] = object3d.vertices[object3d.faces[i][j] - 1].z;

}

}

geometry.addAttribute('position', new THREE.BufferAttribute(vertices, 3));

Calculate the color of the vertices.

var colors = addColor();

geometry.addAttribute('color', new THREE.BufferAttribute(colors, 3));

function addColor() {

var colorMin = [0.0, 0.6, 1.0]; // цвет точек с минимальным ускорением

var colorMax = [1.0, 0.0, 0.0]; // то же с максимальным

var colors = new Float32Array(9 * object3d.faces.length);

for (var i = 0; i < object3d.faces.length; i++) {

for (var j = 0; j < 3; j++) {

var intensity = (abs_force[object3d.faces[i][j] - 1] - forceMin) / (forceMax - forceMin);

colors[9*i + 3*j ] = colorMin[0] + (colorMax[0] - colorMin[0]) * intensity;

colors[9*i + 3*j + 1] = colorMin[1] + (colorMax[1] - colorMin[1]) * intensity;

colors[9*i + 3*j + 2] = colorMin[2] + (colorMax[2] - colorMin[2]) * intensity;

}

}

return colors;

}

We also need to display the directions of acceleration of gravity at each vertex.

The code

var lines;

function addLines() {

lines = new Array();

for (var i = 0; i < object3d.vertices.length; i++) {

var color;

var ratio;

if (angle_force[i] < 90) {

color = 0x000000; // Вектор ускорения направлен в сторону тела

ratio = -0.2 * boundingSphereRadius / forceMax;

}

else {

color = 0xdddddd; // Вектор ускорения направлен наружу

ratio = 0.2 * boundingSphereRadius / forceMax;

}

var material = new THREE.LineBasicMaterial({

color: color

});

var geometry = new THREE.Geometry();

var point1 = object3d.vertices[i];

var point2 = new THREE.Vector3();

point2.copy(force[i]);

point2.addVectors(point1, point2.multiplyScalar(ratio));

geometry.vertices.push(

new THREE.Vector3(point1.x, point1.y, point1.z),

new THREE.Vector3(point2.x, point2.y, point2.z)

);

var line = new THREE.Line(geometry, material);

rotateAroundWorldAxis(line, axis, angleGeneral);

if (hair.checked)

scene.add(line);

lines.push(line);

}

}

With visualization done. We look what happened.

Demo 1 .

As you can see, the acceleration of gravity on a comet is from 40 to 80 thousand times less than on Earth. The maximum deviation of the acceleration vector from the normal is about 60-70 degrees. Small and large stones in these areas probably do not linger and slowly roll into areas where the angle is not so large.

You can play with bodies of a different shape. Demo 2 .

We see that for a cube the maximum acceleration (in the center of the face) is 1.002 accelerations for a ball of the same mass, but in fact this value is slightly less than unity (what we considered with a relative error of 0.01 played a role). For a cube, unlike a tetrahedron, there are exact formulas for calculating accelerations and the exact value for the center of the face is (for a cube with a side equal to 1):

For a ball of the same volume:

Their ratio is 0.999376 and only slightly falls short of unity.

In conclusion, the question. Are there bodies in which at least at one point the ratio of the absolute value of gravitational acceleration to acceleration on the surface of a ball of the same mass and volume is greater than unity? If so, for which body is this ratio maximum? How many times is this ratio greater than unity, at times or a fraction of a percent?