Accident of the Express-MD1 satellite (July 4, 2013)

Proton with Express-MD1 and Express AM44 on board

Our satellite network has experienced countless minor failures and anomalies in the operation of satellites. Express-2 (failure of correction engines), Express-AM11 (depressurization), KazSat-1 (failure of the control system), Express-AM2 (failure of the solar system rotation system), NSS-703 (complete development of the “working fluid” of the engines of accurate correction) ... And yes, Express-MD1.

It was a regular working day on July 4, 2013. Routine: we looked at the current state of the network and channels, worked with plans for the next extensions and changes, solved some minor problems (something is necessary on a large network). As time went on for dinner, I decided to go pour some tea. And then out of the corner of my eye I saw a bunch of accidents falling out on the screen of the monitoring system.

The simultaneous occurrence of a large number of accidents or accidents in many directions may well be, for example, a shower at one of the central stations. But here I see that at the same time the channels crashed, landing in both Ulan-Ude and Vladivostok.

All carriers first sank, then almost recovered, and then very quickly disappeared completely. This is a very characteristic picture for the case when the satellite loses orientation. Therefore, dialing the duty number of the GPKS duty service, I was already preparing to hear the worst.

A bit about the network

Before continuing the story, it is worthwhile to clarify that satellites are piece-wise products manufactured almost by hand, having backup of all vital systems and cost crazy money. However, anything that can break will break.

All accidents and problems with satellites can be very conditionally divided into two parts: removable (but which, nevertheless, can lead to a partial loss of working capacity or functionality) and fatal - those that lead or can lead to a complete loss of working capacity (up to or the death of the entire apparatus).

A typical recoverable accident is a failure of a unit or system for which a standard reserve is provided. It is clear that the possibilities of redundancy are not unlimited. And if, for example, the primary and backup transmitters fail sequentially, then the trunks served by these transmitters will stop working. But still, this is only a partial loss of functionality, because the rest of the trunks, working through other transmitters, will continue normal operation.

The most common accidents that lead (or can lead) to a complete failure are problems with engines and orientation systems, problems with the power supply system and problems with the satellite control system. And the hallmark of almost all such accidents is the "spin of the satellite." In the normal state, the satellite is directed exactly to the Earth. Tracking the position is the task of the stabilization system, which determines the position of the satellite relative to the Earth and stars. The same system controls gyroscopes, which, in fact, provide constant stabilization of the satellite in three planes. Imagine now that on board the food “blinked” for a short while. What will happen next? That's right, the gyroscopes will start to slow down. And the satellite at the same time, according to Newton’s third law, will begin to crank, and almost unpredictably.

It is clear that when “cranking” all services also stop working. And not even because the antennas are now not looking where they should, but due to the fact that in such emergency situations, satellite automation first of all shuts off all the payload, trying to save battery power as much as possible.

Again July 4, 2013

The RSCC confirmed the presence of problems with the satellite, but there was no specifics (the official confirmation of the accident and its alleged causes were announced only three days later). Through unofficial channels, my conjecture about the satellite’s loss of orientation was confirmed.

But no one had any information about the prospects of regaining control over the satellite: too little time has passed, and it takes at least several hours to assess the causes, possible consequences and a plan of possible actions.

We began to slowly collect all the information in one place: the stations and their channels, the equipment at these stations and its capabilities, the ability of the antennas to rotate from 80E to other positions, possible landing points, the presence of the necessary equipment on them, possible transition scenarios, band and energy required to turn on the Express-MD1 channels ... Fortunately, we had only one transponder on this satellite, however, there were 12 satellite earth stations operating on two central stations: Vladivostok and Ulan- de. And we had to figure out where and how to shove these channels into our existing tank on other sides.

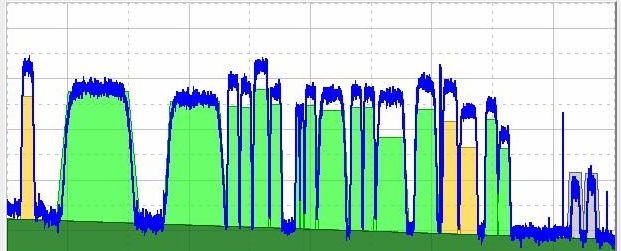

We have a fairly large satellite network. And the capacity for it we rent is not "channel", but we take from the owners of the sides in large enough pieces. Therefore, almost always we have a certain margin in capacity: a band that is not currently occupied by channels. But firstly, there are not so many such "surpluses" (expensive indeed!), And secondly, almost always this free capacity is not a single unit, but pieces of strips between working carriers. A typical transponder loading picture looks something like this:

Each “stick” is one carrier (or one channel if modems with correlation compression are operating on the line), the width (and height) of which depends on the channel speed, the modulation used and the codec, and the size of the SSSC antennas. Is it possible to put another, say, a third of what is already there in this trunk? Well, if you really try ... But at least for this you need to collect all the voids in one place. Further, if we have several trunks on this satellite, and other trunks also have at least some empty space, you can transfer several carriers / channels from the trunk to the trunk (again, collecting all the empty space in pieces suitable for use). But you can shuffle the channels along the trunks, if this allows you to make the equipment of both ZSSS - there are also limitations there.

And if he doesn’t allow it, then maybe there is another station that looks at the same satellite, which has no such restrictions, and where can the channel be landed (with its subsequent return on the ground)? Or maybe in this or in the next trunk you can win a little more strip due to the "exchange of the strip for energy"? Or, maybe, there is a way to quickly take away one ZSSS with a large number of channels - from this satellite to some other, and to take away the injured in its place? And if possible, then what, how and where to land, whether there will be the necessary equipment, whether there will be capacity in the ground to enable / return services ... All these options had to be invented, sorted, analyzed and calculated, thought over all the multi-paths like “if if we do it like this, it will turn out like this ”, and“ if it doesn’t work like that, then like that, this way and that. ” In a word,

For all these “tag games” it took us more than a day of almost continuous work. And in the end, by the evening of July 5, we had the first version of the plan of salvation. According to this plan, the main part of the channels was diverted to Express-AM33 (with the UHF-Ulan-Ude CZSSS turning from MD1 to AM33). At one point there were two antennas (S / Express-MD1 and Ku / Yamal-301), this direction was diverted to Yamal with its simultaneous re-landing from Ulan-Ude to Irkutsk. Another station was diverted to NSS-9 with re-landing from Vladivostok to Khabarovsk. And one more disconnected completely (the traffic was transferred to a relay that arrived very on time, the commissioning of which was expected just the other day). At the same time, at several stations it was necessary to change the modems to be able to work in the mode of correlation compression. At the same time, a test Ulan-Ude U-turn was made on Express-AM33. I had to make sure

On the 6th of the year, the GPKS launched the emergency Express-AM2, which stood at the same point. This was done primarily to save TV broadcasting. Express-AM2 itself was turned off at the time due to problems with solar panels (yes, the same one from which we also had to run away). Therefore, it turned on for a very short time and at a lower power. Nevertheless, this was clearly better than a complete lack of communication, so we returned Ulan-Ude for a while. And they began to prepare the Moscow antenna, which was not used at that time, in order to provide temporary landing of the ZSSS channels remaining at position 80E (Express-AM22), after the Ulan-Ude ZSSS was reconstructed to Express-AM33. Well, yes, the best option is to turn all the ZSSS at once. But you still have to somehow get to them ...

July 8: some math and roulette

By July 8, the study, preparation and assembly of ground connections for re-landed channels was completed, the available human resources were once again recalculated (all who had ever seen a satellite dish were put under arms), their travel routes were determined (for Siberia, where half points are shift camps, this is very important). The people ran for tickets. The longest trip (taking into account the return time) was two weeks. At the same time, work was done on clearing and releasing the band on the satellites, where the stations were to be transferred: assembling all voids in one piece, translating from trunk to trunk, changing channel parameters, changing frequencies - and again collecting voids in one piece. A lot of iterations - just because all the permutations, shifts and reconfiguration had to be done with minimal interruptions in the operation of the moved channels. Customers using these channels are certainly not very interested in the fact that a nearby satellite was killed.

Well and most importantly - plans and instructions. Searching for a satellite, pointing the SSSS on board and reconfiguring the equipment are simple, but still specific tasks. And their implementation requires not only knowledge and experience, but also instruments and tools. In fact, it turned out that a number of stations would have to be twisted by people who have something but lack (there is experience, but no devices, or vice versa). An impossible task? Not at all: in this case, it helped a lot that the ZSSS were already set up, only on the other side. That is, it was not necessary to rummage around the sky in search of a satellite, it was only necessary to very accurately shift the antenna by the desired number of degrees (well, and then fine-tune it more precisely, already under our guidance and along the working channel). You will not believe, but for the exact “displacement” of even a relatively large antenna using this technique, ordinary roulette is quite enough! Well, clear instructions: what and how to measure, where to put the risks, how to twist the antenna to these risks ... Everything is important here, up to the order of the release and tightening of the nuts. A separate instruction was prepared for each ZSSS with regard to the type of antenna used and the installed equipment: with pictures / photos, displacement plates, target designations (at least for verification or “if something goes wrong”), a plate of variable configuration parameters, etc.

July 9–15: recovery

The last channel was restored on July 15. A lot of scribble, a lot of nerves, by the end of the day the throat is already screaming from constant telephone conversations. And for some - all night on the plane, from the plane to the helicopter, then to the shift, then blindly tune the antenna - and again to the shift, helicopter, to another station ...

PS "I told you: the place is damned"

A bit of mysticism. The point of 80 degrees east longitude is definitely some kind of unlucky for Russia. Judge for yourself: the last satellite that worked without an accident and adventure in this orbital position from and to (and even noticeably more) is the Soviet Horizon. What next:

- Express-2, launched at this point to replace the "Horizon", is the failure of the engines of accurate correction, the inability to stabilize the satellite in orbit. The satellite itself has worked for a very long time in inclined orbit mode (ZSSS working through such satellites must have an auto-tracking system behind the satellite);

- Express-AM2, which replaced Express-2, is a failure of the solar control mechanism, the inability of the satellite to work around the clock under load. Emergency replacement with the "small satellite" Express-MD1;

- the planned replacement of Express-MD1 should have been made a full-fledged heavy satellite Express-AM4. Crash of the upper stage, threat of collision with Express-MD1 (then still operational), loss of satellite;

- after the unsuccessful withdrawal of Express-AM4, Express-AM4R was launched after him. Explosion of the 3rd stage of the launch vehicle at launch.

- And, finally, Express-MD1 - loss of orientation, termination of work.