What the Count of Monte Cristo Can Tell Us About Cybersecurity

- Transfer

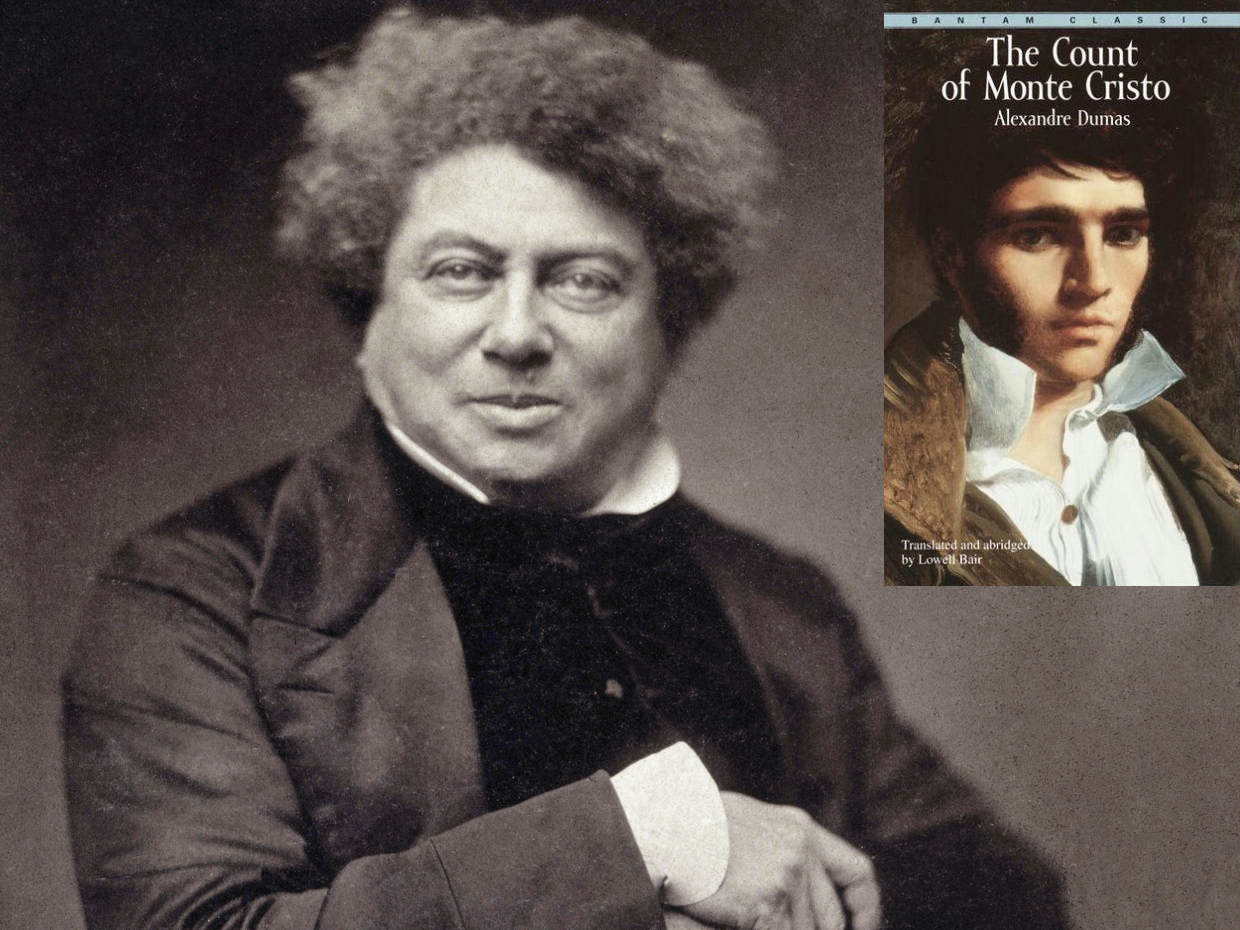

In 1844, Alexander Dumas described a telecommunications hack based on insider threats and social engineering.

What can a 174-year-old French novel have to say about cybersecurity? It turns out a lot. Alexander Dumas novel “The Count of Monte Cristo ” was published in 1844, and he, of course, knew nothing about the Internet, and probably understood little about electricity. But the writer perfectly understood the human nature and how people interact with technology, and foresaw how a technological attack could be organized by abusing personal phobias.

In the center of the book is such a telecommunication technology as the telegraph, although not familiar to us with the electric telegraph - it was being developed at the very time that Dumas was writing his novel. In 1837, Chals Cook and William Wheatstonedemonstrated their electric telegraph system in London, and Samuel Morse patented the idea of telegraph in the United States.

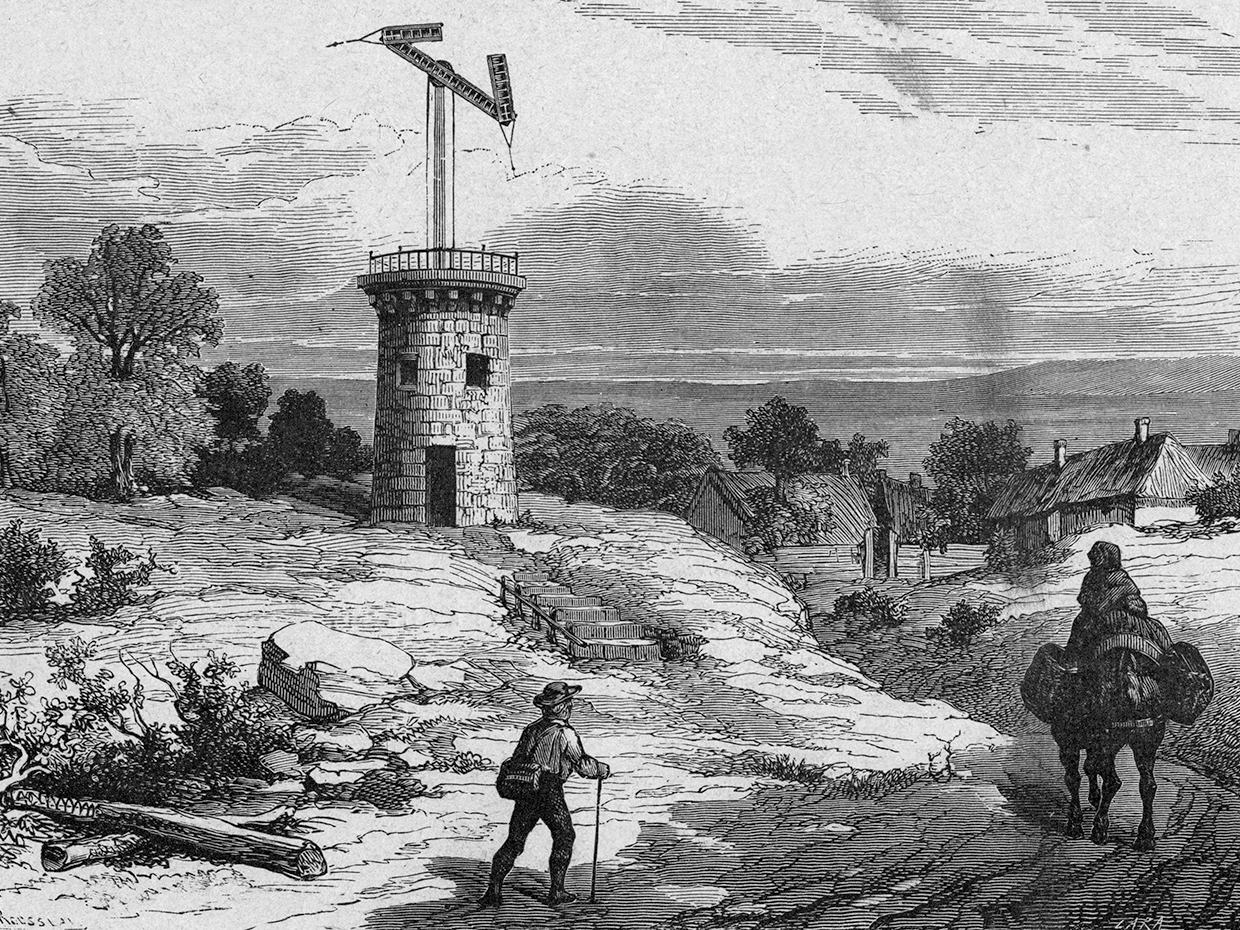

1793 engraving of the optical telegraph tower - part of the national network used by the French revolutionary government

The Monte Cristo Count uses an optical telegraph. Since the 1790s, the French have built and used this long-distance communication system, which eventually stretched out to form two main lines - one from the English Channel to the Mediterranean Sea, and the other from Spain to Belgium. Each consisted of a sequence of towers, between which was about 10 km. At the top of each tower was a semaphore - a large rotating crossbar with short levers at the ends. When transmitting a message, each operator adjusted the semaphore so that it coincided with the semaphore of the previous tower; the operator of the next tower did the same, and the message in this way was transmitted along the chain.

Claude Chappe, French engineer, inventor of the telegraph system with visual semaphore signals.

The leading engineer of this system wasClaude Schapp , who took the idea from the semaphore flags that were used to transmit military messages from the time of Alexander the Great. Shapp developed a system of cables and blocks for controlling a semaphore, created code that simultaneously compresses and encrypts messages, and wrote the rules for working with it, which, among other things, allowed operators to change the direction of messages.

The optical telegraph appeared during the French Revolution. Schapp began his experiments on the telegraph shortly after the riot and the capture of the Bastille and in 1789. After the executions of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinettethe revolutionary government decided that it needed a national communications network controlled by it. At that time, the only method for sending messages over long distances was the postal service organized by Louis XIV, which continued to be strongly influenced by the royal family, the aristocracy and the clergy — the three groups that were enemies of the revolution, unworthy of trust.

Schapp's optical telegraph eliminated the enemies of the revolution from the messaging system, and replaced them with ordinary citizens who were paid a modest salary for work at semaphore stations. Dumas described them as “miserable poor people,” who obeyed strict discipline, who needed to be on the post from dawn to dusk, and to spy on their colleagues, marking each incorrectly transmitted character. “I have no responsibility,” says one operator at the Monte Cristo Count. “I, therefore, the machine, that's all.”

The telegraph hacking method invented by Dumas was fairly predictable. The Count, a man who was unjustly imprisoned in his youth, puts in a telegraph a false message, which should destroy one of the dishonest people who treated him. He does this by bribing the operator, giving him enough money so that he can leave the telegraph service, avoid punishment, and start life anew in another place. The obvious morality is that people are often the weakest link in a technological system.

However, Dumas also revealed the second weak link in the system. The count needed more than just tossing false information. He needed to do this so that this lie was taken for the truth. No technology, no matter how new and omnipotent it is, can automatically make transmitted messages the truth. Telegraph recipients would criticize and evaluate any information that fell into their hands. To emphasize this, Dumas filled the book with characters who did not trust the telegraph. “You think you know everything, because the telegraph told you this,” says one character to another. “Believe me, we are no worse informed than you.”

The count makes his message look like the truth, using the second human weakness contained in the French telegraph system. He notes that the wife of his victim is friends with a government secretary with access to the telegraph. The secretary never speaks, but “stockbrokers immediately shorthand” his words. However, something in the behavior of the secretary suggests that he has something to hide. Dumas calls it "restlessness of the mind." The Count uses this concern. A private conversation with the count forces the secretary to agree to transmit the false message to the victim's wife, who passes it on to her husband. This completes the plan of the graph.

This is how old technologies can give us universal lessons in a simple and understandable language. The weak link of the French telegraph was not unique: all communication systems rely on service personnel, who must obey the rules of work and organizational discipline, while being subject to external influences. As Dumas’s history indicates, these systems are also vulnerable to security risks that go beyond staff.

Readers of the Count of Monte Cristo naturally want to empathize with the hero, the person who ultimately gets what he wants: wealth, knowledge, and revenge for his pursuers. However, Dumas says that we, readers, may not be a hero - we may be an operator who gives in to a bribe, or a secretary who agrees to undermine the telegraph. Technical weaknesses can be found in all communication systems, but often the weakest spot is in the people who manage and use these systems.