Dan Saffer - Microinteractions. Book abstract

- Transfer

- Tutorial

“Details are not details. They create the design. ” - Charles Eames.

“Details are not details. They create the design. ” - Charles Eames. The success of digital products is determined by little things. Dan Saffer's book Micro- Interactions will teach you how to design effective functional elements. And this detailed compendium will help to better remember what has been read or even replace the English-language original.

How can the user change the setting? How to turn on silent mode or learn about receiving a new message?

Using vivid examples from real-life modern devices and applications, the author parses microinteractions into components and shows how to use them in mobile applications, web widgets, and home appliances.

Key points for those who have not mastered the entire post

- Microinteractions are small elements of functionality. Focus on them is very important. The quality of a product’s design is determined by the quality of its smallest details.

- Microinteractions consist of four parts: trigger, rules, feedback, and cycles / modes.

- There are three approaches to working with microinteractions: focus on each microinteraction separately, simplification of the function to the key microinteraction, and a look at the function as a set of related microinteractions.

- The trigger initiates microinteraction. It can be user or system. The trigger should: do the same action every time, show data, do not break affordance (visual hints for direct manipulation), be more noticeable for more frequent actions.

- The rules determine what, how and in what order can occur. They should: define restrictions, do not start from scratch (use data from the environment, etc.), replace options with default values, determine the states of all objects, do more with fewer elements, prevent errors, use a short “human” text.

- Feedback explains the rules to the user. Determine what information and when can be useful to the user. Use humor, existing elements for messaging, communication with the control. Use the visual channel whenever possible. Strengthen it with sound or vibration if desired.

- Use modes for rare operations. If possible, use separate screens for them. For quick action, use spring-loaded or one-time modes.

- Cycles extend the life of microinteractions. Use long loops to endow micro-interactions with memory, or to gradually hide or reveal aspects of micro-interactions.

Abstract

Table of contents

Chapter 1. Design of microinteractions

- Microinteractions are not product features, but still important

- Microinteractions can be large

- The Secret History of Microinteractions

- The structure of microinteractions

- Microinteractions as a philosophy

Chapter 2. Triggers

- Custom triggers

- Show data

- Trigger Components

- Controls

- Invisible Triggers

- Tags

- System triggers

Chapter 3. Rules

- Formation of rules

- Nouns and Verbs

- Screens and Statuses

- Limitations

- Don't start from scratch

- Amortize complexity

- Limited options and smart defaults

- Error prevention

- Microtext

- Algorithms

Chapter 4. Feedback

- Less is more

- Feedback as a mechanism for transmitting personality

- Feedback methods

- Visual

- Sound

- Tactile

- Feedback Rules

Chapter 5. Cycles and Modes

- Modes

- Spring-loaded and one-time modes

- Cycles

- Long cycles

- Progressive disclosure and concealment

- Example 1: Mobile alarm application

- Example 2: General online playlist

- Example 3: Dishwasher Control Panel

- Prototyping and documentation of microinteractions

- How to improve boring microinteraction

- Micro Interaction Testing

Chapter 1. Design of microinteractions

In 2012, the iPhone’s alarm went off at the time of the concert with the well-known patron of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. The patron could not understand for a long time that this was his phone, because he was sure that the alarm clock could not work in silent mode. The concert was disrupted, the precedent made a lot of noise. Putting your phone into silent mode is an example of microinteraction.

Microinteraction is a tiny element of functionality that performs one action.

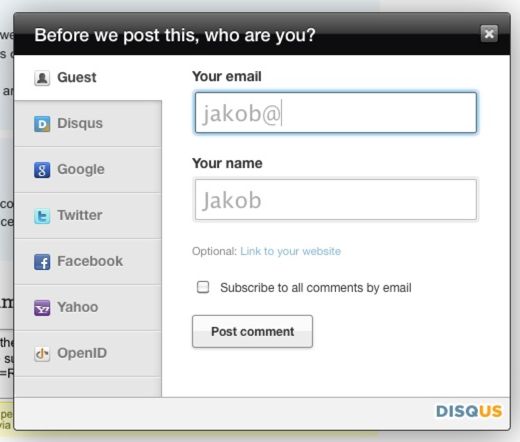

Another example is the auto-complete name based on e-mail during registration:

Microinteractions are not product features, but still important

Microinteractions are often invisible and are integral parts of product features. For example, a music player is a function, and volume control is microinteraction. The product is rarely bought due to its microinteractions, but they are very important. The design quality of a product is determined by the design quality of its smallest details. The higher the competition in the market segment, the more important the microinteractions, as they highlight the product against the background of functional equality.

Microinteractions can be large

An example of large microinteraction is a toaster.

Microinteractions also allow you to link product versions across platforms. For example, the micro-interaction of sending a tweet connects Twitter mobile, desktop and web clients.

The Secret History of Microinteractions

In 1974, Larry Tesler began developing the Gypsy text editor, whose goal was to reduce the modality of the user interface so that users did not need to switch modes to perform different actions. Pressing a key should always print this key, and not be interpreted by the program differently depending on the current mode. Thus, the copy-paste microinteraction was born without changing the mode.

The whole history of designing interactions between a person and a computer is a history of microinteractions. Scrolling and opening windows, creating folders and files, connecting to WiFi, saving documents are all examples of microinteractions that someone should have come up with.

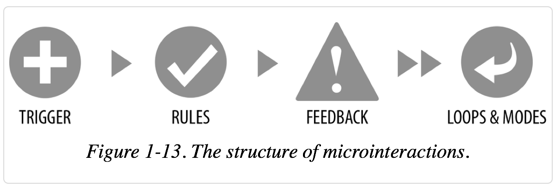

The structure of microinteractions

Microinteractions consist of four parts:

- trigger (initiates microinteraction);

- rules (determine how microinteraction works);

- feedback (OS, explains the rules);

- cycles and modes (meta-rules that affect microinteraction).

Microinteractions as a philosophy

When designing a new or improving an existing product, determine what micro-interactions it contains. For each microinteraction, clearly define its structure and try to improve each component.

Signature Moments are the micro-interactions that make a product stand out. Examples: the scroll wheel of the original iPod, the sound “You've Got Mail!”, The unusual progress indicator “Loading ...”. Characteristic features improve the recognition of the product and increase the loyalty of its users.

Microinteractions are exercises in limitation. Use them as a product development strategy through the mantra “less is more.” Reduce the product to its very essence, its Buddhist nature. A “minimum viable product” (MVP) can sometimes be reduced to a single microinteraction.

You can also look at the product as a set of microinteractions working in harmony. Details are design. They are the standard by which product quality is measured.

In other words, there are three approaches to working with microinteractions:

- focus on each microinteraction separately;

- simplification of the function to key microinteraction:

- a look at the function as a set of related microinteractions.

Chapter 2. Triggers

The first principle of triggers: a trigger must be recognizable by the user within the context. The user must immediately understand that something can be done with the trigger. For example, a subway card splash screen in New York is one big button. The interface of this machine was at one time a great success.

Custom triggers

User triggers must satisfy the user's need. Example: “I want to put the phone into silent mode”, “I want to buy a metro card”. It is fundamentally important to understand three things:

- what the user wants to do;

- when he wants to do it;

- in what context does he want to do this.

This understanding determines when and where the trigger will be displayed. For example, the formatting toolbar in Microsoft Office appears only after you select text.

The second principle: the trigger must be the same every time. The Home button on iOS is an example of a violation of this principle. The first press switches to the home screen, the second - to search. ( Note by the composer: this has been fixed in iOS 7 )

The most ineffective triggers are triggers hidden in drop-down menus.

Show data

The third principle of custom triggers: they should show data (Bring the data forward). Think about what kind of data a trigger can show about the internal state of microinteraction before it starts or during execution. For example, the Google Chrome icon displays the number and progress of downloads.

Trigger Components

Custom triggers consist of three components: the control itself, its state (default, roll-over, hover, active), as well as a text or iconographic inscription (label):

Controls

The purpose of the trigger control (as well as the entire microinteraction) is to minimize the user's choice by offering smart defaults and a limited set of options. Example: On / Off switch.

The fourth principle of triggers: do not break the visual affordans (visual hint for direct manipulation). If the trigger looks like a button, then it should work like a button - i.e. it’s important that you can click it.

Fifth principle: the more often microinteraction is used, the more noticeable should be its trigger. When we look for something, our field of view narrows to less than one degree (less than 1% of the normal state). Vision in this sense is similar to a searchlight. When recognizing objects, our eyes look for familiar shapes - geons. Geons are simple shapes (squares, triangles, cubes, cylinders) that the brain combines in order to understand what kind of object is in front of it. Given this brain feature, it is important that triggers, especially icons, have a geometric shape.

Sixth principle of custom triggers: do not make false afforces. The user does not have to guess how the trigger works. Try to use only standard controls.

Invisible Triggers

Triggers can be invisible. Examples: gestures in touchscreen interfaces of smartphones, voice control Apple Siri and Google Glass.

Invisible controls should be detectable whenever possible. For example, a list update can be detected when you try to scroll the list above the first item.

Tags

The seventh principle of custom triggers: do not use an inscription if it does not carry additional information. Example: five rating stars instead of a slider with five inscriptions.

It is important that the inscription is understandable. An example of an incomprehensible inscription: Google search button “I'm Feeling Lucky”. Another example of an unsuccessful caption is the Submit button. Most usability problems are caused by bad labels (or lack thereof).

System triggers

Not all triggers are custom. Moreover, we are probably entering an era when most triggers are triggered by the system, and not by the user. These are triggers that fire when certain conditions are met without the conscious participation of the user. For example, the delivery application determines that there is a tracking number in the buffer and offers to track delivery.

Typical conditions that can trigger a trigger:

- error (dialogue in case of loss of communication),

- location (Foursquare offers a check-in)

- incoming data (“You've got mail!”),

- internal data (decrease in screen brightness after a few minutes of inactivity),

- other microinteractions (in the wizard interface, the end of one step is the beginning of another),

- other people (notification when responding to a tweet).

The user should be able to turn off system triggers through the setting and, preferably, for the first time when the trigger appears (“Do not show me this warning again”).

Chapter 3. Rules

In Mac OS X 10.7, Apple has radically changed the logic of the microinteractions of the Save and Save As functions, faced with negativity and misunderstanding, and after that made new changes that completely confused everyone.

Two lessons:

- If you cannot easily create a diagram of the rules of microinteraction, then users will not be able to compose its speculative model.

- Radically new, unexpected microinteractions can be used only when the benefit from them is much higher than from the old, familiar ones. Example: adding @ to the keyboard when entering email in iOS.

A key component of the rules is the user's goal. For example, the purpose of authorization is to enter, not enter an email and password.

The rules determine:

- response when the trigger is activated,

- the ability to control the user,

- sequence of steps

- data used

- configuration of the algorithms used,

- feedback rules

- modes

- repetition rate (if any)

- actions at completion.

For example, a lamp with a motion sensor:

- Check for movement every 3 seconds.

- If there is movement, is it a person (judging by size)?

- If so, turn on the light.

- Check for movement every 3 seconds.

- Is there any movement?

- If not, wait 10 seconds and turn off the lights.

Example in Pages.app: the Heading 3 heading appears in the styles list only after the Heading 2 heading has been used in the document.

Formation of rules

The easiest way to formulate rules is to write out all the rules that you know about microinteraction. Usually these are microinteraction steps in the order of their execution.

Shopping basket example:

- On the product page, the user clicks “Add to Cart”.

- The item is added to the cart.

Nouns and Verbs

Microinteraction can be presented in the form of a proposal. Verbs are user actions, nouns are action objects. Example: “volume up or down slider”. The rules determine the states and characteristics of nouns (for example, the maximum number of elements in the drop-down menu), as well as the status of verbs (for example, the time the action takes).

Screens and Statuses

It is tempting to select a separate screen for each step of microinteraction. But this approach only works well in special cases such as wizards. For most microinteractions, it is not the screens that need to be changed, but the state of the objects within a single screen.

For example, in the case of drag-and-drop, the initial state of the object looks like it is being dragged (by itself or when you move the cursor). In the process of dragging the state of the object changes. The state of the screen can also change, showing where you can drag the object. The state returns to the initial state when pulling is completed.

Limitations

Rules must consider constraints (business logic, technical, environments). Examples: what input tools are available, what type and range of input data, what resources are expensive, what data are available (location, WiFi availability, weather), what behavioral data can be collected for future use.

Don't start from scratch

The first question to ask when activating a trigger is: “What do we know about the user and the context?”. For example, Eventbright automatically increases the brightness of a device for scanning a QR code from it.

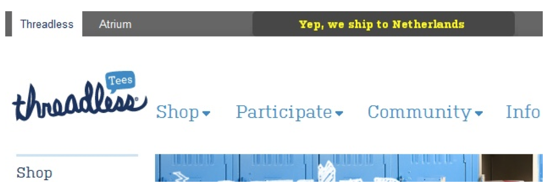

Examples of data that can be used: platform / device, time of day, noise in the room, time since the last use of this microinteraction, whether the user is in a meeting, alone, battery power, location and direction of movement, user actions in the past. For example, Threadless, based on the user's location, immediately shows whether delivery is possible. Pro Flowers shows you the nearest holiday when choosing a delivery date. Dropbox shows different download instructions depending on your browser.

When collecting user information, it is important to keep a balance and not to invade his privacy.

Behavioral data collection and analysis can also help add features for advanced users. For example, in Waze, you can slide (instead of pressing) buttons to save two clicks.

Amortize complexity

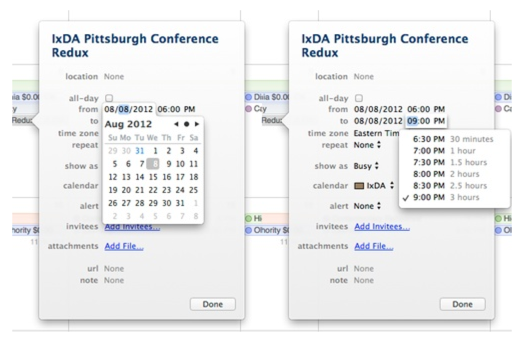

All actions have inherent complexity, i.e. There is a limit to simplification. The question boils down to on whose shoulders this complexity lies - the system or the user. In the case of microinteractions of the user, it is better to deprive the choice and the need for decision-making. For example, when choosing an end date for an event, iCal shows its duration, removing the need for unnecessary calculation from the user.

Limited options and smart defaults

The fewer decisions a user needs to make, the clearer the microinteraction. It’s good practice to highlight the next step or action, either by reducing the number of alternatives, or through a visual accent (for example, by highlighting the size / color of the button).

Better yet, take this step for the user. For example, YouTube automatically stops playing a video when you click the Report button. Pintrest automatically inserts text from the buffer into the header field.

The choice of the default value should be determined by the frequency of use of this value. Example: highlighting the OK button in the OK / Cancel dialog.

Error prevention

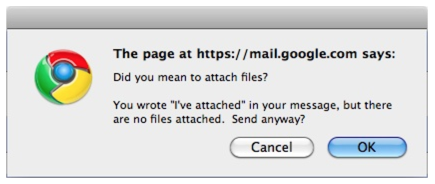

Products and processes should be designed so that the user does not have the opportunity to make mistakes. Lightning cable in iPhone can be connected either side (unlike USB). Gmail warns about the absence of the attachment mentioned in the letter.

Errors should only be shown in cases where the system itself cannot fix them. For example, Meetup automatically expands the search radius if nothing was found in the specified radius. Twitter does not send the same tweet twice in a row.

Microtext

In any microinteraction, first of all, you need to make sure that the text is mandatory. For example, the text “Please Login” above the login form is superfluous, if it is already clear what needs to be done next. The text “Click to continue” is not needed if there is a “Continue” button.

Algorithms

In the case of a music recommendation service, the algorithm is determined by the following questions: Does the genre coincide? Should new tracks be higher than old? Did the user listen to these tracks before? If so, they need to be excluded. Genre, album, performer, correlation of new music and old - these are all variables of the algorithm. It is useful for the user to know which variables are involved in the algorithm. For example, knowing the principle of scoring in FuelBand can help the user to take actions that lead to points increase.

Chapter 4. Feedback (OS)

Slot machines are a multi-billion dollar business, significantly superior to cinema, video games and even pornography. And it is completely based on the OS, through which reinforcement occurs at a variable interval. People play non-stop, as payments are unpredictable, and there is a chance to hit the jackpot. Conclusion: OS is a very powerful tool.

With microinteractions, the opposite is true - the OS should be predictable and should positively reinforce the desired effect.

The first principle of feedback in microinteractions: do not overload the user. The OS should be as small as possible in order to explain what is happening.

The OS makes the rules of microinteraction understandable to the user. Always look for the opportunity to add the OS where it can clarify what is happening. For example, Quora shows when someone answers a user-viewed question right now. The Boxee logo changes to a sad face if there is no internet connection. A Threadless basket smiles when it has goods.

Information transmitted by feedback can sometimes be obtained only through an action or an error. This is normal, because from the point of view of neurobiology, training occurs when the expectation does not correspond to the real outcome. It is important that the error does not have negative consequences. For example, opening the door of the dishwasher without understanding the flashing indicator should not result in a burn of hot water.

The second principle of feedback: it should not be arbitrary. The OS must be associated with the trigger. For example, pressing the power button of the device should not lead to an arbitrary sound, since there is no direct connection between the sound and the button. It is much better if the press is accompanied by a typical click or sound characteristic of turning on the device (for example, a note with a growing pitch). Ideally, the OS should flow from the rule, which in turn follows from the trigger.

Less is more

Third Feedback Principle: Use pre-existing elements to convey a message. For example, in OS X, the window resize cursor changes when resizing is only possible in one direction.

OS as a mechanism for transmitting personality

Unlike more utilitarian triggers, feedback can be diluted with humor. For example, Dropbox offers refreshments while a long download is in progress. Siri answers with a joke questions like “What is the meaning of life?”

Feedback methods

Visual

The visual OS should be as low as possible for message transmission and should not be redundant. For example, a tooltip should not duplicate the text of an inscription.

If the visual feedback is shown away from the scene, you can draw attention to it by movement (for example, through a gradual appearance).

Animation should be informative. For example, the spinning speed of a network connection spinner on an iPhone depends on the network speed. It should also be short. A good rule of thumb is to make the animation immediately two times shorter than you expected. After that, speed up the result two more times, if possible.

Do not use the words “error” or “caution” in feedback. They do not contain useful information and may annoy or frighten the user.

Do not use personal pronouns. The phrase “Password is incorrect” is better than “You entered the wrong password”.

The fewer words, the better. Focus on the action the user must take. Example: “Enter the password again.”

Sound

The response time of the brain to a sound OS is significantly longer than to a visual one.

Sound is usually used in two cases: when an error occurs and to emphasize an action (for example, clicking when a button is pressed). In the case of emphasis, a sound OS is usually combined with a visual one. It has been proven that such a union is more effective than just a visual OS.

With sound, as with other methods, context is important. For example, sound may not be desirable at night.

You can use either words or sound icons (earcons) to sound the message. It is desirable that the sound icon evoke an association associated with the transmitted message. For example, the sound “whack!” can be used when moving an item up the list.

If you want to make a memorable Feature of your product from a sound icon, then use from two to four consecutively playing notes.

Do not use similar sound icons for different actions.

When using voice instructions, complete the sentence with the required action. Option: “To turn off the sound, say“ yes ”will be preferable to“ Say yes to turn off the sound. ”

Tactile

Tactile OS is capable of transmitting only 1% of audio information. Most people can only distinguish 3-4 levels of vibration.

A tactile OS is used in three cases: to complement an action (for example, pressing a button), to notify when sound is turned off, and to simulate a texture (for example, to slow down scrolling).

Feedback Rules

- Context dependent (e.g., lower volume at night)

- duration (how long and when it ends),

- intensity (brightness / speed / volume / vibration),

- repetition (how often, what is the termination criterion).

Chapter 5. Cycles and Modes

In 2004, the Spirit rover went into emergency mode after a software update crash. He was overloaded, faced with a lack of space problem and was overloaded again, trying to eliminate this shortage by rebooting.

Mode (in the case of Spirit - emergency mode) is a special state of the application in which its operation differs from the standard one. For example, actions such as keystrokes can produce irregular results.

A cycle (in the case of Spirit - endless reboots) is a repeating command or sequence of commands.

Modes

A mode is an offshoot in a rule. The fewer modes in microinteraction, the better. In most cases, modes are not needed at all.

The key disadvantage of the modes is that they lead to user errors. Especially in cases where the transition to the mode is invisible from the point of view of the interface. It’s good practice to use separate screens for the modes. At the same time, it is useful to highlight the regime change by a noticeable transition. Example: choosing cities in the weather application in iOS.

Spring-loaded and one-time modes

Spring-loaded mode (also known as quasi-mode) is available at the time of a physical action such as holding a key or mouse button. Classic example: holding Shift to enable caps lock mode.

In a single mode, an action automatically turns off the mode. For example, in iOS, double-clicking turns on the cut-and-paste mode, which automatically turns off after selecting a command.

Cycles

The cycle is set by the rules. For example, “receive data every 30 seconds” and “send a reminder after 10 days”.

The cycle can be used to limit the duration of the action. For example, end an online banking session for security reasons.

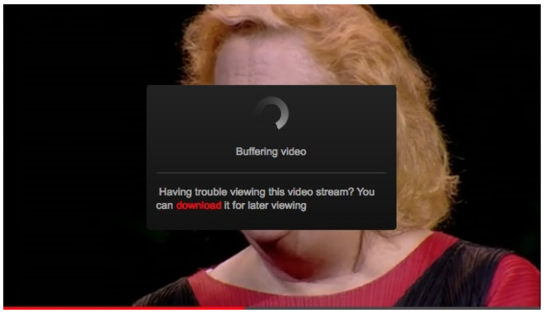

The loop can be used to determine the action. For example, in the case of a long pause at a certain step, the user may be offered help. The TED application offers to download the video for later viewing if buffering takes too much time.

Long cycles

Long cycles can improve microinteraction over time. For example, reusing the player may take into account the latest volume setting.

Progressive disclosure and concealment

Long cycles can be used to gradually reveal the possibilities of microinteraction. For example, after several uses, keyboard shortcuts or advanced features may be added. Conversely, microinteraction can be simplified as you become familiar with it. For example, in Layer-Vault, the signature button first has a large size and label. As you use it, the inscription goes away, and the button itself decreases.

Chapter 6. Putting It All Together

Example 1: Mobile alarm application

We’ll design an alarm clock application for iPhone. The entire application is one micro-interaction setting the alarm time.

Rules:

- The user selects a time.

- The alarm goes off at the selected time.

- User turns off the alarm.

Trigger: application icon on iPhone home screen.

The first question is how to show the data? iOS allows you to show only integers on the application icon. It would be logical to show the selected alarm time, but with integers it turns out not very clear. In the case of triggers, clarity cannot be sacrificed, therefore, we will show the number of set alarms.

The second question is how not to start from scratch? We know the platform, sensor data (camera, microphone, accelerometer, compass), location, set alarms, the frequency of setting alarms in the past, the distribution of alarms by day, actions when the alarm goes off. Based on this data, you can add new rules:

- Use the 24-hour format if selected in the phone’s settings.

- Если за неделю пользователь ни разу не пользовался кнопкой Snooze, убрать ее из интерфейса.

- Предлагать пользователю время, если он использовал его 3 раз до этого.

- Отображать выставленные будильники. Показывать время до срабатывания будильника.

The penultimate rule is an example of a long cycle. The latter is an example of error prevention (the time before the response indicates an error if the user has mixed up AM and PM).

Go to the controls. The main one is the timing. On the one hand, you can use the standard toggle switch used in the Clock application. On the other hand, this is a great opportunity to add character. I always liked the old-fashioned tickers used at train stations in train schedules. We revive them using feedback in the form of a click and a drop under the influence of gravity. Considering that the vast majority does not set the time to the nearest minute, let’s increase the step to five minutes.

Another possibility for catchy characteristic features is the non-standard sound of the alarm clock and the sound effect when it is turned off.

We pass to modes and cycles. For setting the time, a one-time mode is well suited: the user clicks on the alarm in the list, the alarm screen opens, the user changes the time, the screen closes. You could also add the Settings mode, but it is better to replace them with smart defaults. At least in the first release.

The entire application is a single conditional loop. An interesting improvement would be the cycle in which, 2 minutes before the alarm went off, the application through the camera would check the illumination of the room and gradually increase the brightness of the backlight if the room is dark. But on iOS this is not possible.

Example 2: General online playlist

We’ll design a playlist that several people can use simultaneously. Suppose such a playlist is part of an existing music service.

Let's start with user goals. There are two of them: discovering new music and sharing music.

Initial Ruleset:

- When a new song appears, add it to the playlist.

- The user can add songs to the playlist.

- New songs appear on top of the playlist.

Triggers: Add a song by a user (custom trigger) and add a song by a friend (system trigger).

Since a song can be added from anywhere, adding through drag and drop looks like a logical solution. To make this feature noticeable, add an empty cell with the inscription “Drag a song here” to the top of the list. As you use it, the inscription can be replaced by “What are you listening to now?” or even show different labels (“How does your day sound?”, “What is the song of the day today?”).

Are there any other custom triggers? Add a menu item and keyboard shortcut to add several selected songs. One could add the ability to add a song by entering its name, but we already have many different ways, so it’s better not to complicate it. In addition, entering a name is a non-standard way to add a song to a playlist.

Adding a song (especially if the song was added by a friend) is a great place for the OS and, in particular, animation. The added song should shift the rest down. Since the application is musical, the addition can be accompanied by sound.

In the case of a system trigger (adding a song by a friend), a visual OS is needed. We will show the note icon (smiling Notesy character) on the browser tab.

When adding a song, the system may take a few seconds to find a match. A standard spinner could be shown to indicate progress, but it’s better to try using existing elements. Let Notesy look around when the search is in progress.

What data do we show? You can display the name of the user who added the song and the date of addition. The total playlist time and number of songs are also useful information. When adding a song, you can show a comment like “Please, not just another song from the eighties!”.

As a cycle, you can use a reminder to add a song if the user has not added anything for a long time. This can be done either through an unobtrusive indicator of the date of the last addition, or through a push like “Feed me!”.

Example 3: Dishwasher Control Panel

We design a control panel for an inexpensive dishwasher. The goal is to wash plates, glasses and silverware.

Rules:

- The user loads the dishes and detergent and closes the door.

- The user selects a wash cycle and turns on the machine.

- The machine washes dishes.

How not to start from scratch? We know the latest settings, as well as the history of settings. Alternatively, you can select by default the last used mode.

What data do we show? It is important to understand whether the machine is working and how much time is left until completion.

In accordance with the principle of highlighting the next action, the start button should attract attention after selecting a washing program.

Need the ability to reset the program. You can either add a new button or use the spring-loaded mode of the Start button. The second option is better, since dumping will be done extremely rarely. To make the function detectable, add the inscription “Hold to reset” under the Start button.

Prototyping and documentation of microinteractions

There are three ways to describe microinteraction: prototype, video, and storyboard. The prototype is the most effective, but at the same time the most difficult way to implement it.

The most inefficient way is to take static screenshots. They do not convey the dynamics of interaction and remove information about the context, making microinteraction incomprehensible.

How to improve boring microinteraction

If you already have existing micro-interactions that you want to improve, ask yourself the following questions:

- Should it be a feature? In other words, how memorable should be microinteraction.

- Am I starting from scratch? What do I know about the user before the start of microinteraction?

- What are the most important data on microinteraction I can show? What should the user know immediately?

- Уместен ли здесь нестандартный элемент управления? Это будет гарантией выделения микровзаимодействия.

- Предотвращаю ли я человеческие ошибки?

- Использую ли я уже существующие элементы? Есть ли уже существующие элементы UI, которые можно использовать для улучшения микровзаимодействия?

- Можно ли сделать невидимый триггер для продвинутых пользователей? Можно ли добавить шорткат для ускорения прохода по правилу?

- Достаточно ли “человеческий” текст и иконки? Звучит ли текст так, как будто его сказал другой человек? Можно ли добавить юмор?

- Можно ли добавить анимацию? Можно ли добавить переходы между экранами или выделить следующее действие?

- Можно ли добавить дополнительные каналы обратной связи? Звук или вибрацию?

- Что будет, когда пользователь повторит микровзаимодействие во второй раз? А в сотый? Какие могут быть длинные циклы?

Тестирование микровзаимодействий

The user testing process might look like this:

- Before testing, ask the user how they think microinteraction will work. Did he see something similar before? What information would be useful to him before using it?

- Invite him to undergo microinteraction on his own. Record all observations during the passage or immediately after it.

- Follow the microinteraction together in steps, asking the user to comment aloud on all impressions and decisions. Evaluate how well the user understood the rules.

- Ask what should change in microinteraction if the user repeats it tomorrow.

- Conclude with a question: “What one improvement would you make?”.