Artificial Intelligence and Why Doesn't My Computer Understand Me?

- Transfer

Hector Levek wiki claims his computer is dumb. And yours too. Siri and Google voice search are able to understand the prepared proposals. For example, “What films will be shown nearby at 7 o’clock?” But what about the question “Can an alligator run a hundred-meter hurdles?” No one has asked such a question before. But any adult can find the answer to it (No. Alligators cannot participate in hurdling). But if you try to enter this question on Google, you will get tons of information about the Florida Gators athletics team. Other search engines, such as Wolfram Alpha, are also not able to find the answer to this question. Watson, the computer system that won the Jeopardy! Quiz, is unlikely to perform better.

In an awesome article, recently presented at the international joint conference on artificial intelligence wiki , Levek, a scientist from the University of Toronto, dealing with these issues, scolded everyone involved in the development of AI. He argued that colleagues had forgotten about the word “intelligence” in the term “artificial intelligence”.

Leveck began by criticizing the famous Turing Test.in which a person through a series of questions and answers tries to distinguish a machine from a living interlocutor. It is believed that if a computer can pass the Turing test, then we can confidently conclude that the machine has intelligence. But Leveck claims that the Turing test is practically useless, since it is a simple game. Every year, several bots pass this test live in competitions for the Loebner Prize. But the winners cannot be called truly intellectual; they resort to all sorts of tricks and essentially engage in deception. If a person asks the bot “What is your height?” The system will be forced to fantasize in order to pass the Turing test. In practice, it turned out that the winner bots too often boast and try to mislead to be called intelligent. One program pretended to be paranoid ; others showed themselves well in using trolling the interlocutor with single-line phrases. It is very symbolic that programs resort to all sorts of tricks and scams in trying to pass the Turing test. The true purpose of AI is to build intelligence, and not create a program tailored to pass one single test.

Trying to direct the flow in the right direction, Levek offers researchers in the field of AI another test, much more complicated. A test based on the work that he conducted with Leora Morgenstern and Ernest Davis. Together, they developed a set of questions called Grape Schemes , named after the Terry Vinograd wiki , a pioneer in artificial intelligence at Stanford University. In the early seventies, Grapes asked the question of building a machine that will be able to answer the following question:

City officials refused to give permission to the evil demonstrators because they were afraid of violence. Who is afraid of violence?

a) City officials

b) Evil demonstrators

Levek, Davis and Morgenstern have developed a set of similar tasks that seem simple for a reasonable person, but very difficult for machines that can only google. Some of them are difficult to solve with the help of Google, because the question is made up of fictional people who, by definition, have few links in the search engine:

Joanna certainly thanked Suzanne for the help she provided to her. Who helped?

a) Joanna

b) Suzanne

(To complicate the task, you can replace "had" with "received")

You can count on the fingers the web pages on which a person named Joanna or Suzanne helps someone. Therefore, the answer to such a question requires a very deep understanding of the intricacies of the human language and the nature of social interaction.

Other questions are difficult to google for the same reason why the question of the alligator is difficult to search for: alligators are real, but the specific fact that appears in the question is rarely discussed by people. For instance:

A large ball made a hole in the table because it was made of polystyrene. What was made of polystyrene? (In an alternative formulation, the foam is replaced with iron)

a) A large ball

b) A table

Sam tried to draw a picture of a shepherd with a ram, but in the end he turned out to be like a golfer. Who turned out to be like a golfer?

a) Shepherd

b) Ram

These examples, which are closely related to a linguistic phenomenon called anaphora (a phenomenon where some expression denotes the same essence as some other expression previously encountered in the text), are difficult because they require common sense - which is still not accessible to machines - and because they contain things that people do not often mention on web pages, and therefore these facts do not fall into giant databases.

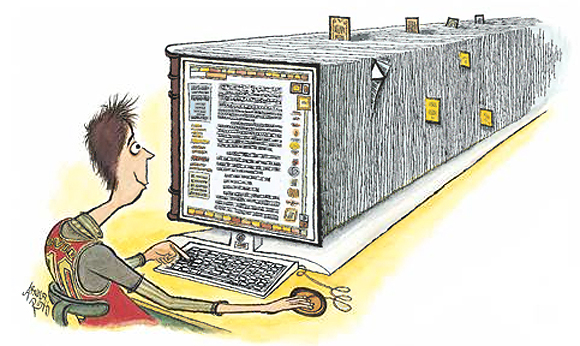

In other words, these are examples of what I like to call the Heavy Tails Problem: common questions can often be answered on the Web, but rare questions perplex the entire Web with its Big Data systems. Most AI programs run into trouble if what they are looking for does not appear as an exact quote on web pages. This is partly one of the reasons for Watson’s most famous mistake - to confuse the city of Toronto in Canada with the city of the same name in the United States.

A similar problem arises in image search, for two reasons: there are many rare pictures, there are many rare picture captions. There are millions of pictures with the caption “cat”; but a Google search can’t show almost anything relevant for the query “scuba diver with a chocolate cigarette” (tons of pictures of cigars, painted beauties, beaches and chocolate cakes). At the same time, any person can easily build an imaginary picture of the desired scuba diver. Or take the query “right-handed man”. On the Web there are a lot of images of right-handed people doing something with their right hand (for example, throwing a baseball). Anyone can quickly extract such pictures from the photo archive. But very few such pictures are signed with the word “right-handed” (“right-handed-man”). A search for the word “right-hander” gives a huge amount of pictures of sports stars, giraffes, golf clubs, keychains and coffee mugs to the mountain. Some are relevant, but most are not.

Levek saved his most critical remarks towards the end of the report. His concern is not that modern artificial intelligence cannot solve this kind of problem, but that modern artificial intelligence has completely forgotten about them. From Levek’s point of view, the development of AI fell into the trap of “succeeding silver bullets” and is constantly looking for the next big breakthrough, be it expert systems or BigData, but all the barely noticeable and deep knowledge that every normal person possesses has never been meticulously analyzed. This is a colossal task - “like reducing a mountain instead of laying a road,” Levek writes. But this is exactly what researchers need to do.

In the bottom line, Levek urged his colleagues to stop being misleading. He says: “There is much to be achieved by determining what exactly does not fall within the scope of our research, and admit that other approaches may be needed.” In other words, trying to compete with human intelligence, without realizing the full complexity of the human mind, is like asking an alligator to run a hundred-meter hurdles.

From translator

I was interested in Levek's critical view of modern Siri and Google. Intelligent search engines have learned to imitate the question that users ask. But they are still infinitely far from the AI about which they make films and write books.