About one error

Maybe I'm wrong, but I firmly adhere to the opinion that some errors are no less interesting than the projects in which they occurred. I want to talk about one project in which I took part for a long time. The fact that the correct use of cryptographic tools would seem to have led to a vulnerability that deprived the rest of the cryptography of any meaning.

I will say right away that I myself do not consider myself a qualified specialist in the field of cryptography. I was dealing with cryptographic algorithms when the situation left me no other choice. Of course, it would be better if someone more knowledgeable in the matter was engaged in these works, but it so happened that I had to deal with them. In any case, I hope that my story will be interesting.

This story happened in the mid-90s. I studied at the 4th year of KAI , while working part-time at the Department of PM . I remember that I wrote something on FoxBase for one of the local "candle factory", together with several employees of the institute. The very work at the department contributed to the fact that I was constantly in sight and, at one fine moment, I was offered to participate in a new project related to the development of hardware dealing with cryptography. Of course, I agreed.

Our group consisted of a pair of fully qualified cryptologists, electronic engineers and programmers. I, as a young specialist, was engaged in HAL . Nothing special, C ++ and a bit of x86 assembly. Subsequently, we, as a group, were very successfully employed in the RCI of the Republic of Tatarstan .

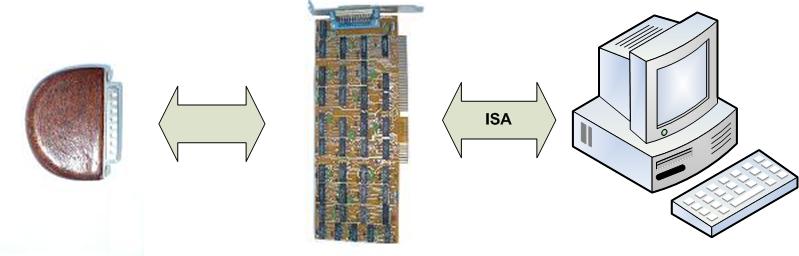

Here's what one of our products looked like (an ISA card with a removable key):

In addition to the main purpose of streaming gamma encryption , it could also be used as a high-quality pseudo-random number generator. The main feature of this device was the inability to intercept key data using software bookmarks.

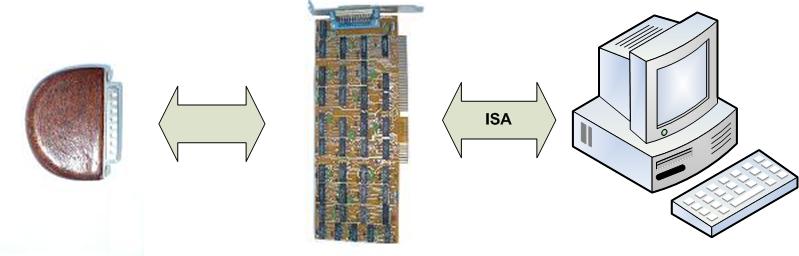

Everything was connected as follows:

Inside the key was a regular ROM-shka:

When performing encryption, from the ROM, at a given address, 16 bytes of the key were read into the device (in a row), after which, based on this key and random sync sending, the gamma used for encryption was generated. The key itself was never transferred to the PC.

I don’t remember who had the idea (it’s possible that it was for me) that if you select the key from the ROM not by row, but by byte (controlling the selection of each byte), then with all kinds of permutations, you can get much more keys. It was a really terrible idea. Quietly and imperceptibly, a hole was formed in the architecture of the hardware-software complex, which made it possible to programmatically read the contents of the entire ROM of the key.

Fortunately, this vulnerability was noticed and fixed on time, but several devices had to be redone.

In this short article, I want to warn the Reader from a frivolous attitude to issues related to cryptography. Cryptography is insidious and vulnerabilities can easily arise where you least expect them. However, I do not urge “non-professionals” to abandon the use of cryptography, similar to how this is done in this article .

Only experience and maximum attention to the task can help in detecting errors like the one described above. And if you don’t work in this direction, then experience will come from nowhere.

I will say right away that I myself do not consider myself a qualified specialist in the field of cryptography. I was dealing with cryptographic algorithms when the situation left me no other choice. Of course, it would be better if someone more knowledgeable in the matter was engaged in these works, but it so happened that I had to deal with them. In any case, I hope that my story will be interesting.

This story happened in the mid-90s. I studied at the 4th year of KAI , while working part-time at the Department of PM . I remember that I wrote something on FoxBase for one of the local "candle factory", together with several employees of the institute. The very work at the department contributed to the fact that I was constantly in sight and, at one fine moment, I was offered to participate in a new project related to the development of hardware dealing with cryptography. Of course, I agreed.

Of course, everything was not so simple.

I was given a task. They spoke in detail about the developed Device and asked to prepare its description for the upcoming exhibition. For one night at the institute (I didn’t have a computer at home then, of course), on Turbo Pascal with assembler inserts I prepared a “presentation” with EGA video effects, lots of text and pictures drawn by Line and Fill- ami. The potential employer was a little freaked out by the industriousness shown by me and the question of my employment was resolved positively.

Our group consisted of a pair of fully qualified cryptologists, electronic engineers and programmers. I, as a young specialist, was engaged in HAL . Nothing special, C ++ and a bit of x86 assembly. Subsequently, we, as a group, were very successfully employed in the RCI of the Republic of Tatarstan .

Here's what one of our products looked like (an ISA card with a removable key):

In addition to the main purpose of streaming gamma encryption , it could also be used as a high-quality pseudo-random number generator. The main feature of this device was the inability to intercept key data using software bookmarks.

Everything was connected as follows:

Inside the key was a regular ROM-shka:

When performing encryption, from the ROM, at a given address, 16 bytes of the key were read into the device (in a row), after which, based on this key and random sync sending, the gamma used for encryption was generated. The key itself was never transferred to the PC.

I don’t remember who had the idea (it’s possible that it was for me) that if you select the key from the ROM not by row, but by byte (controlling the selection of each byte), then with all kinds of permutations, you can get much more keys. It was a really terrible idea. Quietly and imperceptibly, a hole was formed in the architecture of the hardware-software complex, which made it possible to programmatically read the contents of the entire ROM of the key.

Details

Obtaining the contents of the ROM with the ability to byte-by-key download is really easy. For example, to determine the value of any byte of the address space of a key, it is enough to generate a key consisting of 16 bytes downloaded from the same address. Then, on this key, you need to encrypt any pre-selected sequence (for example, a sequence of zeros).

Since, with this method of downloading the key, there are only 256 possible options, the encryption result table can be built in advance. From this table, you can easily determine which particular byte the key consists of. In the same way, slowly but surely, you can read all the remaining contents of the hardware key.

Since, with this method of downloading the key, there are only 256 possible options, the encryption result table can be built in advance. From this table, you can easily determine which particular byte the key consists of. In the same way, slowly but surely, you can read all the remaining contents of the hardware key.

Fortunately, this vulnerability was noticed and fixed on time, but several devices had to be redone.

In this short article, I want to warn the Reader from a frivolous attitude to issues related to cryptography. Cryptography is insidious and vulnerabilities can easily arise where you least expect them. However, I do not urge “non-professionals” to abandon the use of cryptography, similar to how this is done in this article .

Only experience and maximum attention to the task can help in detecting errors like the one described above. And if you don’t work in this direction, then experience will come from nowhere.