Bluetooth First person story

We use Bluetooth to connect the headset to the phone and in many other cases. Bluetooth is built into a great variety of different gadgets, including the most unexpected ones: sneakers , dummy-teats that monitor the temperature , footballs , forks for food — even in defibrillators . Every second in the world produced 100 devices equipped with Bluetooth. It seems to many that this technology has always been. But did you know that it owes much of its birth to Intel?

Under the cat - the history of Bluetooth technology, told by its creators themselves.

Fours of the creators of Bluetooth. From left to right: Steven Nachtsheim, Simon Ellis, Jim Cardach, Johan Weber

It all started with the problem of how to provide wireless communications with rapidly expanding portable computers - laptops. The solution for short distances was protected and energy efficient technology, which we now call Bluetooth - and Intel played a significant role in its appearance.

The technology was driven by four Intel employees from the Mobile Division. Two of them after 30 years still work in the company: Johan Weber works in the Munich office as a market analyst, and Simon Ellis is the chief engineer at Santa Clara headquarters. Jim Kardach retired in 2012 after 27 years at Intel, and Stephen Nachtsheim in 2001, ending his 20-year career with the company.

In the nineties, several companies, such as Nokia, Ericsson, Intel, and Microsoft, developed effective and economical communication technologies as alternatives to wires and cables. During the GSM World Congress (now called Mobile World Congress) of 1997, Per Svensson from the Ericsson mobile unit told Weber, who was then in charge of mobile communications, about the concept of a single-chip radio module. He allowed to transmit data and voice over a distance of 10 meters, consumed little energy and cost less than $ 5.

Later they met again, they were joined by Nachtsheim and Sven Mattisson from Ericsson, the creator of the CMOS radio architecture. The result of the meeting was the decision to continue work. Already in our time, Nachtsheim recalled what had brought him to this team: he wanted to rid the laptop of dependence on a wired phone. “I still remember how I climbed in hotel rooms under the bed to find a telephone jack,” he said.

It soon became clear that in order to translate Bluetooth into life, it would be necessary to create a consortium of interested companies that would develop the standard. Jim Kardach and Simon Ellis, both from Intel's mobile division, were called to the joint working group; in addition, experts from IBM, Toshiba, Nokia and Microsoft joined it. The creation of the group was announced in May 1998. After that, the development of software and hardware, the promotion and addition of new companies to the working group began. As Weber recalls, their number grew rapidly, and on the figure of 7,000 "everyone just stopped counting." Now it has 33 thousand participants.

In the early years, Intel helped Ericsson develop and license technology. However, the company already had a wealth of experience in introducing computer standards that do not require licensing. “We understood that the availability of royalties narrows the use of technology, especially in the computer field,” says Weber. "Our task was to convince the group to abandon royalties in order to focus on improving the technology, and not get bogged down in income disputes."

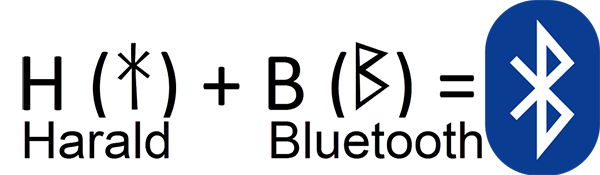

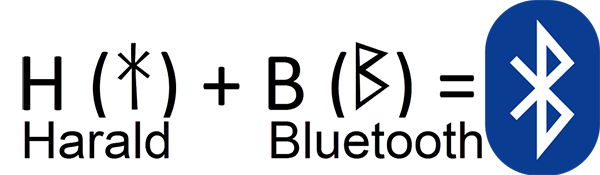

The technology logo is made from the initials Harald Bluetooth in the runic alphabet

The wireless standard was named for the Danish king of the 10th century, Harald Sinezubiy. Here's how it happened - remembers Kardach. “I first heard that name when my friend Sven Mattisson and I roamed pubs in Toronto, Canada. Discussion of issues related to the formation of a working group somehow somehow turned into the field of Scandinavian history. Sven then read the book "Long ships", where the king of the main character was Harald Sinezuby. When I returned home and bought a book on the history of Scandinavia, I found a photo of a large stone there, which Harald also found. ”

Kardach found not only the name for the technology, but also its graphic symbol . Fortunately, neither of them was protected by copyright.

“I looked at the stone and drew a sketch with a marker. The next day, I told Simon that we need to assemble a working group and call it Bluetooth, ”says Kardac. “Simon asked me to draw a cell phone and a laptop in the hands of Harald - that’s how the technology got a visual image.”

On the left is the stone of Harald Sinezubiy in Jelling. Right - drawing made for Bluetooth

“The possibility of universal use was crucial for the technology,” says Kardac. “The team had a list of 106 countries - and each had to agree on the use of Bluetooth frequency from the ISM range . Keep in mind that the EU general standards did not yet exist - we had to negotiate with each country separately. ”

Lab in Nice for Bluetooth . France agreed to use the ISM frequency on its territory and, which is also important, the French government gave the Bluetooth working group access to the test lab in Nice, the center for the study of cellular standards and their interaction.

NSA gives the go-ahead. At that time, the export of devices using encryption with a key longer than 64 bits was prohibited in the United States. “We contacted the NSA and provided them with descriptions of our encryption mechanism, asking for permission to use radio modules with 128-bit encryption,” recalls Kardac. “It turned out to be easier than we thought. The NSA studied our scheme and stated that we can export modules with 128-bit encryption without any problems. Strange, even somehow ... "

Bluetooth on the plane. “There was a concern that Bluetooth radio emission could affect the aircraft’s equipment,” says Weber. The group was required to test the effect of 2.4 GHz radiation on the aircraft. Jeff Schiffer, who worked at the Intel Mobile Group along with Kardach and Ellis, had access to one of them. “The results of the experiment were so convincing that the FAA allowed the use of Bluetooth even during takeoff and landing,” recalls Ellis. "This success also simplified the way for the introduction of Wi-Fi in airplanes."

The late Andy Grove supported the idea of wireless technology right from the start. He conducted public video conferences and reports, prompting computer manufacturers, telecom companies and telecom operators to work together to introduce wireless data transmission. “Steven Nachtsheim somehow came to his office and said that he wanted him to record a video to launch the technology, but Andy refused,” says Weber. “Stephen insisted, and Andy said that he would make only one double, only to leave behind him. I had to do two, because the first one was spoiled by a low-flying plane. ”

Grove’s video was shown in May 1998 at events in London, San Francisco and Tokyo. The following video was recorded to attract the attention of other companies to Bluetooth. “These videos have become the best way to get companies involved in our working group,” says Weber. They were used not only by Intel, Ericsson, for example, showed them at a meeting with Bill Gates.

Much water has flown under the bridge since that time. Replacing each other, 5 versions of Bluetooth came out one by one. In 2002, Bluetooth became part of the IEEE 802.15 standard, and after a very short time became the default protocol for long-distance communications. But even now, in 2018, we are still pleased that 4 Intel employees have had a hand in its success - the very ones that are depicted in the KDPV.

Under the cat - the history of Bluetooth technology, told by its creators themselves.

Fours of the creators of Bluetooth. From left to right: Steven Nachtsheim, Simon Ellis, Jim Cardach, Johan Weber

The beginning of the way

It all started with the problem of how to provide wireless communications with rapidly expanding portable computers - laptops. The solution for short distances was protected and energy efficient technology, which we now call Bluetooth - and Intel played a significant role in its appearance.

The technology was driven by four Intel employees from the Mobile Division. Two of them after 30 years still work in the company: Johan Weber works in the Munich office as a market analyst, and Simon Ellis is the chief engineer at Santa Clara headquarters. Jim Kardach retired in 2012 after 27 years at Intel, and Stephen Nachtsheim in 2001, ending his 20-year career with the company.

In the nineties, several companies, such as Nokia, Ericsson, Intel, and Microsoft, developed effective and economical communication technologies as alternatives to wires and cables. During the GSM World Congress (now called Mobile World Congress) of 1997, Per Svensson from the Ericsson mobile unit told Weber, who was then in charge of mobile communications, about the concept of a single-chip radio module. He allowed to transmit data and voice over a distance of 10 meters, consumed little energy and cost less than $ 5.

Later they met again, they were joined by Nachtsheim and Sven Mattisson from Ericsson, the creator of the CMOS radio architecture. The result of the meeting was the decision to continue work. Already in our time, Nachtsheim recalled what had brought him to this team: he wanted to rid the laptop of dependence on a wired phone. “I still remember how I climbed in hotel rooms under the bed to find a telephone jack,” he said.

Development and Licensing

It soon became clear that in order to translate Bluetooth into life, it would be necessary to create a consortium of interested companies that would develop the standard. Jim Kardach and Simon Ellis, both from Intel's mobile division, were called to the joint working group; in addition, experts from IBM, Toshiba, Nokia and Microsoft joined it. The creation of the group was announced in May 1998. After that, the development of software and hardware, the promotion and addition of new companies to the working group began. As Weber recalls, their number grew rapidly, and on the figure of 7,000 "everyone just stopped counting." Now it has 33 thousand participants.

In the early years, Intel helped Ericsson develop and license technology. However, the company already had a wealth of experience in introducing computer standards that do not require licensing. “We understood that the availability of royalties narrows the use of technology, especially in the computer field,” says Weber. "Our task was to convince the group to abandon royalties in order to focus on improving the technology, and not get bogged down in income disputes."

The technology logo is made from the initials Harald Bluetooth in the runic alphabet

Title history

The wireless standard was named for the Danish king of the 10th century, Harald Sinezubiy. Here's how it happened - remembers Kardach. “I first heard that name when my friend Sven Mattisson and I roamed pubs in Toronto, Canada. Discussion of issues related to the formation of a working group somehow somehow turned into the field of Scandinavian history. Sven then read the book "Long ships", where the king of the main character was Harald Sinezuby. When I returned home and bought a book on the history of Scandinavia, I found a photo of a large stone there, which Harald also found. ”

Kardach found not only the name for the technology, but also its graphic symbol . Fortunately, neither of them was protected by copyright.

“I looked at the stone and drew a sketch with a marker. The next day, I told Simon that we need to assemble a working group and call it Bluetooth, ”says Kardac. “Simon asked me to draw a cell phone and a laptop in the hands of Harald - that’s how the technology got a visual image.”

On the left is the stone of Harald Sinezubiy in Jelling. Right - drawing made for Bluetooth

Implementation difficulties

“The possibility of universal use was crucial for the technology,” says Kardac. “The team had a list of 106 countries - and each had to agree on the use of Bluetooth frequency from the ISM range . Keep in mind that the EU general standards did not yet exist - we had to negotiate with each country separately. ”

Lab in Nice for Bluetooth . France agreed to use the ISM frequency on its territory and, which is also important, the French government gave the Bluetooth working group access to the test lab in Nice, the center for the study of cellular standards and their interaction.

NSA gives the go-ahead. At that time, the export of devices using encryption with a key longer than 64 bits was prohibited in the United States. “We contacted the NSA and provided them with descriptions of our encryption mechanism, asking for permission to use radio modules with 128-bit encryption,” recalls Kardac. “It turned out to be easier than we thought. The NSA studied our scheme and stated that we can export modules with 128-bit encryption without any problems. Strange, even somehow ... "

Bluetooth on the plane. “There was a concern that Bluetooth radio emission could affect the aircraft’s equipment,” says Weber. The group was required to test the effect of 2.4 GHz radiation on the aircraft. Jeff Schiffer, who worked at the Intel Mobile Group along with Kardach and Ellis, had access to one of them. “The results of the experiment were so convincing that the FAA allowed the use of Bluetooth even during takeoff and landing,” recalls Ellis. "This success also simplified the way for the introduction of Wi-Fi in airplanes."

Andy Grove Video

The late Andy Grove supported the idea of wireless technology right from the start. He conducted public video conferences and reports, prompting computer manufacturers, telecom companies and telecom operators to work together to introduce wireless data transmission. “Steven Nachtsheim somehow came to his office and said that he wanted him to record a video to launch the technology, but Andy refused,” says Weber. “Stephen insisted, and Andy said that he would make only one double, only to leave behind him. I had to do two, because the first one was spoiled by a low-flying plane. ”

Grove’s video was shown in May 1998 at events in London, San Francisco and Tokyo. The following video was recorded to attract the attention of other companies to Bluetooth. “These videos have become the best way to get companies involved in our working group,” says Weber. They were used not only by Intel, Ericsson, for example, showed them at a meeting with Bill Gates.

* * *

Much water has flown under the bridge since that time. Replacing each other, 5 versions of Bluetooth came out one by one. In 2002, Bluetooth became part of the IEEE 802.15 standard, and after a very short time became the default protocol for long-distance communications. But even now, in 2018, we are still pleased that 4 Intel employees have had a hand in its success - the very ones that are depicted in the KDPV.