The course of lectures "Startup". Peter Thiel. Stanford 2012. Lesson 4

- Tutorial

This spring, Peter Thiel ( by Peter Thiel ), one of the founders of PayPal and the first investor FaceBook, held a course at Stanford - "Start-up". Before starting, Thiel said: “If I do my job correctly, this will be the last subject that you will have to study.”

One of the students of the lecture recorded and posted the transcript . In this habratopika, I am translating the fourth lesson. Editor of Astropilot .

Lesson 1: Challenging the Future

Lesson 2: Again, Like in 1999?

Session 3: Value Systems

Session 4: The Last Step Advantage

Session 5: Mafia Mechanics

Session 6: The Law of Thiel

Session 7: Follow the Money

Session 8: Presentation of an Idea (Pitch)

Lesson 9: Everything Is Ready, But Will They Come?

Session 10: After Web 2.0

Session 11: Secrets

Session 12: War and Peace

Session 13: You Are Not a Lottery Ticket

Session 14: Ecology as a Worldview

Session 15: Back to the Future

Session 16: Understanding Yourself

Session 17: Deep Thoughts

Session 18: Founder - Victim or God.

Occupation 19: Stagnation or Singularity?

Lesson 4: The Last Turn Advantage

I. Refusal of competition

It is generally believed that capitalism and perfect competition are synonyms. There are no monopolies. Firms compete, and competition eats up profits. Curiously, it is better to consider capitalism and perfect competition as two opposites. Capitalism is, first of all, the accumulation of capital, while in a world with perfect competition it is absolutely impossible to make money. Why people strive to present capitalism and perfect competition as interchangeable things is an interesting issue that requires comprehensive consideration.

The first thing to admit is that our positive attitude towards competition has deep roots. Competition is something typically American. She tempers character. She teaches us a lot. Competition pervades the entire field of education. Sometimes extremely high competition lays the foundation for future success, already devoid of competition. For example, to enter the medical faculty you need to withstand very high competition, but as a result you become a highly paid specialist.

Of course, there are cases when perfect competition is really good. Not all businesses are created for the sake of money; there are people who can work without making much profit, earning exactly as much as they need for a living. But as soon as a person takes care of making money, he begins to be skeptical of perfect competition. In areas such as sports and politics, high competition was inherent in the beginning. It is easier to create a successful business than to run the 100-meter faster than anyone or to be elected as president.

It can upset people that competition is not always good. It is necessary to explain what I mean. In a sense, competition is really useful. It allows you to make learning and education better. Sometimes letters and recommendations really reflect a high degree of achievement, but the concern is that the pursuit of them often turns into a habit. Too often we forget about the goal of competition, in the end people just learn to compete always and in everything. This is a disservice, since the best you can do is stop competing, become a monopoly and enjoy success.

I will illustrate this with one story from the life of a law school. For graduation, Stanford Law School students (SLS - Standford Law School) and other elite universities earn awards and recommendations for the next ten years. The most prestigious thing is to get the post of Secretary of the Supreme Court. After graduating from SLS in the 92nd, having worked for a year in the 11th arrondissement, I was among a small handful of clerks who got to interview two Judges from the Supreme Court. The coveted position was at arm's length. I was one step away from winning this last competition. It only remained to hear “yes” and life would be arranged. But the dream did not come true.

A few years later, after I created and sold PayPal, I met one of my old SLS friends. The first thing a friend asked was: “Well, are you glad you didn’t get a job in the Supreme Court then?” It's funny, because once it seemed that getting this job is very important, but there are many reasons why victory in this last competition is not worth it in the end. Probably, in the future this would threaten even more insane competition. And there would be no paypal. This is expressed succinctly in the phrase about Rhodes Scholars: "In the past, they all had a great future."

This does not mean that positions, scholarships and awards are often not a sign of high achievement. We must give them their due. Just very often in a competitive race, we confuse what is valuable with what is difficult to achieve. Fierce competition pushes our foreheads, making victory difficult. Intensity of competition replaces value, but value is a completely different concept. In extreme form, we often compete for the sake of competition. Henry Kissinger's anti-academic statement quite accurately illustrates the relationship between achievement difficulty and value: in the scientific world, battles are fiercer the lower the stakes.

This seems to be true, but it seems a little strange. If the stakes are so low, why do people keep fighting hard instead of doing something else? Question for thought. Maybe these people could not figure out what was valuable, and they knew only one way - the way of struggle. Or they succumbed to the romantic spell of competition. In any case, it is important to understand at what point it makes sense to step aside and turn life toward a monopoly.

Let's look at the high schools, which for students of Stanford and the like were not an example of perfect competition. It was an inadequate battle for the means used: machine guns against bows and arrows. Without a doubt, just fun for the best students. Further the university and competition intensifies. In graduate school is even tougher. The worst situation is in the professional world: at every step, people compete with each other to move forward. In general, this is a rather insidious question. With mother's milk, we absorbed that strong, perfect competition is changing the world for the better. But in many ways deep competition is hidden in competition.

One of the challenges of fierce competition is that it demoralizes. The best graduates of schools, getting into elite universities, quickly become convinced that the bar has risen. But instead of questioning the existence of this bar itself, they tend to accept the challenge and participate in the race. You have to pay for it. In various universities, this problem is solved in different ways. At Princeton, the solution is a huge amount of alcohol to help smooth out the corners a bit. Yale offers a painkiller in the form of eccentricity and encouraging students to engage in esoteric sciences. Harvard went the farthest; he sent students straight to the center of the cyclone, forcing them to compete even more intensely. In fact, all this leads only to the fact that you will be repeatedly beaten by all these superhumans. Is this normal?

Of all the elite universities, Stanford is farthest from perfect competition. Maybe this is an accident, or maybe it was intended. Probably, the geographical position contributed to this, the east coast never showed much attention to us, and we did not remain in debt. The diversity of the university’s specialties also had its effect: a strong technical school, a strong humanitarian and even the strongest sports school in the country. There is competition here, but more in jest than in earnest. Consider, for example, the rivalry of Stanford and Berkeley. It is, to a greater extent, also asymmetric. In football, Stanford usually wins. But let's take for example something really important, for example, the creation of high-tech companies. If you ask the question: “Graduates of which of the two universities founded the most valuable company?” Obviously, that over the past 40 years, Stanford will win with a score of 40: 0. This is monopoly capitalism, terribly far from the world of perfect competition.

An excellent illustration of competition is war. Everyone just kills everyone. There is always a rational explanation for war. Previously, it was often romanticized, now less often. This has its own logic: if you accept that life is really war, then most of your life you need to either fight or prepare for it. This is the way of thinking that is being grafted at Harvard.

But what if life is not war, but something more? Maybe sometime you just need to step aside? Maybe it’s better to sheathe the sword, look around and choose some other target? Maybe “life is war” is an unreasonable lie that they inspire us, and the competition is not so good?

II What people are lying about

One of the negative conclusions from all this is that life is really war. It is difficult to determine which part of life is perfect competition and which monopoly. You need to start by evaluating the various claims that life is war. To do this, we must strictly sweep away the lies and distortions of meaning. Let's look at the reasons why people can distort the truth about monopoly and competition in the technology world.

A. Bypass the Ministry of Justice

One of the problems is that if you have a monopoly, you probably don't want to talk about it. Antitrust law has its own subtleties and can easily be misleading. And, generally speaking, a leader who boasts that he controls a monopoly is an invitation to audit, increased attention and excessive criticism. There is no point in doing so. Due to serious potential political issues, there is a strong positive incentive to distort the truth. You do not just need to say that you are a monopoly; on the contrary, you need to shout from all the bells that this is not so, even if it is indeed so.

The world of perfect competition is also not entirely free from distortions and lies. As elsewhere, one of the truths in this world is that companies need investment. But another truth is that investors should not invest in such companies, since none of them can and will not make a profit. When two truths collide, there is a reason for distorting one of them.

So, monopolies pretend that they are not monopolies and vice versa. On the scale between perfect competition and monopoly, the range that most companies fall into is very narrow due to what these companies say about themselves. We see only small differences between them. Since people have very strong reasons for lying about the convergence of opposites, the reality of monopoly and competition in the commodity business is probably more polar than it seems to us.

B. Lies about the markets

People also tend to tell lies about markets. Really large markets are prone to high competition. No one wants to be a small fish in a big pond. Everyone wants to be the best in their class. So, if your business is in a competitive situation, you can well fool yourself into thinking that your market is much smaller than it really is.

Suppose you are going to open a restaurant in Palo Alto, which will offer visitors only dishes of English cuisine. There will be only one such restaurant in Palo Alto. “No one else does this,” you say, “We are one of a kind.” But is it? What market do you work in? In the British market? Or is it a restaurant market in general? You need to consider only the Palo Alto market, or you must also consider people traveling to / from Menlo Park and Mountain View to eat. These are complex questions, but an even bigger problem is the tendency not to ask them at all. Most likely, in your reasoning, you underestimate the market. If a rude investor reminded you that 90% of restaurants burn out in the first 2 years, you would come up with a story about what is your difference. You would take the time to convince people that you are the only player standing here, instead of seriously considering whether this is true. You have to wonder if there are people in Palo Alto who prefer only English cuisine. In this example, these are the only people you can motivate to pay as much as you want. And, quite possibly, such people simply do not exist.

In 2001, some PayPal employees dined at Mountain View on Castro Street. There, as now, there were many eateries for every taste. If you wanted Indian, Thai, Vietnamese, American or any other cuisine, it was easy to find several restaurants to choose from. Even if you decided on the type, you could choose further. Indian restaurants, for example, were divided into South and North Indian, inexpensive and elite. Castro Street was saturated with competition. PayPal, by contrast, was the only payment processing company in the world at that time. There were fewer employees at PayPal than at Mountain View restaurants, however, in terms of capital, PayPal was much more valuable than all of these restaurants combined. Creating a new South Indian restaurant on Castro Street was (and is now) a pretty difficult way to make money. This is a large competitive market, but when you focus on one or two differentiating factors, it’s easy to convince yourself that it’s not.

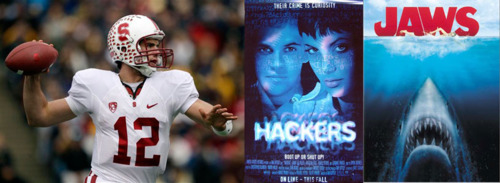

Movie advertising uses the same principle. Most videos claim that the film will be truly unique. This new film, investors say, will combine certain elements in a completely new way. And that may even be true. Suppose we plan to use the star of Andrew Luck in the film, a cross between Hackers and Jaws. You get something like this: the American football star joins an elite group of hackers to catch the shark that killed his friend. Definitely no one has done this before. We had sports stars, “Hackers”, “Jaws”, but there was never what is indicated by their intersection on the Venn diagram. The whole question is whether this intersection will bring any benefits or not.

The conclusion is that it is very important to understand how this all works. Non-monopolies always downplay the market in which they operate, while monopolies insist that their market is huge. Using logical operators, non-monopolies use the intersection of markets: English cuisine ∩ restaurants ∩ Palo Alto, football star ∩ hackers ∩ sharks. Monopolies, on the other hand, use unification to draw us a story about a tiny fish in a large pond. They kind of say: “No, no, we are not the monopoly that the government is looking for.”

C. Lies about market shares

There are various ways to split markets. Some are better, some are worse. It is crucial to ask about the true nature of your market, and get as close to the answer as possible. If you are creating an application for mobile devices, you need to decide whether your market is the entire market for iPhone applications (in which there are several hundred thousand other applications), or there is a way to create your own dedicated small market. This process must be approached as impartially as possible, not succumbing to outside influence.

Let's look at the search engine market. The answer to the question of whether Google is a monopoly or not depends on which market the company operates in. If you say that Google is a search engine, then it owns 66.4% of this market. Microsoft and Yahoo own 15.3% and 13.8% respectively. Using the Herfindahl-Hirschman index, we conclude that Google is a monopoly, since the 66% index is much more than 0.25.

But suppose Google is an advertising agency, not a search engine. It changes everything. The search advertising market in the USA is estimated at $ 16 billion. The online advertising market in the USA is $ 31 billion. The general advertising market in the USA is $ 144 billion. The global advertising market is $ 412 billion. Even if Google dominates the $ 16 billion search engine market in the USA, in the context of the global advertising market, this is less than 4%. Now Google is much less like a monopoly, and more like a small player in a very competitive environment.

You can also say that Google is a technology company. Yes, Google is engaged in search and advertising, but Google also produces cars, computer-controlled, engaged in television. Google Plus is trying to compete with Facebook. Google also challenges the entire telephone industry with its Android phones. The consumer high-tech market is valued at $ 946 billion, so if we consider Google a technology company, we should consider it in a completely different context.

Not surprisingly, Google is positioning itself that way. Monopolists and large companies that care about public opinion tell everyone a “unifying” story. Defining your market as the union of all its main and peripheral markets, and imagining yourself as a small fish in a large pond. Their stories are very reminiscent of Eric Schmidt’s quote:

"The Internet is an incredibly highly competitive environment, every day new forms of access to information arise and begin to be used here." The

subtext is this: we must run as hard as we can to at least stay in one place. We don’t so big. We can be defeated and destroyed at any time. In this sense, we are no different from the pizzeria in the center of Palo Alto.

D. Cash and competition

A very important indicator is the amount of money in the accounts of the company. Apple has $ 98 billion (and grows by about $ 30 billion every year), Microsoft has $ 52 billion, Google has $ 45 billion, Amazon has $ 10 billion. In a world of perfect competition, you have to reinvest all your money in order to keep your position. If you are able to grow by $ 30 billion per year - there is doubt about the competitiveness of the environment. Consider the gross margin - the difference between revenue from sales of products and variable costs. Apple has a gross margin of 40%, Google has 65%, Microsoft has about 75%, Amazon has 14%. But a profit of even 14 cents per dollar is gigantic, because for retail, the norm is something around 2%.

With perfect competition, marginal revenues are equal to marginal expenses. Hence the understanding that the high margin of large companies involves a combination of two or more businesses: a central monopoly business (for Google this is a search engine) and a group of various additional business projects (computer-controlled cars, television, etc.). The amount of cash is growing because managing the monopoly part does not involve high costs, and it does not make sense to upload all the money to third-party projects. In a competitive world, sustainability would require far greater investment in third-party projects. There is no strict need for this in the world of monopoly, and large investments in third-party projects are more of a political decision. Amazon, for example, reinvests approximately 3% of its profits. Im of course

III. How to capture the market

In order to take over the market, a company must use some combination of brand, scale advantages, network effects and proprietary technologies. Among these elements, brand is the most difficult to define. You can consider the brand as a keyword. If you hear "brand", the conversation is about monopoly. But to understand in more detail is more difficult. Whatever the brand is, it means that people do not find the product easy to replace, and therefore willing to pay more. Take, for example, Pepsi and Cola. Most people have a fairly steady preference for one of these drinks. Both companies generate huge cash flows, because the customers, it turns out, cares. They buy one of these brands. A brand is a rather cunning concept for investors; it is difficult to identify and take it into account in advance.

The benefits of scale, network effects and proprietary technologies are much easier to understand. The benefits of scale play a role where there are high fixed and low variable costs. Amazon has major economies of scale in the online sales world, and Wal-Mart has significant retail benefits. The more they grow, the more efficient they are. There are many different network effects, but the gist of them is that certain product properties lock customers around a particular business. The situation is similar with patented technologies, there are many ways to secure the right to technology, but the essence is the same everywhere - while others are standing, you are developing.

Apple is probably the largest technology monopoly to date - it has all of these elements. By creating both software and hardware, they fully own the value chain. Thousands of people working at Foxconn create economies of scale. Countless developers creating the Apple platform and millions of loyal customers interacting with the Apple ecosystem create network effects that keep customers within the brand. In addition, the Apple brand is not only a combination of all these elements, but also something else, quite elusive. If another company made a similar product, they would have to sell cheaper than Apple. Even without taking into account other advantages, the Apple brand allows for better monetization.

IV. Creating your own market

To create a truly valuable technology company, you need to complete three steps. First, you need to find or create a new market. Secondly, monopolize this market. And thirdly, it will be necessary to understand how to extend the monopoly in time.

A. Choosing the right market

The principle of the golden mean is the key to choosing an initial market; the market should be neither too small nor too large. It should be just right. Too small a market means a lack of customers, which is a problem. This is exactly what happened with PayPal's original idea of transferring money between Palm Pilot devices. Nobody did it anymore - it was good, but in reality nobody needed it - but it was already bad.

Too large markets are bad for all of the previously listed reasons; they are difficult to manage, and they are too highly competitive to make money there.

Finding the right market is not just an exercise for the mind. We are no longer talking about choosing the right words to convince investors or self-deception. This has nothing to do with the stories of “intersection” or “unification”. All you really need is to find out the objective truth about the market.

B. Monopoly and growth

If you have not completely decided on the market and how to scale it, you have not yet found the right market. A scaling plan is critical. A classic example is Edison Hoover - Bell's telephone company. Alexander Graham Bell invented the phone, and with it the new market. Initially, this market was small; only a tiny group of people were involved in it. In this small market at an early stage of development, it was very easy to remain the only one. Then they grew up, and everyone continued to grow. The market has become stable. Network effects began to appear. It quickly became almost impossible to enter this market from the side.

Thus, the best businesses are those that have a clear idea of the future. The stories may differ, but the scheme is always about the same: find a small target market, become the best on it, immediately capture adjacent markets, expand the range of what you are doing, capture more and more. The larger the scale you achieve, the more network effects, technology, scale benefits and the brand will make it harder for others to enter your market. This is the recipe for creating valuable businesses.

Probably, in the history of each technology company, this template in one form or another played a role. Of course, the development of an absolutely accurate plan for the development of a company requires, obviously, an understanding of the future of the whole world, which probably will not happen. But this does not mean that you do not need to try. The more you think about it, the better your plan will be, and your chances of creating a truly valuable company will be higher.

C. Some examples

At the time of launch, Amazon was very small. It was just an online bookstore. Except that it was probably the best bookstore in the world, since he had ALL books in his catalog - and this is a non-trivial thing, you must admit. But the scale was very manageable. What is amazing is how they, from a bookstore, could step by step turn into the largest online supermarket in the world. This was part of the original vision. The name Amazon (Amazon River, approx. Translator) is simply brilliant; The incredible diversity of life in the Amazon reflects the original purpose of cataloging every book in the world. The elasticity of this name allowed them to grow smoothly, without breaks. On a different scale, the diversity of the Amazon can be interpreted as the diversity of all things in the world.

eBay also started small. The idea was to create a platform and keep abreast. The first opportunity was the popularity of Pez sweets with a dispensing toy. eBay was the only place Pez collectors could get it. Next up were Beanie Baby soft toys. Soon, eBay became the only place in the world where you could quickly get any kind of Beanie Baby, whatever you want. Creating a working platform for auctions is the creation of a natural monopoly. The site is full of buyers and sellers. If you are a buyer, you naturally go where there are many sellers. If you are a seller, you go where the buyers are. This is why most companies trade only on one exchange; in order to create liquidity, all buyers and sellers must be concentrated in the same place.

In 2004, a problem arose on eBay: it became apparent that the auction model could not be extended to all. Everything worked well, as a marketplace for unique products, such as coins or stamps, for which there is high demand but low supply. For the sale of ordinary goods traded by companies such as Amazon, Overstock and Buy.com, this model was not very successful. eBay is still a big monopolistic business. It is simply smaller than people expected from it in 2004.

LinkedIn has 61 million users in the United States and 150 million worldwide. The idea was that it was supposed to be a network for everyone. In reality, now it is mostly used for hiring employees. Someone suggested using this in the short and long term: in the short term for companies, most of whose employees join LinkedIn to post a resume and find a job, and in the long term for companies that are not actively showing themselves on LinkedIn. An important question about LinkedIn is whether the business contact network is the same as the social network. LinkedIn's position is that there are fundamental differences. If so, then they have captured this market for a long time.

Twitter is a classic startup example with a small niche product. The idea is simple - anyone can become a microbroadcast. This works even if only a few people are involved. But, with scaling, it turns into a new media. The big question regarding Twitter is whether it can ever make money. It is very difficult to answer. But if you ask a question about the future in terms of technology - do you have a technological advantage? Are you protected? Can people repeat this? Here, the service seems to have nothing to fear. If the Twitter market is a market for sending messages up to 140 characters long, it will be extremely difficult to repeat it. Of course, you can copy it, but not repeat it. In fact, it’s almost impossible to imagine such a technological future, in which anyone can compete with Twitter. Increase the number of characters to 141 and compatibility with SMS will be lost. Reduce the number of characters to 139, and you just lose one character. Thus, while the question of monetization is open, Twitter has a margin of safety that is hard to crush.

Zynga is another interesting case. Mark Pincus wisely said: "The absence of a clear goal at the very beginning leads to death through a thousand small compromises." Zynga started well from the start. They started by developing social games like Farmville. They aggressively copied everything that worked, grew, figured out how to monetize these games - how to get enough users paying for gaming privileges - and did it better than anyone else. Their success with monetization led to a viral effect and allowed them to quickly get even more customers.

The question about Zynga is how stable are they? Is it a creative or not a creative business? Zynga insists that they are not a creative or design company. If that were the case, developing new successful games would be a difficult task, and Zynga would be a bit of a game version of a Hollywood studio, the success of which can vary significantly from season to season. Instead, Zynga serves himself up with some kind of hot psychometric sauce. . They would be better off if, with the help of any psychological or mathematical laws, they could provide themselves with a long-term monopoly advantage. It’s as if Zynga wants (or maybe “would like”) to say, crookedly: “we know how to convince people to buy more, and therefore we are a stable monopoly”.

Groupon also started small and aggressively growing. The question about Groupon is what their relevant market is, and how they can capture it. Groupon insists they are a brand. It is they who penetrate into all these cities, and people turn to them, and not to anyone else. Opponents of Groupon say they lack proprietary technologies and network effects. If their brand is not as strong as they claim, in the long run they will have to face many challenges.

All these companies are not alike, but the scheme is about the same: start in a small, well-defined market, expand, and always control your stability and the possibility of further advancement. The best way to overwhelm everything is to do the opposite - starting big and decreasing. Pets.com, Webvan and Komozo.com made this mistake. There are many models leading to failure, but in the first place is still a biased assessment of the market and its conditions. You will not succeed simply by believing in your own idea of the market if it is different from reality. We do not take luck into account.

V. White spots in technology

There are always unoccupied niches in existing markets. Instead of creating a new market, you can always “destroy” an existing industry. But the significance of the “destruction” stories of technology is probably exaggerated. Destroyers often fail. Schoolchildren-hooligans called to the director. Take Napster, for example. Napster was a destructive company, perhaps even too destructive. They violated too many rules, and people simply were not ready for this. Even the name itself, Napster (the words are played out: nap - to steal, kidnap, gangster - gangster; napster can be translated as "thief", approx. Translator), it seems hooligan. And what can you steal? Music and children, damn it. In short, instead of “destroying” something, it is better to find white spots in technologies and tackle them.

But where are these white spots? How to approach them, on which side should we think about them? There is one starting point that can help. Imagine a world covered by ponds, lakes and oceans. You are in a boat, somewhere in the middle of the water. Very foggy, and it is not clear how far the shore is. You do not understand where you are: in a pond, in a lake or in the ocean.

If you are in a pond, you can expect that in about an hour you will reach the shore. If the day has passed, it means that you are either in the lake or in the ocean. If a year has passed, you cross the ocean. The longer you travel, the longer it seems you still have to travel. In truth, with time you are getting closer and closer to the other side, but the fact that time passes means that you still have to go and go.

Does the same thing happen with technology? Where are the places where you can continue to move? White spots are promising areas, but at the same time very uncertain. One can imagine a high-tech market where nothing happened for a long time, then suddenly everything started to boil, and stopped again. White spots in technology are temporary, unlike geographic unexplored areas. They manifest when something happens.

Let's look at the automotive industry. Trying to create a car company in the 19th century was a bad idea. It was too early. But creating such a company now is extremely late. There are now about 300 car manufacturers, some of which still exist, were created in the 20th century. The time for founding a car manufacturing company is the time when automotive technology was created, not earlier and not later.

You need to ask yourself whether it is right to enter the hi-tech industry at the very beginning, as common sense suggests. Perhaps the best time to enter is much later. You cannot be late, because you still need free space in order to do something. You need to enter the segment at the very moment when you can make the last big breakthrough, after which the bridges will be already built, and you will get a long-term advantage. You need to choose the right time, invest in technology while it's cheap, succeed, and then sell the company at its peak.

Microsoft is probably the latest operating system company. She was one of the very first, but there is a feeling that she will be the last too. Google is the latest search company; they have made significant improvements in the search with the transition to an algorithmic approach, it is almost impossible to improve. What about bioinformatics? A lot of what seems to be happening here. But it’s hard to say whether it’s too early to invest there. The area seems very promising, but now it’s hard to say what will happen to it in 15-20 years. If your goal is to create a company that will still exist in 2020, you need to avoid areas where things change too quickly. It is unlikely that you want to be like innovative, but profitable hard drive companies from the 80s.

Some markets are similar to the automotive industry. Would you like to create a lithium battery and battery company? Probably not. The times for this, apparently, have already passed. Innovation may be too slow, and technology may already be established by now.

Sometimes markets that seem already fully established are not. Take, for example, the aerospace industry. SpaceX believes that the cost of launching spacecraft can be reduced by 70-90%. That would be incredibly valuable. If nothing happened in a certain area for many years, and then you came and spectacularly improved something really important, everything says that no one else can repeat it.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is probably an underrated area. People have already somehow burned out about this topic, probably because for many decades there have been certain exaggerated expectations. Very few really believe that AI already exists or will be implemented in the near future at the current level of development. But progress is relentless. The performance of AI in chess is constantly increasing. After 4-5 years, computers are likely to beat a person in Go. AI is probably well regarded as one of the white spots of technology. The problem is that no one knows exactly what the long-term prospects are.

Worth mentioning is the mobile Internet. The question is whether there is a "gold rush" in mobile technology. And the important next question, if you still have a gold rush, who better to be, a gold digger, or a guy selling shovels for gold diggers? Google and Apple themselves are trading shovels. Maybe there’s not much gold left. The concern is that the market is too big. A lot of competing companies. As we have discussed, there are various rhetorical tricks that can be used to reduce the size of the market and make any company seem more unique. Maybe you can create a mobile company that will seize a valuable niche. Maybe you can find some gold. But all this should be skeptical.

VI. White spots technology and people

One way to determine if you have found a promising white spot for development is to answer the question: “For what reason should the twentieth employee join your company?” If you have a good answer to this question, you are on the right track. Otherwise, no. The problem is that the question sounds deceptively simple.

What does a “good” answer consist of? First of all, let's put the question in a specific context. It must be admitted that there is indirect competition for good employees with companies such as Google. Thus, a more mundane version of the question is: “For what reason does the twentieth engineer want to join your company, when he could go work for Google, getting more money and prestige?”

The correct answer is that you are creating a kind of monopolistic business. Business at an early stage of development directly depends on the qualifications of the people participating in it. To attract the best people, you need a convincing monopoly story. Because you are competing with Google for talents, you must understand that Google is a great monopoly business. You do not need to compete with them in the search engine market, but from the point of view of hiring employees, you cannot compete with a large monopoly business until you have a strong history in which you yourself become a large monopoly business.

This raises the question that we will discuss next week: what kind of people do you need to take with you when you decide to research and fill in the blank spots in technology?

From the translator:

I ask for translation errors and spelling to send to the LAN. I also remind you that this text is a translation, its content is copyright, and the author's opinion may not coincide with mine.

Editor of Astropilot . Thanks to her.