Mini empires

- Transfer

What does a strategy game look like if we look only at the mini-map? Recently, I decided to explore this idea, returning to the classic Age of Empires II .

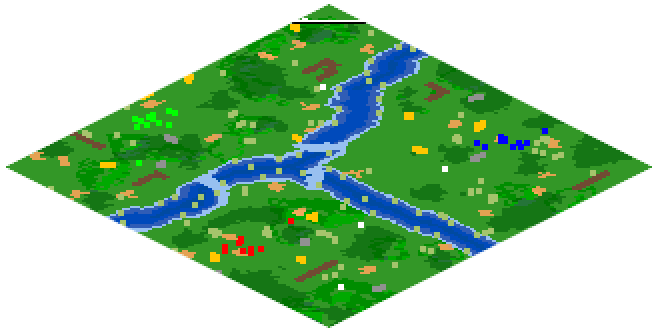

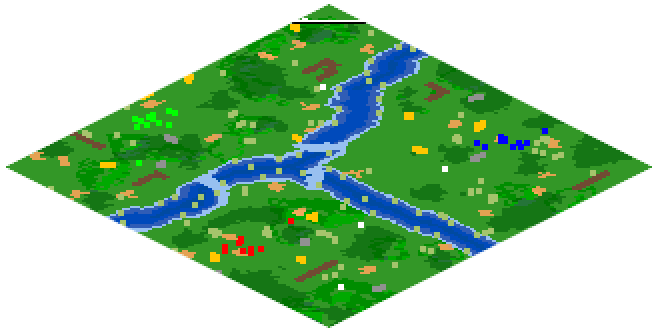

I started by studying a match with three AI players on a medium sized map. Here is the initial state:

If the “First Player to Prepare” and taught me something, it is that it is absolutely normal to hold on to my childhood forever.

By taking screenshots of a mini-map every few seconds, we can create a time-lapse of the game. Each frame in the video shown below represents two seconds of real time. With a frequency of 24 frames per second, the two-hour game takes a much more comfortable two and a half minutes:

Here is the same match with the cleaned background. Reminds me of bacteria fighting in a petri dish:

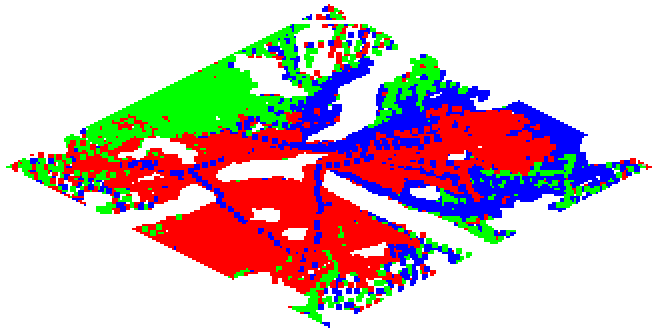

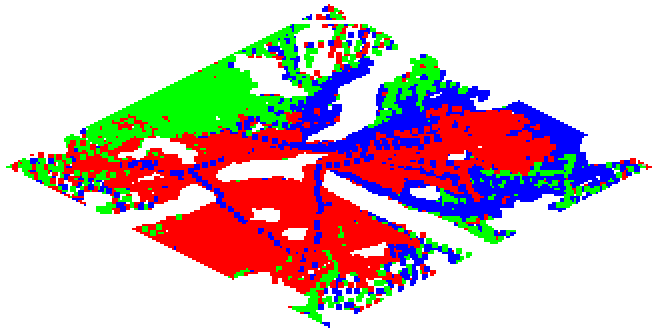

When frames are superimposed on each other, this pattern is obtained:

Averaged blending of all frames shows standard routes on the map:

To better show the movement and actions, I also tried to consider only the visual differences between each of the frames:

And here is a visual representation of the coverage with each color:

Color cover card. As in other examples, it plays at a speed of 2x.

Combining the frames from this video into one image, moving from left to right, we get the following:

Handsomely.

Watching the timelapse of AI behavior is fascinating, so I decided to capture several other matches to see what they looked like. Unless otherwise stated, all of them use the following parameters:

Here is the previous match and three replays. Despite the same starting conditions, each develops in its own way:

In these time-lapses, we begin to notice patterns of AI behavior. In many ways, they are quite ridiculous (at least on a standard difficulty) - the AI attacks, sending a chain of units to the target or retreating right after it has amassed an army on the border with the defenseless city of the enemy.

Matches for three players are especially interesting due to their dynamics. Sometimes two players unite against the third, sometimes the “royal battle” begins in the center of the map, and sometimes the third player conducts a covert attack, while the first and second players fight each other (the AI is not smart enough to actually plan all these maneuvers; they just appear naturally).

The lack of this dynamic makes two-player matches shorter and usually less interesting. Here are some examples:

The picture improves again when we go to four-player matches. In such matches, the fourth player is often destroyed in the early stages, which again leads to a match for three players.

I recorded most of these matches, leaving the game for the night. Most lasted one to two hours, but some have stabilized in stalemate situations. For example, in the four-player match shown below, everything starts very exciting, until the AI seems to be at a dead end. Having spent all the land resources, blue and yellow just surrendered, while red carelessly continues to endlessly fish.

Matches for eight players are more chaotic. In such matches, there are four teams of two players:

Golden fever

Fortress

In one of the games there were almost no fights:

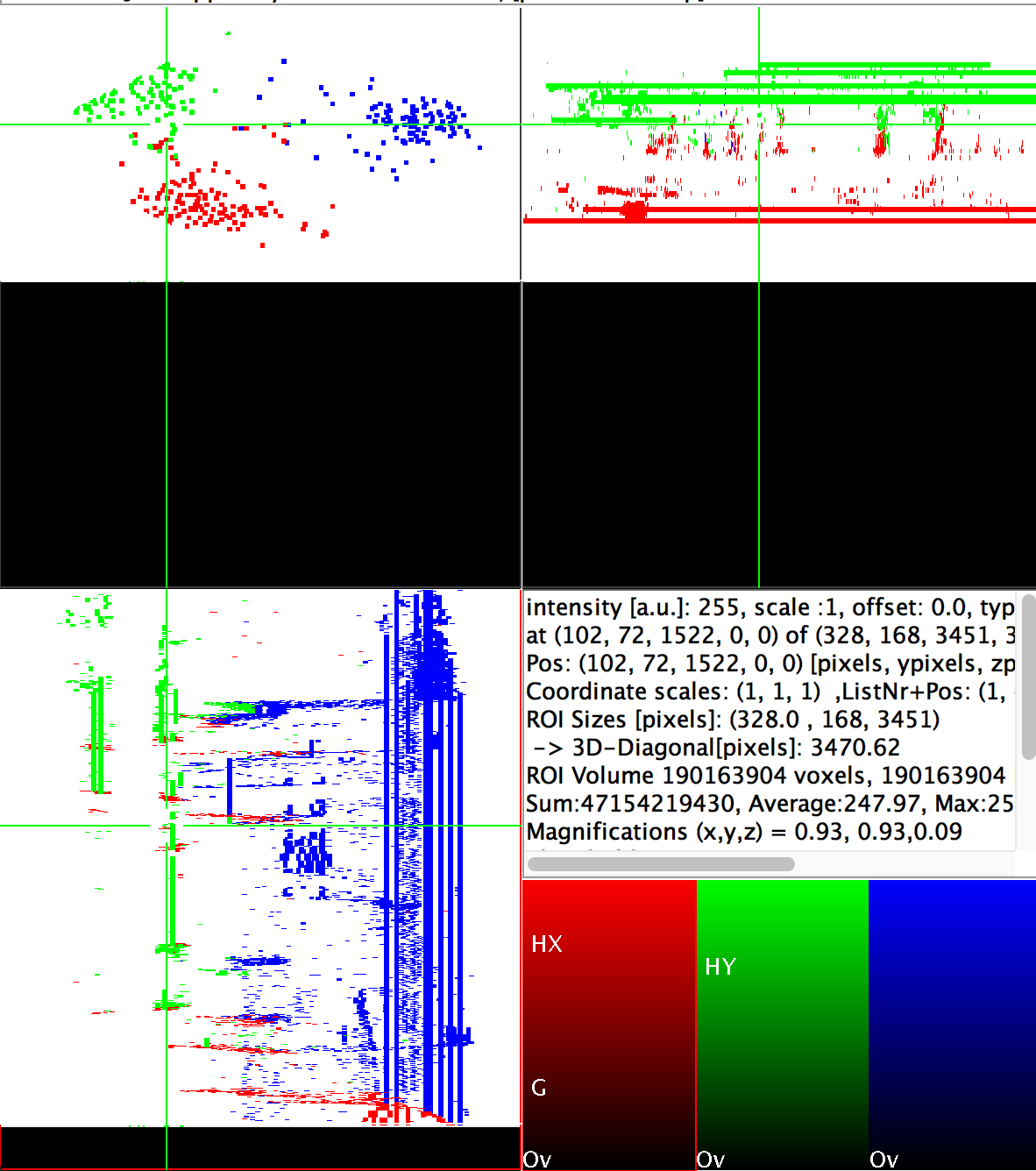

Of course, there are many other ways to study the data, except for the timelapse. One of the most interesting is the projection of 2D slices of a mini-map onto a three-dimensional volume. For this analysis, I used ImageJ .

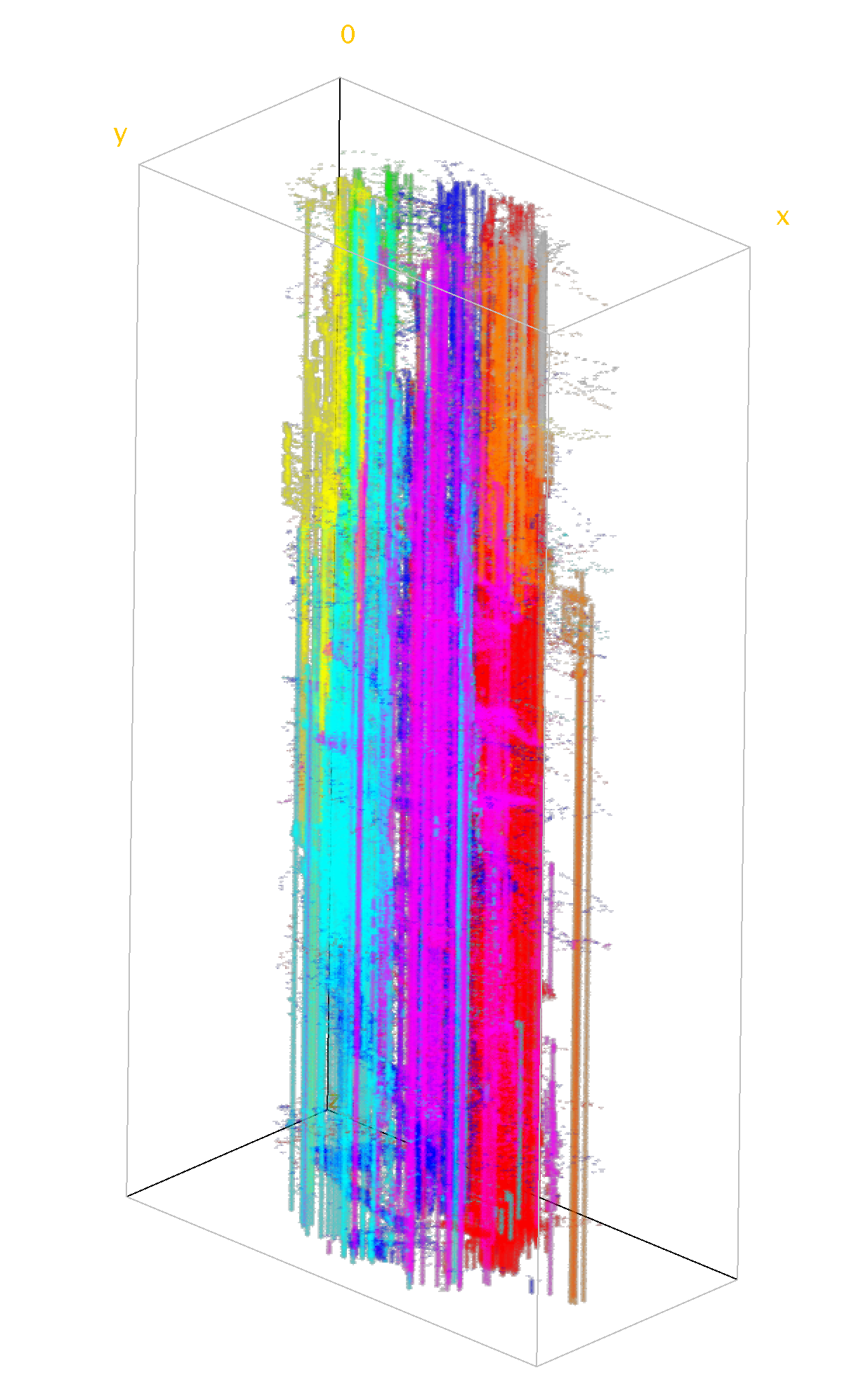

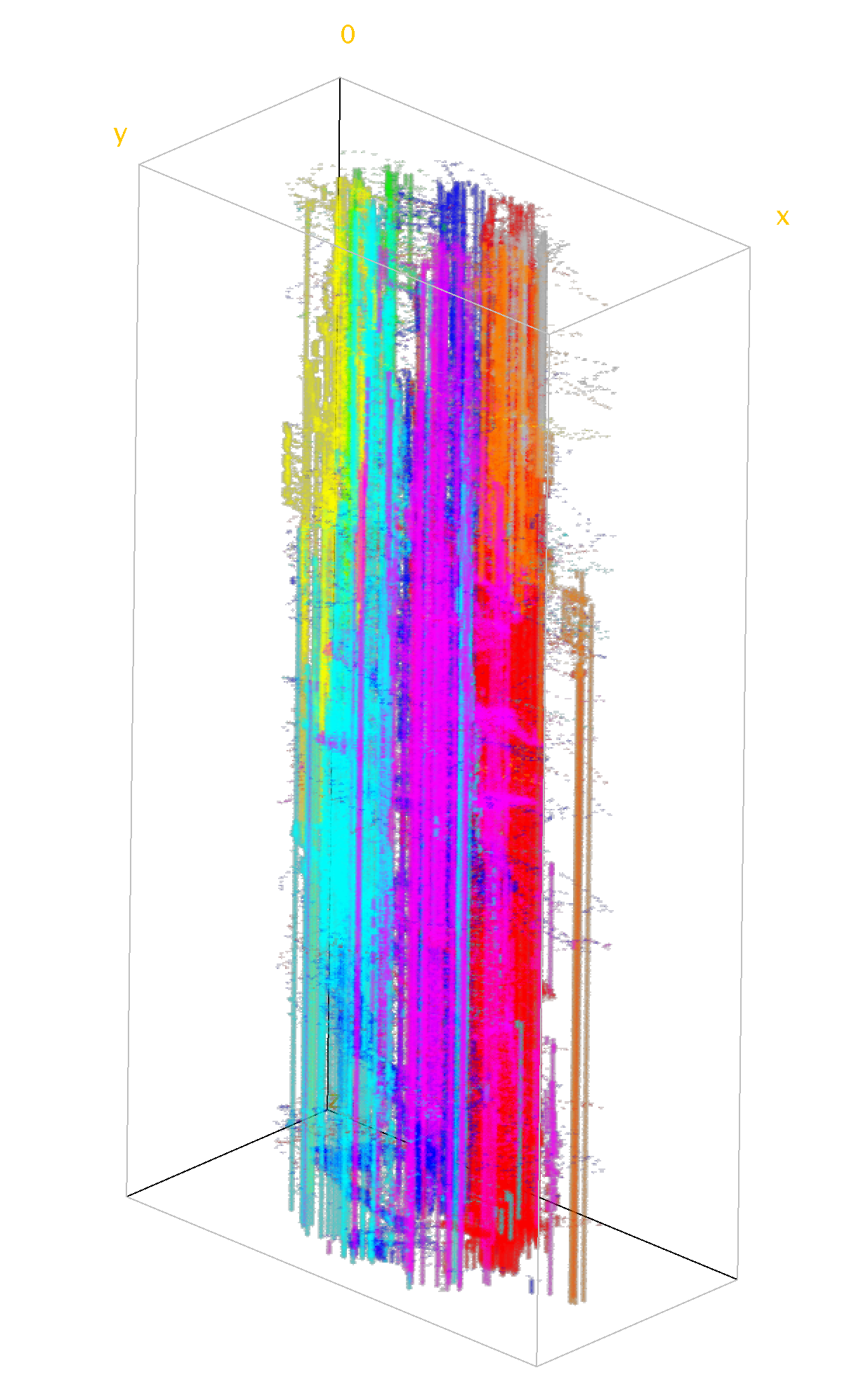

Here is the match from the beginning of the article in the form of a 3D volume:

The Z axis (shown here vertically) is time. In this volume, buildings create solid vertical lines, because they never change their position.

Having come closer, we can also see the movement of troops and workers through space and time. They look like thin paths:

Of particular interest are the weak spiral traces of scouts moving around the map. They are much more noticeable in matches for two players:

On the other hand, the matches for eight players are very chaotic.

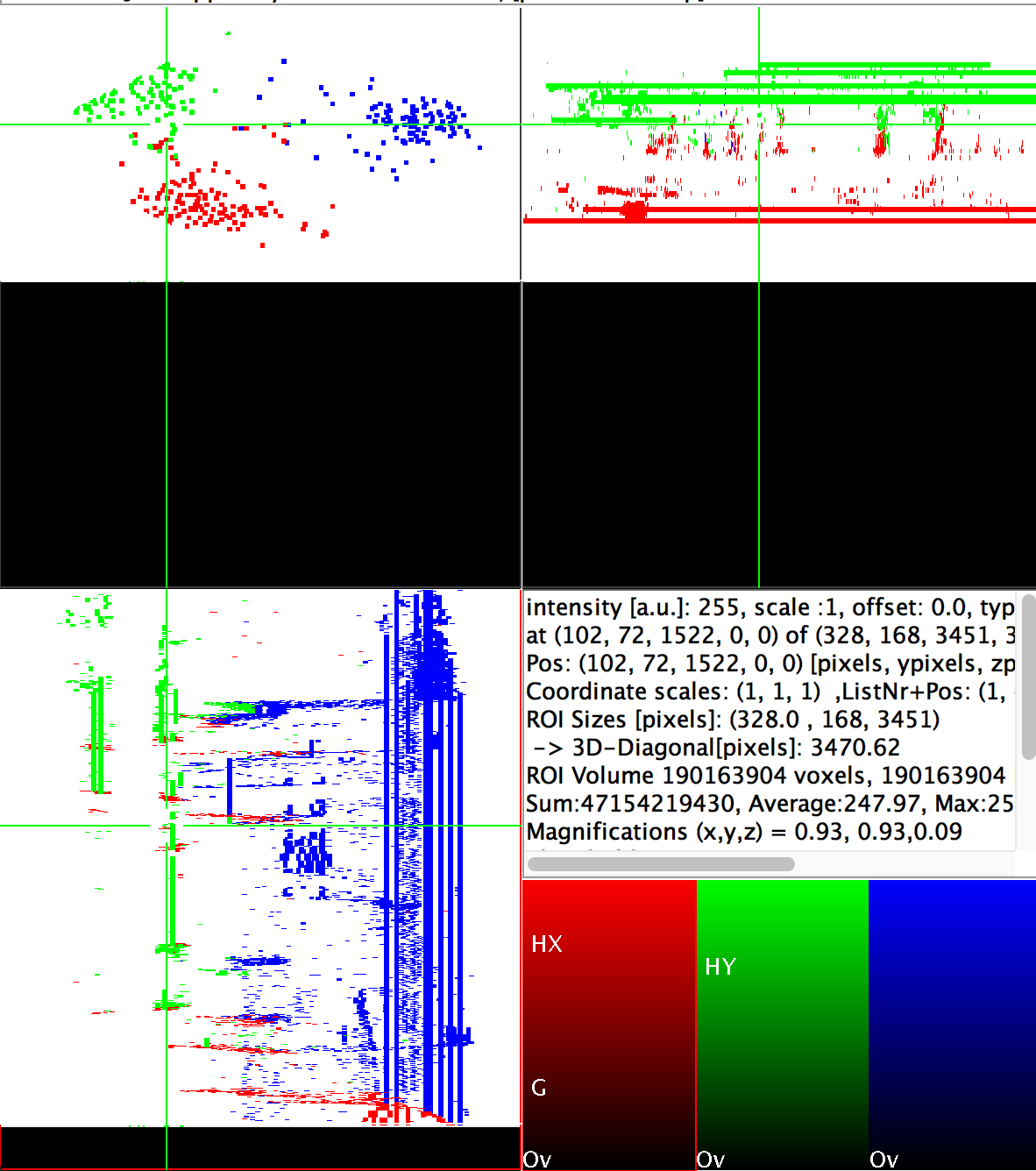

Finally, taking 2D through slices of the volume, we can look at the individual planes of the map over time.

Although the 3D projections are beautiful, I still find simple timelaps more interesting. The minimap is very similar to the view of the game, like a Petri dish: each side comes down to a bunch of multicolored pixels, and for some reason it’s very exciting to watch the colors expand, recede and conquer space. Perhaps from a sufficiently distant distance, this is how all battles look.

Scripts used for this project can be found here . They are very rude, so use them carefully. It may be fun to apply the same techniques to other games, in addition, most likely there are many other ways to study such data. Let me know if you create something interesting.

Begin research

I started by studying a match with three AI players on a medium sized map. Here is the initial state:

If the “First Player to Prepare” and taught me something, it is that it is absolutely normal to hold on to my childhood forever.

By taking screenshots of a mini-map every few seconds, we can create a time-lapse of the game. Each frame in the video shown below represents two seconds of real time. With a frequency of 24 frames per second, the two-hour game takes a much more comfortable two and a half minutes:

Here is the same match with the cleaned background. Reminds me of bacteria fighting in a petri dish:

When frames are superimposed on each other, this pattern is obtained:

Averaged blending of all frames shows standard routes on the map:

To better show the movement and actions, I also tried to consider only the visual differences between each of the frames:

And here is a visual representation of the coverage with each color:

Color cover card. As in other examples, it plays at a speed of 2x.

Combining the frames from this video into one image, moving from left to right, we get the following:

Handsomely.

Other matches

Watching the timelapse of AI behavior is fascinating, so I decided to capture several other matches to see what they looked like. Unless otherwise stated, all of them use the following parameters:

- Age of Empires II HD edition

- Conquest mode on a random map

- Randomly selected teams

- Beginning with the post-imperialist era

- Standard AI complexity

Here is the previous match and three replays. Despite the same starting conditions, each develops in its own way:

In these time-lapses, we begin to notice patterns of AI behavior. In many ways, they are quite ridiculous (at least on a standard difficulty) - the AI attacks, sending a chain of units to the target or retreating right after it has amassed an army on the border with the defenseless city of the enemy.

Matches for three players are especially interesting due to their dynamics. Sometimes two players unite against the third, sometimes the “royal battle” begins in the center of the map, and sometimes the third player conducts a covert attack, while the first and second players fight each other (the AI is not smart enough to actually plan all these maneuvers; they just appear naturally).

The lack of this dynamic makes two-player matches shorter and usually less interesting. Here are some examples:

The picture improves again when we go to four-player matches. In such matches, the fourth player is often destroyed in the early stages, which again leads to a match for three players.

I recorded most of these matches, leaving the game for the night. Most lasted one to two hours, but some have stabilized in stalemate situations. For example, in the four-player match shown below, everything starts very exciting, until the AI seems to be at a dead end. Having spent all the land resources, blue and yellow just surrendered, while red carelessly continues to endlessly fish.

Matches for eight players are more chaotic. In such matches, there are four teams of two players:

- Red + Blue

- Blue + Purple

- Gray + Orange

- Yellow + green

Golden fever

Fortress

In one of the games there were almost no fights:

Slices

Of course, there are many other ways to study the data, except for the timelapse. One of the most interesting is the projection of 2D slices of a mini-map onto a three-dimensional volume. For this analysis, I used ImageJ .

Here is the match from the beginning of the article in the form of a 3D volume:

The Z axis (shown here vertically) is time. In this volume, buildings create solid vertical lines, because they never change their position.

Having come closer, we can also see the movement of troops and workers through space and time. They look like thin paths:

Of particular interest are the weak spiral traces of scouts moving around the map. They are much more noticeable in matches for two players:

On the other hand, the matches for eight players are very chaotic.

Finally, taking 2D through slices of the volume, we can look at the individual planes of the map over time.

Completion

Although the 3D projections are beautiful, I still find simple timelaps more interesting. The minimap is very similar to the view of the game, like a Petri dish: each side comes down to a bunch of multicolored pixels, and for some reason it’s very exciting to watch the colors expand, recede and conquer space. Perhaps from a sufficiently distant distance, this is how all battles look.

Scripts used for this project can be found here . They are very rude, so use them carefully. It may be fun to apply the same techniques to other games, in addition, most likely there are many other ways to study such data. Let me know if you create something interesting.