"What I learned, having lived without artificial light"

- Transfer

Linda Geddes decided to live by candlelight for several weeks - without light bulbs, without screens. In the process, she discovered simple actions that everyone can resort to in order to sleep better and feel better.

A third of our lives we spend in a dream, or trying to sleep. But in the world, 24 hours a day and seven days a week living in artificial light, our sleep is increasingly threatened.

Many of us do not get up to the recommended 7-9 hours of sleep needed every night, and hardly get up in the morning - especially on weekdays. But not only the duration of sleep suffers. Since the discovery of the ability of light (especially the blue light emitted by devices like smartphones) to influence our biological clock, there is growing evidence that interacting with even a small amount of light in the evening or at night disrupts the quality of our sleep.

What happens if we turn off the lights? Will it improve our sleep, or will it bring some more benefit? How difficult will it be to do in a modern city?

One day, last winter, I decided to find out. I collaborated with sleep researchers Derk-Jan Dijk and Nayantara Santi of the University of Surrey, and we developed a program to sharply abandon artificial light at night and maximize interaction with natural light during the day — without abandoning office work and busy living with a family living in Bristol.

The discoveries made by me turned my attitude towards the light - and the way I live night and day. Now I can make simple daily decisions that can change how I sleep, how I feel, and even probably improve my cognitive abilities. Can you do it?

For thousands of years, people lived in sync with the natural cycle of light and darkness. This does not mean that everyone went to sleep when the sun went down. Studies of pre-industrial communities, such as tribes living today in Tanzania or Bolivia, suggest that people do not go to bed for several hours after dark, often socializing under the light of a fire. In fact, the duration of their sleep coincides with the duration of sleep of people living in industrialized countries, but the time more coincides with the natural cycle of day and night - they go to sleep and wake up before dawn.

“In modern societies, at least on weekdays, we do not sleep in harmony with our body clock,” says Dijk. Interaction with artificial light at night shifts our biological clock. But we still need to go to work in the morning, so we set the alarm - although the biological clock says that we should still sleep at this time.

In pre-industrial communities, for example, the Hadza tribe in Tanzania also seems to have far less sleep-related problems, such as insomnia. “When we asked members of the tribe if they thought they were sleeping well, almost everyone said that“ yes, everything is fine ”. Statistically, this does not correspond to what we see in the West, ”says David Samson, an anthropologist from the University of Toronto at Mississauga, who studied them.

Why it happens? Light allows us to see, but it affects many other systems. The morning light translates our internal clock back, and we become the larks, and the light at night delays the clock, putting us in the category of owls. Light also suppresses the hormone melatonin , which signals to the whole body that it is night - including the parts that regulate sleep. “In addition to vision, the light strongly affects our body and mind in a way that is not related to vision — it is worth remembering when we do not leave the house all day and the lights are lit until late at night,” says Santi, who showed that the evening light in our homes suppresses melatonin production and delays the onset of sleep.

However, the light also increases our vigilance. Its impact is comparable to double espresso. When you try to fall asleep, this stimulating effect hurts you, and when you get more light during the day, it makes you more alert. Light also stimulates areas of the brain responsible for mood.

“It is important that we create such a sequence of light exposure that we have enough light during the day and not too much in the evening,” says Dijk.

Despite this logic, it took a lot of effort to convince the family to allow me to switch to such an existence. When I told my husband that living by candlelight would be more romantic, he rolled his eyes. But it was much easier to convince him compared to my six-year-old daughter and four-year-old son. Something like this was our conversation:

Me: Children, we will try to live in the dark for several weeks.A few packs of marshmallow later, we agreed - although I agreed that my husband would sometimes be able to use electric light, and the children would watch TV if I was not around. Since I needed to maintain a normal work schedule, I also decided to keep the lights on until 6:00 pm, although after sunset I switched my laptop to night mode .

Daughter: But it will be scary.

Me: No, I think it will be fun. We will have candles.

Daughter: * Crying *

Me: Do not cry, please. It will be like a hike.

Son: Can we eat marshmallows?

The protocol worked like this: in the first week I tried to maximize my daylight by moving the desktop to the window, walking in the park after dropping my children to school, going out to eat outside and trying to do sports in nature. In the second week of the experiment, I tried to minimize the use of artificial light after 6:00 pm, using candles or dim lights instead. And then I combined these two approaches.

Between these experimental weeks, I lived as usual. These weeks served as a baseline.

To track the body's reactions, I used the actiwatch tracker to measure the amount of light I received, activity, and sleep quality. I also filled out a sleep diary and questionnaires to assess drowsiness and mood, and passed cognitive tests to assess short-term memory, attention, and speed of reaction. The last evening of each week I spent evenings in the dark, every hour took a sample of melatonin, which is produced in response to signals from biological clocks, and, therefore, serves as a marker of our internal clocks. “Melatonin is our dark hormone; it creates a biological night, ”says Marijke Gordijn, a chronobiologist at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, who measured my melatonin levels.

The idea was to see if the change in the schedule of light effects on my body translates my biological clock. We were interested to learn how the advantages predicted by larger laboratory tests under control will affect real life.

“We conducted many experiments, giving out a dose of light, and watching how biological clocks change,” says Gordiyn. “But if we want to apply these discoveries to help people, we need to know whether such actions will have the same effect when a person’s environment is more changeable.”

Turn on

On a bright sunny December morning, I found myself in a local park, trying to quietly work out on swings and horizontal bars instead of a bad pampa lesson at a fitness club. “Mom, what does this aunt do?” Asked the little boy.

It was winter, most people were warming themselves in their homes, and there was practically no one in the park. And I also had enough motivation. It is difficult to overcome the idea that after the onset of winter it will be cold and unpleasant on the street. However, I remembered how my Swedish acquaintance used to tell me: there is no bad weather, there are wrong clothes. And soon I realized that it was rarely as bad on the street as it might seem. The more I walked, the more I treated winter walks as pleasure, not as a duty.

Another morning I was sitting in the park with a cup of tea after I took the children to school, and took out my light meter. Illumination is measured in lux . In the summer, on a cloudless day outside, the illumination can reach 100,000 lux; on a cloudy day can fall to 1000 lux. Today the device showed 73,000 lux.

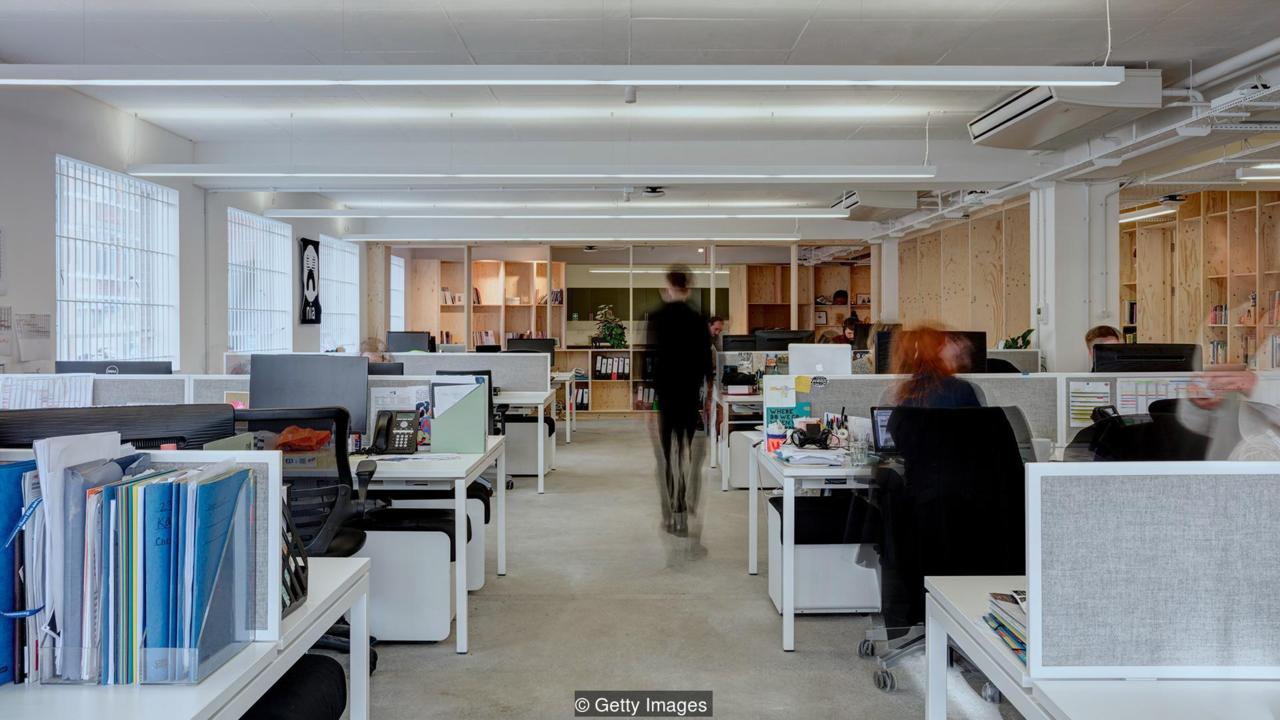

Returning to the room, I measured the illumination in the center of the office: 120 lux - even lower than 500 lux, as happens on the street immediately after sunset. In horror, I returned to my temporary table by the window, where it was colder, but lighter - 720 lux.

Despite my attempts to get more daylight in the experimental weeks, the average illumination from 7:30 to 18:00 was about 397 lux in the first week and only 180 lux in the second. This was most likely due to the fact that I spent most of my time indoors, working on a computer, and the sun was setting at 16:00. The likely cause of this fluctuation was the weather. In the first week on average per day, the sun shone brightly for 4.5 hours, and on the second - only 0.9 hours. It was still better than normal weeks, when my average illumination remained at 128 lux.

Difficulties delivered not only the weather. The first few nights of the experiment, we slept with open curtains to maximize my receipt of the dawn light. It is believed that at this time the light moves the internal clock back. But at night, due to street lighting, it was hard to sleep.

I was not the only one who faced this problem. In 2016, researchers said that people living in cities with a population of more than 500,000 people are exposed to night lighting from three to six times more than people living in small towns and rural areas. Those who live in more illuminated places sleep less, feel more tired during the day, and report less satisfaction from sleep. They also go to sleep and wake up later than people who live in darker places.

Hong Kong is considered the city with the highest light pollution in the world.

After a few days like this, I began to close the curtains and use the clock with the dawn simulation. It was an imperfect decision, because the light from these devices is not as bright as daylight. But it was better than nothing.

And, as if receiving more light during the day was not difficult enough, I still needed to get rid of the evening light in December, the darkest month of the year. Then I realized how useful artificial light at home. Cooking by candlelight every day was a problem, and chopping vegetables was a threat. I started cooking at an earlier time, which took my work time away, and I began to keep up less.

In the end, I came up with a different approach. I installed smart bulbs in the kitchen, which could dim the lighting and adjust the color with the app on the smartphone. This created a paradox: in order to remove the evoking blue light from the lamps, I had to be exposed to the blue light of a smartphone, so I did it during the day so as not to violate the conditions of the experiment. Now our kitchen at night shone with an eerie red-orange light. But at least we were able to cook again.

During the "dark weeks" I received an average of 0.5 lux from 18:00 to midnight, and the maximum was 59 lux. This is compared with an average illumination of 26 lux and a maximum of 9640 lux (I have no idea what a super-bright light source it was) during normal life - although the tracker on the wrist would not see the light from a smartphone or laptop. And this is important, because more and more evidence suggests that these devices can affect sleep.

In one of the studies in 2015, it is said that the use of an electronic book [ emitting light - apparently meant devices not with e-ink screens / approx. trans. ] before bedtime extended the time of falling asleep, delayed circadian rhythms, suppressed the phase of REM sleep. Also, participants reading an e-book felt more tired in the morning than people who read a printed book the same time.

Another recent study compared the reaction of people playing computer games on smartphones with conventional backlighting and removing blue in the evening. Players using conventional lighting felt more alert, and coped worse with the cognitive tests the next day, which may indicate that the quality of their sleep was affected.

My vow to avoid artificial light added complexity to my social activity. A few days before the experiment, my friend invited us to her house, to have a drink a few days before Christmas, in the middle of the “dark week”. When I explained my difficulty, she generously offered me to sit on the second floor in a room with candles, and communicate with people there. I politely refused, feeling, probably, as vegetarians feel after being invited to the steakhouse.

Instead, we invited friends to visit us, and they came: having fun, wondering, sometimes worried about what they would find. One family first refused the offer to stay for the New Year because they were worried that their son could knock over the candles. They changed their mind when I said that they could use the light in their bedroom (just in case, we kept all the candles where the child would not reach them).

After adapting to change, life without artificial light was quite enjoyable. Conversations were easier, the guests talked about how calm and relaxed they feel in dim light. Another advantage was that the children calmed down easier in the evenings, although we did not collect data on them.

Did it somehow affect my sleep or mental abilities? There was a tendency to go to sleep earlier during the experimental weeks — in particular, during the week when I combined an increased amount of light during the day with a reduced light in the evening. This week, on average, I went to bed at 23:00, compared to 23:35 at the usual time.

It was December, I had a lot of social responsibilities, so sometimes I ignored the signals of my body regarding sleep, and went to bed later. Researchers often encounter this problem in their work. “People have social responsibilities, and it’s very difficult for them to obey what their internal clocks say,” says Marianna Figueiro, director of the Center for Light Studies in Troy. "We constantly struggle with our physiology."

And still, in those days when the amount of light was increased during the day, and reduced in the evening, in the evenings I was much more sleepy. My body began to produce the hormone of the dark, melatonin, about 1.5 hours earlier in the days when I increased the amount of daylight, and two hours earlier when I avoided light in the evening.

This sequence was observed in other studies. Kenneth Wright from Boulder University in Colorado, like me, has long been interested in how modern lighting affects our internal clocks. In 2013, he sent eight people on a hike to the Rocky Mountains in Colorado for a week in the summer, and measured how this affected their sleep. “The hike is an obvious way to get out of the modern light environment and use only natural light,” says Wright.

Before the trip, the average bedtime among the participants was 00:30, and the awakening time was 8:00. By the end of the hike, these marks moved back about 1.2 hours. Participants also began to produce melatonin two hours earlier after eliminating artificial light — although they did not sleep any longer.

Recently, Wright repeated this study in the winter. This time, he found that the participants in the natural lighting conditions went to sleep 2.5 hours earlier, and woke up at about the same time as at home. This meant that they slept for about 2.3 hours more . “We think it was because people used to go back to their tents to keep warm, so they let themselves sleep longer,” Wright says.

Unlike his subjects, I did not feel a significant increase in the duration of sleep during the experiments - although there was a slight increase in the duration and effectiveness of sleep (the ratio of time spent in sleep to total time spent in bed). However, this was not statistically significant, that is, it could just be random. The reason, perhaps, was that I lived in a relatively warm house, which made it easier for me to withstand my internal clocks. And also in the mornings I was forced to get up at the same time as children - and sometimes they would wake me up at night.

But when I correlated my dream with the amount of light received by the day, an interesting pattern emerged. In the brightest days I went to bed earlier. For every 100 lx, which increased the amount of daylight I received, I experienced an improvement in sleep efficiency by 1% and received an additional 10 minutes of sleep.

I also felt more attentive during the experimental weeks — and especially during those weeks when I received more daylight.

This pattern was observed in other studies. The US General Services Administration is the largest landowner in the country. Many public buildings serviced by it were either designed to increase the amount of daylight, or were reconstructed for this, so the administration was interested to see if this somehow affected the health of the people working in these buildings. Working with Figueiro from the Center for the Study of Light, they chose four such buildings and another Administration building in Washington, DC - a former warehouse, which at that time did not receive much daylight. Workers were asked to wear devices around their necks that collected information about access to daylight, and also fill out questionnaires on the subject of mood and sleep daily — for one week in summer, and then for one week in winter.

When the data began to arrive, they initially caused despondency. Despite attempts to increase the amount of daylight in the workplace, many employees of the Administration did not receive it. “Our research has found that if you are a meter or more from the window, you lose daylight,” says Figueiro. - But not only the distance from the window plays a role. There are partitions, blinds. If you have a window, it does not mean that you get a good portion of daylight. ”

Moving further, the Figueiro team divided office workers into those who received enough stimuli for circadian rhythms — bright enough or enough blue light to activate the circadian system — and those who received few such stimuli.

People who received a lot of stimuli quickly fell asleep and slept longer. The light was particularly influential in the morning: those who received a good dose of light from 8 to 12 hours fell asleep on average for 18 minutes, compared with the others who had fallen asleep on average for 45 minutes. They slept for 20 minutes more. Their sleep efficiency was 2.8% higher. They reported significantly fewer sleep problems. In winter, this connection was more pronounced, perhaps because people had less opportunity to receive a dose of daylight on the way to work .

Gordian also recently published a study that found that people slept the better, the longer they were exposed to daylight. In this study, subjects were connected to the polysomnography apparatus.who recorded the details of their sleep. “People had more deep sleep, and it was less fragmented after receiving more daylight,” says Gordiyn.

Essence of the world

Until recently, scientists believed that the desire to sleep is caused by two independent systems: circadian, affecting sleep time, and homeostatic , tracking how long we are awake, and accumulating the power of coercion to sleep.

It was known that light changes the time of going to bed through the circadian system. But the recent work of Samer Hattar from the University of Maryland says that the photosensitive cells of the eye that control the circadian system are also connected to the homeostatic one. “We believe that the time of exposure to light and its intensity modulate not only the circadian aspect of sleep, but also homeostatic coercion to sleep,” says Gordiyn.

Daylight affects mood. Administration staff who received more morning light, rated their level of depression below the rest. Another study demonstrated that morning and daylight may affect the symptoms of off-season depression for the better.

“Perhaps this is due to the fact that people are more accustomed to the cycle of light and dark, and sleep better,” says Figueiro. In her study, subjects who received more circadian stimuli during the day were more active during the daytime and less active at night, that is, their sleep coincided better with the internal clock.

These data are consistent with studies of office workers in Britain. In March 2007, Diyk and his colleagues replaced light bulbs.on two floors of an office building in northern England where the electronics company was located. Workers on the same floor received light with a high content of the blue component for four weeks; on the other, the light was white. Then the light bulbs were swapped, in connection with which both groups experienced the influence of both types of light. It was found that exposure to blue light improved the vigilance and efficiency of workers, and also reduced their fatigue in the evenings. In addition, they reported that they sleep better and longer.

This coincides with my observations. Immediately after waking up and before going to sleep in the evenings, I filled out a questionnaire to assess my feelings. The results show that my mood in the early morning was much more positive during the experimental weeks, compared to the usual. There was also a tendency to reduce negative emotions in the evenings.

And although I did not evaluate my mood strictly during the day, I felt more energetic and elevated in those weeks when I spent more time on the street. And on the basis of this experience, I moved to the camp of fans of classes in the air. I also learn to enjoy long winter evenings, and I consider this season the opportunity to make a home more comfortable with candles, instead of suffering because of darkness.

Even my daughter changed her mind. By the end of the experiment, I asked her if she was waiting for the opportunity to turn on the light again. “No,” she said. “It was wonderful, the candles are very relaxing.” My four-year-old son insisted on the lighting: he wanted to see what we eat at dinner.

And although the results of my cognitive tests did not reach statistical significance, there was a tendency towards accelerating the speed of the reaction, as well as to a slight improvement in the test results, where it was necessary to remember which of the boxes was hidden a token.

Studies by Gills Vanderwall from the University of Liege in Belgium and Dijk showed that exposure to bright light activates areas of the brain that are responsible for mindfulness - although in these studies the effects did not last long.

But in another study, scientists from the University of Charité in Berlin found that the energy-giving effect of light continues until the end of the day. When the subjects were exposed to bright light with a high content of the blue component in the morning, they told them that they felt less sleepy in the evenings, and their reaction speed in the evening remained the same and did not fall. Also, the bright light in the morning, apparently, protected them from the effects of exposure to the biological clock of blue light in the evening. This discovery coincides with the current mathematical models that describe how light affects biological clocks and human sleep.

This confirms the idea that bright and blue morning light can be an effective countermeasure against evening artificial light, especially in the dark season, when there is not enough daylight. That is, we do not have to spend evenings in the dark or give up computers and gadgets.

“The impact of light in the evening depends strongly on the kind of light that affected you in the morning,” says Dieter Kunz, who participated in the study. “When we talk about children sticking to the iPad in the evenings, this pastime hurts them if they spend the whole day in biological darkness. But if they are in the light during the day, it may not matter. ”

Everything is ridiculously simple. But spending more time on the street during the day and dim the lights in the evenings can really become a recipe for improving sleep and health. For thousands of years, people lived in sync with the sun. Perhaps it is time for us to make friends again.

Linda Geddes is the author of the book 2019, Chasing the Sun: The Amazing Science of Sunlight, and How to Survive in the World around the Clock.