Successful Branching Model for Git

- Transfer

Translation of Vincent Driessen: A successful Git branching model

article In this article I present a development model that I have been using for all my projects (both working and private) for the past year, and which has shown itself to be good. For a long time I was going to write about her, but still have not found any free time. I will not talk about all the details of the project, I will only touch on the branching and release management strategies.

It uses Git as a version control tool for all source code .

For a full discussion of all the advantages and disadvantages of Git in comparison with centralized version control systems, refer to the worldwide network . There you will find a sufficient number of disputes on this topic. Personally, as a developer, I currently prefer Git to all other tools. Git really was able to change the attitude of developers to the processes of merging and branching. In the classic CVS / Subversion world from which I came, branching and merging are usually considered dangerous (“beware of merge conflicts, they bite painfully!”), And therefore are carried out as rarely as possible.

But with Git, these actions become extremely simple and cheap, and therefore, in fact, they become the central elements of a normal dailywork process. Just compare: in books on CVS / Subversion branching and merging are usually discussed in the last chapters (for advanced users), while in any book about Git they are mentioned already in the third chapter (basics).

Due to their simplicity and predictability, branching and merging are no longer actions to be wary of. Version control tools can now help with branching and merging more than any other.

But stop talking about tools, let's move on to the development model. The model that I want to introduce is, in fact, just a set of procedures that each team member performs, so that together they can achieve high manageability of the development process.

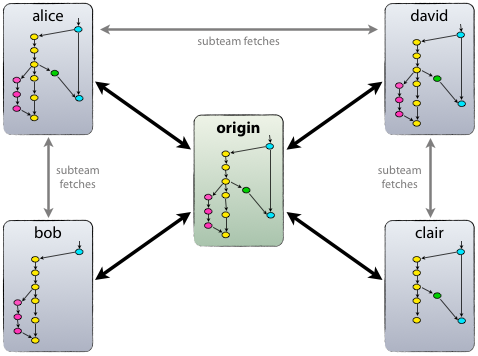

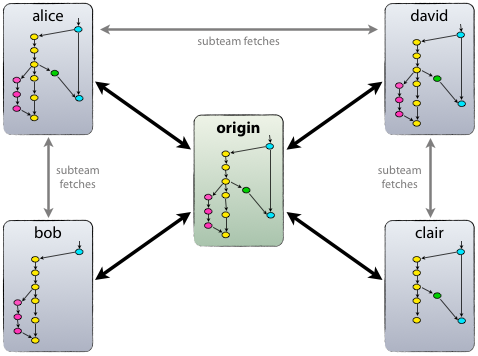

The proposed branching model relies on a project configuration that contains one central “true” repository. I note that this repository is only considered central (since Git is DVCS, it does not have such a thing as the main repository at a technical level). We will call this repository the term origin, because this name is already familiar to all Git users.

Each developer picks up and publishes the changes (pull & push) in origin. But, in addition to a centralized push-pull relationship, each developer can also pick up changes from other colleagues within his micro-team. For example, this method may be convenient in a situation where two or more developers are working together on a big new feature, but cannot publish work in progress in origin ahead of time. The picture above shows the subgroups of Alice and Bob, Alice and David, Claire and David.

Technically, this is easy: Alice creates a remote Git branch called bob that points to Bob's repository, and Bob does the same with her repository.

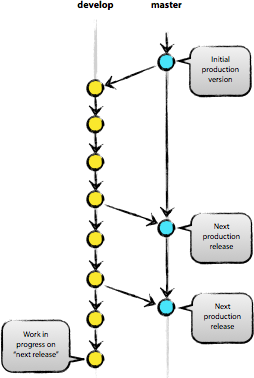

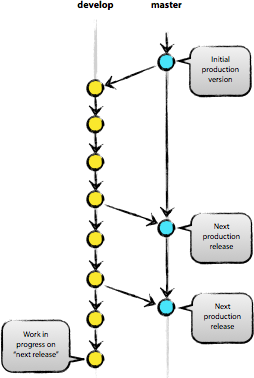

The core of the development model is no different from most existing models. The central repository contains two main branches that exist all the time.

The master branch is created when the repository is initialized, which should be familiar to every Git user. In parallel to it, we also create a development branch called develop.

We consider the origin / master branch to be the main one. That is, the source code in it must be in production-ready state at any arbitrary point in time.

The origin / develop branch we consider to be the main branch for development. The code stored in it at any time should contain the latest published changes necessary for the next release. This branch can also be called "integration". It serves as a source for the assembly of automatic night builds.

When the source code in the development branch (develop) reaches a stable state and is ready for release, all changes must be in a certain way poured into the main branch (master) and tagged with the release number. Below we will consider this process in detail.

Therefore, every time changes are merged into the main branch (master), by definition we get a new release. We try to take this rule very strictly, so, in principle, we could use Git hooks to automatically collect our products and put them on production servers at each commit to the main branch (master).

In addition to the main branches master and develop, our development model contains a number of types of auxiliary branches that are used to parallelize development between team members, to simplify the implementation of new features, to prepare releases, and to quickly fix problems in the production version of the application. Unlike main branches, these branches always have a limited lifespan. Each of them ultimately leaves sooner or later.

We use the following types of branches:

Each type of branch has its own specific purpose and a strict set of rules, from which branches they can be generated, and into which they must merge. Now we will consider them in turn.

Of course, from a technical point of view, these branches have nothing "specific". Division of branches into categories exists only in terms of how they are used. And everything else is the good old branches of Git.

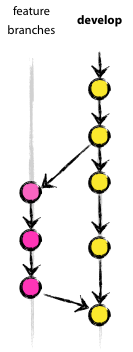

May originate from: develop

Must merge into: develop

Naming convention: everything except master, develop, release- * or hotfix- *

Feature branches, also sometimes referred to as topic branches, are used to develop new features that should appear in current or future releases. At the beginning of work on functionality (features), it may still not be known in which particular release it will be added. The meaning of the existence of a feature branch is that it lives as long as the development of this functionality (features) continues. When the work in the branch is completed, the latter merges back into the main development branch (which means that the functionality will be added to the upcoming release) or deleted (in the case of an unsuccessful experiment).

Feature branches typically exist in developer repositories, but not in the main repository (origin).

When you start working on new functionality, a branch is made from the develop branch.

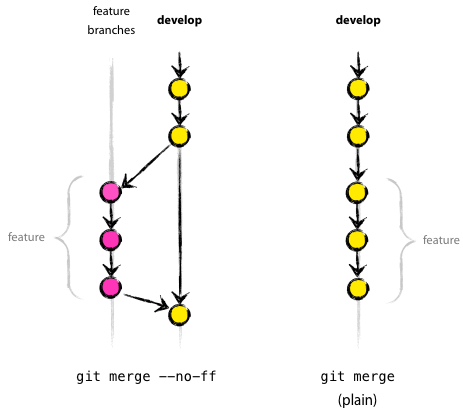

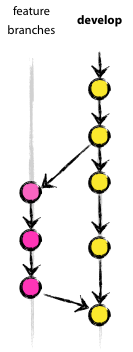

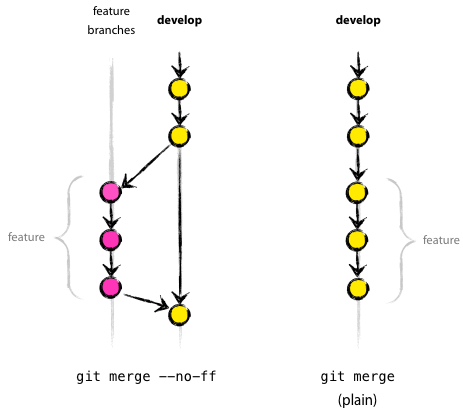

The completed functionality (feature) merges back into the develop branch and gets into the next release. The --no-ff flag forces Git to always create a new commit object during a merge, even if the merge can be done using the fast-forward algorithm. This allows you not to lose information that the branch existed, and groups together all the changes made. Compare: In the second case, it is impossible to see in the change history exactly which commit objects together form the functionality - for this you will have to manually read all the messages in the commits. In this case, it is impossible to cancel the entire functionality (i.e., a group of commits) without a headache, and with the --no-ff flag this is done elementarily.

Of course, this approach creates some additional number of (empty) commit objects, but the resulting benefit more than justifies such a price.

Unfortunately, I have not yet found how you can configure Git so that --no-ff is the default merge behavior. But this method must be implemented.

May originate from: develop

Must merge into: develop and master

Naming convention: release- *

Release branches are used to prepare for the release of new versions of the product. They allow you to place the final points over i before the release of a new version. In addition, minor corrections can be added to them, as well as metadata for the next release (version number, build date, etc.). When all this work is submitted to the release branch, the main develop branch is cleared to add further features (which will be included in the next big release).

A new release branch must be generated at a time when the state of the development branch fully or almost completely meets the requirements corresponding to the new release. At least all the necessary functionality intended for this release is already poured into the develop branch. The functionality intended for the next releases may not be infused. It is even better if the branches for these functionalities wait until the current release branch is detached from the develop branch.

The next release gets its version number only at the moment when a new branch is created for it, but in no case earlier. Up to this point, the development branch contains changes for the “new release”, but until the release branch is separated, it is not known whether this release will have version 0.3, or 1.0, or some other version. The decision is made when creating a new release branch and depends on the project version numbering rules adopted by the project.

A release branch is created from a develop branch. Let, for example, the current released release has version 1.1.5, and on the way a new big release full of changes. The develop branch is ready for the “next release”, and we decide that this release will have version 1.2 (and not 1.1.6 or 2.0). In this case, we create a new branch and give it a name corresponding to the new version of the project: We created a new branch, switched to it, and then set the version number (bump version number). In our example, bump-version.sh is a fictional script that modifies some files in a working copy by writing a new version to them. (Of course, you can also make these changes manually; I just draw your attention to the fact that some files are changing.) Then we commit with the new version of the project.

This new branch may exist for some time, until the new release is finally ready for release. During this time, corrections of found bugs can be added to this branch (and not to develop). But adding major new changes to this branch is strictly prohibited. They should always flow into the develop branch and wait for the next big release.

When we decide that the release branch is finally ready for release, we need to do a few things. First of all, the release branch merges into the main branch (I remind you, each commit in master is, by definition, a new release). Further, this commit in master should be tagged so that later on you can easily access any existing version of the product. Finally, changes made to the release branch must be added back to the development branch (develop branch) so that future releases also contain bug fixes.

First two steps in Git: Now the release is published and tagged. Note : if desired, you can also use the -s or -u <key> flags to sign the tag cryptographically.

To save changes in future releases, we must integrate these changes back into development. We do it like this: This step, in principle, can lead to a merger conflict (it often happens that the cause of the conflict is a change in the version number of the project). If this happens, correct them and issue a commit. Now we have finally finished with the release branch. You can delete it, because we will no longer need it:

May originate from: master

Must merge into: develop and master

Naming convention: hotfix- *

Hotfix branches are very similar to release branches, since they are also used to prepare new product releases, unless unplanned . They are caused by the need to immediately correct the undesirable behavior of the production version of the product. When a bug is found in the production version that needs to be fixed immediately, a new branch is generated from the corresponding master version tag for the master branch to work on the fix.

The meaning of its existence is that the team’s work on the develop branch can continue quietly, while someone alone is preparing a quick fix for the production version.

Hotfix branches are created from the master branch. Let, for example, the current production release has version 1.2, and a serious bug is detected in it (suddenly!). And the changes in the development branch (develop) are not stable enough to be published in a new release. But we can create a new patch branch and start working on a solution to the problem: Remember to update the version number after creating the branch! Now you can fix the bug, and publish the changes with at least one commit, at least several.

When the bug is fixed, the changes must be poured back into the main branch (master), as well as into the development branch (develop), to ensure that this fix will appear in the next release. This is very similar to how a release branch is closed.

First of all, you need to update the main branch (master) and tag the new version with a tag. Note : if you wish, you can also use the -s or -u <key> flags to sign the tag cryptographically. The next step is moving the fix to the develop branch. This rule has one exception: if at the moment there is a release branch, then the hotfix branch should merge into it, and not into the develop branch

. In this case, corrections will go into the development branch along with the entire release branch when it is closed. (Although, if working in develop requires an immediate bug fix and cannot wait for the current release to be completed, you can still patch the bugfix into the develop branch and it will be completely safe).

And finally, delete the temporary branch:

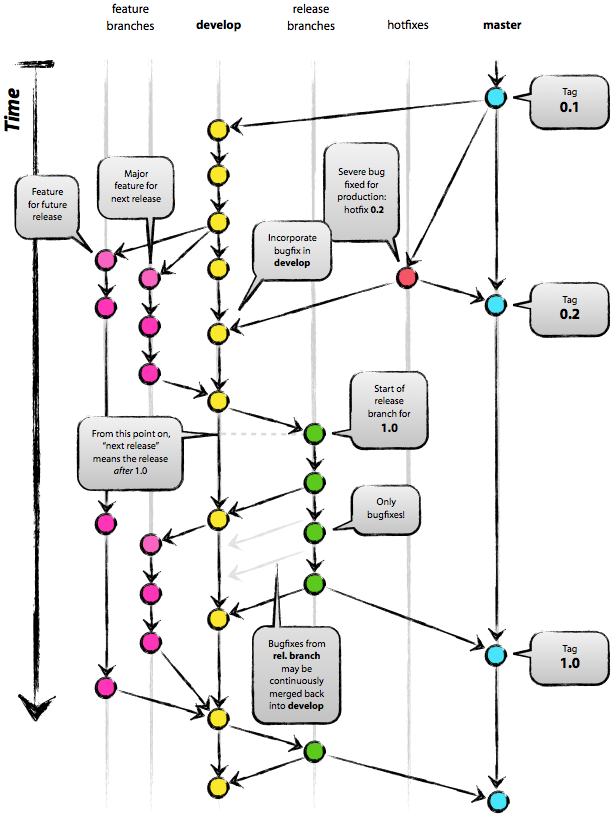

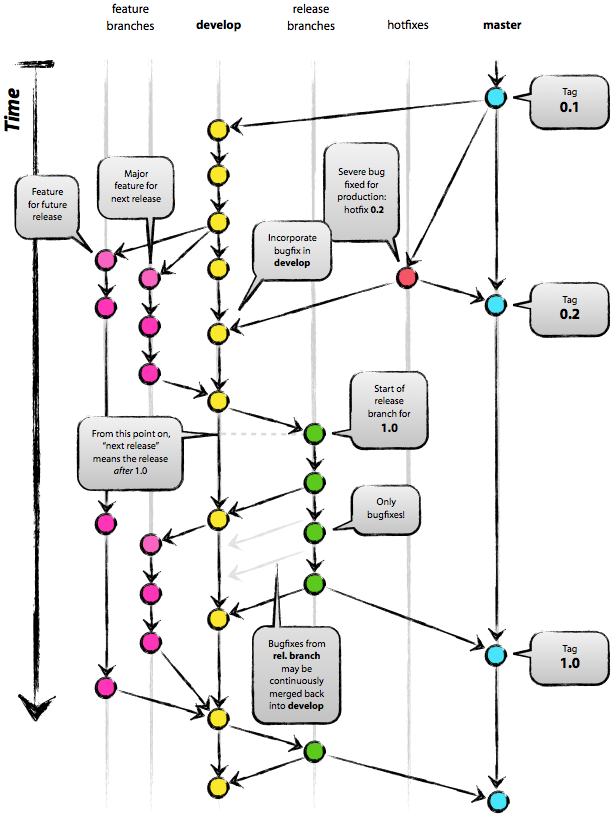

Although there is absolutely nothing fundamentally new in this branching model, the “big picture” with which this article begins has proved itself in our projects from the best side. It forms an elegant mental model, which is easy to fully capture with one glance, and which allows you to form a team's joint understanding of the branching and merging processes that are acting on the project.

The high quality PDF version of this image is free to download here . Print it and hang it on your wall so that it can be accessed at any time.

Note translator: the article is not new, the link to the original has already appeared on Habr. This translation is for those to whom English is still not so easy (as well as for my colleagues, among whom I am engaged in propaganda, hehe). To automate the procedures described in the article, the author created a gitflow project, which can be found on github .

article In this article I present a development model that I have been using for all my projects (both working and private) for the past year, and which has shown itself to be good. For a long time I was going to write about her, but still have not found any free time. I will not talk about all the details of the project, I will only touch on the branching and release management strategies.

It uses Git as a version control tool for all source code .

Why git?

For a full discussion of all the advantages and disadvantages of Git in comparison with centralized version control systems, refer to the worldwide network . There you will find a sufficient number of disputes on this topic. Personally, as a developer, I currently prefer Git to all other tools. Git really was able to change the attitude of developers to the processes of merging and branching. In the classic CVS / Subversion world from which I came, branching and merging are usually considered dangerous (“beware of merge conflicts, they bite painfully!”), And therefore are carried out as rarely as possible.

But with Git, these actions become extremely simple and cheap, and therefore, in fact, they become the central elements of a normal dailywork process. Just compare: in books on CVS / Subversion branching and merging are usually discussed in the last chapters (for advanced users), while in any book about Git they are mentioned already in the third chapter (basics).

Due to their simplicity and predictability, branching and merging are no longer actions to be wary of. Version control tools can now help with branching and merging more than any other.

But stop talking about tools, let's move on to the development model. The model that I want to introduce is, in fact, just a set of procedures that each team member performs, so that together they can achieve high manageability of the development process.

Decentralized but centralized

The proposed branching model relies on a project configuration that contains one central “true” repository. I note that this repository is only considered central (since Git is DVCS, it does not have such a thing as the main repository at a technical level). We will call this repository the term origin, because this name is already familiar to all Git users.

Each developer picks up and publishes the changes (pull & push) in origin. But, in addition to a centralized push-pull relationship, each developer can also pick up changes from other colleagues within his micro-team. For example, this method may be convenient in a situation where two or more developers are working together on a big new feature, but cannot publish work in progress in origin ahead of time. The picture above shows the subgroups of Alice and Bob, Alice and David, Claire and David.

Technically, this is easy: Alice creates a remote Git branch called bob that points to Bob's repository, and Bob does the same with her repository.

Main branches

The core of the development model is no different from most existing models. The central repository contains two main branches that exist all the time.

- master

- develop

The master branch is created when the repository is initialized, which should be familiar to every Git user. In parallel to it, we also create a development branch called develop.

We consider the origin / master branch to be the main one. That is, the source code in it must be in production-ready state at any arbitrary point in time.

The origin / develop branch we consider to be the main branch for development. The code stored in it at any time should contain the latest published changes necessary for the next release. This branch can also be called "integration". It serves as a source for the assembly of automatic night builds.

When the source code in the development branch (develop) reaches a stable state and is ready for release, all changes must be in a certain way poured into the main branch (master) and tagged with the release number. Below we will consider this process in detail.

Therefore, every time changes are merged into the main branch (master), by definition we get a new release. We try to take this rule very strictly, so, in principle, we could use Git hooks to automatically collect our products and put them on production servers at each commit to the main branch (master).

Auxiliary branches

In addition to the main branches master and develop, our development model contains a number of types of auxiliary branches that are used to parallelize development between team members, to simplify the implementation of new features, to prepare releases, and to quickly fix problems in the production version of the application. Unlike main branches, these branches always have a limited lifespan. Each of them ultimately leaves sooner or later.

We use the following types of branches:

- Feature branches

- Release branches

- Hotfix branches

Each type of branch has its own specific purpose and a strict set of rules, from which branches they can be generated, and into which they must merge. Now we will consider them in turn.

Of course, from a technical point of view, these branches have nothing "specific". Division of branches into categories exists only in terms of how they are used. And everything else is the good old branches of Git.

Feature branches

May originate from: develop

Must merge into: develop

Naming convention: everything except master, develop, release- * or hotfix- *

Feature branches, also sometimes referred to as topic branches, are used to develop new features that should appear in current or future releases. At the beginning of work on functionality (features), it may still not be known in which particular release it will be added. The meaning of the existence of a feature branch is that it lives as long as the development of this functionality (features) continues. When the work in the branch is completed, the latter merges back into the main development branch (which means that the functionality will be added to the upcoming release) or deleted (in the case of an unsuccessful experiment).

Feature branches typically exist in developer repositories, but not in the main repository (origin).

Creating a feature branch

When you start working on new functionality, a branch is made from the develop branch.

$ git checkout -b myfeature develop

Switched to a new branch "myfeature"Adding Completed Functionality to Develop

The completed functionality (feature) merges back into the develop branch and gets into the next release. The --no-ff flag forces Git to always create a new commit object during a merge, even if the merge can be done using the fast-forward algorithm. This allows you not to lose information that the branch existed, and groups together all the changes made. Compare: In the second case, it is impossible to see in the change history exactly which commit objects together form the functionality - for this you will have to manually read all the messages in the commits. In this case, it is impossible to cancel the entire functionality (i.e., a group of commits) without a headache, and with the --no-ff flag this is done elementarily.

$ git checkout develop

Switched to branch 'develop'

$ git merge --no-ff myfeature

Updating ea1b82a..05e9557

(Отчёт об изменениях)

$ git branch -d myfeature

Deleted branch myfeature (was 05e9557).

$ git push origin develop

Of course, this approach creates some additional number of (empty) commit objects, but the resulting benefit more than justifies such a price.

Unfortunately, I have not yet found how you can configure Git so that --no-ff is the default merge behavior. But this method must be implemented.

Release branches

May originate from: develop

Must merge into: develop and master

Naming convention: release- *

Release branches are used to prepare for the release of new versions of the product. They allow you to place the final points over i before the release of a new version. In addition, minor corrections can be added to them, as well as metadata for the next release (version number, build date, etc.). When all this work is submitted to the release branch, the main develop branch is cleared to add further features (which will be included in the next big release).

A new release branch must be generated at a time when the state of the development branch fully or almost completely meets the requirements corresponding to the new release. At least all the necessary functionality intended for this release is already poured into the develop branch. The functionality intended for the next releases may not be infused. It is even better if the branches for these functionalities wait until the current release branch is detached from the develop branch.

The next release gets its version number only at the moment when a new branch is created for it, but in no case earlier. Up to this point, the development branch contains changes for the “new release”, but until the release branch is separated, it is not known whether this release will have version 0.3, or 1.0, or some other version. The decision is made when creating a new release branch and depends on the project version numbering rules adopted by the project.

Creating a release branch

A release branch is created from a develop branch. Let, for example, the current released release has version 1.1.5, and on the way a new big release full of changes. The develop branch is ready for the “next release”, and we decide that this release will have version 1.2 (and not 1.1.6 or 2.0). In this case, we create a new branch and give it a name corresponding to the new version of the project: We created a new branch, switched to it, and then set the version number (bump version number). In our example, bump-version.sh is a fictional script that modifies some files in a working copy by writing a new version to them. (Of course, you can also make these changes manually; I just draw your attention to the fact that some files are changing.) Then we commit with the new version of the project.

$ git checkout -b release-1.2 develop

Switched to a new branch "release-1.2"

$ ./bump-version.sh 1.2

Files modified successfully, version bumped to 1.2.

$ git commit -a -m "Bumped version number to 1.2"

[release-1.2 74d9424] Bumped version number to 1.2

1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)This new branch may exist for some time, until the new release is finally ready for release. During this time, corrections of found bugs can be added to this branch (and not to develop). But adding major new changes to this branch is strictly prohibited. They should always flow into the develop branch and wait for the next big release.

Closing a Release Branch

When we decide that the release branch is finally ready for release, we need to do a few things. First of all, the release branch merges into the main branch (I remind you, each commit in master is, by definition, a new release). Further, this commit in master should be tagged so that later on you can easily access any existing version of the product. Finally, changes made to the release branch must be added back to the development branch (develop branch) so that future releases also contain bug fixes.

First two steps in Git: Now the release is published and tagged. Note : if desired, you can also use the -s or -u <key> flags to sign the tag cryptographically.

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ git merge --no-ff release-1.2

Merge made by recursive.

(Отчёт об изменениях)

$ git tag -a 1.2To save changes in future releases, we must integrate these changes back into development. We do it like this: This step, in principle, can lead to a merger conflict (it often happens that the cause of the conflict is a change in the version number of the project). If this happens, correct them and issue a commit. Now we have finally finished with the release branch. You can delete it, because we will no longer need it:

$ git checkout develop

Switched to branch 'develop'

$ git merge --no-ff release-1.2

Merge made by recursive.

(Отчёт об изменениях)$ git branch -d release-1.2

Deleted branch release-1.2 (was ff452fe).Hotfix branches

May originate from: master

Must merge into: develop and master

Naming convention: hotfix- *

Hotfix branches are very similar to release branches, since they are also used to prepare new product releases, unless unplanned . They are caused by the need to immediately correct the undesirable behavior of the production version of the product. When a bug is found in the production version that needs to be fixed immediately, a new branch is generated from the corresponding master version tag for the master branch to work on the fix.

The meaning of its existence is that the team’s work on the develop branch can continue quietly, while someone alone is preparing a quick fix for the production version.

Creating a hotfix branch

Hotfix branches are created from the master branch. Let, for example, the current production release has version 1.2, and a serious bug is detected in it (suddenly!). And the changes in the development branch (develop) are not stable enough to be published in a new release. But we can create a new patch branch and start working on a solution to the problem: Remember to update the version number after creating the branch! Now you can fix the bug, and publish the changes with at least one commit, at least several.

$ git checkout -b hotfix-1.2.1 master

Switched to a new branch "hotfix-1.2.1"

$ ./bump-version.sh 1.2.1

Files modified successfully, version bumped to 1.2.1.

$ git commit -a -m "Bumped version number to 1.2.1"

[hotfix-1.2.1 41e61bb] Bumped version number to 1.2.1

1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)$ git commit -m "Fixed severe production problem"

[hotfix-1.2.1 abbe5d6] Fixed severe production problem

5 files changed, 32 insertions(+), 17 deletions(-)Closing a patch branch

When the bug is fixed, the changes must be poured back into the main branch (master), as well as into the development branch (develop), to ensure that this fix will appear in the next release. This is very similar to how a release branch is closed.

First of all, you need to update the main branch (master) and tag the new version with a tag. Note : if you wish, you can also use the -s or -u <key> flags to sign the tag cryptographically. The next step is moving the fix to the develop branch. This rule has one exception: if at the moment there is a release branch, then the hotfix branch should merge into it, and not into the develop branch

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ git merge --no-ff hotfix-1.2.1

Merge made by recursive.

(Отчёт об изменениях)

$ git tag -a 1.2.1$ git checkout develop

Switched to branch 'develop'

$ git merge --no-ff hotfix-1.2.1

Merge made by recursive.

(Отчёт об изменениях). In this case, corrections will go into the development branch along with the entire release branch when it is closed. (Although, if working in develop requires an immediate bug fix and cannot wait for the current release to be completed, you can still patch the bugfix into the develop branch and it will be completely safe).

And finally, delete the temporary branch:

$ git branch -d hotfix-1.2.1

Deleted branch hotfix-1.2.1 (was abbe5d6).Conclusion

Although there is absolutely nothing fundamentally new in this branching model, the “big picture” with which this article begins has proved itself in our projects from the best side. It forms an elegant mental model, which is easy to fully capture with one glance, and which allows you to form a team's joint understanding of the branching and merging processes that are acting on the project.

The high quality PDF version of this image is free to download here . Print it and hang it on your wall so that it can be accessed at any time.

Note translator: the article is not new, the link to the original has already appeared on Habr. This translation is for those to whom English is still not so easy (as well as for my colleagues, among whom I am engaged in propaganda, hehe). To automate the procedures described in the article, the author created a gitflow project, which can be found on github .