Why lawyers do not agree on cryptocurrency

Legislative settlement of cryptocurrencies in Russia has been actively discussed since 2014, but no specific decision has yet been made. The Investigation Committee, the Prosecutor General’s Office and the Central Bank cautiously advised to refrain from using Bitcoins, but they did not take any concrete measures. The Ministry of Finance at some point prepared a prohibitive bill, but it was never submitted to the Duma. It seems that the authorities finally understood: it does not make sense to prohibit cryptocurrency.

However, if you do not prohibit cryptocurrency, then you need to legalize them - to determine the legal status (or, as the lawyers say, the legal regime). Why is this still not done and ( once again ) is it necessary to legalize cryptocurrencies at all?

Tl; dr: cryptocurrencies inevitably need to be legalized, but lawyers are terribly conservative creatures and do not like to invent new entities. Actually, therefore, cryptocurrencies in Russia still do not have a clear status: they cannot be equated to any of the existing objects of law.

1. Is legalization necessary at all?

Many believe that cryptocurrencies do not require legalization: they were created to minimize the costs of participants in the exchange, and drawing up contracts and signing papers - the same costs as, for example, transportation and recalculation of paper money. If cryptocurrencies are easy to transfer and impossible to take by force, should lawyers be allowed to them? Moreover, on the basis of the blockchain, you can construct smart contracts that are paid for with cryptocurrency - does this mean the final offensive of the “right end”?

Yes, smart contracts do in a certain sense replace the right, because they provide an alternative mechanism to protect the parties to the contract. With the help of a smart contract, we prescribe the conditions and guarantees of performance in the system itself, instead of turning to the huge greedy crowd of judges, notaries and lawyers. Of course, there are a number of problems associated with entering real-world data into the blockchain (oracles?), With network protection, with conditional transactions, etc .; but partly smart contracts do remove the need for legal processing of transactions.

However, if we take cryptocurrency transactions without smart contracts, then the risks of such transactions can be removed only legally. For example, the delivery of low-quality goods for cryptocurrency; translation of cryptocurrency under the influence of threat or fraud; translation of a cryptocurrency by an unauthorized subject or, say, to the wrong address - all this requires the intervention of a lawyer or at least an unbiased arbitrator, and consequently, the creation of some formal rules outside the blockchain. Here we go back to the right.

Without a clear definition of cryptocurrency is complicated by its use by bona fide entrepreneurs. How to withdraw money from the exchange to the account of the organization? How to register PI for mining on an industrial scale? How to exchange a cryptocurrency for a commodity - because while the cryptocurrency “does not exist”, legally it is a dummy, a vacuum; therefore, the exchange for it from a legal point of view would not be barter, but donation (which, I recall, is prohibited between commercial organizations).

It turns out that the legal regulation of cryptocurrency is needed not only by the state, but also by the system participants themselves. Legalization will lead a large business to cryptocurrencies, which will reduce the shadow market and whitewash the reputation of cryptocurrencies (primarily Bitcoin). Legalization will expand the use of cryptocurrencies as a means of exchange and payment: that is, cryptocurrencies will be more often used for non-investment purposes. This will increase the number of transactions and increase the decentralization of the corresponding blockchains.

OK, suppose that cryptocurrencies are ultimately legally resolved. The only question is how; and here the lawyers come to a standstill. Moreover, the problem cannot be solved by analogy with other countries because of the difference in legal systems (for example, the Russian and the American are very different).

2. Intangible assets and conservative lawyers The

Russian system of private law (to which applies, among other things, civil law, as well as the regulation of financial markets) is derived from the German one. Both for Russian and German law are characteristic: 1) extreme conservatism, reaching the point that new rules of law were allowed only to be derived from previous periods in some periods, and not created under actual relations; and 2) the tendency to pedantic systematization, on the basis of which the entire system of norms should be clearly laid out on the shelves without unnecessary details and prominent phenomena. I will demonstrate how these properties influenced the attitude of lawyers to tangible and intangible things.

By the beginning of the 19th century, German law, created on the basis of the systematization and processing of Roman law, was a coherent model:

This system functioned well as long as all things (including money) were material. But then everything changed, and the main revolution is associated with the emergence of copyright. Before mass printing, photography and other reproduction technologies, the authors did not need to protect the work: it was enough to protect its copy (for example, a picture, not an image on it), and since it was a thing, the task was reduced to a trivial one. Difficulties arose with the fall in prices for copying copies. The authors were unable to defend themselves against "pirates", since formally they did not violate any right. Attempts to adapt existing concepts to the problem, having recognized the author, for example, “the right of ownership to work,” were unsuccessful .

As a result of the legal revolution that lasted half a century, several international conventions introduced a new concept of exclusive rights (intellectual property). According to her, the author has the right to an intangible work; this right is expressed primarily in the right to prohibit the use of the work without the consent of the author. The work exists in the form of material originals, but is not tied to them.

In the future, the list of intellectual property added trademarks, industrial property (patents, utility models), the names of certain areas (Cognac, Champagne), and in the end even the source code.

In the 20th century, jurisprudence survived many more shocks — for example, the world was again seized by the concept of natural human rights. New intangible objects appeared in the circulation: non-cash money and intangible (non-documentary) securities. The need to store and transport to store volumes of fire-dangerous things led to the fact that the material money remained in the hands of citizens and in storage, and simple records on accounts began to be used in banks and on the stock exchange.

Since earlier these objects - both money and securities - were things, by analogy the same rules of law (for example, about the right of ownership) and the same remedies (claims) apply. In general, the new "intangible things" did not cause problems, because their turnover was carefully regulated. Banks took into account money in accounts, and publicly traded securities accounted for registrars in custody accounts; both those and those who were seriously responsible for the mistakes, and those and those were subject to state control, and only extreme force majeure like wars could cause confusion in the record.

As a result, by the end of the 20th century, in the law, the only intangible object settled in a special way was intellectual property. Money and stocks were settled more or less by analogy with things, and in controversial situations, banks and registrars were responsible for any mistakes.

3. Why are cryptocurrencies special?

Two factors give legal specificity to cryptocurrency. First, the storage of records about them is completely decentralized - unlike, for example, uncertificated securities. Secondly, the records on the availability of cryptocurrency on the account cannot be duplicated or copied, which distinguishes them from intellectual property objects (images, texts, etc.) As a result, we get an object of law that does not fit into the existing regulation at all.

Interestingly, this problem arose a bit earlier than cryptocurrency: a very similar dispute was caused by the sale of virtual items in MMORPG (purchased for real money). Such property is also intangible, and its copying is also technically limited (without the use of hacks). Players repeatedly filed such disputes with real courts, however, they received replies in reply: either that the dispute relates to the rules of the games (and is not subject to judicial review on the basis of article 1062 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation), or (for example, during failures or unjust bans of characters) that the games in the license agreement indicated a disclaimer (as is) and therefore acted within the framework of its right .

Now, when similar problems arise in the cryptocurrency turnover, it’s not so easy to get rid of the issue: we are not talking about games and there is no central node or licensing relations in the system.

But all sorts of payment operators are just not related to the problem of cryptocurrency. Both Yandex.Money and Webmoney are to a certain extent equated to banks, and e-wallets to current accounts. They do not create new objects, "electronic money": in fact, we are talking about ordinary rubles / dollars / etc. In the zero years, the payment system operators made a number of attempts to establish certain conventional units within the systems (for example, not rubles, but "cu" or "bonuses" were on the phone’s account, first of all so that the client could not remove units from the account (how to convert "bonuses" into rubles? No way). However, the state rather quickly banned the creation of money substitutes (the law “On the National Payment System”), and such tricks ended.

So, the state is faced with cryptocurrency as a qualitatively new phenomenon that needs to be somehow settled. The old legal mechanisms do not work; The old problem, which was fended off by the courts in disputes about virtual items in the MMORPG, is again coming to the fore in matters of cryptocurrency trading.

4. How to regulate?

If we consider the issue from a practical point of view, the state now has four options for regulation:

I will start with the last, fourth option: cryptocurrency as a new object of law .

Unfortunately, you should not count on a special, specially developed cryptocurrency regulation. This is primarily due to political reasons, not rational ones. The legal community is very conservative; New ideas are always accepted with hostility and used only if it is impossible to solve the problem with the help of existing means. It usually works for the good and protects our legal system from chaos, but there are exceptions. In the case of intellectual property, lawyers also resisted innovations for a long time - but there, as a result, several international conferences were convened under pressure from the right holders, at which they approved a uniform approach to intellectual property. So far, cryptocurrency has no influential lobbyists, and international relations are not the same ones to negotiate regulation at the level of entire continents.

There are purely Russian obstacles. The main rules relating to private law are collected in the Civil Code and several related laws. Our lawyers have already come to terms with the chaos in other areas (the law of Spring , the law on messengers , the law on the localization of personal data and similar odious things), but the Civil Code is protected from the last forces - a large ditch has been dug around it, so to speak, sandbags. The procedure for amending it is complicated to the limit, and on guard are the most experienced and most conservative representatives of the Council on the codification of civil law.

The emergence of a new object of law will require more than just point changes in the Civil Code - you will have to make a whole paragraph, if not a chapter. And considering that for every two lawyers there are three opinions, you can imagine how long it will take. Dmitry Anatolyevich wanted to quickly add to the Civil Code all the improvements that had accumulated in practice - and as a result, the reform was delayed for almost ten years. And in our case, of course, everyone is interested in resolving the issue as soon as possible.

Cryptocurrencies are easiest to equate to money . This solution seems simple to the obvious, because cryptocurrencies are used as a means of payment; By calling them “digital goods” or “things,” we are definitely wry.

Unfortunately, equating cryptocurrencies to money is even worse than inventing a new object of law. Since fiat (ordinary) money is the basis of the financial system, in law it manifested itself in millions of different places, and if we attribute cryptocurrency to money, then we will have to change a huge number of rules. That offhand first thing that comes to mind:

However, in addition to money, there is another similar intangible object: non-documentary securities. In Russia, stocks and bonds are issued in this form: they do not exist in reality and are stored as records in the register of a special organization - a registrar or a depositary. The shareholders themselves do not see their shares and do not hold them in their hands.

Unfortunately, under the new type of non-documentary securitiescryptocurrencies also do not fit. First, non-documentary papers under Russian law can only be issued during the issue. Who issues cryptocurrency is not clear (miners? Blockchain developer? End users?), Which means it is not clear who will be responsible for violations at this stage. Of course, if we want to settle the ICO procedure, in the future it is worth settling “cryptoemission” at the level of legislation, but so far there is no such question (despite the entire HYIP).

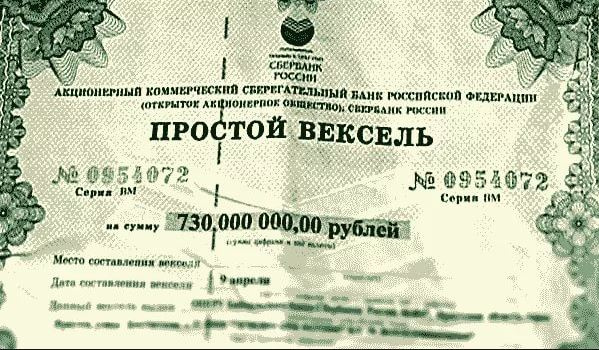

You can recall, of course, about such a mossy category as bearer securities - like a bill that can be issued without specifying the holder: “Romashka LLC from Moscow undertakes to issue a million rubles to the bearer of this paper”. Bearer papers have always been documentary (guess why), but in the case of cryptocurrencies we could surprise the whole world with the birth of a new chimerical phenomenon: uncertificated bearer paper. From my point of view, this sounds very fun, but the older generation is unlikely to appreciate it.

There are also purely legal obstacles to classifying cryptocurrencies as securities. For example, a security, unlike cryptocurrency, cannot endlessly share: no matter how we divide our package, sooner or later we will reach a certain minimum amount of securities that cannot be divided into parts. The security also establishes the rights to something: to pay interest (a bond), to manage a firm and receive dividends (a share), and so on. Cryptocurrency does not establish anything and in this respect it does not resemble a security. Cryptocurrency can actually be destroyed (by sending to a non-existent wallet), and non-documentary paper can not be destroyed under any circumstances. And so on.

In general, cryptocurrencies can be equated to securities, but this will require major changes in financial legislation. Perhaps in the future, when ICO needs to be settled, the state will pay attention to this; in the meantime, this option will require too much effort.

5. Compromise option

In essence, the only remaining option is to equate cryptocurrency with propertyand regulate its turnover by analogy with material things. This, of course, is not ideal, but in the present conditions - the most optimal. Fortunately, the list of objects of civil law in the Civil Code is not limited and ends with a meaningful phrase “other property” to which everything can be referred. Cryptocurrency will be subject to ownership; It sounds, of course, a bit absurd, but what to do - as I said, is a compromise.

The status of the property means that it will be possible to buy, sell and exchange cryptocurrencies, like any other objects of property rights. It will be possible not to worry about exactly where - in Russia or abroad - the counterparty is located (it is important considering the distribution of the blockchain).

If cryptocurrencies are not classified as goods, there will be no tax issues - such as paying VAT when selling cryptocurrencies or applying advertising legislation to cryptocurrencies. In fact, in this case, cryptocurrency as an investment instrument will be settled as loyally as possible, since, unlike securities, “other assets” will impose on miners and owners much less obligations. Moreover, organizations will be able to put cryptocurrencies on the balance (after the Ministry of Finance explains to them exactly how to do it).

In an amicable way, it would still be good to include an article on cryptocurrency in the Civil Code, since all other “special” objects of property rights (real estate, money, animals, etc.) are separate articles. On the other hand, most likely, the legislator will not strain, but will act as “information”, about which they simply wrote in the relevant law: the information, they say, is the object of civil legal relations (and figure it out in what capacity it is put into circulation).

Of course, individual issues, primarily of practical nature, will remain open. For example, most cryptocurrencies involve the unambiguous addressing of wallets and their owners; This means that in relation to the protection of the rights to such cryptocurrencies, a lawsuit must be filed for recovery from other people's illegal possession (vindication). If the cryptocurrency goes to the wrong destination or is stolen from the wallet, its rightful owner can always ask the court to oblige the actual owner to return it. At the same time, in practice such a decision will be unenforceable: it is clear that no bailiffs can force a return of a cryptocurrency if the purse owner does not want this.

Also a big question will still be connected with mining - it may have to be resolved separately. While cryptocurrencies are a legal “empty place”, miners have nothing to pay taxes for; I would say that mining is a great way to understate profits within a company. Therefore, one way or another, mining at legal entities will fall into legislation, albeit formally, with a zero VAT rate on the resulting assets. For lawyers, the question is something else: since cryptocurrency is a property, then to which way of occurrence of rights to it is mining? “Turning into the property of publicly accessible things” is best suited (if you consider hashes to be “publicly available things”), but the question itself, of course, looks schizophrenic. Can there really be a property right to a number?

I am sure that you can think up a lot of other strange examples, to which the equalization of cryptocurrency to property will lead - like the instructions provided by officials in property tax declarations (“bitcoins. 100 pieces”). If you have read this far, throw your own variants of strange and unforeseen consequences into the comments, which the “property” approach to cryptocurrency will lead to.

Well, the official disclaimer: this article is only the fruit of my thoughts and you should not draw conclusions about any future legal regulation on it. While there are no official statements, the regulation of cryptocurrency may be very different, and legislators may have arguments that I underestimated or did not take into account. So while the question raised in the article - rather a legal charge for the mind.

However, if you do not prohibit cryptocurrency, then you need to legalize them - to determine the legal status (or, as the lawyers say, the legal regime). Why is this still not done and ( once again ) is it necessary to legalize cryptocurrencies at all?

Tl; dr: cryptocurrencies inevitably need to be legalized, but lawyers are terribly conservative creatures and do not like to invent new entities. Actually, therefore, cryptocurrencies in Russia still do not have a clear status: they cannot be equated to any of the existing objects of law.

1. Is legalization necessary at all?

Many believe that cryptocurrencies do not require legalization: they were created to minimize the costs of participants in the exchange, and drawing up contracts and signing papers - the same costs as, for example, transportation and recalculation of paper money. If cryptocurrencies are easy to transfer and impossible to take by force, should lawyers be allowed to them? Moreover, on the basis of the blockchain, you can construct smart contracts that are paid for with cryptocurrency - does this mean the final offensive of the “right end”?

Yes, smart contracts do in a certain sense replace the right, because they provide an alternative mechanism to protect the parties to the contract. With the help of a smart contract, we prescribe the conditions and guarantees of performance in the system itself, instead of turning to the huge greedy crowd of judges, notaries and lawyers. Of course, there are a number of problems associated with entering real-world data into the blockchain (oracles?), With network protection, with conditional transactions, etc .; but partly smart contracts do remove the need for legal processing of transactions.

However, if we take cryptocurrency transactions without smart contracts, then the risks of such transactions can be removed only legally. For example, the delivery of low-quality goods for cryptocurrency; translation of cryptocurrency under the influence of threat or fraud; translation of a cryptocurrency by an unauthorized subject or, say, to the wrong address - all this requires the intervention of a lawyer or at least an unbiased arbitrator, and consequently, the creation of some formal rules outside the blockchain. Here we go back to the right.

Without a clear definition of cryptocurrency is complicated by its use by bona fide entrepreneurs. How to withdraw money from the exchange to the account of the organization? How to register PI for mining on an industrial scale? How to exchange a cryptocurrency for a commodity - because while the cryptocurrency “does not exist”, legally it is a dummy, a vacuum; therefore, the exchange for it from a legal point of view would not be barter, but donation (which, I recall, is prohibited between commercial organizations).

It turns out that the legal regulation of cryptocurrency is needed not only by the state, but also by the system participants themselves. Legalization will lead a large business to cryptocurrencies, which will reduce the shadow market and whitewash the reputation of cryptocurrencies (primarily Bitcoin). Legalization will expand the use of cryptocurrencies as a means of exchange and payment: that is, cryptocurrencies will be more often used for non-investment purposes. This will increase the number of transactions and increase the decentralization of the corresponding blockchains.

OK, suppose that cryptocurrencies are ultimately legally resolved. The only question is how; and here the lawyers come to a standstill. Moreover, the problem cannot be solved by analogy with other countries because of the difference in legal systems (for example, the Russian and the American are very different).

2. Intangible assets and conservative lawyers The

Russian system of private law (to which applies, among other things, civil law, as well as the regulation of financial markets) is derived from the German one. Both for Russian and German law are characteristic: 1) extreme conservatism, reaching the point that new rules of law were allowed only to be derived from previous periods in some periods, and not created under actual relations; and 2) the tendency to pedantic systematization, on the basis of which the entire system of norms should be clearly laid out on the shelves without unnecessary details and prominent phenomena. I will demonstrate how these properties influenced the attitude of lawyers to tangible and intangible things.

By the beginning of the 19th century, German law, created on the basis of the systematization and processing of Roman law, was a coherent model:

- All material objects were things that were divided into many categories: movable and immovable, individually-defined things and generic, divisible and indivisible, animate (animals) and inanimate, etc.

- The rights to things owned by persons - subjects of law. They are divided into individuals (people) and legal (organizations), which are also divided into many types.

- For persons recognized the rights to things. This means that it does not matter who actually possesses the thing: it is important to have the right (on the basis of law or a contract) to this thing - the so-called subjective right. For example, one of the types of subjective rights is the right of ownership. If I own item X, then even if someone takes possession of them against my will, I can go to court with the demand (claim) and force the violator to return the wallet: after all, I have the right to the wallet, not him.

This system functioned well as long as all things (including money) were material. But then everything changed, and the main revolution is associated with the emergence of copyright. Before mass printing, photography and other reproduction technologies, the authors did not need to protect the work: it was enough to protect its copy (for example, a picture, not an image on it), and since it was a thing, the task was reduced to a trivial one. Difficulties arose with the fall in prices for copying copies. The authors were unable to defend themselves against "pirates", since formally they did not violate any right. Attempts to adapt existing concepts to the problem, having recognized the author, for example, “the right of ownership to work,” were unsuccessful .

As a result of the legal revolution that lasted half a century, several international conventions introduced a new concept of exclusive rights (intellectual property). According to her, the author has the right to an intangible work; this right is expressed primarily in the right to prohibit the use of the work without the consent of the author. The work exists in the form of material originals, but is not tied to them.

In the future, the list of intellectual property added trademarks, industrial property (patents, utility models), the names of certain areas (Cognac, Champagne), and in the end even the source code.

In the 20th century, jurisprudence survived many more shocks — for example, the world was again seized by the concept of natural human rights. New intangible objects appeared in the circulation: non-cash money and intangible (non-documentary) securities. The need to store and transport to store volumes of fire-dangerous things led to the fact that the material money remained in the hands of citizens and in storage, and simple records on accounts began to be used in banks and on the stock exchange.

Since earlier these objects - both money and securities - were things, by analogy the same rules of law (for example, about the right of ownership) and the same remedies (claims) apply. In general, the new "intangible things" did not cause problems, because their turnover was carefully regulated. Banks took into account money in accounts, and publicly traded securities accounted for registrars in custody accounts; both those and those who were seriously responsible for the mistakes, and those and those were subject to state control, and only extreme force majeure like wars could cause confusion in the record.

As a result, by the end of the 20th century, in the law, the only intangible object settled in a special way was intellectual property. Money and stocks were settled more or less by analogy with things, and in controversial situations, banks and registrars were responsible for any mistakes.

3. Why are cryptocurrencies special?

Two factors give legal specificity to cryptocurrency. First, the storage of records about them is completely decentralized - unlike, for example, uncertificated securities. Secondly, the records on the availability of cryptocurrency on the account cannot be duplicated or copied, which distinguishes them from intellectual property objects (images, texts, etc.) As a result, we get an object of law that does not fit into the existing regulation at all.

Interestingly, this problem arose a bit earlier than cryptocurrency: a very similar dispute was caused by the sale of virtual items in MMORPG (purchased for real money). Such property is also intangible, and its copying is also technically limited (without the use of hacks). Players repeatedly filed such disputes with real courts, however, they received replies in reply: either that the dispute relates to the rules of the games (and is not subject to judicial review on the basis of article 1062 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation), or (for example, during failures or unjust bans of characters) that the games in the license agreement indicated a disclaimer (as is) and therefore acted within the framework of its right .

Now, when similar problems arise in the cryptocurrency turnover, it’s not so easy to get rid of the issue: we are not talking about games and there is no central node or licensing relations in the system.

But all sorts of payment operators are just not related to the problem of cryptocurrency. Both Yandex.Money and Webmoney are to a certain extent equated to banks, and e-wallets to current accounts. They do not create new objects, "electronic money": in fact, we are talking about ordinary rubles / dollars / etc. In the zero years, the payment system operators made a number of attempts to establish certain conventional units within the systems (for example, not rubles, but "cu" or "bonuses" were on the phone’s account, first of all so that the client could not remove units from the account (how to convert "bonuses" into rubles? No way). However, the state rather quickly banned the creation of money substitutes (the law “On the National Payment System”), and such tricks ended.

So, the state is faced with cryptocurrency as a qualitatively new phenomenon that needs to be somehow settled. The old legal mechanisms do not work; The old problem, which was fended off by the courts in disputes about virtual items in the MMORPG, is again coming to the fore in matters of cryptocurrency trading.

4. How to regulate?

If we consider the issue from a practical point of view, the state now has four options for regulation:

- Equate cryptocurrency to a generally accepted currency (to fiat money);

- Equate cryptocurrency to securities;

- Equate cryptocurrency to material things (goods);

- Come up with a new regulation, the most suitable for cryptocurrency.

I will start with the last, fourth option: cryptocurrency as a new object of law .

Unfortunately, you should not count on a special, specially developed cryptocurrency regulation. This is primarily due to political reasons, not rational ones. The legal community is very conservative; New ideas are always accepted with hostility and used only if it is impossible to solve the problem with the help of existing means. It usually works for the good and protects our legal system from chaos, but there are exceptions. In the case of intellectual property, lawyers also resisted innovations for a long time - but there, as a result, several international conferences were convened under pressure from the right holders, at which they approved a uniform approach to intellectual property. So far, cryptocurrency has no influential lobbyists, and international relations are not the same ones to negotiate regulation at the level of entire continents.

There are purely Russian obstacles. The main rules relating to private law are collected in the Civil Code and several related laws. Our lawyers have already come to terms with the chaos in other areas (the law of Spring , the law on messengers , the law on the localization of personal data and similar odious things), but the Civil Code is protected from the last forces - a large ditch has been dug around it, so to speak, sandbags. The procedure for amending it is complicated to the limit, and on guard are the most experienced and most conservative representatives of the Council on the codification of civil law.

The emergence of a new object of law will require more than just point changes in the Civil Code - you will have to make a whole paragraph, if not a chapter. And considering that for every two lawyers there are three opinions, you can imagine how long it will take. Dmitry Anatolyevich wanted to quickly add to the Civil Code all the improvements that had accumulated in practice - and as a result, the reform was delayed for almost ten years. And in our case, of course, everyone is interested in resolving the issue as soon as possible.

Cryptocurrencies are easiest to equate to money . This solution seems simple to the obvious, because cryptocurrencies are used as a means of payment; By calling them “digital goods” or “things,” we are definitely wry.

Unfortunately, equating cryptocurrencies to money is even worse than inventing a new object of law. Since fiat (ordinary) money is the basis of the financial system, in law it manifested itself in millions of different places, and if we attribute cryptocurrency to money, then we will have to change a huge number of rules. That offhand first thing that comes to mind:

- Our legislation even in theory does not provide that money can be issued not by the state (or a collective entity - such as the ECU or the euro). Accordingly, any currency has a country of origin; Foreign and national currencies are settled differently, and so on. How cryptocurrency will fit into this system is not yet clear.

- Currency turnover is subject to currency control: you cannot conduct transactions in foreign currency (non-rubles) within the country, and also withdraw currency from the country without some formal documents (bank notification, transaction passport, etc.) If this does not apply to cryptocurrency , currency control, in essence, will become meaningless. If distributed, it is not clear how it will be implemented, since banks (the main agents of currency control) do not have access to wallets.

- The exchange of cryptocurrencies for rubles will require the creation of an interbank market for operations with cryptocurrencies, and, possibly, the official rate of the Central Bank for some coins (lol).

However, in addition to money, there is another similar intangible object: non-documentary securities. In Russia, stocks and bonds are issued in this form: they do not exist in reality and are stored as records in the register of a special organization - a registrar or a depositary. The shareholders themselves do not see their shares and do not hold them in their hands.

Unfortunately, under the new type of non-documentary securitiescryptocurrencies also do not fit. First, non-documentary papers under Russian law can only be issued during the issue. Who issues cryptocurrency is not clear (miners? Blockchain developer? End users?), Which means it is not clear who will be responsible for violations at this stage. Of course, if we want to settle the ICO procedure, in the future it is worth settling “cryptoemission” at the level of legislation, but so far there is no such question (despite the entire HYIP).

You can recall, of course, about such a mossy category as bearer securities - like a bill that can be issued without specifying the holder: “Romashka LLC from Moscow undertakes to issue a million rubles to the bearer of this paper”. Bearer papers have always been documentary (guess why), but in the case of cryptocurrencies we could surprise the whole world with the birth of a new chimerical phenomenon: uncertificated bearer paper. From my point of view, this sounds very fun, but the older generation is unlikely to appreciate it.

There are also purely legal obstacles to classifying cryptocurrencies as securities. For example, a security, unlike cryptocurrency, cannot endlessly share: no matter how we divide our package, sooner or later we will reach a certain minimum amount of securities that cannot be divided into parts. The security also establishes the rights to something: to pay interest (a bond), to manage a firm and receive dividends (a share), and so on. Cryptocurrency does not establish anything and in this respect it does not resemble a security. Cryptocurrency can actually be destroyed (by sending to a non-existent wallet), and non-documentary paper can not be destroyed under any circumstances. And so on.

In general, cryptocurrencies can be equated to securities, but this will require major changes in financial legislation. Perhaps in the future, when ICO needs to be settled, the state will pay attention to this; in the meantime, this option will require too much effort.

5. Compromise option

In essence, the only remaining option is to equate cryptocurrency with propertyand regulate its turnover by analogy with material things. This, of course, is not ideal, but in the present conditions - the most optimal. Fortunately, the list of objects of civil law in the Civil Code is not limited and ends with a meaningful phrase “other property” to which everything can be referred. Cryptocurrency will be subject to ownership; It sounds, of course, a bit absurd, but what to do - as I said, is a compromise.

The status of the property means that it will be possible to buy, sell and exchange cryptocurrencies, like any other objects of property rights. It will be possible not to worry about exactly where - in Russia or abroad - the counterparty is located (it is important considering the distribution of the blockchain).

If cryptocurrencies are not classified as goods, there will be no tax issues - such as paying VAT when selling cryptocurrencies or applying advertising legislation to cryptocurrencies. In fact, in this case, cryptocurrency as an investment instrument will be settled as loyally as possible, since, unlike securities, “other assets” will impose on miners and owners much less obligations. Moreover, organizations will be able to put cryptocurrencies on the balance (after the Ministry of Finance explains to them exactly how to do it).

In an amicable way, it would still be good to include an article on cryptocurrency in the Civil Code, since all other “special” objects of property rights (real estate, money, animals, etc.) are separate articles. On the other hand, most likely, the legislator will not strain, but will act as “information”, about which they simply wrote in the relevant law: the information, they say, is the object of civil legal relations (and figure it out in what capacity it is put into circulation).

Of course, individual issues, primarily of practical nature, will remain open. For example, most cryptocurrencies involve the unambiguous addressing of wallets and their owners; This means that in relation to the protection of the rights to such cryptocurrencies, a lawsuit must be filed for recovery from other people's illegal possession (vindication). If the cryptocurrency goes to the wrong destination or is stolen from the wallet, its rightful owner can always ask the court to oblige the actual owner to return it. At the same time, in practice such a decision will be unenforceable: it is clear that no bailiffs can force a return of a cryptocurrency if the purse owner does not want this.

Also a big question will still be connected with mining - it may have to be resolved separately. While cryptocurrencies are a legal “empty place”, miners have nothing to pay taxes for; I would say that mining is a great way to understate profits within a company. Therefore, one way or another, mining at legal entities will fall into legislation, albeit formally, with a zero VAT rate on the resulting assets. For lawyers, the question is something else: since cryptocurrency is a property, then to which way of occurrence of rights to it is mining? “Turning into the property of publicly accessible things” is best suited (if you consider hashes to be “publicly available things”), but the question itself, of course, looks schizophrenic. Can there really be a property right to a number?

I am sure that you can think up a lot of other strange examples, to which the equalization of cryptocurrency to property will lead - like the instructions provided by officials in property tax declarations (“bitcoins. 100 pieces”). If you have read this far, throw your own variants of strange and unforeseen consequences into the comments, which the “property” approach to cryptocurrency will lead to.

Well, the official disclaimer: this article is only the fruit of my thoughts and you should not draw conclusions about any future legal regulation on it. While there are no official statements, the regulation of cryptocurrency may be very different, and legislators may have arguments that I underestimated or did not take into account. So while the question raised in the article - rather a legal charge for the mind.