Derivatives on carrots

Derivatives are derivative financial instruments. They are derivatives because they are based on some other asset. Derivatives themselves are dummies, their value is determined by the price of the underlying asset - the product, security, currency, debt - that is, from which they are derived.

Derivatives are derivative financial instruments. They are derivatives because they are based on some other asset. Derivatives themselves are dummies, their value is determined by the price of the underlying asset - the product, security, currency, debt - that is, from which they are derived. What are derivatives used for? Their first purpose is to hedge risks, that is, redistribution of risk, safety net. All derivatives transactions are facing the future. The safety net is that you freeze a certain, already familiar and, in principle, situation that you like today in order to apply it in an unreliable tomorrow.

The second value of derivatives is a speculation tool.

The main types of derivatives are:

- forwards (futures);

- options;

- swaps.

Forward - make sure

Imagine that I am a manufacturer. "Lizka Carrot Enterprise." I produce carrots. Now, conditionally, in March, I spend sowing. Prices - well, let it be 60 rubles per kilogram of carrots. I like this price: I cover my expenses, I even get a little profit. But now the crisis is around, and I don’t know what will happen in August, when I will harvest and set out to sell my wonderful carrot. The price can be 70 rubles per kilo - and I will benefit. The price may be 50 rubles per kilo - and I am much loser. Well, I agree not to get 70 rubles, which do not necessarily shine for me, but to definitely get my 60 rubles, which suits me. Just not to get only 50, for which I will not live.

Therefore, I am looking for some little man who is already now, in March, interested in buying carrots from me in August. Let's say it will be Lena Rabbit Production. Massively bred rabbits. Lena also does not know what will happen in August. If the price in August is 50 rubles per kg of carrots, she will buy more carrots for rabbits, they will grow fat, give a lot of valuable fur and 3-4 kg of dietary meat. If the price is 70 rubles per kg of carrots, then Lena will not buy a lot of carrots and half of the rabbits will die a terrible starvation. But if the price is 60 rubles per kg of carrots - this is normal.

Hooray, we found each other. Our interests coincided. I agree to sell my carrot in August for 60 rubles, and Lena agree to buy my carrot for 60 rubles. We both realize that maybe in August one of us could conclude an agreement on the best terms for ourselves. But we are also aware that someone could have entered into an agreement in August on much worse terms. Nobody wants to lose a lot. So, in March we conclude a forward contract in order to be safe from the August risks. Item and payment will also be transferred in August.

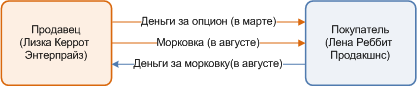

In the cubes and arrows, what we agreed on looks like this:

On direct time, the whole agreement looks like this:

There are forward and non-deliverable forwards. A delivery forward is an example above - when a producer (in this case, the seller better illustrates this) really hedges his risks and really then transfers a very real carrot.

A non-deliverable forward is purely a speculation tool. There are no producers of real carrots, no carrots are transmitted anywhere. You can, for example, make a non-deliverable forward in a currency. In this case, in March I will conclude with Lena an agreement that in August I will sell her 1 dollar for 24 rubles. And I will have to sell her in August 1 dollar for 24 rubles. And if in August 1 dollar will cost 76 rubles, then guess which one of us screwed up and got less forward than he could without, and who won, and got more forward than he could without.

For starters : what's the difference between forward and futures? Yes, no. Only futures is a forward traded on an exchange. A forward is futures, but outside the exchange.

Option - choose

An option is an advanced form of forward. I'm still the same Lizka Carrot Enterprise, which produces carrots. And this time, having broken my teeth on unsuccessful forwards, I think: “Why should I conclude an agreement in August, when the market price (70 rubles) can be much more convenient for me than for a forward (60 rubles)?

Then I go, look for Lena and offer her a new, improved forward. I invite her today in March to conclude an agreement that in August I, of my choice, will sell or not sell her carrots for 60 rubles. My choice will depend on what the price of carrots is in the market.

But Lena is also not a miss. What is this: I will choose whether to sell to me or not, and Lenka will depend entirely on my decision? Therefore, she also hedges her risks. For the opportunity to choose whether to sell or not to sell, I pay Lena money back in March, which will cover her lost profit if I still decide not to sell. Thus, in March I buy from Len an option to sell carrots in August.

If in August I choose to sell, then in the square-arrow form it all looks like this:

If in August I choose not to sell, then in the square-arrow form, it looks like this (the dotted lines indicate the options included in the option):

On the line time all our actions are as follows:

An inquisitive reader must have noticed that the number of arrows from me to Lena and from Lena to me in the first diagram does not match: I have a lot more. Twice. Right. And all because you have to pay for the pleasure of patting your nerves. Moreover, this ensures the interests of Lena: I already give her money today, which means that the less likely that I will throw her tomorrow.

For a snack: there are put options, there are call options. Put option - I choose to sell or not to sell (remember this: “I put to the market”). This is similar to the example considered. Call option - I choose to buy or not to buy (remember this: “I call from the market.” Stupidly, but associatively). This is the opposite of the case considered above. Here Lena, the buyer, pays me, the seller, money in March for the opportunity to choose in August whether to buy or not to buy. And the rest is the same.

Swap - change

Even cooler. We continue to evolve.

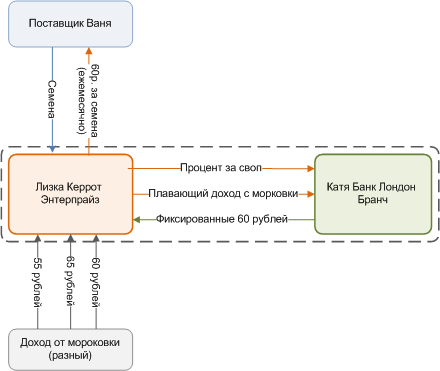

I'm still Lizka Carrot Enterprise, still producing carrots. For the production of carrots, I buy seeds from some Vanya. I pay stably, always 60 rubles a month. And my carrot production brings me either 55, then 50, then 60, then 70, or 65. In general, I have fixed costs, and my income is floating.

I, in principle, are satisfied when a carrot brings me an income of 60 rubles - this covers my expenses for seeds. But when carrots bring 55 or 50, it’s bad. When a carrot brings 70 rubles - this is very good, but it would be better if she always brought me 60, then it is thick, then empty.

And then I go and look for someone who will help me make sure that I always have 60, and sometimes it’s either thick or empty. Let’s leave Lena alone, we have already patted her nerves. Find someone new, such as Katya Bank London Branch.

I suggest that Katya give her her floating income from carrots in exchange for her regular payments to me in the amount of 60 rubles.

Let’s turn to the boxes and arrows that I love so much (the dotted line indicates the relationships included in the swap):

It can be the other way round, when my income is stable and my expense (or debt payments) is floating. I can change anything floating on anything fixed and vice versa. How it works in the market. Usually there are more than two participants. Often one needs to exchange floating

the bet is fixed, and the other needs to change fixed to floating. In this case, they find an intermediary (all the same "Katya Bank"), which, however, actively takes interest on their services.

Let's move on to the boxes and arrows. The dotted line is one swap relationship. The colored dotted line is how inside Katya Bank the money of one client goes to serve another client.

For a snack, we’ll sort the repo - like a thing very similar to swaps.

Repo - round-trip

Here you will have to change the scope of activity a little and operate not with carrots, but with stocks, because repos are held with securities. But, by the way, you can imagine stocks in the form of carrots, if so clearly.

That means I have stocks. Well, I have and have. But human greed knows no bounds, and now I think how to attach them in such a way as to not only dividends and management in the company, but also to raise some left money. Moreover, I need to raise the left money right now (well, the carrot mafia is twisting my arms), and then someday I, in principle, agree to lose. But I need a jackpot now.

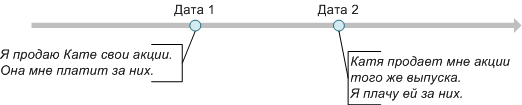

Then I go to Katya and offer her the following: I sell you (yes, ownership, absolutely ownership) my shares for a reasonable price, and then you sell me the same shares back and also to the property. Not necessarily the same ones. The main thing is the same issue.

That is, this is one operation consisting of two transactions - selling there and selling back. The dough cycle in nature.

First space-time continuum:

Now the squares and arrows:

Note that since I transfer the shares to Kate, she can do anything with them: receive dividends, sell, etc. At the same time, according to English law, I can conclude an agreement with Katya that she will vote on my instructions, and that even the people to whom she may sell my shares will also vote on my instructions. You can conclude that all dividends (well, minus interest) go to me.

Thus, it turns out that having lost ownership of the shares, I retain all the positive aspects of the stock holding, including the dividend money. At the same time, on Date 1 I get an extra jackpot - a stock purchase fee, which I need exactly on Date 1. But on Date 2 I lose this jackpot because I already pay for the purchase of Katya's shares. But this is not scary, since I needed left money in Date 1.

In addition, given that I sell shares in Date 1, when the price was one, and buy on Date 2, when the price is different, I can perfectly play on it.

I hope it was interesting and understandable.

Lisa Romanova