Ask Ethan: Why do so many objects collide with Jupiter?

- Transfer

Chelyabinsk meteorite; photo: Konstantin Kudinov

One of the most interesting and at the same time scary events taking place on Earth is a collision with a fragment of a comet or an asteroid. Collisions like what happened not so long ago in Chelyabinsk are quite frequent; during the life of a person can see many such objects. Much less often there are collisions, leading to such consequences as the case of Tunguska, the Arizona crater or the Great Extinction, which happened 65 million years ago. The results of such collisions are still visible. But they cannot be compared with what Jupiter is experiencing. Why? Dominic Turpin asks:

So many space objects crash into Jupiter because of its gravity force, or because it is too big to miss it?

When, on March 17, 2016, amateur astronomers Gerrit Kernbauer and John Makeon randomly observed and filmed the largest world of our solar system, a sudden flash occurred on it.

The only known cause of such flares is collisions, and recently we have seen a large number of collisions with Jupiter, mainly due to amateur astronomers who like to look at it even while professional telescopes are not aimed at the planet. And over the past few years, amateurs have been able to detect a large number of collisions, including:

In June 1994, Comet Shoemakers-Levy 9 fell apart and collided with Jupiter. Thanks to our knowledge of gravity, this event was predicted in a year. Because of this collision, the surface of Jupiter darkened for months. The diameter of the comet before the collapse was about 5 km.

In July 2009, amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley discovered a dark spot the size of Earth on Jupiter. Most likely, it was the result of a collision with an asteroid with a diameter of 0.2 - 0.5 km. Subsequent observations of the space telescope. Hubble (in the optical range, above) and the Keck Observatory telescope (in the infrared range, below) showed that the collision produced a thousand times more energy than on Tunguska.

In June 2010, another collision was recorded, and in real time. He was again seen by Anthony Wesley and Christopher Guo from the Philippines. The outbreak lasted two seconds, which corresponds to a mass of about 500 - 2000 tons and a size of 8-13 m. According to data from the Gemini Observatory, on Jupiter, most likely, such objects fall several times a year.

A few months later, in August of 2010, another collision occurred (higher) on Jupiter, which led to a small flash. He was discovered by another amateur, Masayuki Tachikawa from Japan. In September 2012, Dan Petersen observed another outbreak on Jupiter, and this time George Hall filmed a video of the event, which allowed scientists to determine: the collision in size and power roughly coincided with the collision in August 2010. Why does this happen on Jupiter? Why do such large, bright and frequent collisions happen there, compared to which the largest of the collisions that we have seen on Earth fade away? Of course, first of all the size comes to mind. To calculate the collision frequency in any system, the simplest estimate is to multiply:

1. velocities of objects (comets, asteroids, meteors),

2. concentration of objects in the volume,

3. cross section of a potential target.

The speeds of comets and asteroids flying near Jupiter practically coincide with the speeds of objects near the Earth, and their concentration in a certain volume is about the same, although Jupiter has a slight advantage due to the fact that it is slightly closer to the asteroid belt. But the cross section is very different: the diameter of Jupiter is 11.2 times the diameter of the Earth, which means that its cross section is 125 times larger.

Yet the frequency of major collisions cannot be explained. The clash of 2009 occurred with a larger object than the one that left the Arizona crater, and such collisions on Earth occur approximately every 30,000–100,000 years. But the fact that we saw the collision of such power on Jupiter less than ten years ago - and the collision of Shoemakers-Levy only 15 years before - makes us accept the unpleasant fact: if such large objects would bombard the Earth as often as Jupiter, we would have seen 10-100 times more Arizona-type craters, and extinctions would have happened thousands of times more often!

The asteroid that “killed the dinosaurs” had a diameter of 5-10 km and collided with the Earth 65 million years ago. On the other hand, comet Shoemakers-Levy 9 collided with Jupiter in 1994, and had the same size. Well, it turns out that in 1994 we witnessed an event that happens every 500,000 years? Very unlikely.

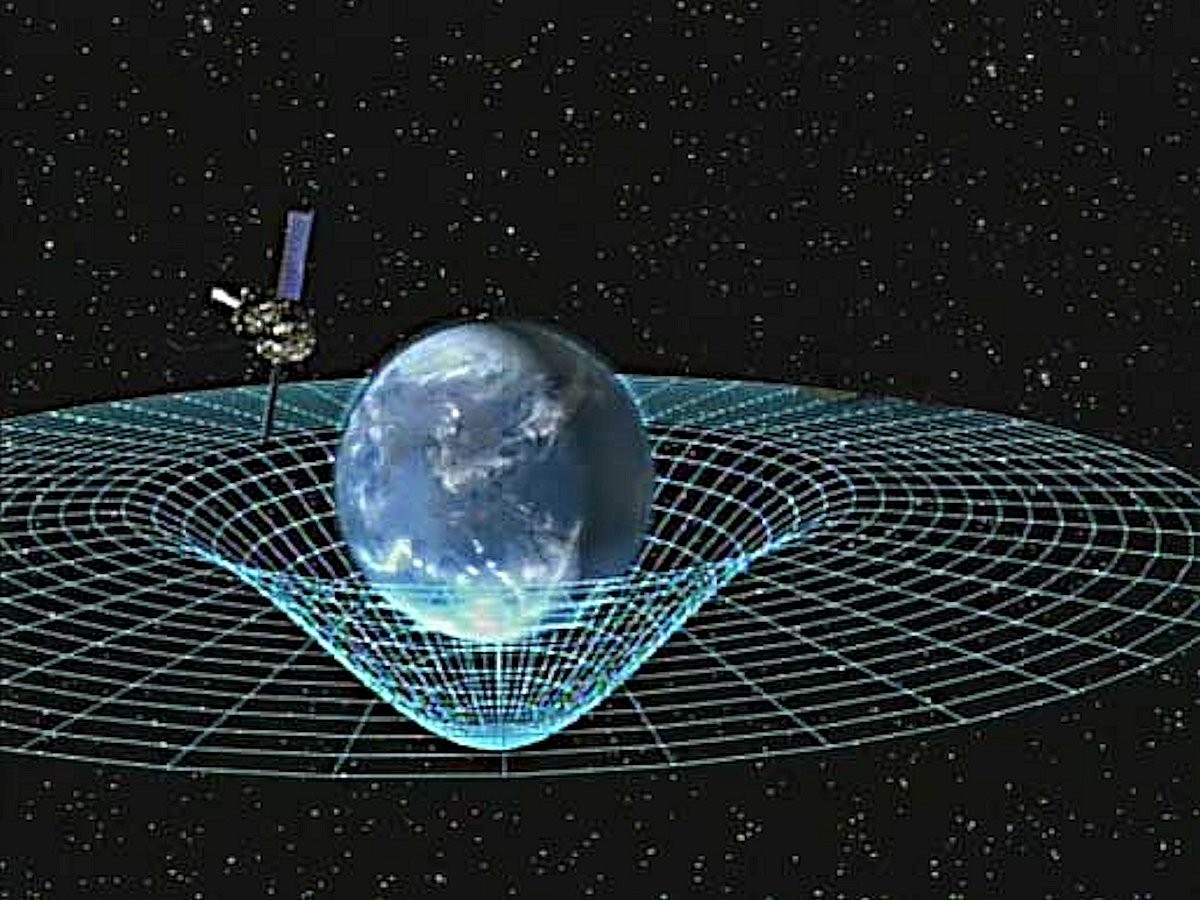

Consider better another characteristic of Jupiter: gravity. Planets do not just sit in space and wait for something to crash into them. They deform the very fabric of space-time in direct proportion to its mass. The more massive the planet, the stronger its gravitational attraction, acting on all the surrounding and passing masses.

Earth's gravitational field is rather weak. If a slow moving object passes by us - less than 10 km / s relative to us - we will cope in order to pull it towards us. But asteroids usually move at relative speeds of 17 km / s or more, and comets are faster than 50 km / s. In other words, our gravity is not capable of anything.

Jupiter is 317 times heavier, and even with its huge radius it copes well with attracting objects moving at a relative speed of 50 km / s. In other words, almost all objects that fall in its vicinity.

Yes, Jupiter is larger than Earth, and its size is to blame for an increase in the number of collisions by about 100 times. But in fact, collisions with Jupiter occur more often due to its gravitational attraction, which attracts a huge number of comets and asteroids too close to it - which the Earth is incapable of. It's all about the combination of gravity and the fact that objects farther from the Sun — even fast comets — move more slowly, so they are easier to capture.

Size does matter, but not like gravity. The only object that best attracts asteroids in the solar system is the Sun itself, but Jupiter is firmly in second place. The leading theory said that it protects the insides of the solar system from asteroid attacks - but it turned out that it was not. He just went well with the role of a whipping machine. For the rest, we have to rely on ourselves.