The Lurk virus hacked banks while it was written by ordinary hired workers

Excerpt from the book “Invasion. A Brief History of Russian Hackers

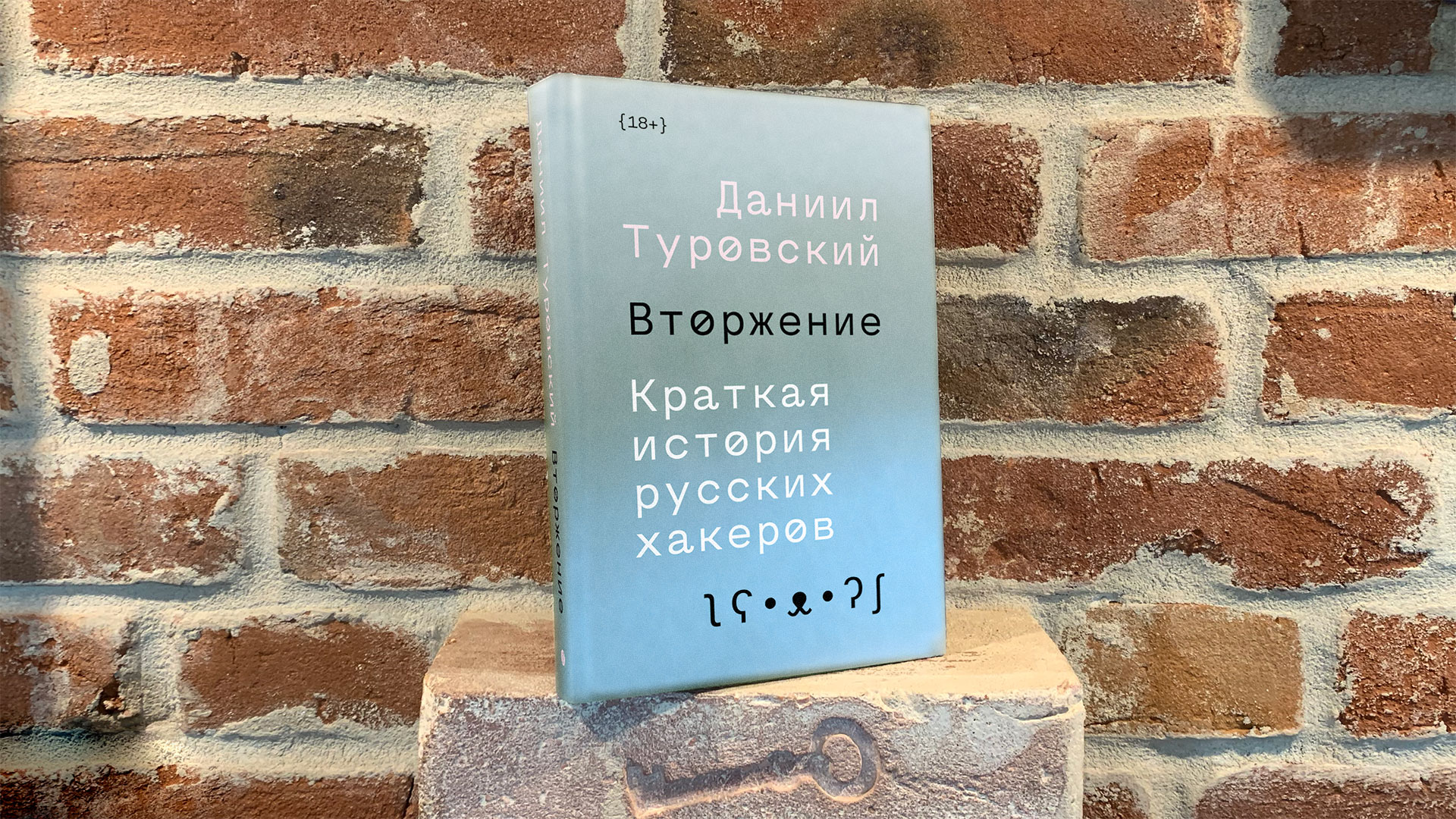

In May of this year , the book by journalist Daniil Turovsky, “Invasion. A brief history of Russian hackers. " It contains stories from the dark side of the Russian IT industry - about the guys who fell in love with computers and learned not just to program, but to rob people. The book is developing, like the phenomenon itself - from teenage hooliganism and forum parties to power operations and international scandals.

Daniel collected materials for several years, some stories appeared on Medusa, and for the retelling of articles by Daniel Andrew Kramer from the New York Times in 2017 received the Pulitzer Prize.

But hacking - like any crime - is too closed a topic. Real stories are only passed on between mouths. And the book leaves the impression of insanely inflating the curiosity of incompleteness - as if about each of its hero you can add a three-volume volume of "how it really was."

With the permission of the publisher, we are publishing a small excerpt about the Lurk group, which plundered Russian banks in 2015-16.

In the summer of 2015, the Russian Central Bank established Fincert, a center for monitoring and responding to computer incidents in the financial and credit sector. Through it, banks exchange information about computer attacks, analyze them and receive recommendations on protection against special services. There are many such attacks: in June 2016, Sberbank estimated the losses of the Russian economy from cybercrime at 600 billion rubles - at the same time the bank had a subsidiary Bizon, which is engaged in the information security of the enterprise.

In the first reportFincert's results (from October 2015 to March 2016) describe 21 targeted attacks on bank infrastructure; As a result of these events, 12 criminal cases were instituted. Most of these attacks were the work of one group, which was named Lurk in honor of the virus of the same name developed by hackers: with its help, money was stolen from commercial enterprises and banks.

Police and cybersecurity experts have been looking for members of the group since 2011. For a long time, the search was unsuccessful - by 2016, the group had stolen about three billion rubles from Russian banks, more than any other hackers.

The Lurk virus was different from what the investigators had seen before. When the program was run in the laboratory for the test, it did nothing (that’s why it was called Lurk — from English “to hide”). Later it turned out that Lurk was designed as a modular system: the program gradually loads additional blocks with various functionalities - from intercepting characters, logins and passwords entered on the keyboard to the ability to record a video stream from the screen of an infected computer.

To spread the virus, the group hacked sites visited by bank employees: from online media (for example, RIA Novosti and Gazeta.ru) to accounting forums. Hackers exploited a vulnerability in an ad banner exchange system and distributed malware through them. At some sites, hackers made a link to the virus for a short while: on the forum of one of the magazines for accountants, it appeared on weekdays at lunchtime for two hours, but during this time Lurk found several suitable victims.

By clicking on the banner, the user was taken to the exploit page, after which the information collection began on the attacked computer - mainly hackers were interested in the remote banking service program. Details in bank payment orders were replaced with the necessary ones, and unauthorized transfers were sent to the accounts of companies associated with the grouping. According to Sergei Golovanov of Kaspersky Lab, in such cases, groups usually use one-day companies, “which do not care what to transfer and cash out”: the money received is cashed there, put into bags and bookmarks are left in city parks where hackers pick them up . Members of the group carefully concealed their actions: encrypted all daily correspondence, registered domains for fake users. “Attackers use a triple VPN, Thor, secret chats, but the problem is that even a well-functioning mechanism fails,” explains Golovanov. - That VPN will fall off, then the secret chat is not so secret, then one instead of calling via Telegram, just called from the phone. This is a human factor. And when you have been collecting a database for years, you need to look for such accidents. After that, law enforcement officers can contact the providers to find out who went to such an IP address and at what time. And then the case is built. " And when you have been collecting a database for years, you need to look for such accidents. After that, law enforcement officers can contact the providers to find out who went to such an IP address and at what time. And then the case is built. " And when you have been collecting a database for years, you need to look for such accidents. After that, law enforcement officers can contact the providers to find out who went to such an IP address and at what time. And then the case is built. "

The detention of Lurk hackers looked like an action movie. EMERCOM officers cut down locks in hacker country houses and apartments in different parts of Yekaterinburg, after which FSB officers screamed inside, grabbed hackers and threw them to the floor, searched the premises. After that, the suspects were put on a bus, brought to the airport, taken along the runway and taken to a cargo plane, which flew to Moscow.

In the garages owned by hackers, they found cars - expensive models of Audi, Cadillacs, and Mercedes. Also found a watch inlaid with 272 diamonds. They seized jewelry worth 12 million rubles and weapons. In total, the police conducted about 80 searches in 15 regions and detained about 50 people.

In particular, all the technical experts of the group were arrested. Ruslan Stoyanov, an employee of Kaspersky Lab, who was involved in the investigation of Lurk crimes along with special services, said that many of them were looking for management on regular sites for selecting personnel for remote work. The fact that the work would be illegal was not mentioned in the announcements, and Lurk offered a salary higher than the market salary, and it was possible to work from home.

“Every morning, except weekends, in different parts of Russia and Ukraine, individuals went to computers and started working,” Stoyanov described. “The programmers twisted the functions of the next version of the [virus], the testers checked it, then the person responsible for the botnet uploaded everything to the command server, after which there was an automatic update on the bot computers.”

The consideration of the case of the group in court began in the fall of 2017 and continued at the beginning of 2019 - due to the volume of the case, in which about six hundred volumes. A hacker lawyer who was hiding his name stated that none of the suspects would make a deal with the investigation, but some admitted part of the charges. “Our clients did work on developing various parts of the Lurk virus, but many simply were not aware that this was a Trojan,” he explained. “Someone made part of the algorithms that could successfully work in search engines.”

The case of one of the hackers of the group was brought into a separate production, and he got 5 years, including for breaking the airport network of Yekaterinburg.

In recent decades, in Russia, special services have managed to defeat most of the large hacker groups that violated the main rule - "Do not work for ru": Carberp (stole about one and a half billion rubles from the accounts of Russian banks), Anunak (stole more than a billion rubles from the accounts of Russian banks), Paunch (created platforms for attacks through which up to half of infections across the world passed) and so on. The incomes of such groups are comparable to the earnings of arms dealers, and dozens of people are in it besides the hackers themselves - security guards, drivers, cash-in workers, owners of sites on which new exploits appear, and so on.