In 1983, this computer from Bella Labs became the first grandmaster.

- Transfer

Belle used brute force to beat other computers and people

Checkmate: Belle was the first chess computer developed at Bell's laboratories in the early 1970s.

Author of the article, Allison Marsh is an associate professor of history at the University of South Carolina and one of the directors of the Johnson Institute of Science, Technology and Society at this university.

Chess is a difficult game. This is a strategic game of two opponents without hidden information, in which all potential moves of the enemy are known from the very beginning. With each move, players communicate their intentions and try to predict possible return moves. The ability to represent a game several moves ahead is a recipe for victory, which mathematicians and logicians have long been interested in.

Despite the early mechanical machines that played chess — and at least one rally — mechanical gaming remained a hypothetical issue until the advent of digital computers. While working on his doctoral dissertation in the early 1940s, German computer engineering pioneer Konrad Zuse used computer chess as an example when developing a high-level programming language called the plancalcule . But because of World War II, his work was not published until 1972. Since Zuse's work remained unknown to British and American engineers, Norbert Wiener , Alan Turing and especially Claude Shannon (with his 1950 work "Programming a computer for playing chess ") paved the way for thinking about computer chess.

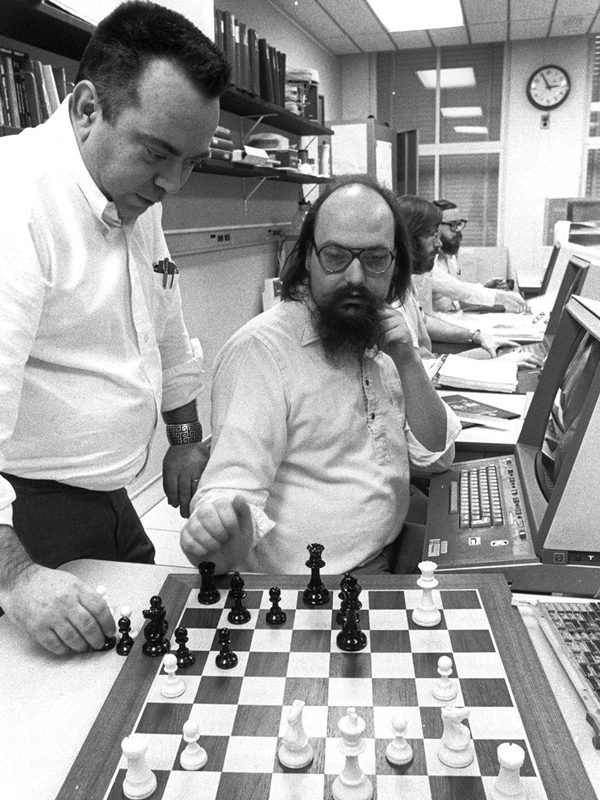

Starting work in the early 1970s, researchers from telephone laboratories Bella Ken Thompson and Joe Condon developed Belle, a computer that played chess. Thompson was one of the creators of the operating room Unix systems, but still he was very fond of chess. he grew up in the era of Bobby Fischer , and youth participated in chess tournaments. in the laboratory, he joined Bell in 1966, received a master's degree in electrical engineering and computer science at the California univ rsitete Berkeley.

Joe Condon was a physicist by training, worked in the metallurgical department of Bell Laboratories. His research has helped reveal the electronic band structuremetals, and interests developed with the advent of digital computers. Thompson met Condon when he and his Unix development partner, Dennis Ritchie , began work on the Space Travel game using the PDP-7 microcomputer, which was Condon's responsibility. Thompson and Condon subsequently worked together on a variety of projects, including promoting C as the primary language for use in the AT&T switch system.

The Belle project began as a software project - Thompson wrote a trial chess program in an early instruction for Unix. After Condon joined the team, the program turned into a hybrid chess computer, in which Thompson was responsible for programming, and Condon developed the hardware.

Ken Thompson (sitting) was responsible for programming, and Condon designed the hardware.

Belle had three main parts: a move generator, a position evaluator, and a permutation table. The move generator determined the most valuable of the threatened pieces and the least valuable attacking piece, and sorted the potential moves based on this information. The position evaluator noted the location of the king and his relative safety at different stages of the game. The permutation table contained a memory cache with potential moves, which made the evaluation more efficient.

Belle used brute force. He went over all the possible moves that the player can make in the current position, and considered all the moves that the opponent could make. Initially, Belle could count the game four moves ahead. When Belle debuted onThe North American Computer Chess Championship under the auspices of the Computer Science Association in 1978, where he won first place, he knew how to calculate the game eight moves ahead. After that, Belle won the championship four more times. In 1983, he also became the first computer to win the title of Grandmaster.

Computer chess programmers often came up against them when trying to put their program against people - some of them suspected the program of cheating, while others were simply afraid. Wanting to try out Belle at a local chess club, Thompson put a lot of effort into establishing personal connections. He offered his opponents a printout of a computer analysis of the match. If Bell won in mixed tournaments, where computers played with people, he refused to take the prize, offering it to the next person in order. As a result, Belle played weekly at Westfield Chess Club in Westfield (New Jersey) for almost ten years.

In contrast to human chess competitions, where they were silent so as not to distract the players, computer chess tournaments were a rather noisy place where people discussed and argued about various algorithms and game strategies. In 2005, Thompson remembered them with pleasure. After the tournament, he felt a surge of strength, and returned to the laboratory to fight the next task.

For a computer, Belle had a vibrant life - once he even became the center of a corporate rally. In 1978, Bell's lab computer scientist Mike Lesk , another member of the Unix team, borrowed AT&T letterhead from John Dibats, chairman of the board, and wrote a fake memowhere announced the termination of the project T. Belle Computer.

The center of the comic note was the philosophical question: is the game of man and computer a form of communication or data processing? The note stated that the second option was correct, which is why Belle violated the 1956 antimonopoly order, which prohibited the company from doing business with computers. In fact, AT&T directors never forced Belle's creators to stop playing or invent games at work, probably because their distractions led to cost-effective research. The raffle gained fame after Dennis Ritchie wrote about it in an article in 2001for a special issue of the magazine of the international computer games association dedicated to Thompson's contribution to computer chess.

In his memoirs, Thompson describes how Belle also became the object of international intrigue. In early 1980, a Soviet electrical engineer, computer scientist and grandmaster Mikhail Moiseyevich Botvinnik suggested that Thompson bring Belle to Moscow for demonstrations. He flew out of New York Airport to them. John F. Kennedy, and suddenly discovered that Belle was not on his plane.

Thompson learned the fate of Belle after spending several days in Moscow. Bella's laboratory security officer, who worked part-time at the airport, saw a lab box labeled “computer,” which was taken through customs. The guard warned his friends from the laboratories, this story reached Condon, and he called Thompson.

Condon warned Thompson to discard spare parts for Belle that he had brought with him. “You are likely to be arrested upon returning home,” he said. "For what?" Asked Thompson. “For smuggling computers into Russia,” Condon replied.

In his memoirs, Thompson suggests that Belle fell victim to the Reagan administration’s opinion about the “technology leak” in the USSR. Overly zealous US customs officers noticed Thompson's box and confiscated it, but did not inform either him or the lab. His Moscow host agreed that Reagan should be blamed. When Thompson met with them to explain that Belle had been detained at customs, the head of the Soviet chess club noticed that Ayatollah Khomeini had legally banned chess in Iran on the grounds that they were nasty to God. “Don't you think Reagan did this to ban chess in the US?” He asked Thompson.

On his return to the states, Thompson took Condon's advice and left spare parts in Germany. On arrival, no one arrested him, neither for smuggling, nor for anything else. However, when he tried to pick up Belle at the airport, he was refused on the grounds that he was violating the export law - the obsolete Hewlett-Packard Belle monitor was on the list of items prohibited for export. Bell's labs paid a fine, and Belle was eventually returned.

After Belle dominated the world of computer chess for several years, her star began to roll as more powerful computers with trickier algorithms appeared. Chief among them was IBM's Deep Blue, which attracted international attention in 1996 by winning the game against world champion Garry Kasparov. As a result, Kasparov won the match, but this laid the foundation for a rematch. The following year, having undergone a significant update, Deep Blue defeated Kasparov, becoming the first computer to beat the world champion among people in a tournament where time is regulated.

My attention was drawn to Belle by photographer Peter Adams, and his story shows how important it is to be friends with archivists. Adams photographed Thompson and many of his Bell lab colleagues for the Open Source Faces series. In Adams' research process, Bell Lab corporate archivist Ed Ed Eckert gave him permission to photograph some artifacts associated with the Unix research lab. Adams wrote Belle on his wish list, but suggested that he is now in some museum collection. To his amazement, he found out that the car was still standing at Nokia Bell Labs in Murray Hill (New Jersey). As Adams wrote to me, “until now you could see on it the wear and tear from all the chess games he played.”