Antiquities: Philips DCC, Loser Cassette

Digital cassette Philips Digital Compact Cassette went on sale in late 1992, just a few weeks ahead of its main competitor - Sony Minidisc. In 1996, the development of the format was stopped: the remnants of the equipment were sold out, cassettes were produced and sold for several more years. The DCC format lost in the fight both with the competitor and over time: the consumer could not be convinced of the advantages of home digital recording.

This article is a logical continuation of my two ( 1 , 2 ) mini-disc materials. Sony, too, could stop promoting its rewritable digital audio format due to low sales, but decided to continue. Therefore, the minidisk turned out to be a more developed format, more accessible for collectors, and for many it causes a certain nostalgia. DCC has almost none of this. Nevertheless, a lot of effort was put into the development of the format, and artifacts of those times are enough to study.

I recently bought a Philips DCC900 tape recorder, the first commercially available 1992 model. Today I’ll tell you about impressions, about other available versions of devices (and there were surprisingly many of them), and I will touch on a topic that dramatically complicated Philips’s life. The fact is that, unlike the minidisk, DCC had backward compatibility: on all devices you can play regular audio tapes. The difficulties associated with supporting such a harsh legacy, it seems to me, have exceeded the benefits of compatibility.

I keep a diary of a collector of old pieces of iron in real time in a Telegram .

About the DCC format, less information is available than about the minidisk. Unfortunately, there is no evidence from the developers - it would be interesting to know how and why they made certain decisions. There is a lot of information on device repair on the DCC Museum Channel : but there you will find more likely instructions for repairing models available for sale. In June, the creators of the museum are planning the premiere of a documentary about a digital cassette.

Why did Philips go all the way to storing digital audio on tape? The obvious answer: the same Dutch company created a compact cassette in the sixties. One source mentions negotiations between Sony and Philips on working together on a digital rewritable medium, but for some reason, the two companies did not continue collaborating on the development of the CD in the early eighties. My guess: the cassette was chosen as the cheapest medium, the production technology of which has already been worked out.

On the left is a digital cassette with a shielded security shutter, in the normal position completely covering the tape. On the right is a regular cassette.

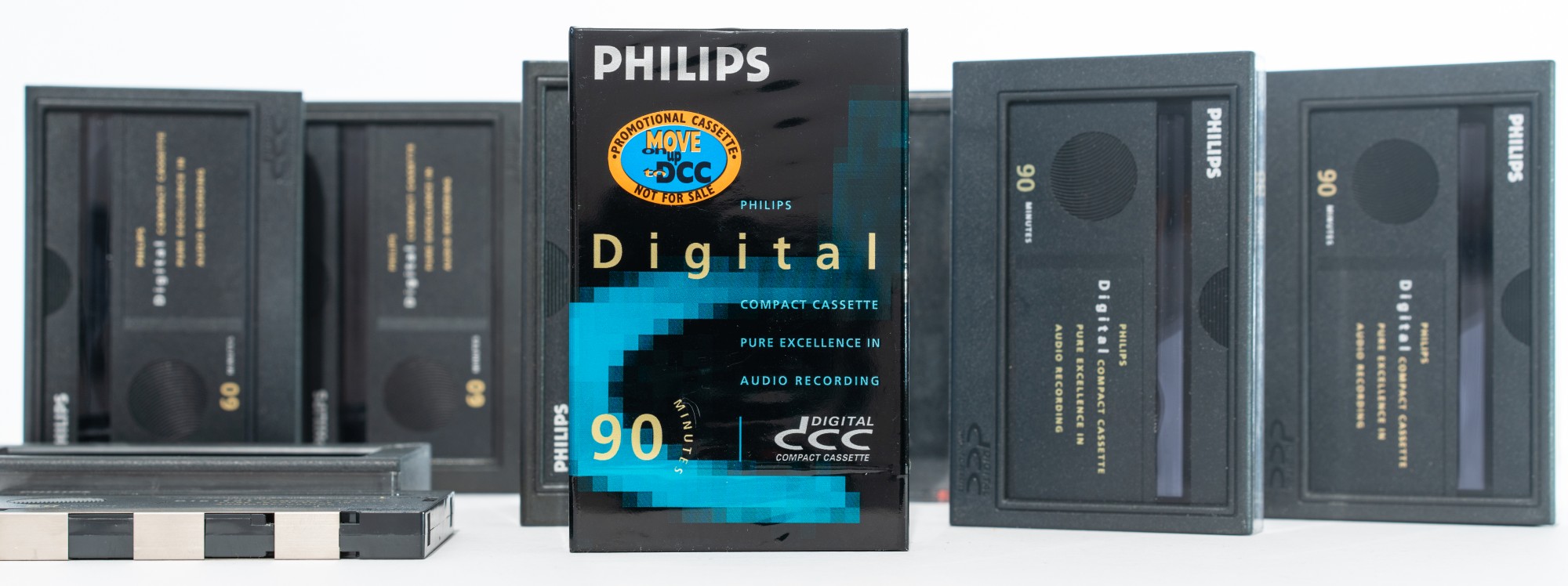

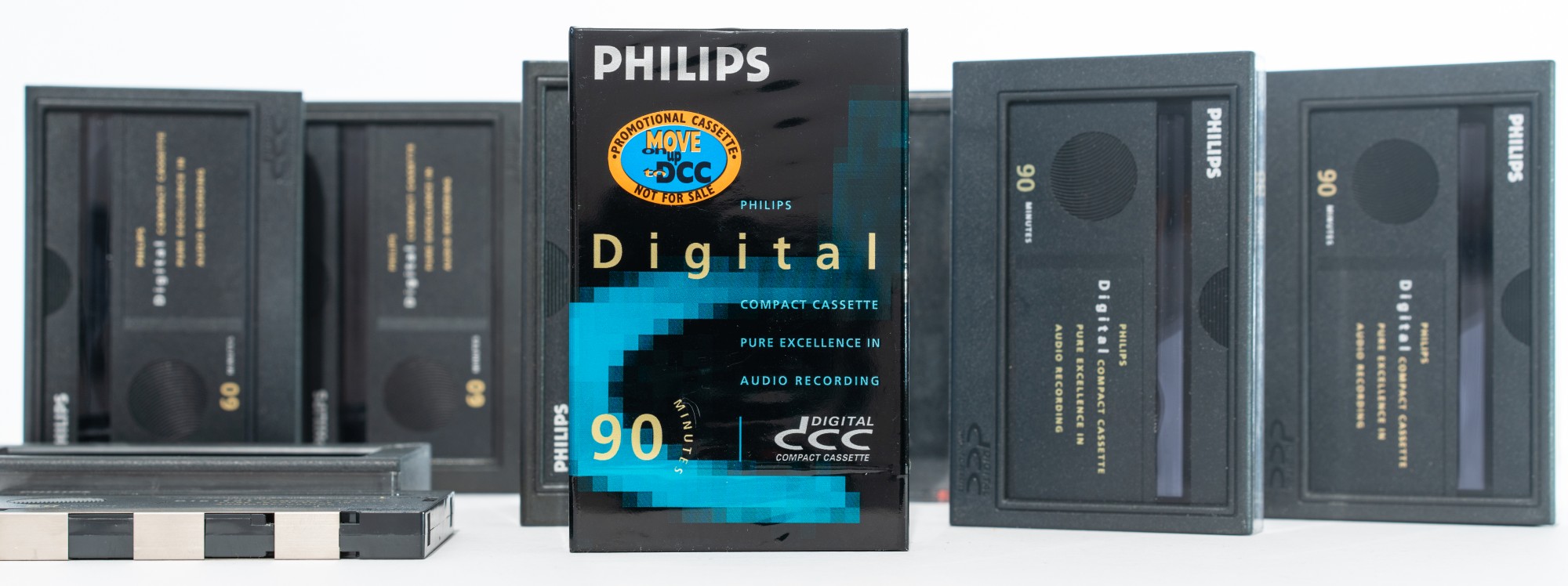

Then I forgot to rewind a regular cartridge, you have to take a word: the chemical composition of magnetic tape is different from that of a conventional cartridge. The tape in DCC media is either very similar in composition or identical to tape in video cassettes. At DCC, metal guides are still noticeable where the magnetic head contacts the tape: together with the counterpart in the tape recorder, they fix the tape relative to the head. The tape winding holes are located only on one side of the cassette: auto-reverse is a mandatory feature, and you do not need to turn the cassette over.

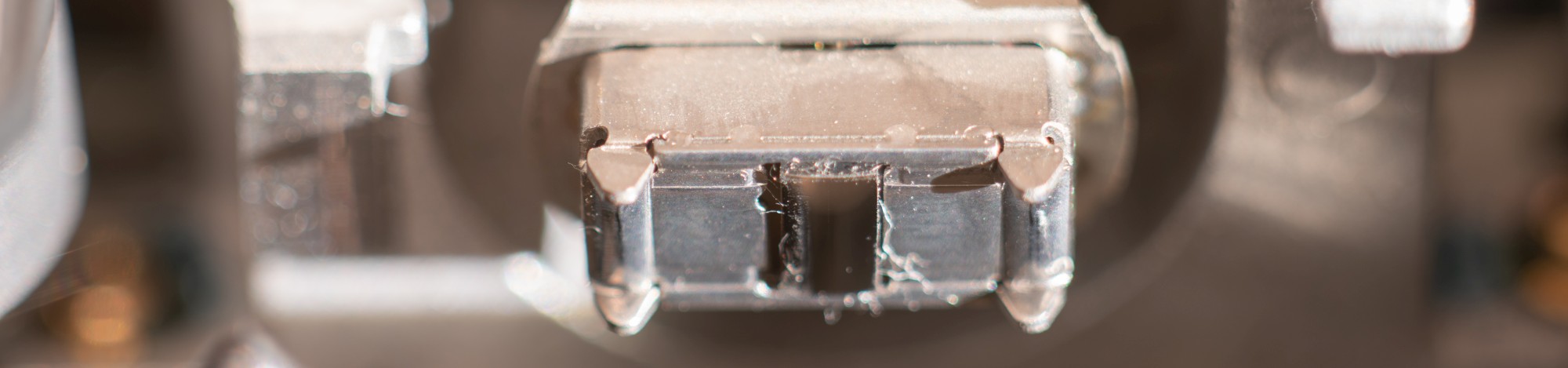

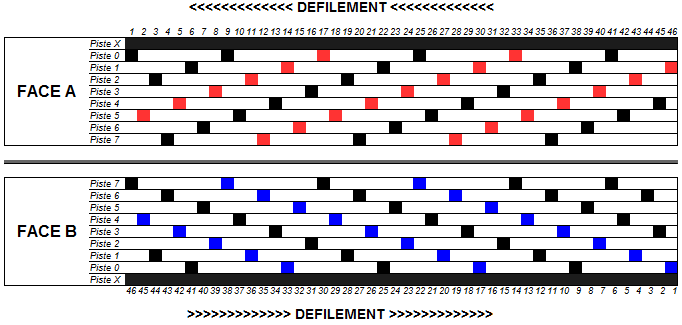

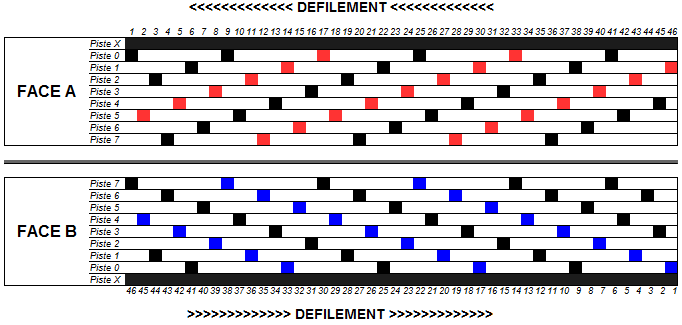

Then the difficulties begin. Both the DCC format and the cassette were preceded by the Digital Audio Tape format, which uses a rotating head for reading and writing, as in VCRs. This design allowed us to record more data on the same area of the tape, but it was more difficult and more expensive to implement (and certainly not compatible with old cassettes). In DCC, data is written to the cassette in several parallel tracks: there are eight in total on each side, plus an additional ninth track for related data - time markers, identifiers for starting a new track and text information.

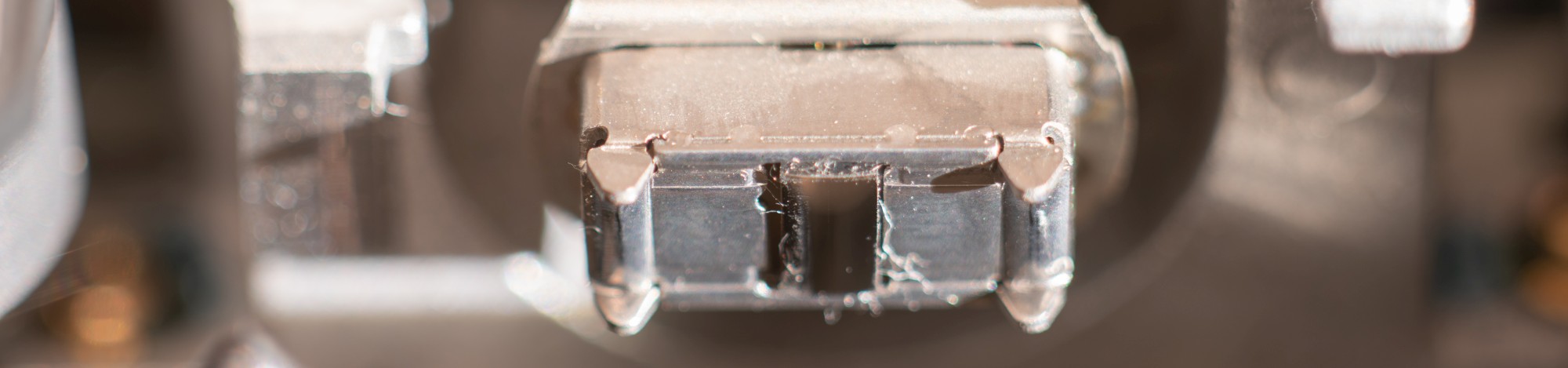

As a result, a magnetic head for reading and writing is almost the most innovative element of Philips DCC technology. In my Philips DCC900, the magnetic head is actually a 20-head sandwich: 9 for reading, 9 for writing, and two more for reading traditional CDs. In the latest portable devices, the head did not rotate, reading and writing on both sides of the tape was provided by a double set of heads - only forty pieces.

DCC data is staggered at a bit rate of 768 kilobits per second. Taking into account the data for error correction (it is provided both by a tricky distribution of data on tracks and by Eight-To-Fourteen conversion , as in CDs), the real bitrate is 384 kilobits per second or 260 megabytes for a 90-minute cassette. This is slightly larger than the minidisk (there were 292 kilobits in the original version of the format). To store audio, respectively, lossy compression is required. Philips used the minimally modified standard Mpeg-1 Layer 2, which was also used on Video CDs. There is a curious articlein Stereophile magazine for April 1991. The correspondent who visited the Philips prototype was not able to distinguish between the sound of the “compressed” sound of a digital cassette and the original on a CD. Given that Stereophile has always been and remains a magazine for audiophiles, this is serious praise. The first-generation Sony Minidisc compression artifacts were audible even to those who did not have golden ears, and in this sense, Philips gained an advantage.

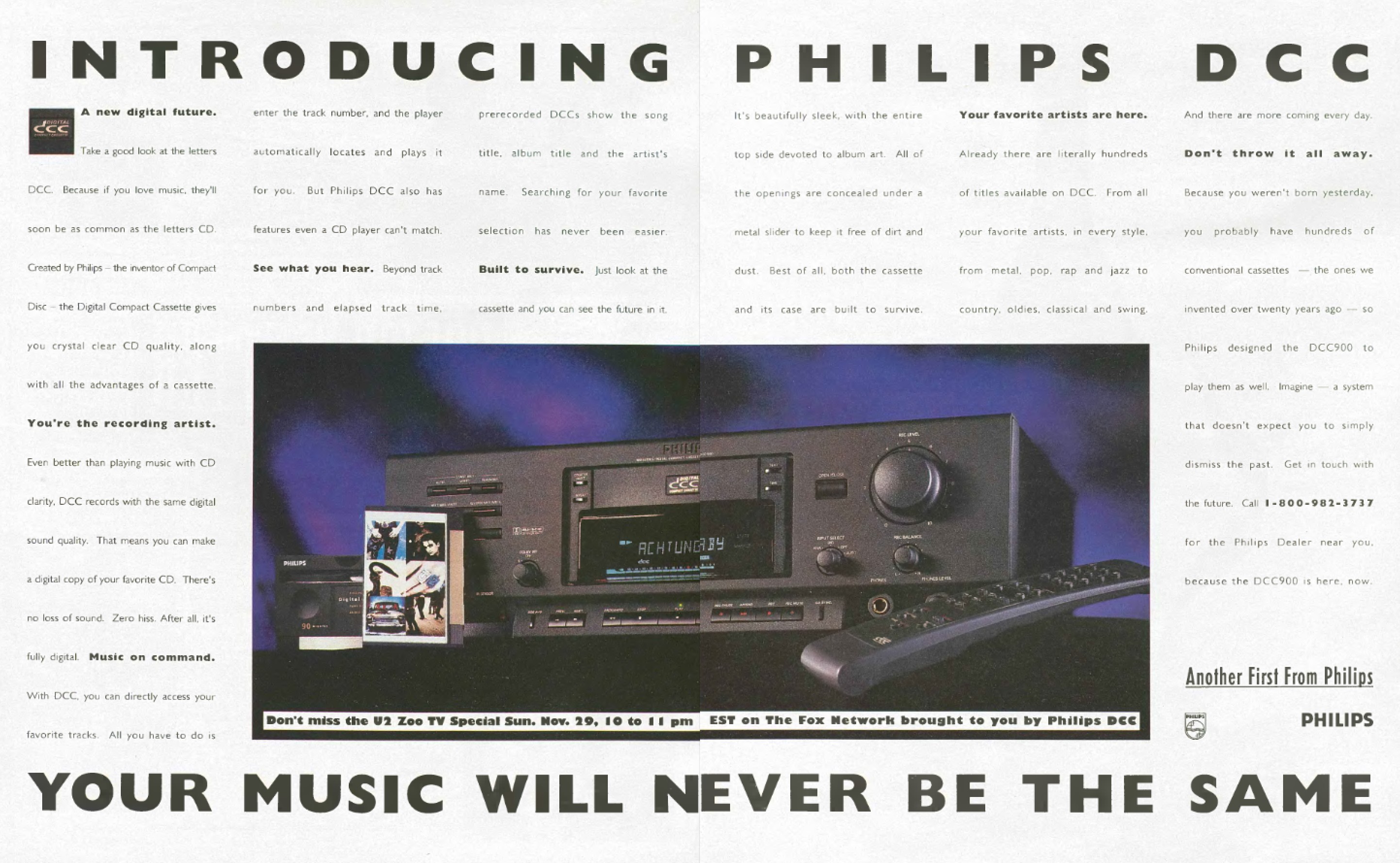

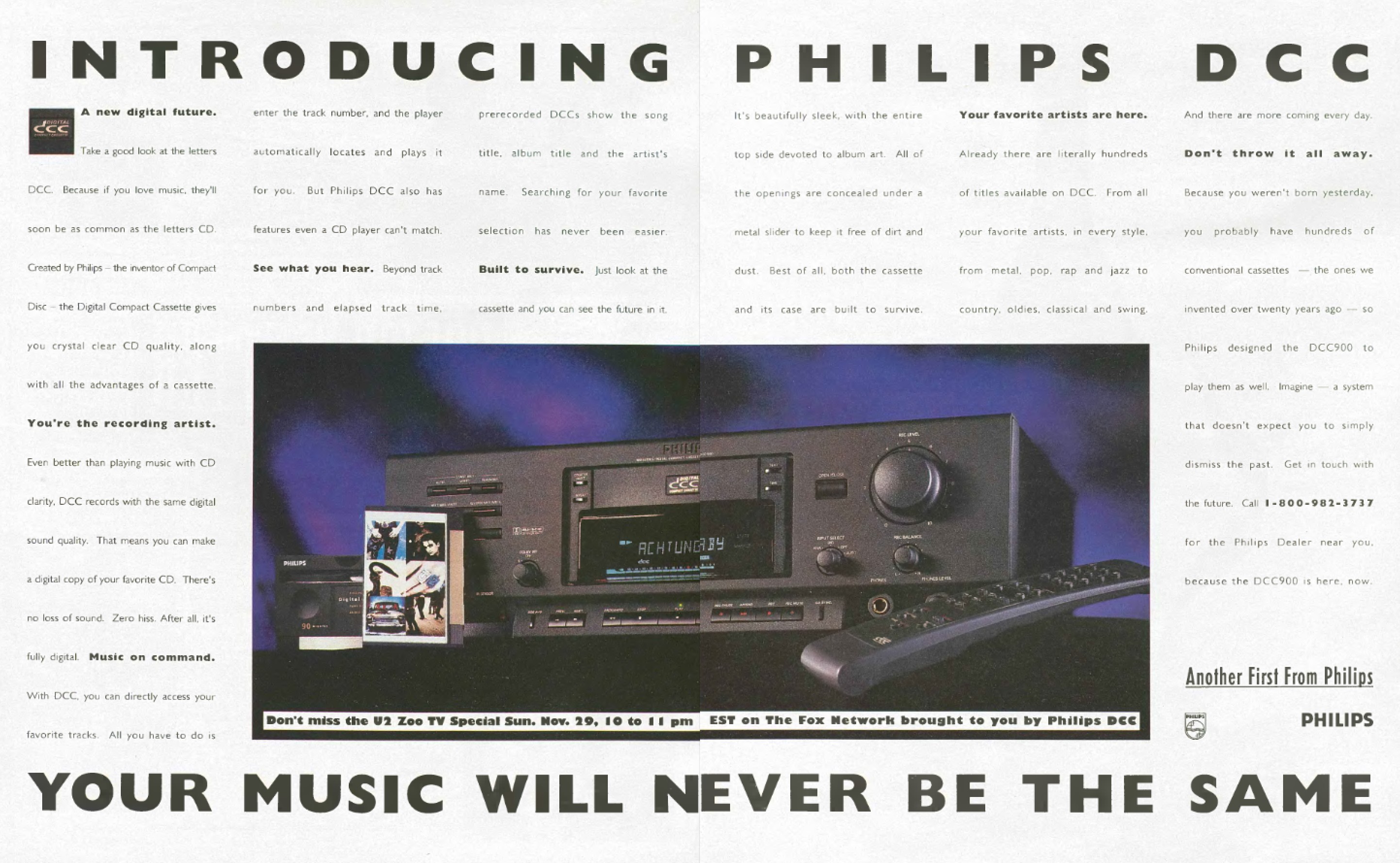

Philips did a lot to promote the format, and it did better than its competitor. Contracts were signed with independent music studios, at the time of the start of sales an extensive catalog of recording tapes was immediately available. In music and simply popular publications in the USA of those years, I found DCC ads (as in the picture above) more often than minidisc ads. Everything seemed to go according to plan. Why didn’t it work out? To answer this question, I needed to purchase a live device and test the format on myself.

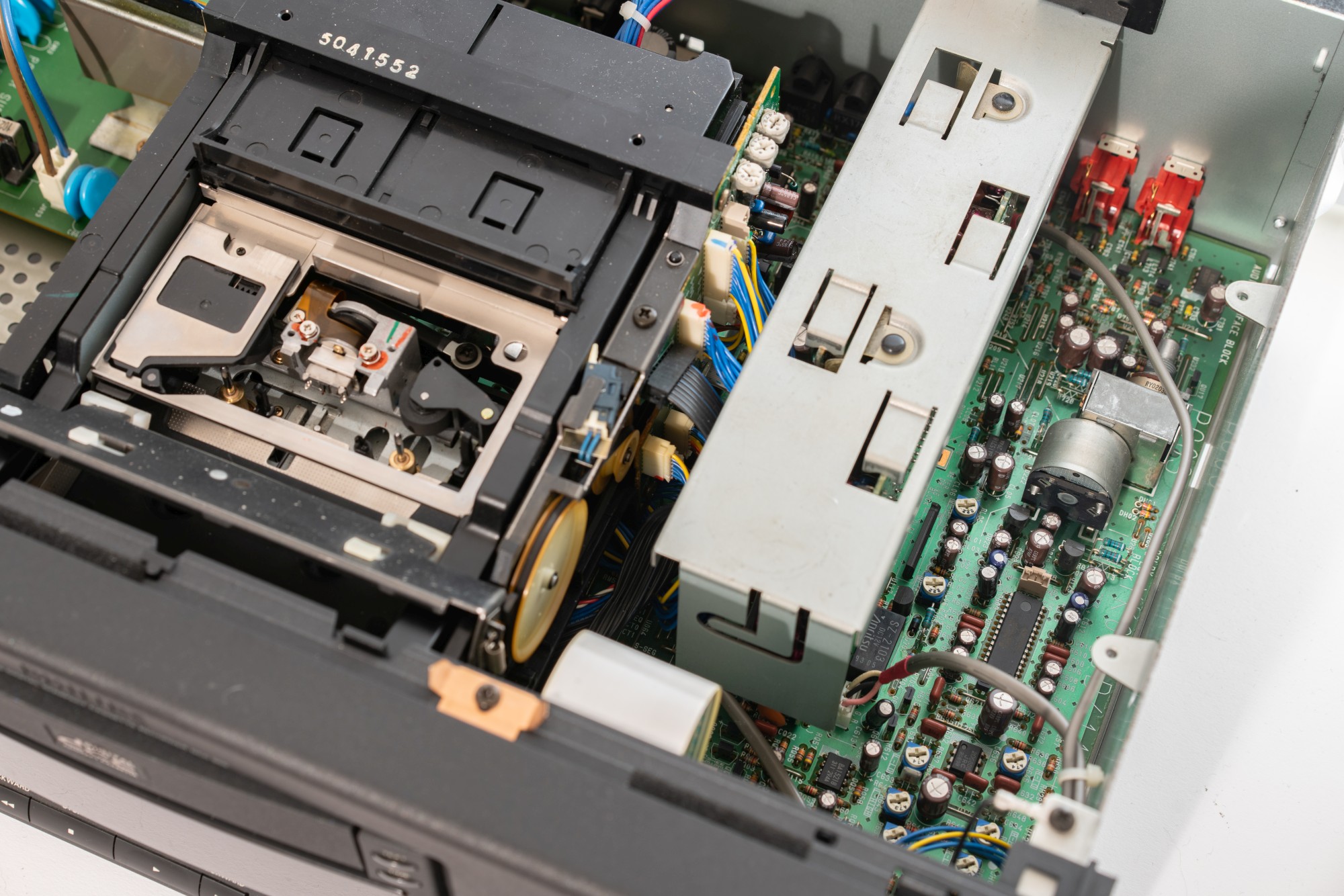

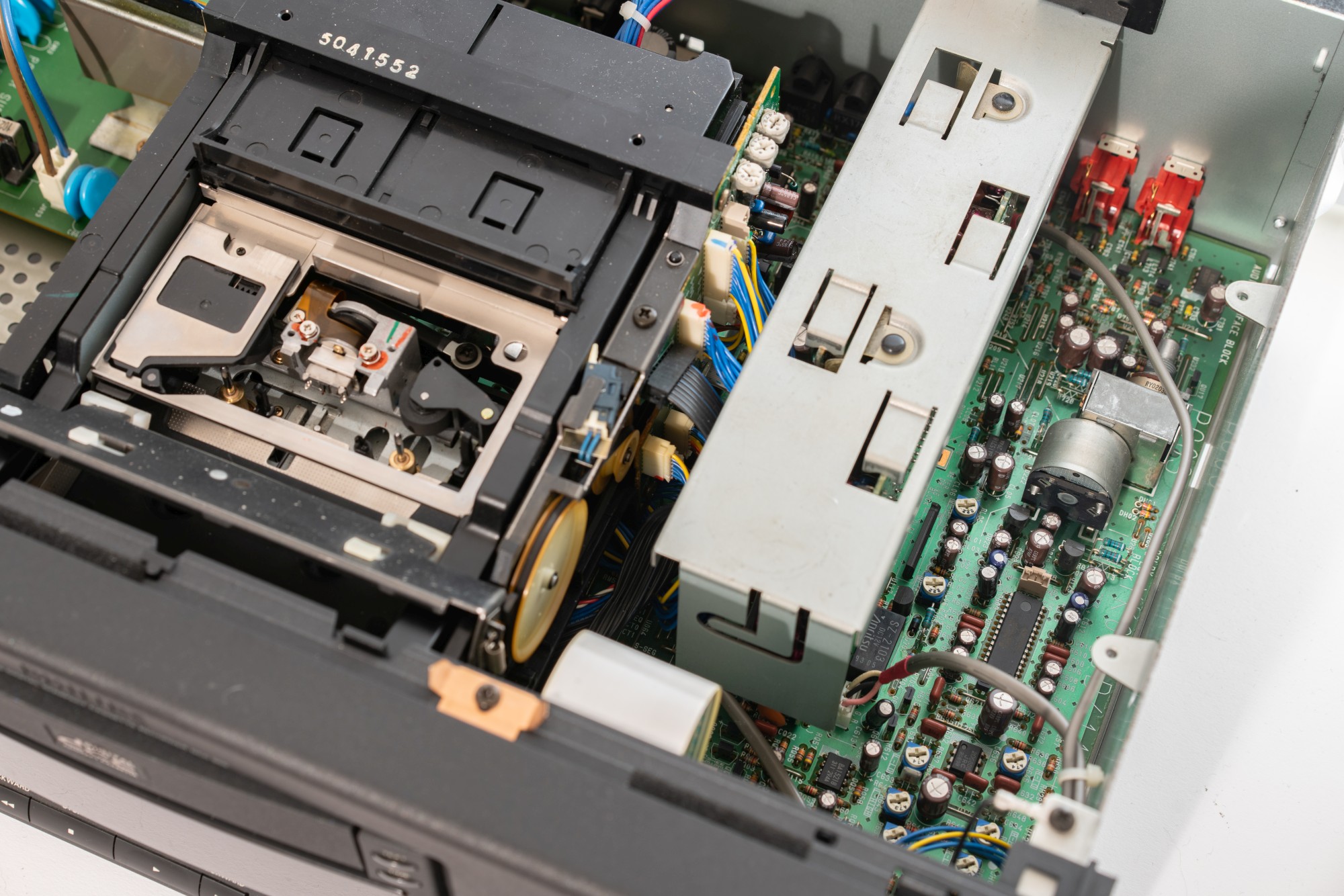

Philips DCC900 was released in 1992, and what a hell, he is huge. Unlike Sony, which immediately bet on portable, portable players for digital cassettes appeared only in the next, 1993. For comparison, I placed a Kenwood minidisk deck on top, but it was made rather large for beauty: inside it is quite empty. But Philips is not so.

On the main board below is located mainly the analog part. The digital one is hidden under a metal screen, and two more boards are mounted on a cassette mechanism.

Prototypes of Philips DCC tape recorders have been designed for vertical cassette installation. Almost all real devices have a slot drive, almost like a CD. The ninetieth series of Philips devices in the nineties was the most top-end: you could assemble a set of a CD player, tuner, amplifier, DCC recorder, and all of them could be controlled via a common bus. The price of a digital tape recorder came out rather big - $ 800 in the United States. Cassettes sold for $ 8-10, slightly cheaper than mini-discs at the dawn of the format. At some point, the expected savings on cheap media disappeared somewhere. But on digital tapes it was immediately possible to record 90 minutes of music, while the first minidiscs were 60 minutes.

Okay, let's try to record something. Like minidisc devices, the DCC900 can record from analog and digital inputs. First-generation devices could process 16-bit digital sound, in later models the dynamic range was expanded to 18 bits - however, the minidisk also learned how to do this in 1996. The tape recorder writes the so-called lead-in on an empty cassette - essentially a marker indicating that the data starts here. From this point, during further recording on the very ninth track with data, an absolute timer begins to be recorded. If there was already a recording on the tape, the tape recorder searches for an existing marker and plays a piece of the old one before starting a new recording - what if there is something valuable there? Then everything is simple: we write a sound, if necessary we stop it. The tape recorder always rewinds the tape so that the next track starts exactly there, where the previous one ended. If necessary, press the button on the remote control or on the device itself to indicate a new track.

Difficulties begin when you reach the end of the tape. Here, the developers have provided two options. Where you find that enough content for the first side, you can put one of two markers. In one case, seeing the desired marker, the tape recorder stops playback (or recording), winds the tape to the end, and starts a new track on side B. In another, the tape recorder instantly switches to the second side. This option leads to the loss of several meters of tape both on the one hand and on the other, but switching between tracks on different sides is as quick as possible (but there is still a delay). Compare this with a minidisk - there is basically no such problem.

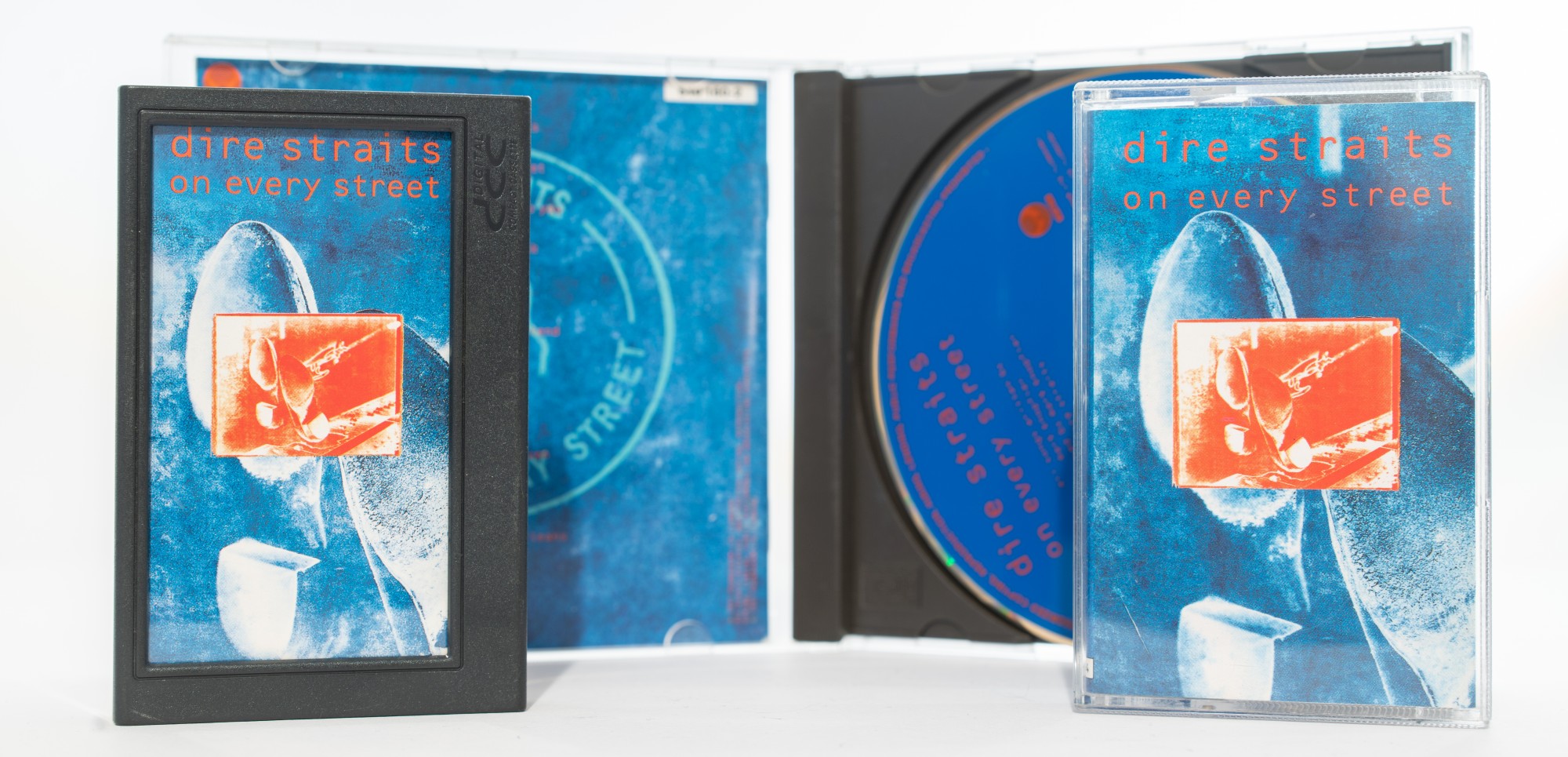

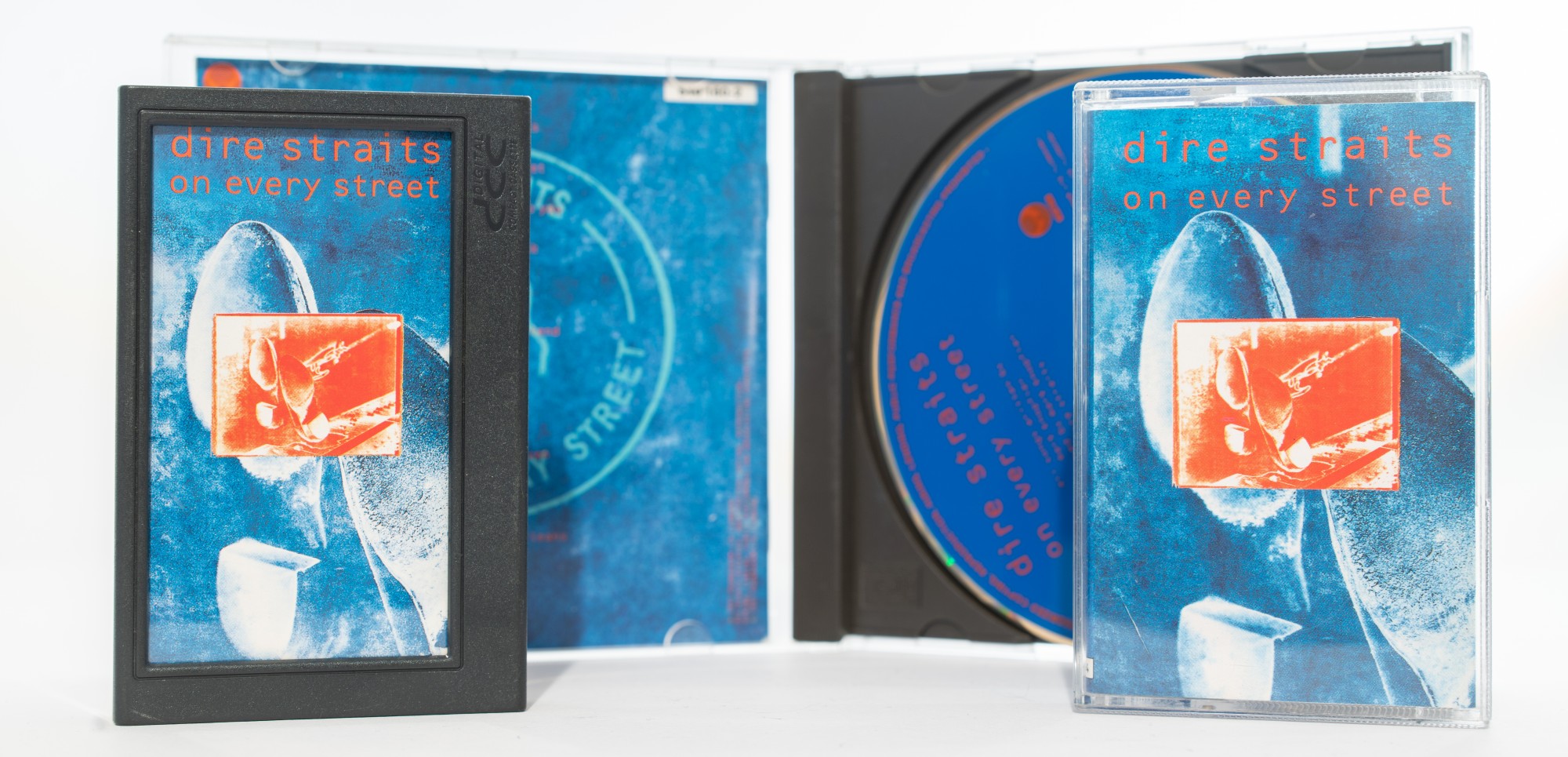

I have long wanted to buy the same album on different media. Albums on DCC are now rare: the tape on the left cost me 10 times more than the tape on the right, or CD .

First-generation tape recorders did not know how to write track names, artist names, and album names onto a cassette. In general, if you insert a self-recording cassette into the DCC900, it only shows the absolute time during playback. The track number will be displayed when you reach the nearest marker. Therefore, cassettes with music from the store are the only way to appreciate the format in all its beauty: here is text information (there was even a plan to record the lyrics of the songs), and, most importantly, data on all tracks are continuously recorded on the data track. At any time, you can select any track on the album, and the tape recorder will rewind the tape and, if necessary, switch between the parties. Again, the advantage of the minidisk is obvious: it has a table of contents where you can write all the information,

All this cassette laziness was normal in the analog era, but compared to CD, the DCC standard was seriously losing. Want to switch to a new track? Wait. Want to erase an existing marker? First find it, then wash it. If 10 tracks were recorded on the cassette, and then the part was re-recorded again, you had to activate a separate feature that scrolled the entire tape in search of markers and changed the track numbers, if necessary.

Some of the shortcomings of the first generation tape recorders were fixed in devices released later. In the second generation, the cassette mechanism was completely redone: the carrier was now inserted sideways. They released portable players: they weighed a pound, worked on a proprietary battery and did not know how to record. In the third-generation devices, the jambs were fixed. The last Philips DCC951 stationary tape recorder was able to rewind the tape from beginning to end in a minute, supported 18-bit sound, and let you enter the names of tracks and albums.

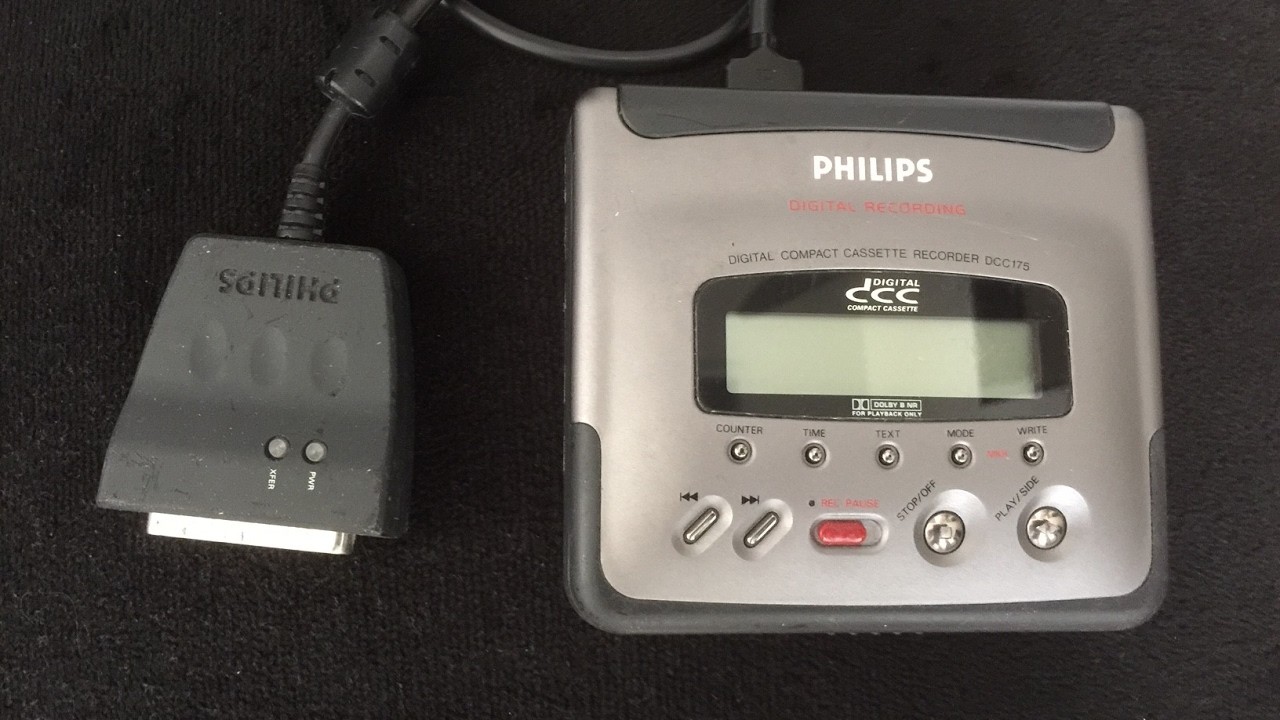

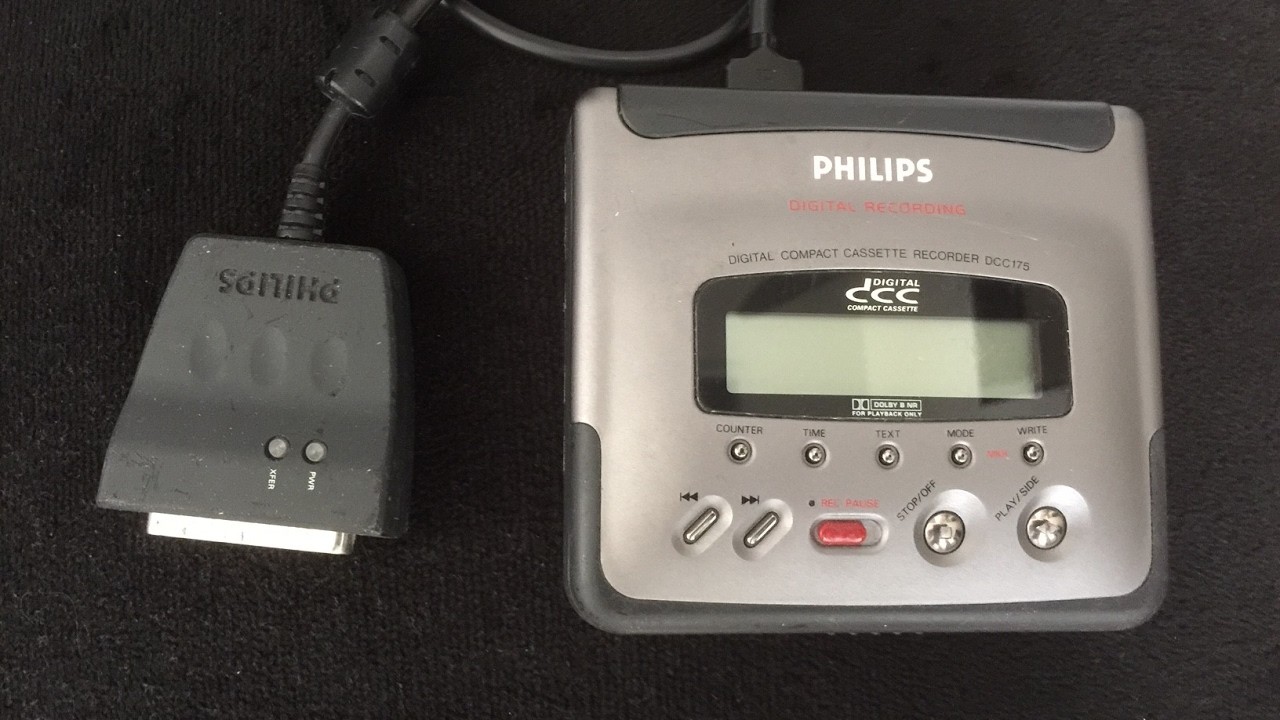

Philips DCC170 and 175 portable players were relatively compact and supported recording, including from digital sources. The most interesting portable model is the Philips DCC175. Using an optional cable, it could be connected via a parallel port to a computer. The software supported Windows 3.1 and Windows 95. It was possible to write data (250 megabytes to a 90-minute medium) and music onto a cassette, along with track names and navigation. Unlike Sony, Philips was not worried about protecting the data compression format - it was already half-open anyway. Modern releases on DCC cassettes (a couple of albums released last year) are written on a modified version of DCC175.

Unfortunately, this is the most difficult to collect artifact. Portable players, designed and manufactured not by Philips, but by the Japanese partner Matsushita, generally sold a little. A DCC175 was sold only in the Netherlands, and the optional interface cable to it was generally released in a circulation of 1000 pieces.

In 2019, I acquired a digital tape recorder, planning to experiment with the format, and to listen to ordinary audio tapes. And what? A convenient device with a remote control and auto reverse, the most for playback, and you can record on another technique. Alas, I failed to investigate this use case normally - the whole thing is in leaking capacitors. For those two boards, mounted on the DCC900 mechanism itself, SMD capacitors were used for compactness, which in all tape recorders of this series follow over time. I bought a tape recorder as a “serviced” one, but alas, the previous owner replaced the capacitors only on the board responsible for the digital signal. The analog channel simply does not work normally - the sound of one channel is missing, in the second it is very distorted. Have to solder. In general, the test of time minidisc survived better than DCC. This stems from the bet on the cassette: in each device, it is necessary to replace the drive belts, and in my case also change the capacitors. Finding a mini-CD deck in working order is much easier, and the mini-discs themselves are generally unkillable. In the early DCC cassettes, the unsuccessful material of the pad used to press the tape to the head was used, they not only creak terribly, but they also do not read plainly - the tape moves in jerks.

Why did the format fail? Previously, competition with Sony was considered the main reason. In the home digital audio market, there was a typical format war, a battle similar to VHS vs. Betamax or Blu-ray vs. HD DVD. In fact, almost all storage media have gone through this stage, including even a compact cassette, but excluding a CD. One of the two formats was doomed to failure, but now we know that absolutely all physical data carriers were doomed. Both minidisk and DCC lost to cheap CD-R discs and file-sharing networks. Philips did the right thing, fixing the losses, while Sony decided to continue investing in a hopeless format, which, admittedly, was still more convenient than a digital cassette.

There are two things that interest me in DCC history. First, was it possible to avoid such a failure and not invest in the development of a digital cassette at all? It is unlikely that such complex projects lasted for many years, and they began in the mid-late eighties, when there were far from penny blanks, computers were low-powered, and the web did not exist at all. At the same time, there is an increase in sales of CDs, and in general, everything is digital, and analog is considered obsolete. It is curious that since then the situation has turned 180 degrees. If you behave carefully, you can finally give up the initiative to competitors and go bankrupt. If you want, you don’t want, but you have to take risks.

Secondly, my introduction to DCC shows that legacy support sometimes brings more problems than solutions. I’m already fantasizing here, but in theory, what prevented writing data on a tape in only one direction? Thus, simplifying the mechanism: you do not need auto-reverse, you do not need to invent complex ways to switch from one side to the other, there is no inevitable pause between tracks. But then the backward compatibility that marketers had relied on would be lost. I myself prefer formats or services that remain compatible with legacy devices for as long as possible. But the example of a mini-disk shows that sometimes it is worth abandoning a difficult heritage and making it really more convenient and compact.

Наконец, DCC показывает, что продукт может быть неудачным и рано сойти со сцены, но технологии, лежащие в его основе, останутся жить. Технология создания магниторезистивных головок для цифровой кассеты была позаимствована из жестких дисков, и скорее всего новые наработки нашли применение в дальнейшем. На википедии упоминается анекдотический пример применения технологии создания головок для магнитофонов DCC в фильтрах для пива. И DCC, и минидиск внесли свой вклад в развитие сжатия звука с потерями на раннем этапе, и теперь мы косвенно используем эти наработки и при послушивании музыки, и при беспроводной передаче на наушники и через сеть.

In my case, DCC was the first format that I acquired purely for study: there could be no nostalgic background here. I decided on this experiment only because of compatibility with a traditional audio cassette. If I manage to change the capacitors, and if the board was not killed by leaking acid, I will have a backup tape recorder. Fans of a digital cassette (such also exist) strongly recommend that these devices not be used in this way - old cassettes much more quickly get their heads and pressure rollers dirty. But I probably won’t listen to their advice. In the end, we only live once.

This article is a logical continuation of my two ( 1 , 2 ) mini-disc materials. Sony, too, could stop promoting its rewritable digital audio format due to low sales, but decided to continue. Therefore, the minidisk turned out to be a more developed format, more accessible for collectors, and for many it causes a certain nostalgia. DCC has almost none of this. Nevertheless, a lot of effort was put into the development of the format, and artifacts of those times are enough to study.

I recently bought a Philips DCC900 tape recorder, the first commercially available 1992 model. Today I’ll tell you about impressions, about other available versions of devices (and there were surprisingly many of them), and I will touch on a topic that dramatically complicated Philips’s life. The fact is that, unlike the minidisk, DCC had backward compatibility: on all devices you can play regular audio tapes. The difficulties associated with supporting such a harsh legacy, it seems to me, have exceeded the benefits of compatibility.

I keep a diary of a collector of old pieces of iron in real time in a Telegram .

About the DCC format, less information is available than about the minidisk. Unfortunately, there is no evidence from the developers - it would be interesting to know how and why they made certain decisions. There is a lot of information on device repair on the DCC Museum Channel : but there you will find more likely instructions for repairing models available for sale. In June, the creators of the museum are planning the premiere of a documentary about a digital cassette.

Why did Philips go all the way to storing digital audio on tape? The obvious answer: the same Dutch company created a compact cassette in the sixties. One source mentions negotiations between Sony and Philips on working together on a digital rewritable medium, but for some reason, the two companies did not continue collaborating on the development of the CD in the early eighties. My guess: the cassette was chosen as the cheapest medium, the production technology of which has already been worked out.

On the left is a digital cassette with a shielded security shutter, in the normal position completely covering the tape. On the right is a regular cassette.

Then I forgot to rewind a regular cartridge, you have to take a word: the chemical composition of magnetic tape is different from that of a conventional cartridge. The tape in DCC media is either very similar in composition or identical to tape in video cassettes. At DCC, metal guides are still noticeable where the magnetic head contacts the tape: together with the counterpart in the tape recorder, they fix the tape relative to the head. The tape winding holes are located only on one side of the cassette: auto-reverse is a mandatory feature, and you do not need to turn the cassette over.

Then the difficulties begin. Both the DCC format and the cassette were preceded by the Digital Audio Tape format, which uses a rotating head for reading and writing, as in VCRs. This design allowed us to record more data on the same area of the tape, but it was more difficult and more expensive to implement (and certainly not compatible with old cassettes). In DCC, data is written to the cassette in several parallel tracks: there are eight in total on each side, plus an additional ninth track for related data - time markers, identifiers for starting a new track and text information.

As a result, a magnetic head for reading and writing is almost the most innovative element of Philips DCC technology. In my Philips DCC900, the magnetic head is actually a 20-head sandwich: 9 for reading, 9 for writing, and two more for reading traditional CDs. In the latest portable devices, the head did not rotate, reading and writing on both sides of the tape was provided by a double set of heads - only forty pieces.

DCC data is staggered at a bit rate of 768 kilobits per second. Taking into account the data for error correction (it is provided both by a tricky distribution of data on tracks and by Eight-To-Fourteen conversion , as in CDs), the real bitrate is 384 kilobits per second or 260 megabytes for a 90-minute cassette. This is slightly larger than the minidisk (there were 292 kilobits in the original version of the format). To store audio, respectively, lossy compression is required. Philips used the minimally modified standard Mpeg-1 Layer 2, which was also used on Video CDs. There is a curious articlein Stereophile magazine for April 1991. The correspondent who visited the Philips prototype was not able to distinguish between the sound of the “compressed” sound of a digital cassette and the original on a CD. Given that Stereophile has always been and remains a magazine for audiophiles, this is serious praise. The first-generation Sony Minidisc compression artifacts were audible even to those who did not have golden ears, and in this sense, Philips gained an advantage.

Philips did a lot to promote the format, and it did better than its competitor. Contracts were signed with independent music studios, at the time of the start of sales an extensive catalog of recording tapes was immediately available. In music and simply popular publications in the USA of those years, I found DCC ads (as in the picture above) more often than minidisc ads. Everything seemed to go according to plan. Why didn’t it work out? To answer this question, I needed to purchase a live device and test the format on myself.

Philips DCC900 was released in 1992, and what a hell, he is huge. Unlike Sony, which immediately bet on portable, portable players for digital cassettes appeared only in the next, 1993. For comparison, I placed a Kenwood minidisk deck on top, but it was made rather large for beauty: inside it is quite empty. But Philips is not so.

On the main board below is located mainly the analog part. The digital one is hidden under a metal screen, and two more boards are mounted on a cassette mechanism.

Prototypes of Philips DCC tape recorders have been designed for vertical cassette installation. Almost all real devices have a slot drive, almost like a CD. The ninetieth series of Philips devices in the nineties was the most top-end: you could assemble a set of a CD player, tuner, amplifier, DCC recorder, and all of them could be controlled via a common bus. The price of a digital tape recorder came out rather big - $ 800 in the United States. Cassettes sold for $ 8-10, slightly cheaper than mini-discs at the dawn of the format. At some point, the expected savings on cheap media disappeared somewhere. But on digital tapes it was immediately possible to record 90 minutes of music, while the first minidiscs were 60 minutes.

Okay, let's try to record something. Like minidisc devices, the DCC900 can record from analog and digital inputs. First-generation devices could process 16-bit digital sound, in later models the dynamic range was expanded to 18 bits - however, the minidisk also learned how to do this in 1996. The tape recorder writes the so-called lead-in on an empty cassette - essentially a marker indicating that the data starts here. From this point, during further recording on the very ninth track with data, an absolute timer begins to be recorded. If there was already a recording on the tape, the tape recorder searches for an existing marker and plays a piece of the old one before starting a new recording - what if there is something valuable there? Then everything is simple: we write a sound, if necessary we stop it. The tape recorder always rewinds the tape so that the next track starts exactly there, where the previous one ended. If necessary, press the button on the remote control or on the device itself to indicate a new track.

Difficulties begin when you reach the end of the tape. Here, the developers have provided two options. Where you find that enough content for the first side, you can put one of two markers. In one case, seeing the desired marker, the tape recorder stops playback (or recording), winds the tape to the end, and starts a new track on side B. In another, the tape recorder instantly switches to the second side. This option leads to the loss of several meters of tape both on the one hand and on the other, but switching between tracks on different sides is as quick as possible (but there is still a delay). Compare this with a minidisk - there is basically no such problem.

I have long wanted to buy the same album on different media. Albums on DCC are now rare: the tape on the left cost me 10 times more than the tape on the right, or CD .

First-generation tape recorders did not know how to write track names, artist names, and album names onto a cassette. In general, if you insert a self-recording cassette into the DCC900, it only shows the absolute time during playback. The track number will be displayed when you reach the nearest marker. Therefore, cassettes with music from the store are the only way to appreciate the format in all its beauty: here is text information (there was even a plan to record the lyrics of the songs), and, most importantly, data on all tracks are continuously recorded on the data track. At any time, you can select any track on the album, and the tape recorder will rewind the tape and, if necessary, switch between the parties. Again, the advantage of the minidisk is obvious: it has a table of contents where you can write all the information,

All this cassette laziness was normal in the analog era, but compared to CD, the DCC standard was seriously losing. Want to switch to a new track? Wait. Want to erase an existing marker? First find it, then wash it. If 10 tracks were recorded on the cassette, and then the part was re-recorded again, you had to activate a separate feature that scrolled the entire tape in search of markers and changed the track numbers, if necessary.

Some of the shortcomings of the first generation tape recorders were fixed in devices released later. In the second generation, the cassette mechanism was completely redone: the carrier was now inserted sideways. They released portable players: they weighed a pound, worked on a proprietary battery and did not know how to record. In the third-generation devices, the jambs were fixed. The last Philips DCC951 stationary tape recorder was able to rewind the tape from beginning to end in a minute, supported 18-bit sound, and let you enter the names of tracks and albums.

Philips DCC170 and 175 portable players were relatively compact and supported recording, including from digital sources. The most interesting portable model is the Philips DCC175. Using an optional cable, it could be connected via a parallel port to a computer. The software supported Windows 3.1 and Windows 95. It was possible to write data (250 megabytes to a 90-minute medium) and music onto a cassette, along with track names and navigation. Unlike Sony, Philips was not worried about protecting the data compression format - it was already half-open anyway. Modern releases on DCC cassettes (a couple of albums released last year) are written on a modified version of DCC175.

Unfortunately, this is the most difficult to collect artifact. Portable players, designed and manufactured not by Philips, but by the Japanese partner Matsushita, generally sold a little. A DCC175 was sold only in the Netherlands, and the optional interface cable to it was generally released in a circulation of 1000 pieces.

In 2019, I acquired a digital tape recorder, planning to experiment with the format, and to listen to ordinary audio tapes. And what? A convenient device with a remote control and auto reverse, the most for playback, and you can record on another technique. Alas, I failed to investigate this use case normally - the whole thing is in leaking capacitors. For those two boards, mounted on the DCC900 mechanism itself, SMD capacitors were used for compactness, which in all tape recorders of this series follow over time. I bought a tape recorder as a “serviced” one, but alas, the previous owner replaced the capacitors only on the board responsible for the digital signal. The analog channel simply does not work normally - the sound of one channel is missing, in the second it is very distorted. Have to solder. In general, the test of time minidisc survived better than DCC. This stems from the bet on the cassette: in each device, it is necessary to replace the drive belts, and in my case also change the capacitors. Finding a mini-CD deck in working order is much easier, and the mini-discs themselves are generally unkillable. In the early DCC cassettes, the unsuccessful material of the pad used to press the tape to the head was used, they not only creak terribly, but they also do not read plainly - the tape moves in jerks.

Why did the format fail? Previously, competition with Sony was considered the main reason. In the home digital audio market, there was a typical format war, a battle similar to VHS vs. Betamax or Blu-ray vs. HD DVD. In fact, almost all storage media have gone through this stage, including even a compact cassette, but excluding a CD. One of the two formats was doomed to failure, but now we know that absolutely all physical data carriers were doomed. Both minidisk and DCC lost to cheap CD-R discs and file-sharing networks. Philips did the right thing, fixing the losses, while Sony decided to continue investing in a hopeless format, which, admittedly, was still more convenient than a digital cassette.

There are two things that interest me in DCC history. First, was it possible to avoid such a failure and not invest in the development of a digital cassette at all? It is unlikely that such complex projects lasted for many years, and they began in the mid-late eighties, when there were far from penny blanks, computers were low-powered, and the web did not exist at all. At the same time, there is an increase in sales of CDs, and in general, everything is digital, and analog is considered obsolete. It is curious that since then the situation has turned 180 degrees. If you behave carefully, you can finally give up the initiative to competitors and go bankrupt. If you want, you don’t want, but you have to take risks.

Secondly, my introduction to DCC shows that legacy support sometimes brings more problems than solutions. I’m already fantasizing here, but in theory, what prevented writing data on a tape in only one direction? Thus, simplifying the mechanism: you do not need auto-reverse, you do not need to invent complex ways to switch from one side to the other, there is no inevitable pause between tracks. But then the backward compatibility that marketers had relied on would be lost. I myself prefer formats or services that remain compatible with legacy devices for as long as possible. But the example of a mini-disk shows that sometimes it is worth abandoning a difficult heritage and making it really more convenient and compact.

Наконец, DCC показывает, что продукт может быть неудачным и рано сойти со сцены, но технологии, лежащие в его основе, останутся жить. Технология создания магниторезистивных головок для цифровой кассеты была позаимствована из жестких дисков, и скорее всего новые наработки нашли применение в дальнейшем. На википедии упоминается анекдотический пример применения технологии создания головок для магнитофонов DCC в фильтрах для пива. И DCC, и минидиск внесли свой вклад в развитие сжатия звука с потерями на раннем этапе, и теперь мы косвенно используем эти наработки и при послушивании музыки, и при беспроводной передаче на наушники и через сеть.

In my case, DCC was the first format that I acquired purely for study: there could be no nostalgic background here. I decided on this experiment only because of compatibility with a traditional audio cassette. If I manage to change the capacitors, and if the board was not killed by leaking acid, I will have a backup tape recorder. Fans of a digital cassette (such also exist) strongly recommend that these devices not be used in this way - old cassettes much more quickly get their heads and pressure rollers dirty. But I probably won’t listen to their advice. In the end, we only live once.