Security Week 14: ShadowHammer and supply chain

Last week's main news is a targeted attack on owners of Asus devices through the hacked utility Asus Live Update. Kaspersky Lab researchers found an attack in January this year: an infected utility for updating drivers on laptops and computers with Asus components was signed with a legitimate certificate and distributed from the manufacturer’s servers. Modification of the utility provided crackers with full access to all affected systems, but they used this opportunity only when the MAC address of one of the system’s network adapters matched the list of systems of interest.

In this case, additional malware was downloaded from the server created in March 2018 and stopped working before the attack was detected - for the time being for unknown purposes. The attack is notable for its complexity and stealth. Most likely, it was preceded by larger-scale events with the aim of collecting information and identifying “promising” victims. Although it’s too early to talk about the exact attribution of an attack, there is evidence linking it with earlier incidents with the 2017 CCleaner utility . A full investigation of the attack will be published next week and presented at the Kaspersky Lab conference Security Analyst Summit . In this post - a brief description of the incident and some conclusions.

Primary Sources: news ,excerpts from a Kaspersky Lab study, a detailed article on Motherboard , an official Asus statement . You can check the MAC address of your Asus device using this online service.

From June to November 2018, an infected version of the Asus Live Update utility was distributed from Asus servers. The program is preinstalled on laptops of this manufacturer, but is also available for owners of computers based on Asus motherboards. It allows you to download the latest BIOS, firmware and device drivers and install them automatically. The malicious application was uploaded to the vendor’s servers, signed by the company's legitimate certificates, and it was distributed as an update to the program. Reddit has a discussion of the strange behavior of the utility, although it has not yet been established whether the incident mentioned in the thread is associated with this attack.

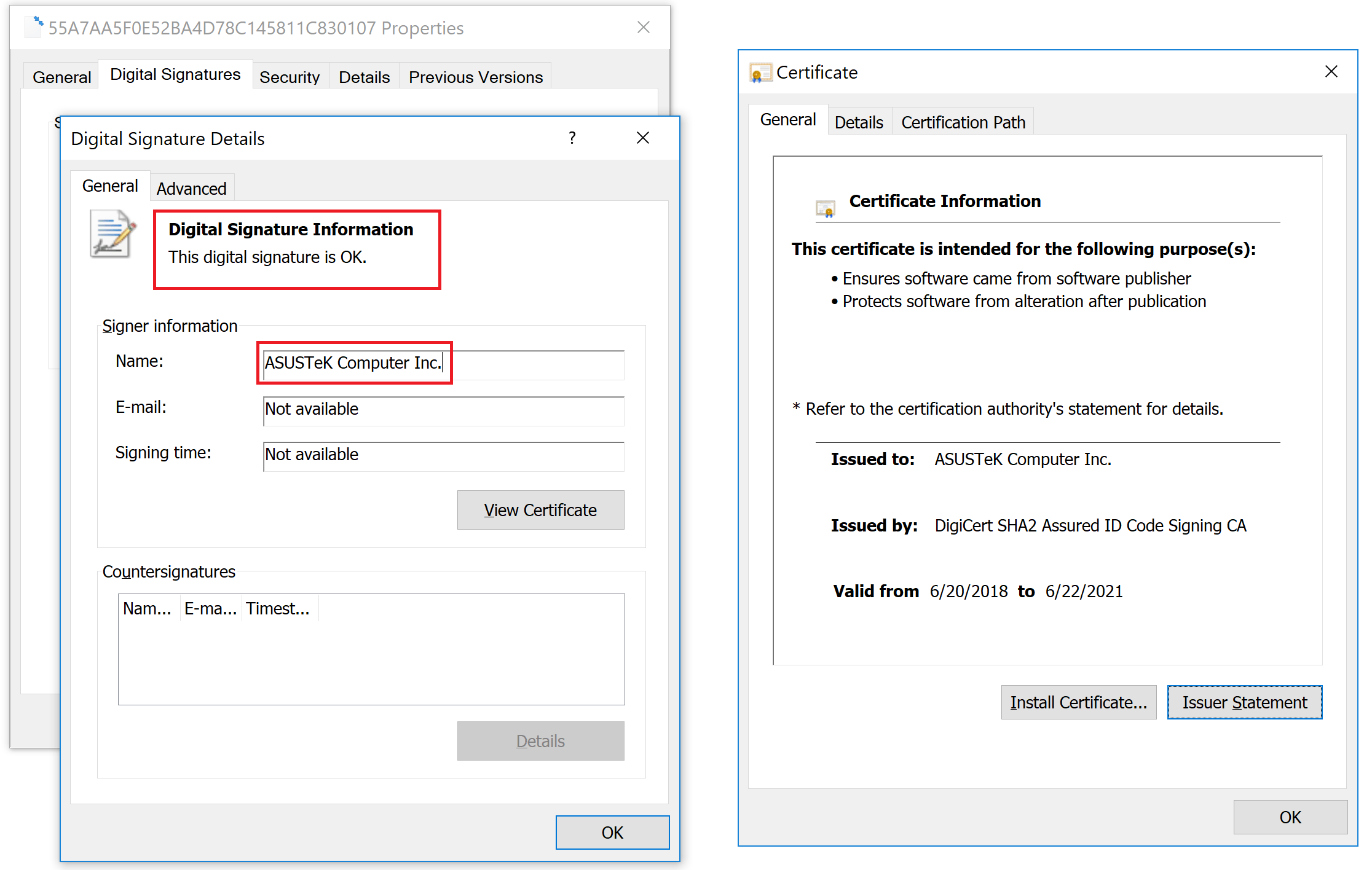

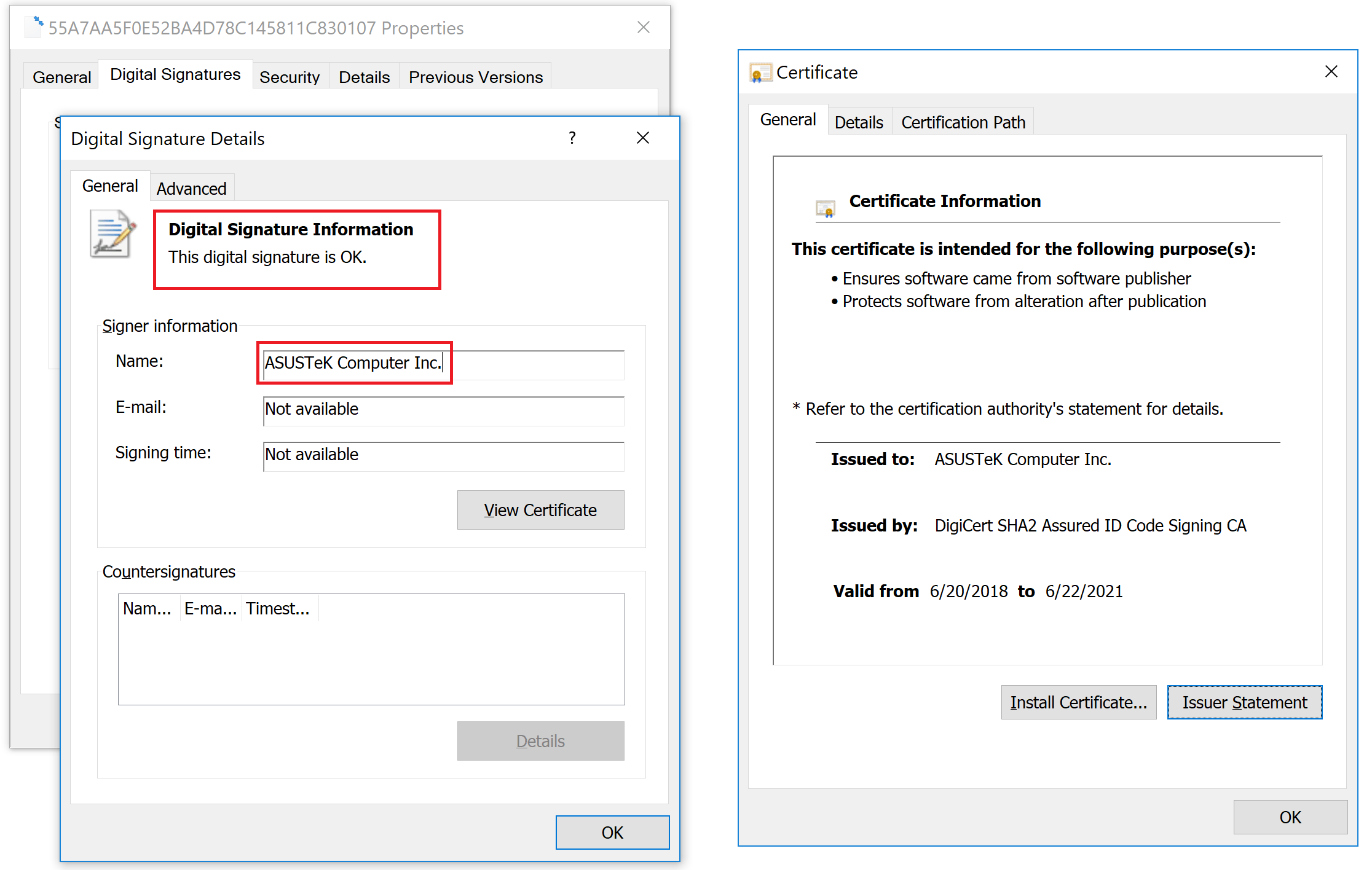

Although the utility was “updated”, in fact it was an outdated version of the program with additional malicious functionality (an analysis of malicious code by an independent researcher is here) It can be concluded that the Asus infrastructure was partially compromised: the attackers had access to the update server and digital certificates, but not to the application source code and build servers. Detection of a malicious utility was made possible thanks to tests of a new technology aimed at detecting attacks in the supply chain (in English - the supply chain) - when attackers either somehow attack software or hardware before being delivered to the final consumer-victim, or they compromise the service tools and device management during operation - those that are customary to trust.

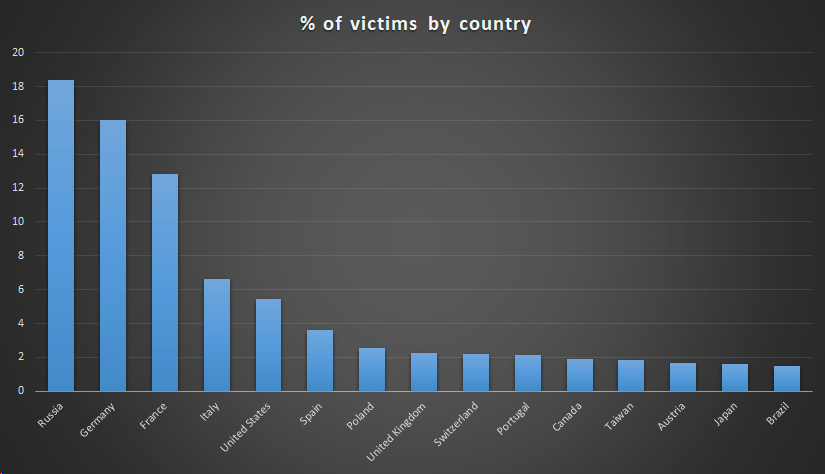

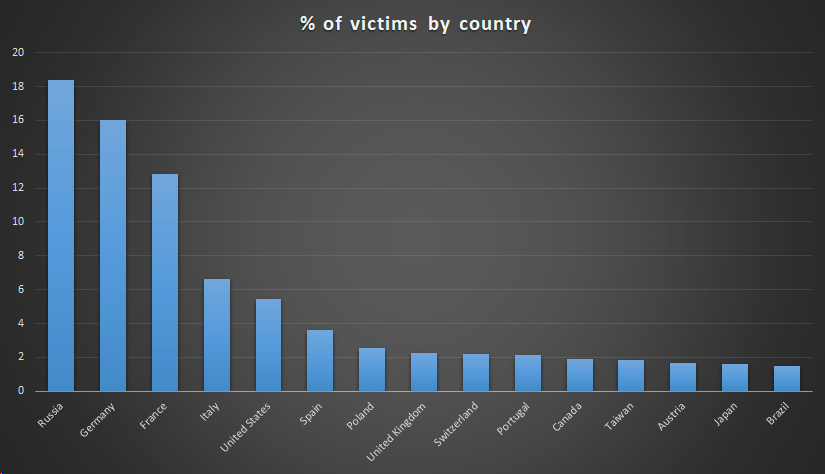

If you count all those who flew the utility "with an appendage", then tens of thousands of users were affected, most of them from Russia, Germany and France. But this is only according to Kaspersky Lab. Later, Symantec provided its own data - they counted 13 thousand infected systems, with a larger share of US users. This is clearly not all affected, most likely the malware was on hundreds of thousands of systems. But on most attacked computers, the utility did nothing, it only checked the MAC addresses with its own database. In case of coincidence from the command server (the domain asushotfix [.] Com was registered for it), additional software was loaded. In some cases, the trigger was a combination of the MAC addresses of the wired and wireless network modules.

From two hundred samples of the infected utility, we managed to extract about 600 MAC addresses of the systems that the ShadowHammer attack was really aimed at. What was then done with them is not yet clear: the command server stopped working until the researchers discovered the attack. Known facts end there, conclusions begin.

The complexity of the attack is now hardly anyone to be surprised by - there are examples of targeted attacks with much more serious investments in R&D. An important feature of the ShadowHammer operation is that it is a successful supply chain attack. The infected software is distributed from the manufacturer’s servers, signed by the manufacturer’s certificate - on the client side there is no reason not to trust such a scenario. In this case, we are dealing with a preinstalled utility, but earlier other programs that the user usually installs on his own were also successfully attacked. Kaspersky Lab experts have reason to believe that the fresh ShadowHammer attack is related to two incidents two years ago.

In the first case, the CCleaner utility mentioned above was modified, it was also distributed from the manufacturer’s servers. In the second case, it was attacked by a software vendor to manage devices in the corporate network NetSarang. It is possible that there were other attacks during which attackers collected the MAC addresses of computers of interest to the victims. In this story, there is a hint of one of the real reasons for the mass infection of IoT devices - IP cameras, routers and the like. It is not always possible to get to the data of interest through an infected device, but enough information can be collected for use in the next, more targeted operation.

Of course, the question arises of trust in the manufacturers of hardware and software: if a software update or driver arrives from a vendor, is it safe or not? Perhaps you still need to trust, otherwise the point of vulnerability may simply move to another place. A prompt response to such incidents by the manufacturer is also welcome. In the case of Asus, according to Kaspersky Lab, almost two months passed from the first notification (end of January) to the official confirmation of the problem (March 26). I wonder what technologies will be used to quickly detect such attacks? There is something to work on for both manufacturers of security software and vendors. There are only a few cases of using a legitimate certificate to sign malware,

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this digest may not always coincide with the official position of Kaspersky Lab. Dear editors generally recommend treating any opinions with healthy skepticism.

In this case, additional malware was downloaded from the server created in March 2018 and stopped working before the attack was detected - for the time being for unknown purposes. The attack is notable for its complexity and stealth. Most likely, it was preceded by larger-scale events with the aim of collecting information and identifying “promising” victims. Although it’s too early to talk about the exact attribution of an attack, there is evidence linking it with earlier incidents with the 2017 CCleaner utility . A full investigation of the attack will be published next week and presented at the Kaspersky Lab conference Security Analyst Summit . In this post - a brief description of the incident and some conclusions.

Primary Sources: news ,excerpts from a Kaspersky Lab study, a detailed article on Motherboard , an official Asus statement . You can check the MAC address of your Asus device using this online service.

What happened

From June to November 2018, an infected version of the Asus Live Update utility was distributed from Asus servers. The program is preinstalled on laptops of this manufacturer, but is also available for owners of computers based on Asus motherboards. It allows you to download the latest BIOS, firmware and device drivers and install them automatically. The malicious application was uploaded to the vendor’s servers, signed by the company's legitimate certificates, and it was distributed as an update to the program. Reddit has a discussion of the strange behavior of the utility, although it has not yet been established whether the incident mentioned in the thread is associated with this attack.

Although the utility was “updated”, in fact it was an outdated version of the program with additional malicious functionality (an analysis of malicious code by an independent researcher is here) It can be concluded that the Asus infrastructure was partially compromised: the attackers had access to the update server and digital certificates, but not to the application source code and build servers. Detection of a malicious utility was made possible thanks to tests of a new technology aimed at detecting attacks in the supply chain (in English - the supply chain) - when attackers either somehow attack software or hardware before being delivered to the final consumer-victim, or they compromise the service tools and device management during operation - those that are customary to trust.

Who hurt

If you count all those who flew the utility "with an appendage", then tens of thousands of users were affected, most of them from Russia, Germany and France. But this is only according to Kaspersky Lab. Later, Symantec provided its own data - they counted 13 thousand infected systems, with a larger share of US users. This is clearly not all affected, most likely the malware was on hundreds of thousands of systems. But on most attacked computers, the utility did nothing, it only checked the MAC addresses with its own database. In case of coincidence from the command server (the domain asushotfix [.] Com was registered for it), additional software was loaded. In some cases, the trigger was a combination of the MAC addresses of the wired and wireless network modules.

From two hundred samples of the infected utility, we managed to extract about 600 MAC addresses of the systems that the ShadowHammer attack was really aimed at. What was then done with them is not yet clear: the command server stopped working until the researchers discovered the attack. Known facts end there, conclusions begin.

The complexity of the attack is now hardly anyone to be surprised by - there are examples of targeted attacks with much more serious investments in R&D. An important feature of the ShadowHammer operation is that it is a successful supply chain attack. The infected software is distributed from the manufacturer’s servers, signed by the manufacturer’s certificate - on the client side there is no reason not to trust such a scenario. In this case, we are dealing with a preinstalled utility, but earlier other programs that the user usually installs on his own were also successfully attacked. Kaspersky Lab experts have reason to believe that the fresh ShadowHammer attack is related to two incidents two years ago.

In the first case, the CCleaner utility mentioned above was modified, it was also distributed from the manufacturer’s servers. In the second case, it was attacked by a software vendor to manage devices in the corporate network NetSarang. It is possible that there were other attacks during which attackers collected the MAC addresses of computers of interest to the victims. In this story, there is a hint of one of the real reasons for the mass infection of IoT devices - IP cameras, routers and the like. It is not always possible to get to the data of interest through an infected device, but enough information can be collected for use in the next, more targeted operation.

Of course, the question arises of trust in the manufacturers of hardware and software: if a software update or driver arrives from a vendor, is it safe or not? Perhaps you still need to trust, otherwise the point of vulnerability may simply move to another place. A prompt response to such incidents by the manufacturer is also welcome. In the case of Asus, according to Kaspersky Lab, almost two months passed from the first notification (end of January) to the official confirmation of the problem (March 26). I wonder what technologies will be used to quickly detect such attacks? There is something to work on for both manufacturers of security software and vendors. There are only a few cases of using a legitimate certificate to sign malware,

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this digest may not always coincide with the official position of Kaspersky Lab. Dear editors generally recommend treating any opinions with healthy skepticism.