Want to be a little happier? Try to be the best in your field

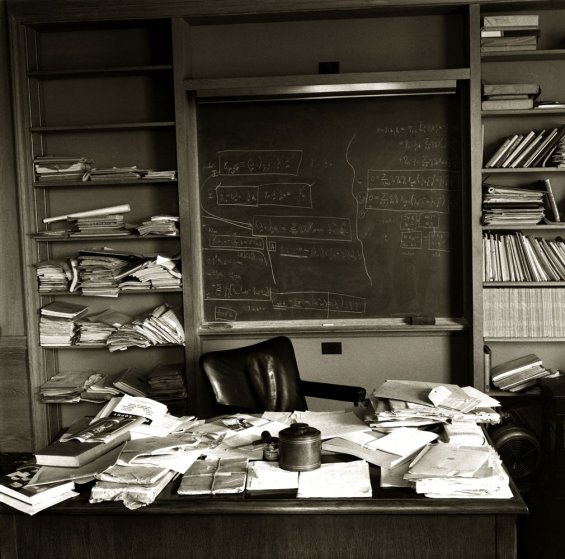

This is a story for those whose only resemblance to Einstein is the mess on the desktop.

The desktop photo of the great physicist was taken a few hours after his death, on April 28, 1955, in Princeton, New Jersey.

The Myth of the Master

The whole culture created by man is based on archetypes. Ancient Greek myths, large novels, “Game of Thrones” - the same images, or in the expression of an IT language, “patterns”, we meet again and again. This thought itself has already become a commonplace: the author of the book “A Hero with a Thousand Faces” and numerous postmodernists who began to weave long-told stories like biblical stories and the same myths about Zeus drew attention to the existence of a single ground for the roots of all the stories of the world, Hercules and Perseus in new contexts.

One of these archetypes is a person who has mastered his craft perfectly. Virtuoso. Guru. Bulgakov, in his most famous novel, called such a hero bluntly - the Master. The first example that comes to mind is a brilliant detective who is able to investigate a case and find a criminal in several seemingly unrelated, very indirect evidence. This is such a hackneyed plot that it would seem: while it may be interesting to read / watch from the screen? But you must admit: such a story does not cease to be interesting. And this means that for some reason we are worried about the image of a man who has reached perfection in his craft.

In fact, this archetype is one of the most exciting for us, even if we are not always ready to admit it to ourselves. Only in recent weeks have I been a participant in a conversation about skill twice. In the first case, I watched a rather typical but very exciting action movie about a genius detective, and I heard from one of the neighboring places: " I also want to understand my profession like he does ." In the second case, one of my comrades began to discuss the topic of the fact that someone on your way will always come across someone who knows your business better than you. These living reactions and conversations from real life show how strong we have in us the desire to become the best in our field. But how to do that? And why? Let's try to figure it out.

How a feeble guy became a “Wizard”

Returning to the question of detectives. In my other article, I have already examined the question of what role erudition plays in our lives. And as an example, he cited the terms of reference of Sherlock Holmes described in “A Study in Scarlet” - a detailed list (given at the very beginning of that article) was compiled by the notorious Dr. Watson, a friend of Holmes. As we can see, Holmes's erudition was not wide - but on the other hand, his knowledge in the fields adjacent to his immediate profession was extremely deep. He was interested in everything that could ever theoretically help him attack the trail. And the rest he left behind his attention.

Why is this moment so important? Because it gives the key to unraveling the Sherlock phenomenon. So why did he achieve such significant success in his business? Was he born genius? No, he just became a virtuoso through continuous work on himself.

I want to tell the story of an athlete who, being one of the most successful Russian players in the National Hockey League (North America), was recognized as one of the hundred greatest players in this league. The only hockey player in the world to win the Olympics, World Cup, Stanley Cup and Gagarin Cup. These are dry encyclopedic facts. But in order to understand what is the true greatness of this player, it is better to just watch a few moments of his game. So, get acquainted - Pavel Datsyuk, whom the NHL colleagues nicknamed “The Magic Man” (“Wizard”), as well as “Houdini” (“Houdini”, by the name of one of the greatest magicians in history).

Did you see how cleverly he outlines three or four opponents? Or how does he make the goalkeeper nervous on a series of shootouts (an analogue of football “penalty kicks”)? What speed and plasticity moves?

Datsyuk is interesting not just because he plays cool. His playing style is marked by two things. Firstly, he plays smartly. He not only knows how to calculate the course of the game, but is also a good psychologist. Datsyuk can cause the enemy to fall without touching him. Secondly, he simply masterfully owns his club and skates. This is what allows him to score, for example, even being behind the goal line (from a negative angle). And as we can see from the next video, this is not just a natural gift - it is the result of focused training.

Pavel is not a very hockey player, unlike, say, Ovechkin and Malkin, who are more by ear. And he clearly did not have an innate talent: as a child he was not considered a talented hockey player, and he got to the NHL draft (annual selection of young players in the League) at number 171 - that is, very far from the best rookie of that year. Many at first did not understand, what is he doing all this on ice! Until in his third game year he tripled the number of goals scored per season. And all this tells us that the “Wizard” really trained himself. I think that during training, he simply set himself new goals, constantly provoking himself to continuous improvement. Otherwise, he would not have been so masterful in owning the puck and moving so gracefully on ice. He himself only joked in an interview with American journalists that in his youth in Russia he had money for only one puck, so he had to learn to own it for as long as possible.

Why strive to be the best?

Datsyuk is just one example of how a person can achieve extraordinary results in his beloved business through self-improvement. At the beginning of the article, we talked a lot about literature - let's recall the writer Nabokov, who wrote his most famous work, Lolita, in English, and only then translated it into Russian. Can you imagine that a person whose native language is Russian should learn French enough to think in it, and English to write novels? I have been living abroad for 8 years, and life still regularly throws me into the fire of shame from my own vocabulary. But language is not my profession. Unlike Nabokov.

Success in the profession is actually more important than we think. And it is measured not only by money. I would even say that money can bring down a compass of professional goals, which can be directed to another north. I don’t want to be unsubstantiated, but now I can’t just give studies that show that employee motivation is determined not only by monetary incentives (if you wish, you can rummage through archives of publications like the Harvard Business Review). To get job satisfaction, we need something else. And that other north may be the desire to become the best in their field. And given that we spend most of our lives (excluding sleep time) at work, it would be nice to feel satisfied at work and in the profession as a whole.

People throughout their existence try to find happiness. Even the Ukrainian philosopher Skovoroda in the distant 18th century realized that happiness in life comes from happiness in work (and probably not even he was the first who thought of it before): “ To be happy means to know yourself and your nature, to take for your share and do your thing". Do not take this urge as a universal truth or an excellent formula for solving all problems. But it seems to me that if we aim at constant professional self-improvement, then it is really possible that we can become a little happier. By setting a high bar and conquering it again and again again, we can get more joy from work. Perhaps this will add to our peace of mind (because we will have our own sweet harbor), self-confidence, and even a feeling of gratitude. In the book "Samurai without a sword" It is called about a Japanese samurai, which eventually became the ruler of the country, but it started with the fact that just brought a slipper their overlord - and even this duty he tried to execute better than anyone how to be funny as it may sound to us.

I do not just use the word "craft". Work is rarely spectacular. Basically, this is a difficult and rather boring routine.

The path to becoming the best is not easy. The human brain is designed to follow the path of least resistance. He likes to receive immediate rewards. And therefore, on the way to conquering the peaks, you will have to exert all your will. But trying to do what you do is good, you can make it a habit - after all, the brain is prone to get used to it.

They say that now humanity is going through the "era of daffodils." And the desire to become the best in his profession is especially given away by undisguised vanity and narcissism. Well, let it go! Let's confess to ourselves: it’s nice to feel our own superiority. If only it was justified, and did not take the ground underfoot. And there is no doubt: sooner or later there really will be someone who will still be better than you. And this will only mean that it is too early to stop on the spot.

I don’t know how to find “my” craft. They say that "the desire to understand what I want is a trap "; that " sitting, thinking, sorting out and understanding what you really want is practically impossible ." Others consider, that it’s enough just to ask the right questions like: if you only have a year left to live: how will you spend it? If you had enough money for a life, what career would you choose? I don’t know who is right, and I really don’t know how they find the cause of their life. But I saw people whose eyes burn from the process of work. And he saw live hockey players of one now not very successful club, who could barely crawl on the ice with indifferent faces, hopelessly losing to a weak opponent. “Do they really not want to play better?”, I only thought at that moment.

This is not only a story about work. It’s all about life. Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic movement, proclaimed: “Faster, higher, stronger.” It doesn’t matter what you do - you program, score goals, write texts or simply cook dinner for your beloved - try to do it like the best. And the point is not that you really have to become the best. And in order not to stand still, not to get bogged down and enjoy working. It is not about becoming - it is about striving. And even if you are not a genius at all, and your only resemblance to Einstein is a mess on the table, then remember that there was a guy who started 171st, but became the first.