Zebra stripes - it is a no-fly zone for midges

- Transfer

In our modern age of rapid development of IT-technologies, it seems that we already know everything and there is not a single secret in the world. Why the wind blows, why the bun is round, even why the natives ate Cook - almost every person knows.

But why zebras are striped , probably not many guess at all. Nevertheless, they ALREADY found out ...

The following is a translation of an article that scientific testing has shown the benefits of a striped zebra coat.

Zebras are famous for their contrasting black and white stripes - but until recently no one knew why they wear their unusual striped pattern. This question was discussed 150 years ago by great Victorian biologists such as Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace.

Since then, many ideas have been put forward, but only in the last few years have serious attempts been made to test them. Existing ideas can be divided into four main categories:

- zebras are striped to avoid capture by predators;

- striped zebras for social reasons;

- zebras are striped to keep cool;

- stripes help them avoid midges bites.

And only the last of them passed the test. And our latest research will help fill the gaps in your knowledge with a large number of details about why.

Fig_1. Camouflage? Identification? Natural conditioner? No, no and NO.

What is the use of zebra stripes?

Can stripes help zebras not become predator food? This idea has many problems. Field studies show that zebras, even in poor light, are easily distinguished by the human eye. When they are among trees or in pastures, they look far from disguised . And fleeing from danger, zebras do not behave in such a way as to increase confusion, possibly caused by stripes, which makes hypothetical ideas about stunned predators untenable .

Even worse, the sight of lions and spotted hyenas is much weaker than ours. These predators can distinguish stripes only when zebras are very close, at a distance when they are likely to hear and smell prey. Thus, stripes are unlikely to be useful for protection against predators .

Most of all, this idea is undermined by the fact that zebras are the preferred prey for lions - in a study after examining all of Africa, it turned out that lions kill them more than might be expected from their abundance. Thus, the stripes cannot serve as a very effective protection against predators of this important carnivore. So much for the hypothesis of evading predators.

What about the idea that stripes help zebras interact with representatives of their own kind? Each zebra has a unique stripe pattern. Could this be useful for individual recognition? Such an opportunity seems unlikely, given that evenly colored domestic horses can recognize other individuals by sight and sound . The striped members of the horse family do not look after each other as a form of social connection, more than the non-bandwidth species of horses. Moreover, very rare hairless representatives of zebras do not shun members of their group , and they successfully breed.

How about protection from the hot African sun? Since it can be expected that the black bands absorb radiation and the white ones reflect it, one of the ideas was that the bands create convective flows along the back of the animal, cooling it.

Fig_2. Field experiments checked how different coloration affects the temperature of barrels filled with water.

Again, that seems unbelievable: rigorous experiments in which large barrels of water were draped in striped or uniform colored skins, or were painted in stripes or continuously, showed no difference in the temperature of the internal water . In addition, the thermographic measurements of zebras, impalas, buffaloes and giraffes in the wild show that zebras are no colder than other species with which they live.

The last idea regarding stripes sounds ridiculous at first glance - stripes stop bloodsucking insects from getting blood - but it has great support.

Early experiments in the 1980s showed that tsetse flies and horseflies evaded landing on striped surfaces , and were recently confirmed .

The most convincing, however, are data on the entire geographical range of the seven existing animal species. Some of these species are striped (zebras), some are not (Asian donkeys), and some are partially striped (African wild donkey). For different species and their subspecies, the intensity of strip alternation is closely related to midges bites in Africa and Asia. Thus, wild animals living in areas where midge irritation continues throughout the year are most likely to have noticeable striped patterns.

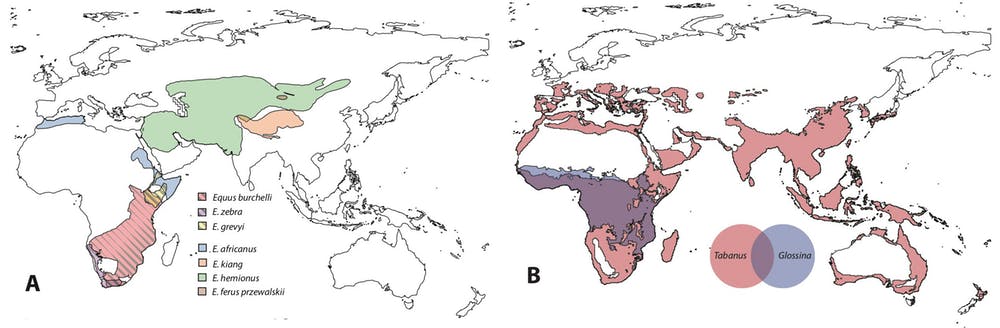

Fig_3. Map A on the left shows where the living animals are striped or smoothly colored. Map B on the right highlights the distribution of tsetse flies (Glossina) and areas where the horse fly (Tabanus) bites for seven consecutive months each year.

We believe that the reason animals should be striped in Africa is because African midges carry diseases such as trypanosomiasis, African horse plague, and horse flu, which can be fatal to animals. And zebras are especially susceptible to attempts to bite midges in the oral cavity due to their short, furred hair. Having a fur pattern that would help to avoid midges and the deadly diseases that they carry would be a strong advantage, meaning that the stripes will be passed on to future generations.

Testing the idea that stripes and flies don't mix

But how do stripes actually affect midges? We set off to explore this at the stable in Somerset, UK, where horseflies are collected in the summer.

We were lucky to work with Terry Hill, the owner of the stable. We were able to get very close to his horses and tame the flat zebras, which allowed us to actually observe midges, landing or flying horses. We also videotaped the behavior of midges around the horses and wore colorful capes on them.

Fig_4. Uniformly colored horses received much more approaches and touchdowns from annoying midges than zebras.

It is important to remember that flies have much worse vision than humans. We found that zebras and horses received the same number of approaches from horseflies, probably attracted by their smell, but zebras experienced much less landings. Around the horses, flies hover, curl and turn before landing again and again. On the contrary, near the zebras flies either flew past them, or made the only fast landing and again flew away.

Frame-by-frame analysis of our videos showed that the flies smoothly slow down when they approach brown or black horses before making a controlled landing. But they did not slow down when approaching zebras. Instead, they flew past or literally crashed into an animal and bounced off.

Fig_5. Striped cloaks on solid horses reduced the number of flies on covered parts of the body.

When we placed black or white capes or striped capes on the same horse to control any differences in animal behavior or smell, again the flies did not land on the stripes. But there was no difference in the speed of landing on the bare head of a horse, showing that the strips had their effect near, but did not impede approach at a distance.

And this showed us that the striped capes that are currently being sold by the two companies really work.

So, now that we know that the stripes affect horseflies very close, and not at a distance, what actually happens in inches from the host? One idea is that the stripes create an optical illusion that violates the expected pattern of movement of the fly when it approaches a zebra, preventing it from landing correctly. Another idea is that flies see a zebra not as a solid, but as a series of thin black objects. Only when they are very close do they realize that they are going to hit a solid body and deviate instead. We are now considering these possibilities.

Thus, our basic study of flies behavior not only tells us why zebras are so beautifully striped, but also has real implications for the equestrian industry, with the potential to make riding and keeping a horse less painful for the horse and rider.