Metropolis Modeling

- Transfer

One of the most iconic games of all time is based on the theory of how cities die, which suddenly turned out to be too influential.

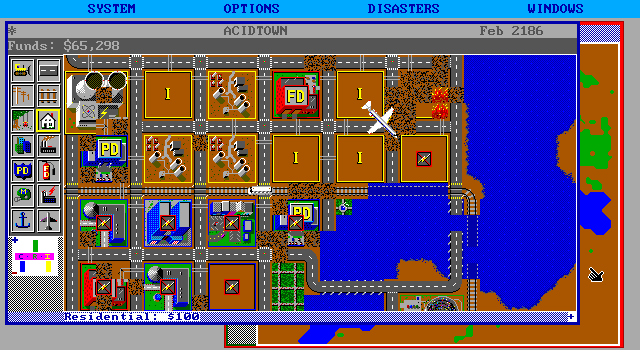

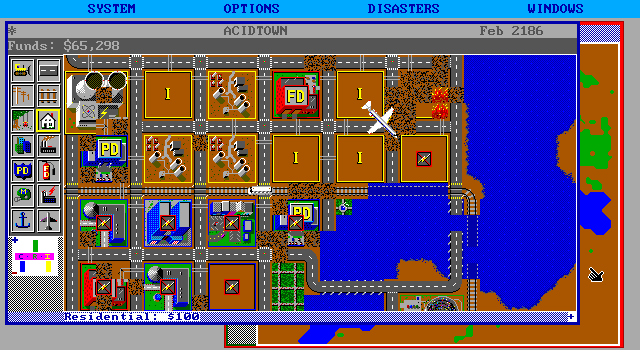

In 1984, developer Will Wright just finished work on his first shoot-em-up video game called Raid on Bungeling Bay . In it, the player controls a helicopter dropping bombs on enemy targets located on a chain of islands. Wright was pleased with his game, which was successful with buyers and critics, but even after its release, he continued to experiment with the relief editor, who used Raid for level design. “It turned out that I was much more interested in doing this part than playing the game itself and bombing targets,” Wright told Onion AV Club. Fascinated by the islands being created, Wright continued to add new features to the level editor, creating complex elements such as cars, people, and homes. He was delighted with the idea of making these islands more like cities, and continued to devise ways to make the world “livelier and more dynamic.”

Trying to figure out how real cities function, Wright found a 1969 book by Jay Forrester called Urban Dynamics . Forrester was an electrical engineer who began his second career in computer simulation; at Urban Dynamicsuses his simulation methodology, which allowed him to propose a theory about the development and withering of cities, which caused conflicting reviews. Wright used Forrester's theories to turn the city level editor from static maps of buildings and roads into living models of a growing metropolis. Over time, Wright became convinced that the “experimental city” was an exciting video game without a logical end. After being released in 1989, the game became insanely popular, sold millions of copies, won dozens of awards, created a whole franchise of followers and dozens of copycats. It was called SimCity .

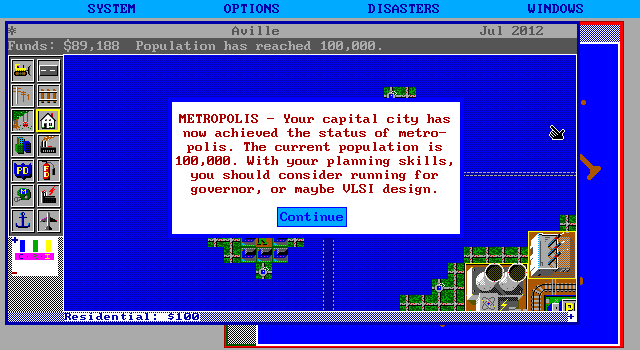

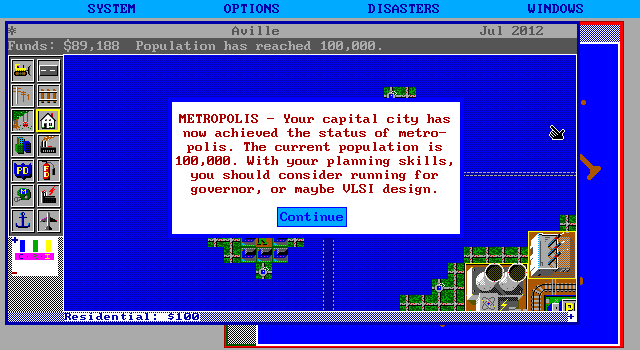

Almost immediately after the release of SimCityJournalists, scholars, and other critics began to discuss the impact that the game can have on planning and politics in the real world. A few years after the game was released, university professors across the country began integrating SimCity into their urban planning and political science courses. Commentators such as the sociologist Paul Starr were worried that the game’s internal code was an “incomprehensible black box” that could “entice” players into accepting its assumptions, such as the fact that low taxes stimulated fertility in the virtual world. “By playing this game, I became a real Republican,” one of SimCity fans told the Los Angeles Times in 1992. "The only thing I wanted was for my city to grow, and grow, and grow."

Despite all the attention, only a few of the writers studied the work that sparked interest in the simulation of cities in Wright. The almost forgotten book of Urban Dynamics by Jay Forrester today claimed that the vast majority of urban strategies in the United States were not only erroneous, but also exacerbated the very problems that they had to solve. Forrester said that instead of development programs in the style of the "Great Society"cities to solve the problems of poverty and withering should use approaches that are less interfering with development, and stimulate rebirth indirectly, through stimulating the business and the class of professionals. Forrester’s message has become popular with conservative and libertarian authors, officials from the Nixon administration, and other critics of the strategy of not interfering in the Great Society’s urban policies. Such views, allegedly supported by computer models, still remain influential among establishment experts and politicians.

Jay Wright Forrester was one of the most important personalities in the history of computer technology, but at the same time one of the most misunderstood. He studied at the Gordon Brought Servomechanics Laboratory at MIT, and during the Second World War he developed automatic stabilizers for US Navy radars. After the war, he led the development of the Whirlwind computer, one of the most important computer projects of the early post-war period. This machine, which initially performed the modest role of a flight simulator, turned into a general-purpose computer that became the heart of the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE), a network of computers and radars worth many billions of dollars, which promised to computerize the response of the U.S. Air Force to a nuclear attack by speeding up the recognition of approaching bombers and automatic withdrawal of fighters for their interception.

In 1956, when the SAGE system was not yet completed, Forrester suddenly decided to change his career, moving from electronic systems to human ones. Suddenly getting a job at the MIT Sloan School of Management, he founded a discipline called “Industrial Dynamics” (later renamed “System Dynamics”). Initially, this area studied the creation of computer simulations of production and distribution problems in industrial firms. But Forrester and his graduate team later expanded it to a common methodology for understanding social, economic, and environmental systems. The most famous example of the work of this group was the Doomsday model of World 3, which became the basis of the work on the ecology of The Limits to Growth , a book warning about the potential collapse of industrial civilization by 2050.

Urban Dynamics was Forrester's first attempt to apply his methodology outside of corporate meeting rooms. He came up with the idea of solving urban problems after meeting with John F. Collins, a conservative Democratic politician who was finishing his term as mayor of Boston. Shortly before, Collins got a job at MIT. Listening to Collins' stories about the mayor’s work in the 1960s, Forrester became convinced that industrial dynamics could be used to study poverty and the outflow of capital associated with the ongoing “urban crisis” in the United States. Despite the fact that Forrester did not have knowledge about urban studies (and about the social sciences in general), Collins agreed that their cooperation could prove fruitful.

Throughout 1968, Forrester devoted twenty-five hours a week to a joint project with Collins. During this time, he met with the former mayor and his team of advisers, and also developed an extensive block diagram of the links between various aspects of the city structure. Forrester translated this flowchart into the DYNAMO simulation language developed by his group. After the secretary or graduate student punched the DYNAMO equations in punch cards, they could be loaded into the machine. Then the computer could generate a working version of the model, and output linear graphs and tabular data describing the evolution of the simulated year, decade after decade.

Forrester spent months experimenting with this model, testing it and checking for errors. He conducted "a hundred or more experiments to study the influence of various strategies on the revival of a city that has entered the stage of economic decline." Six months after the start of the project and 2,000 pages of teletype printouts, Forrester said he reduced the city’s problems to a series of 150 equations and 200 parameters.

At the beginning of the standard 250-year run of the Forrester model, the simulated city is empty. The land is not occupied, there is no economic activity, there are almost no incentives for construction. In the process of gradual development of the city, an increase in its residential sector, population and industry support each other, and the city moves to the stage of stable economic and population growth. During this period, people are drawn to the city, housing estates and enterprises are quickly being built.

But when a city grows up and its land area reaches full employment, growth slows down. The areas considered “attractive and useful” are already occupied. New construction is taking place on more marginal land, and since this area is less attractive, the pace of construction is slowing down. When there is no more free virgin land left for development, new construction becomes impossible, and new housing and production can be built only after the destruction of the old. New migrants, once a boon to the city’s industry, continue to arrive in the metropolis, causing overpopulation and unemployment, weakening economic viability and pushing the city into a deadly spiral of decay and decay.

The plot of this story reflected simplified, and sometimes completely fictitious assumptions in the Forrester model. At the most basic level, Urban Dynamics modeled the relationship between population, housing and industrial buildings, with the influence of government strategies. The city inside the Forrester model was very abstract. There were no neighborhoods, no parks, no roads, no suburbs, no racial or ethnic conflicts. (In fact, the people inside the model did not belong to racial, ethnic, or gender categories at all.) The economic and political life of the outside world did not affect the simulated city. The world outside the model served only as a source of migrants to the city, and a place where they fled when the city became inhospitable.

Residents of the simulated city of Forrester belonged to one of three categories of classes: “professionals and managers”, “workers” and “unemployed”. When someone in the model of urban dynamics was going down the class ladder, classifiers' beliefs about the urban poor came into play: fertility was rising, tax collection was declining, social spending was on the rise. This meant that the urban poor served as a strong brake on the health of the simulated city: it did not contribute to economic life, had large families that increased social spending, and their only investment was miserable crumbs of revenues to the city's treasury.

With caution, Forrester drew conclusions about the correspondence of the model of real life. He warned that his model was an “analysis method,” and that it would not be wise to consider his conclusions applicable, without first making sure that the model's assumptions were appropriate for the situation of a particular city. At the same time, Forrester used the simulation as an analogy to the cities as a whole, making sweeping statements about the failure of what he considered “counterproductive” urban strategies.

According to Forrester, low-income housing was the most obvious example of a “counterproductive” urban development program. In accordance with the model, these programs increased the local tax burden, attracted unemployed people to the city and occupied plots of land that could be used more sensibly for the economy. Forrester warned that housing programs aimed at improving the conditions of the unemployed “increased unemployment and reduced the mobility of economic growth,” condemning the unemployed to lifelong poverty. This idea did not seem to be something new for people who were steeped in the tradition of conservatism or libertarianism, but Forrester’s technical approach to it helped ensure its relevance in the digital age.

When we consider the social influence of computers in political and social life, we usually perceive it in terms of increasing efficiency and new opportunities. The promise of computerization overcomes our critical views on technology. But we also need to be careful how the power of computers and the accompanying language of “systems” and “complexity” can narrow the concept of the politically possible.

Forrester believed that the main problem of urban planning, and of social policy in general, is that "the human brain is not adapted to the interpretation of how social systems behave." The article, which was published in two issues of the libertarian magazine Reason, founded in 1968Forrester stated that in most of human history, it was enough for people to understand causation, but our social systems are driven by complex processes that take place over a long period of time. He believed that our “mental models”, cognitive maps on which consciousness captures the world, poorly help us navigate the network of relationships that make up the structure of our society.

In his view, this complexity meant that political intervention could, and would usually, have social impacts that were very different from those anticipated by politicians. He made a bold statement that "intuitive solutions to the problems of complex social systems" are "almost always wrong." In fact, everything that we do, trying to improve society, has negative consequences and worsens the situation.

In this regard, Forrester’s attitude to the problems of American cities was in line with the “non-interference policy” of Nixon’s influential adviser Daniel Patrick Moynihan and the rest of the presidential administration. Moynihan was an active advocate of Forrester's work and recommended Urban Dynamics to his White House colleagues. Forrester’s arguments allowed the Nixon administration to say that its plans to cut back on programs designed to help the urban poor and people of color would actually help those people.

Forrester’s fundamental statement about system complexity was not new; it had a long history at the right wing of politicians. In the 1991 book Rhetoric of ReactionAlbert O. Hirschman, a specialist in development economics and a historian of economics, called this argument an example of what he called the “vicious argument”. A similar attack, which, according to Hirschman, was used in the writings of Edmund Burke on the French Revolution, he considers a kind of concern trolling (trolling, in which a person seems to defend one point of view, but actually criticizes it). With the help of this rhetorical tactic, a conservative representative can claim that he agrees with your social goal, but at the same time object that the means you use to achieve it will only worsen the situation. When commentators say that “no-platforming only creates more Nazis” (no-platforming - refusing to provide an opportunity to express one’s point of view),

Forrester gave the argument about the perversity of the patina of scientific and computational respectability. Hirschman himself refers to Urban Dynamics and states that the “complex, pseudo-vestment” of Forrester’s models helped to reintroduce this argument into a “decent society.” Almost fifty years after the advent of the “counter-intuitive” style of Forrester’s thinking, he became a generally accepted method of analysis for specialists. For many, “counterintuitiveness” has become a new intuition.

Of course, expert opinion has an important role in a democratic discussion, but it can also drive people out of the process of developing strategies, drown out the importance of moral claims, and program public discourse on a feeling of helplessness. References to the “complexity” of social systems and the possibility of “perverse results” may be enough to destroy transformative social programs that are still at the development stage. In the context of virtual environments such as Urban Dynamics or SimCity, it may not be important, but for decades we have seen evidence in the real world demonstrating the devastating results of claims of “counterintuitiveness” against social security. Direct solutions to the problems of poverty and economic growth - the redistribution and provision of public services - have both empirical justification and moral strength. Perhaps the time has come to listen to your intuition again.

In 1984, developer Will Wright just finished work on his first shoot-em-up video game called Raid on Bungeling Bay . In it, the player controls a helicopter dropping bombs on enemy targets located on a chain of islands. Wright was pleased with his game, which was successful with buyers and critics, but even after its release, he continued to experiment with the relief editor, who used Raid for level design. “It turned out that I was much more interested in doing this part than playing the game itself and bombing targets,” Wright told Onion AV Club. Fascinated by the islands being created, Wright continued to add new features to the level editor, creating complex elements such as cars, people, and homes. He was delighted with the idea of making these islands more like cities, and continued to devise ways to make the world “livelier and more dynamic.”

Trying to figure out how real cities function, Wright found a 1969 book by Jay Forrester called Urban Dynamics . Forrester was an electrical engineer who began his second career in computer simulation; at Urban Dynamicsuses his simulation methodology, which allowed him to propose a theory about the development and withering of cities, which caused conflicting reviews. Wright used Forrester's theories to turn the city level editor from static maps of buildings and roads into living models of a growing metropolis. Over time, Wright became convinced that the “experimental city” was an exciting video game without a logical end. After being released in 1989, the game became insanely popular, sold millions of copies, won dozens of awards, created a whole franchise of followers and dozens of copycats. It was called SimCity .

Almost immediately after the release of SimCityJournalists, scholars, and other critics began to discuss the impact that the game can have on planning and politics in the real world. A few years after the game was released, university professors across the country began integrating SimCity into their urban planning and political science courses. Commentators such as the sociologist Paul Starr were worried that the game’s internal code was an “incomprehensible black box” that could “entice” players into accepting its assumptions, such as the fact that low taxes stimulated fertility in the virtual world. “By playing this game, I became a real Republican,” one of SimCity fans told the Los Angeles Times in 1992. "The only thing I wanted was for my city to grow, and grow, and grow."

Despite all the attention, only a few of the writers studied the work that sparked interest in the simulation of cities in Wright. The almost forgotten book of Urban Dynamics by Jay Forrester today claimed that the vast majority of urban strategies in the United States were not only erroneous, but also exacerbated the very problems that they had to solve. Forrester said that instead of development programs in the style of the "Great Society"cities to solve the problems of poverty and withering should use approaches that are less interfering with development, and stimulate rebirth indirectly, through stimulating the business and the class of professionals. Forrester’s message has become popular with conservative and libertarian authors, officials from the Nixon administration, and other critics of the strategy of not interfering in the Great Society’s urban policies. Such views, allegedly supported by computer models, still remain influential among establishment experts and politicians.

150 equations, 200 parameters

Jay Wright Forrester was one of the most important personalities in the history of computer technology, but at the same time one of the most misunderstood. He studied at the Gordon Brought Servomechanics Laboratory at MIT, and during the Second World War he developed automatic stabilizers for US Navy radars. After the war, he led the development of the Whirlwind computer, one of the most important computer projects of the early post-war period. This machine, which initially performed the modest role of a flight simulator, turned into a general-purpose computer that became the heart of the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE), a network of computers and radars worth many billions of dollars, which promised to computerize the response of the U.S. Air Force to a nuclear attack by speeding up the recognition of approaching bombers and automatic withdrawal of fighters for their interception.

In 1956, when the SAGE system was not yet completed, Forrester suddenly decided to change his career, moving from electronic systems to human ones. Suddenly getting a job at the MIT Sloan School of Management, he founded a discipline called “Industrial Dynamics” (later renamed “System Dynamics”). Initially, this area studied the creation of computer simulations of production and distribution problems in industrial firms. But Forrester and his graduate team later expanded it to a common methodology for understanding social, economic, and environmental systems. The most famous example of the work of this group was the Doomsday model of World 3, which became the basis of the work on the ecology of The Limits to Growth , a book warning about the potential collapse of industrial civilization by 2050.

Urban Dynamics was Forrester's first attempt to apply his methodology outside of corporate meeting rooms. He came up with the idea of solving urban problems after meeting with John F. Collins, a conservative Democratic politician who was finishing his term as mayor of Boston. Shortly before, Collins got a job at MIT. Listening to Collins' stories about the mayor’s work in the 1960s, Forrester became convinced that industrial dynamics could be used to study poverty and the outflow of capital associated with the ongoing “urban crisis” in the United States. Despite the fact that Forrester did not have knowledge about urban studies (and about the social sciences in general), Collins agreed that their cooperation could prove fruitful.

Throughout 1968, Forrester devoted twenty-five hours a week to a joint project with Collins. During this time, he met with the former mayor and his team of advisers, and also developed an extensive block diagram of the links between various aspects of the city structure. Forrester translated this flowchart into the DYNAMO simulation language developed by his group. After the secretary or graduate student punched the DYNAMO equations in punch cards, they could be loaded into the machine. Then the computer could generate a working version of the model, and output linear graphs and tabular data describing the evolution of the simulated year, decade after decade.

Forrester spent months experimenting with this model, testing it and checking for errors. He conducted "a hundred or more experiments to study the influence of various strategies on the revival of a city that has entered the stage of economic decline." Six months after the start of the project and 2,000 pages of teletype printouts, Forrester said he reduced the city’s problems to a series of 150 equations and 200 parameters.

Spirals of death

At the beginning of the standard 250-year run of the Forrester model, the simulated city is empty. The land is not occupied, there is no economic activity, there are almost no incentives for construction. In the process of gradual development of the city, an increase in its residential sector, population and industry support each other, and the city moves to the stage of stable economic and population growth. During this period, people are drawn to the city, housing estates and enterprises are quickly being built.

But when a city grows up and its land area reaches full employment, growth slows down. The areas considered “attractive and useful” are already occupied. New construction is taking place on more marginal land, and since this area is less attractive, the pace of construction is slowing down. When there is no more free virgin land left for development, new construction becomes impossible, and new housing and production can be built only after the destruction of the old. New migrants, once a boon to the city’s industry, continue to arrive in the metropolis, causing overpopulation and unemployment, weakening economic viability and pushing the city into a deadly spiral of decay and decay.

The plot of this story reflected simplified, and sometimes completely fictitious assumptions in the Forrester model. At the most basic level, Urban Dynamics modeled the relationship between population, housing and industrial buildings, with the influence of government strategies. The city inside the Forrester model was very abstract. There were no neighborhoods, no parks, no roads, no suburbs, no racial or ethnic conflicts. (In fact, the people inside the model did not belong to racial, ethnic, or gender categories at all.) The economic and political life of the outside world did not affect the simulated city. The world outside the model served only as a source of migrants to the city, and a place where they fled when the city became inhospitable.

Residents of the simulated city of Forrester belonged to one of three categories of classes: “professionals and managers”, “workers” and “unemployed”. When someone in the model of urban dynamics was going down the class ladder, classifiers' beliefs about the urban poor came into play: fertility was rising, tax collection was declining, social spending was on the rise. This meant that the urban poor served as a strong brake on the health of the simulated city: it did not contribute to economic life, had large families that increased social spending, and their only investment was miserable crumbs of revenues to the city's treasury.

With caution, Forrester drew conclusions about the correspondence of the model of real life. He warned that his model was an “analysis method,” and that it would not be wise to consider his conclusions applicable, without first making sure that the model's assumptions were appropriate for the situation of a particular city. At the same time, Forrester used the simulation as an analogy to the cities as a whole, making sweeping statements about the failure of what he considered “counterproductive” urban strategies.

According to Forrester, low-income housing was the most obvious example of a “counterproductive” urban development program. In accordance with the model, these programs increased the local tax burden, attracted unemployed people to the city and occupied plots of land that could be used more sensibly for the economy. Forrester warned that housing programs aimed at improving the conditions of the unemployed “increased unemployment and reduced the mobility of economic growth,” condemning the unemployed to lifelong poverty. This idea did not seem to be something new for people who were steeped in the tradition of conservatism or libertarianism, but Forrester’s technical approach to it helped ensure its relevance in the digital age.

The argument of viciousness

When we consider the social influence of computers in political and social life, we usually perceive it in terms of increasing efficiency and new opportunities. The promise of computerization overcomes our critical views on technology. But we also need to be careful how the power of computers and the accompanying language of “systems” and “complexity” can narrow the concept of the politically possible.

Forrester believed that the main problem of urban planning, and of social policy in general, is that "the human brain is not adapted to the interpretation of how social systems behave." The article, which was published in two issues of the libertarian magazine Reason, founded in 1968Forrester stated that in most of human history, it was enough for people to understand causation, but our social systems are driven by complex processes that take place over a long period of time. He believed that our “mental models”, cognitive maps on which consciousness captures the world, poorly help us navigate the network of relationships that make up the structure of our society.

In his view, this complexity meant that political intervention could, and would usually, have social impacts that were very different from those anticipated by politicians. He made a bold statement that "intuitive solutions to the problems of complex social systems" are "almost always wrong." In fact, everything that we do, trying to improve society, has negative consequences and worsens the situation.

In this regard, Forrester’s attitude to the problems of American cities was in line with the “non-interference policy” of Nixon’s influential adviser Daniel Patrick Moynihan and the rest of the presidential administration. Moynihan was an active advocate of Forrester's work and recommended Urban Dynamics to his White House colleagues. Forrester’s arguments allowed the Nixon administration to say that its plans to cut back on programs designed to help the urban poor and people of color would actually help those people.

Forrester’s fundamental statement about system complexity was not new; it had a long history at the right wing of politicians. In the 1991 book Rhetoric of ReactionAlbert O. Hirschman, a specialist in development economics and a historian of economics, called this argument an example of what he called the “vicious argument”. A similar attack, which, according to Hirschman, was used in the writings of Edmund Burke on the French Revolution, he considers a kind of concern trolling (trolling, in which a person seems to defend one point of view, but actually criticizes it). With the help of this rhetorical tactic, a conservative representative can claim that he agrees with your social goal, but at the same time object that the means you use to achieve it will only worsen the situation. When commentators say that “no-platforming only creates more Nazis” (no-platforming - refusing to provide an opportunity to express one’s point of view),

Forrester gave the argument about the perversity of the patina of scientific and computational respectability. Hirschman himself refers to Urban Dynamics and states that the “complex, pseudo-vestment” of Forrester’s models helped to reintroduce this argument into a “decent society.” Almost fifty years after the advent of the “counter-intuitive” style of Forrester’s thinking, he became a generally accepted method of analysis for specialists. For many, “counterintuitiveness” has become a new intuition.

Of course, expert opinion has an important role in a democratic discussion, but it can also drive people out of the process of developing strategies, drown out the importance of moral claims, and program public discourse on a feeling of helplessness. References to the “complexity” of social systems and the possibility of “perverse results” may be enough to destroy transformative social programs that are still at the development stage. In the context of virtual environments such as Urban Dynamics or SimCity, it may not be important, but for decades we have seen evidence in the real world demonstrating the devastating results of claims of “counterintuitiveness” against social security. Direct solutions to the problems of poverty and economic growth - the redistribution and provision of public services - have both empirical justification and moral strength. Perhaps the time has come to listen to your intuition again.