Amazing Computer: The ENIAC Story

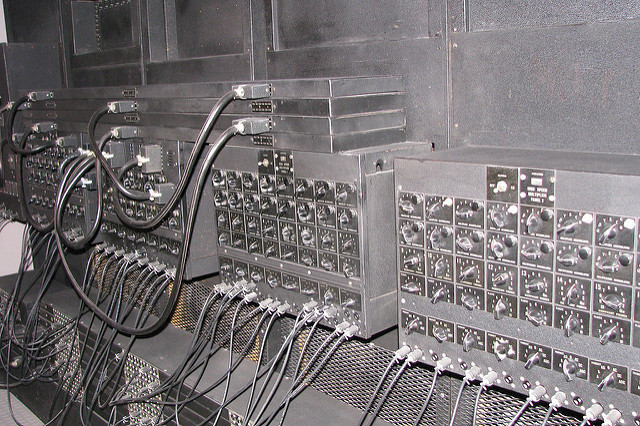

/ photo terren in Virginia CC

We at 1cloud write not only about our development experience , but also talk about technologies related to various aspects of the functioning of cloud services. Today we turn to history and talk about ENIAC.

This amazing computer ushered in an era. The whole history of computer science and computing was divided with its creation on before and after. Let's look at its heyday and what became of this amazing machine after it has served its purpose.

Why ENIAC was needed and where did the word “computer” come from in IT

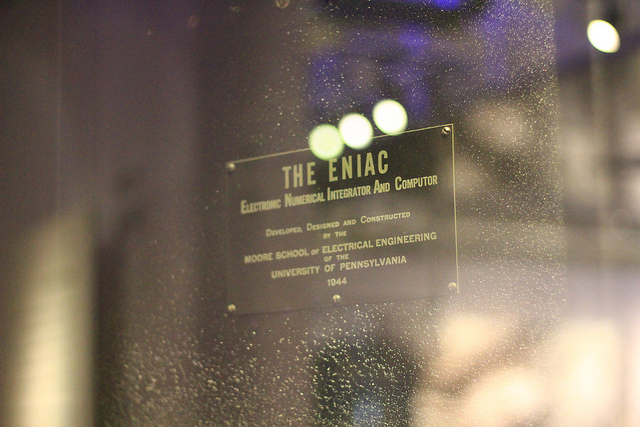

ENIAC, the crown of American engineering in the forties, was created (like many innovations) by order of the military - and this is not surprising, because in the midst of the Second World Army, the United States needed ballistic tables more than ever . These tables were necessary for the gunners for accurate shooting and took into account many indicators that affect the path of the projectile.

By 1943, the Ballistic Research Laboratory, which worked on calculating tables (manually using a “desktop calculator”), barely cope with the increasing volume of calculations. It was then that her representatives turned to the Moore School of Electronics at the University of Pennsylvania with the expectation that scientists would help automate the operation of "computers."

Computers were then called clerks who were involved in calculating tables (ie, "computing"). That is why ENIAC also began to be called a computer - by analogy with hundreds of people who solved the same tasks manually. The Second World War had a great influence on the development of information technology and, in particular, on the creation of ENIAC, despite the fact that the computer itself was only ready for operation in the autumn of 1945. Nevertheless, it was nevertheless used to calculate the tables, although ENIAC played the most significant role in creating a much more formidable weapon than just a projectile that hit the target precisely - calculations were performed on it when simulating a thermonuclear explosion.

Technology before ENIAC

At the time of ENIAC, most of the calculations, both for domestic and scientific purposes, were still carried out “manually”, that is, without using any “smart” technology. A person with paper and a pencil can add two numbers of 10 digits in about 10 seconds. With a pocket calculator - in 4 seconds. Harvard Mark 1 was the last electromechanical computer and could add up two ten-digit numbers in 0.3 seconds, ten times faster than a person.

In an interview recorded by his close friend’s son in 1989 (and published only in 2006), John Presper Eckert, one of those who made the most significant contribution to the creation of ENIAC, recalls that during his studies at Moore’s Electrical Engineering School, two “analyzers” - copies of the Vanitar Bush machine from MIT.

These analyzers could solve linear differential equations - but nothing more. At the same time, the Bush analyzer remained a mechanical device. Eckert wanted to create an electronic computer, so his first idea was to improve the Bush analyzer:

We added [...] more than 400 electronic tubes, which, like everything related to electronics, was not easy to do. [...] Subsequently, I wanted to check whether it is possible to make the entire computing process “electronic”. I talked about this with John Mockley.

As a result, ENIAC appeared - the first electronic digital computer that could add the same two ten-digit numbers in 0.0002 seconds - 50,000 times faster than a person, 20,000 times faster than a calculator and 1,500 times faster than Mark 1. And for specialized scientific computing, he was even faster. At the same time, the scientists had neither an unlimited supply of time, nor the right to make a mistake:

The whole point is that we made a car that did not fail immediately. If the project did not achieve results, developments in this area would slow down for a long time. Usually people build prototypes, see their mistakes and start work anew. We couldn’t do that. We had to make a machine that would work the first time.

/ photo Marcin Wichary CC

John Presper Eckert - One of ENIAC's “Parents”

By the time he began work on the first fully electronic computer, suitable for practical use, John Presper Eckert was only 24 years old. By the way, on the project he was among the leading engineers and one of the few who worked on ENIAC full time. Eckert said that in total about 50 people worked on ENIAC, including 12 engineers and technical representatives. John William Mokley, another famous ENIAC “co-founder”, combined this work with other projects.

We are used to thinking that at age 24, most young people just graduate from university, and by no means get a leading role in the important and urgent project that the military department oversees. Eckert himself said that, despite his rather small age, he was well prepared for this work:

Eckert said that a kind of "school" that helped him begin work on the computer was his passion for electrical engineering. Eckert was born in Philadelphia, during his youth called the Vacuum Tube Valley: it was there that the bulk of the radios and televisions manufactured in the United States were first manufactured. It is not surprising that as a teenager, Eckert worked on a project of a simple TV in the Farnsworth laboratory (he joined the Philadelphia Engineers Club), and, becoming a little older, he dealt with radar problems.

Eckert patented his first development at the age of 21 and subsequently (both before and after ENIAC) worked on dozens of inventions. However, despite all this, he does not believe that without him the creation of a computer would be impossible:

Each inventor does his work based on the results of other scientists. And if it weren’t for me to build ENIAC, someone else would have done it. All that the inventor does is speed up the process.

Myths and Reality

Of course, at the dawn of the fifties, no one could even imagine that modern computers would fit literally in the palm of your hand. Eckert recalls: John Mokley believed that the world would need no more than six computers. This is not surprising - in working order, ENIAC occupied an area of about 1800 square feet [approx. 167 sq.m.] and weighed 27 tons.

ENIAC had just under 18,000 electronic tubes. According to Eckert, the project had at its disposal all the lamps that suppliers could provide. The developers used 10 types of lamps, “although four types would have been enough [technically]” - simply their total number was not enough.

This was done in the hope of thereby reducing the likelihood of damage. Theoretically, ENIAC had a huge number of failure points (1.8 billion failure options per second), which made the idea of using a computer practical for many seemed incredible. Nevertheless, ENIAC broke not so often - only once every 20 hours.

Due to the fact that the machine used just a huge number of lamps (and was an unprecedented invention at that time), various myths and rumors constantly circulated around ENIAC. For example, the story that the working ENIAC cut down the light in all of Philadelphia is popular - Eckert denied it in an interview. They also say that someone had to run around the car with a box of lamps and replace one lamp every few minutes. This is another myth.

Many simply did not believe in the possibility of a fully electronic computer - hence the myth that he could only perform primitive arithmetic operations. However, this would be clearly not enough to drastically speed up the compilation of shooting tables - in fact, ENIAC could solve second-order differential equations. Exactly respectful attitude to the computer is exactly the same fabrication - Eckert categorically denies in his interview the supposedly “fact” that the military saluted the car.

According to John Eckert, the role of John von Neumann in the development of ENIAC is also greatly exaggerated. Nevertheless, amusing cases in the history of ENIAC did occur. For example, Eckert calls the “mouse test” the pure truth:

We knew that the mice would gnaw the insulating layer of wires, so we took all the samples of wires that they could find and put them in a cage with mice to see what insulation they would not eat. We used only those wires that passed the “mouse test”.

/ photo Marcin Wichary CC

What happened after

ENIAC pioneered a whole IT business. In relation to today's computers, it takes about the same place as the Edison bulb - to modern lamps.

Despite its relevance to the military tasks of the beginning of the Cold War and to the development of the entire information technology industry, ENIAC, after the end of its work (the computer would be turned off on October 2, 1955), had an unenviable fate. A computer of historical value has actually rotted in military depots.

40 computer panels, weighing almost 390 kilograms each, after its solemn stop were divided. Part of the panels was in the hands of universities: one was donated to the University of Michigan, and a couple more were acquired by the Smithsonian Institution. However, the rest of the panels were simply sent to the warehouses - the recording system on some of them was not kept carefully enough, the years went by, and the new management, coming to work, no longer suspected that the pile of metal in any hangar was of any value.

The team of billionaire Ross Perot took up the search for what was left of ENIAC when he decided to look for rarities from the world of technology to decorate his office. It turned out that some of the panels had once been transported from a test site in Aberdeen (Maryland) to Fort Sill in Oklahoma to the military museum of field artillery.

The curator of the museum was shocked to learn that the museum had the largest ENIAC block in the world - a total of nine panels, all of which were stored in nameless wooden boxes that had not been opened for many years. Fort Sill officials said they did not know how they had almost a quarter of the ENIAC computer.

Fort Sill agreed to give the Feather of the panel in exchange for a promise that the remnants of ENIAC would be restored at least externally. It immediately became clear to the engineers who got down to business - they won’t be able to bring the computer into operation, if only because all 40 panels would be needed, not to mention all the other components and lost knowledge. Therefore, they faced a simpler task: to do what was left of ENIAC, at least outwardly resembling a landmark computer in its heyday.

The panels were cleaned of dust and rust, treated with a sandblasting apparatus and re-coated with paint, after which the new lamps were neatly soldered to them (for a look, of course). For some time, the updated panels were located in the office of Perot Systems, however, after its merger with Dell, the management decided to return the restored ENIAC blocks to the Fort Sill Museum. Unfortunately, from the former greatness of this computer, only a shell remained - and even that one was not completely preserved.

Ross Perot’s staff compares ENIAC to the Ark of the Covenant from the Indiana Jones movie - it was just as completely lost, despite its importance, because military museums and warehouses did not even suspect what had been stored in their stores for so many years. Nevertheless, several years ago, Dell still talked about trying to find the rest of the ENIAC panels that had not completely collapsed - it remains to be hoped that they still exist.

PS Other materials on how we improve the performance of the virtual infrastructure provider 1cloud :