Flux in pictures

- Transfer

- Tutorial

We at Hakeslet like ReactJS and Flux. It seems to us that this is the right direction of development. We love functional programming and pure functions, and when complex architectures are simplified by the approaches associated with them, it's cool. React already has a lot of resources on the Internet, including our practical course on React JS . The final lesson in this course is called Unidirectional Data Dissemination, and there we come to an interesting topic that underlies the Flux architecture.

Flux is an application data dissemination pattern. Flux and React grew up on Facebook together. Many use them at the same time, but nothing prevents them from being used individually. They were created to solve a specific problem on Facebook.

We use React and Flux in our Hexlet IDE browser development environment (it is open source), in which students complete practical tasks. Flux is simultaneously very popular and very incomprehensible to many in the world of the web. Today's translation is an attempt to explain Flux on the fingers (well, that is, pictures).

First you need to understand what problem Flux solves.

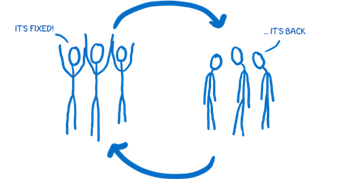

A famous example is a bug with notifications. You go to Facebook, you see a notification at the message icon. Click, but there is no new message. Notification disappears. Then, after a few minutes of interaction with the site, the notification returns. Click again ... and again there are no messages. And so again and again and again.

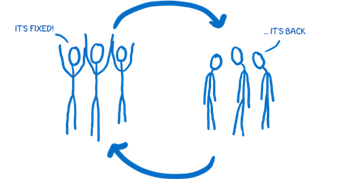

It was not just a cyclical bug for the user. This was a cyclical issue on the Facebook team. They fixed it, and for a while the bug disappeared, but then appeared again and again and again: issue → fixed → issue → fixed ...

They looked for a way to solve the problem once and for all. Not just fix the bug, but make sure that the system does not allow such bugs to appear.

A fundamental problem lay in the mechanism of data movement within applications.

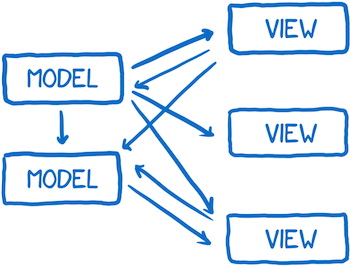

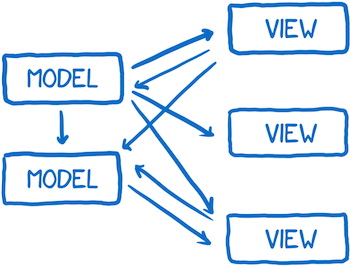

There are models containing data, and they transfer data to a layer that renders the data.

The user interacts with the view, so the view sometimes needs to update the model based on user input. And sometimes models need to update other models.

In addition, actions sometimes generate cascading changes. I imagine all this as an intense game in Pong : it is difficult to understand where the ball will fly (and whether it will fall off the screen at all).

Add to this the possible asynchronous changes. One change can generate several others. It's like throwing a bunch of table tennis balls onto Pong's screen so that they fly in all directions along intersecting paths.

In general, you can debug this stream of data.

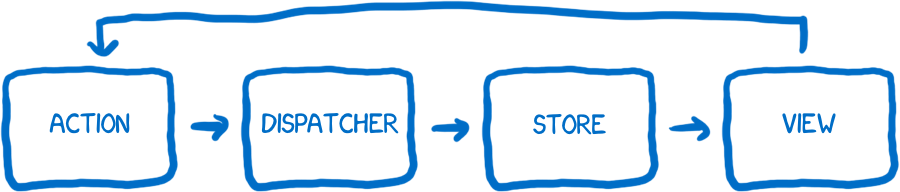

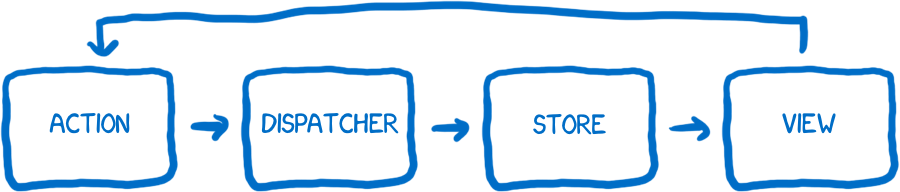

Facebook decided to try a different architecture in which data always moves in one and only one direction. And when you need to add new data, the stream starts from the very beginning. Called this Flux architecture.

This is actually a cool thing ... but the picture above is probably not noticeable.

Once you deal with Flux, the picture will become clearer. The problem is that if you start studying Flux documentation from scratch, this illustration does not help to understand the point. She didn’t help me. But a different approach helped: I began to think of the system as a set of characters who work together to achieve a result. So here, get acquainted, these are my fictional friends.

First, I’ll introduce everyone in a quick way.

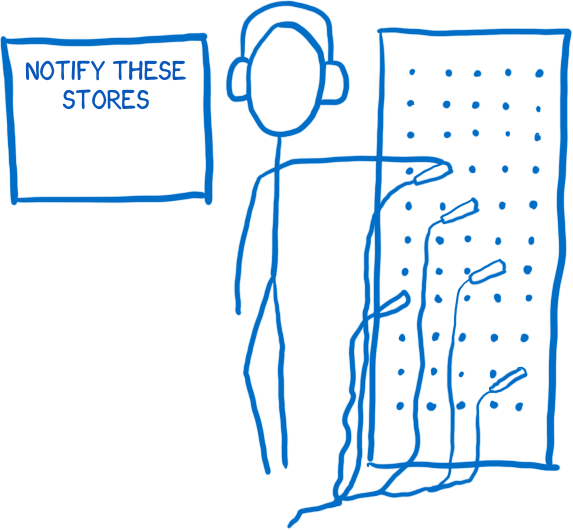

The first character is the creator of the action. It generates actions (actions), and all changes and interactions with the system pass through it. If you want to change the state of the application or want to change the view, you need to create an action.

I present him as a telegraph operator. You know which message to send, and the action creator formats it so that other parts of the system understand.

An action has a type and a load. A type is one of the types specified in the system (usually a list of constants). For example, MESSAGE_CREATE or MESSAGE_READ.

It turns out that part of the system knows about all the possible actions. This fact has a beneficial side effect. A new developer can open the action creator files and see the entire API - all possible state changes in the system.

The created action is transferred to the dispatcher.

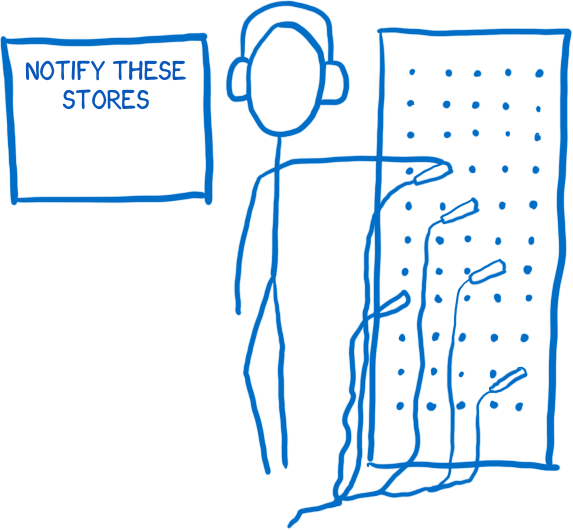

Roughly speaking, the dispatcher is a large register of callback functions (callbacks, callbacks). Something like an operator at a telephone exchange. He has a list of all the repositories to which you need to send messages. When a new action arrives from the action creator, the dispatcher passes it to the desired store.

He does this synchronously, which simplifies the situation with many balls in the Pong game, which I mentioned above. And if you need to specify dependencies between storages (so that one store is updated before the other), you can use waitFor () in the manager.

The Flux dispatcher differs from dispatchers in other architectures. The action is sent to all registered vaults, regardless of the type of action. This means that the repository does not just subscribe to certain actions. It learns about all the actions and filters those that make sense to him.

The repository contains the state of the application, and all the logic of the state change lives inside.

I imagine a storehouse in the form of a meticulous bureaucrat who controls more than necessary. All changes must be made by him personally. And you cannot directly request a state change. The repository has no setters. To request a state change, you need to follow a special procedure ... you needto write a statement addressed to the director to submit an action through the channel of the action creator and dispatcher.

As mentioned above, if the store is registered with the dispatcher, all actions will be sent to it. Inside the repository there is usually a switch that checks the type of action and decides whether or not to respond to it. If the store responds to actions, then it needs to make changes based on it and update the state.

After the change, the store generates a change event. The controller view learns about a state change.

Views are responsible for rendering the state for the user, as well as for receiving input from the user.

Kind is a presenter. He does not know anything in the application, he only knows about the data that was transferred to him, and how to format this data so that people can understand (using HTML).

A controller view is a mid-level manager or agent between a repository and a view. The repository informs him of a state change. He receives a new state and transfers it to all his species.

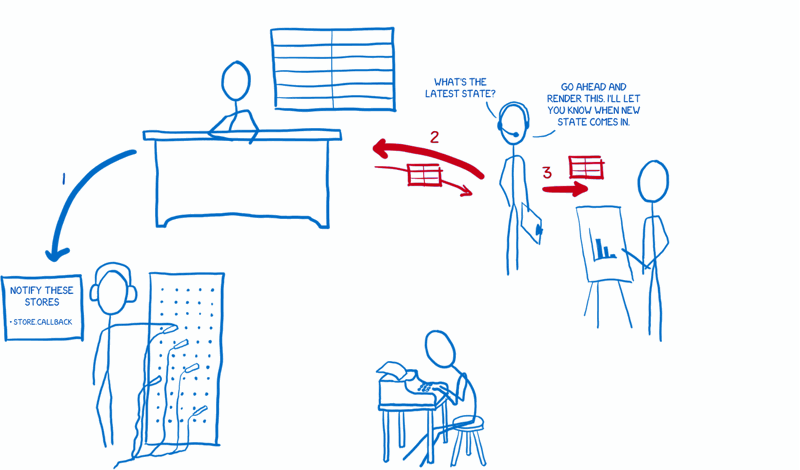

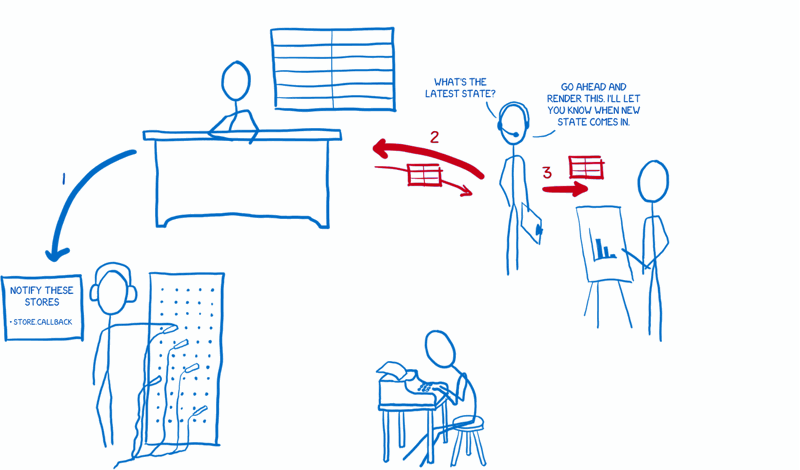

At the beginning - the organization. Application initialization occurs only once.

1. Repositories inform the dispatcher that they want to receive notification of actions.

2. The view controller requests the latest state from storage.

3. When the repositories respond, the controller views pass these states to their child views for rendering.

4. View controllers ask repositories to inform them of state changes.

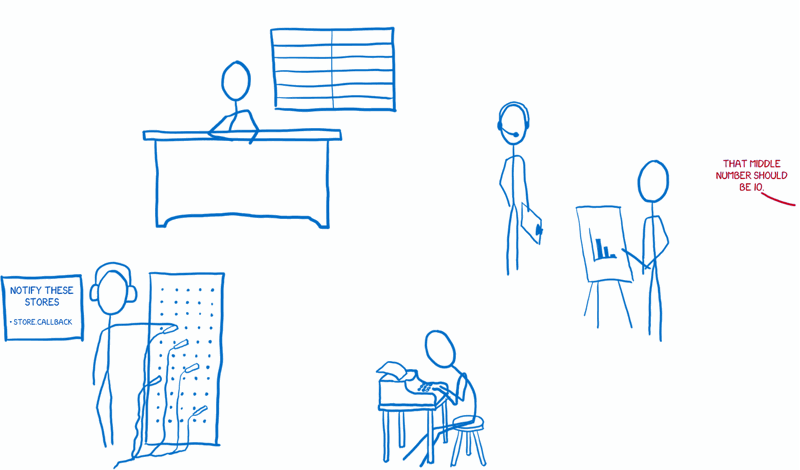

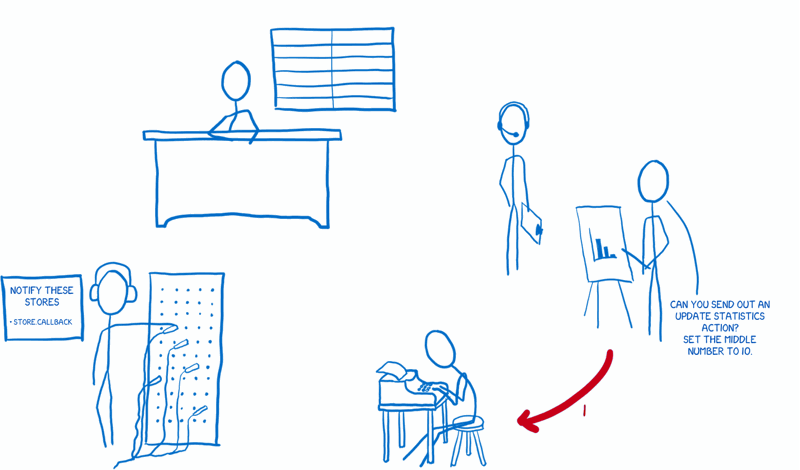

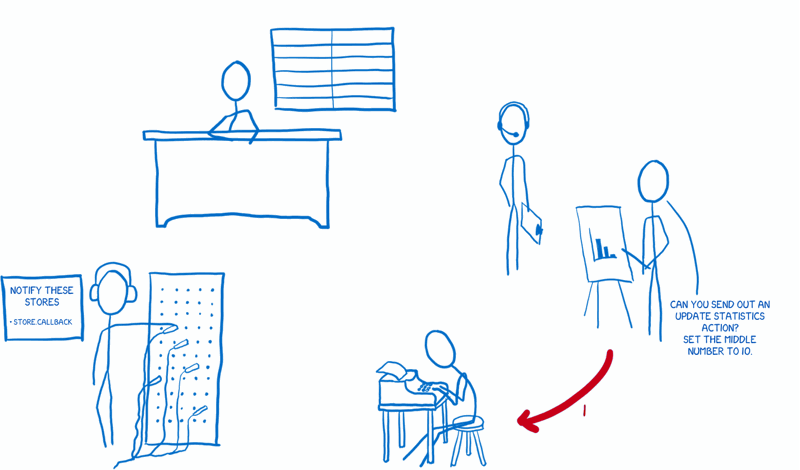

When initialization is complete, the application is ready to accept input from the user. Let's generate the action as if the user made the change.

1. The view tells the creator of the action to prepare the action.

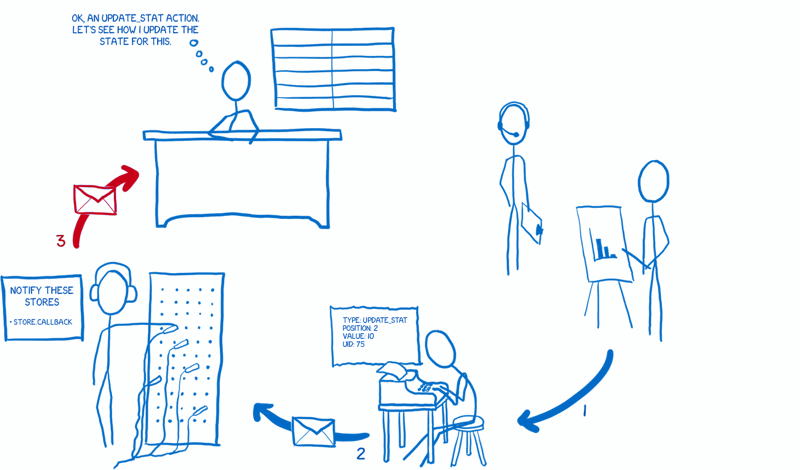

2. The action creator formats the action and sends it to the dispatcher.

3. The dispatcher sends the action to the repositories in order. Each store receives a message about all the actions. Then it decides whether to respond to the action or not, and updates (or does not update) the state accordingly.

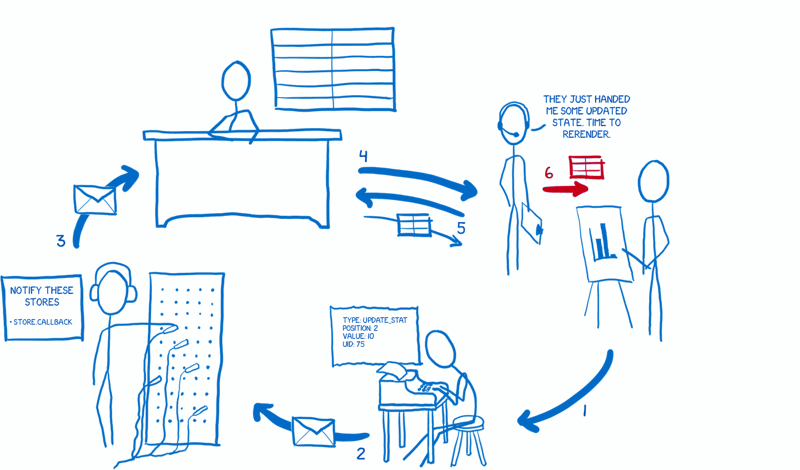

4. After the state changes, the store notifies view controllers that are subscribed to it.

5. These view controllers ask the store to give them an updated state.

6. After the store transfers its state, the view controller will ask its child views to be re-rendered in accordance with the new state.

This is how I imagine Flux's work. Hope this helps you too!

Resources

Flux is an application data dissemination pattern. Flux and React grew up on Facebook together. Many use them at the same time, but nothing prevents them from being used individually. They were created to solve a specific problem on Facebook.

We use React and Flux in our Hexlet IDE browser development environment (it is open source), in which students complete practical tasks. Flux is simultaneously very popular and very incomprehensible to many in the world of the web. Today's translation is an attempt to explain Flux on the fingers (well, that is, pictures).

Problem

First you need to understand what problem Flux solves.

A famous example is a bug with notifications. You go to Facebook, you see a notification at the message icon. Click, but there is no new message. Notification disappears. Then, after a few minutes of interaction with the site, the notification returns. Click again ... and again there are no messages. And so again and again and again.

It was not just a cyclical bug for the user. This was a cyclical issue on the Facebook team. They fixed it, and for a while the bug disappeared, but then appeared again and again and again: issue → fixed → issue → fixed ...

They looked for a way to solve the problem once and for all. Not just fix the bug, but make sure that the system does not allow such bugs to appear.

Fundamental problem

A fundamental problem lay in the mechanism of data movement within applications.

There are models containing data, and they transfer data to a layer that renders the data.

The user interacts with the view, so the view sometimes needs to update the model based on user input. And sometimes models need to update other models.

In addition, actions sometimes generate cascading changes. I imagine all this as an intense game in Pong : it is difficult to understand where the ball will fly (and whether it will fall off the screen at all).

Add to this the possible asynchronous changes. One change can generate several others. It's like throwing a bunch of table tennis balls onto Pong's screen so that they fly in all directions along intersecting paths.

In general, you can debug this stream of data.

Solution: unidirectional data stream

Facebook decided to try a different architecture in which data always moves in one and only one direction. And when you need to add new data, the stream starts from the very beginning. Called this Flux architecture.

This is actually a cool thing ... but the picture above is probably not noticeable.

Once you deal with Flux, the picture will become clearer. The problem is that if you start studying Flux documentation from scratch, this illustration does not help to understand the point. She didn’t help me. But a different approach helped: I began to think of the system as a set of characters who work together to achieve a result. So here, get acquainted, these are my fictional friends.

Get to know

First, I’ll introduce everyone in a quick way.

Creator of an action

The first character is the creator of the action. It generates actions (actions), and all changes and interactions with the system pass through it. If you want to change the state of the application or want to change the view, you need to create an action.

I present him as a telegraph operator. You know which message to send, and the action creator formats it so that other parts of the system understand.

An action has a type and a load. A type is one of the types specified in the system (usually a list of constants). For example, MESSAGE_CREATE or MESSAGE_READ.

It turns out that part of the system knows about all the possible actions. This fact has a beneficial side effect. A new developer can open the action creator files and see the entire API - all possible state changes in the system.

The created action is transferred to the dispatcher.

Dispatcher

Roughly speaking, the dispatcher is a large register of callback functions (callbacks, callbacks). Something like an operator at a telephone exchange. He has a list of all the repositories to which you need to send messages. When a new action arrives from the action creator, the dispatcher passes it to the desired store.

He does this synchronously, which simplifies the situation with many balls in the Pong game, which I mentioned above. And if you need to specify dependencies between storages (so that one store is updated before the other), you can use waitFor () in the manager.

The Flux dispatcher differs from dispatchers in other architectures. The action is sent to all registered vaults, regardless of the type of action. This means that the repository does not just subscribe to certain actions. It learns about all the actions and filters those that make sense to him.

Storage

The repository contains the state of the application, and all the logic of the state change lives inside.

I imagine a storehouse in the form of a meticulous bureaucrat who controls more than necessary. All changes must be made by him personally. And you cannot directly request a state change. The repository has no setters. To request a state change, you need to follow a special procedure ... you need

As mentioned above, if the store is registered with the dispatcher, all actions will be sent to it. Inside the repository there is usually a switch that checks the type of action and decides whether or not to respond to it. If the store responds to actions, then it needs to make changes based on it and update the state.

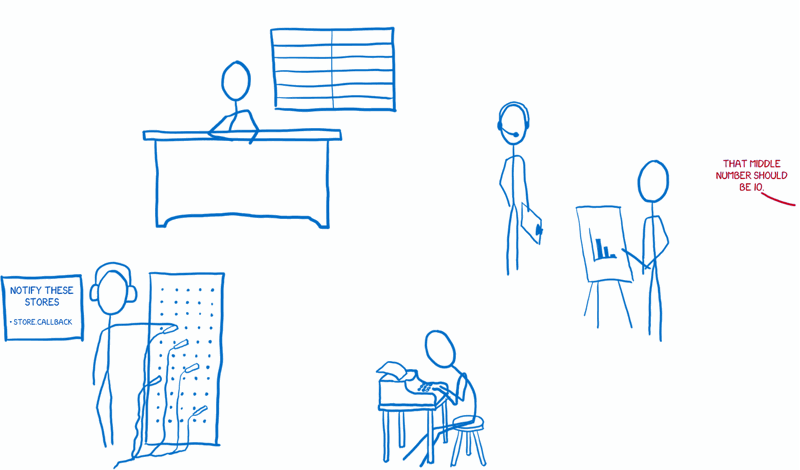

After the change, the store generates a change event. The controller view learns about a state change.

Controller view and view

Views are responsible for rendering the state for the user, as well as for receiving input from the user.

Kind is a presenter. He does not know anything in the application, he only knows about the data that was transferred to him, and how to format this data so that people can understand (using HTML).

A controller view is a mid-level manager or agent between a repository and a view. The repository informs him of a state change. He receives a new state and transfers it to all his species.

How they all work together

Organization

At the beginning - the organization. Application initialization occurs only once.

1. Repositories inform the dispatcher that they want to receive notification of actions.

2. The view controller requests the latest state from storage.

3. When the repositories respond, the controller views pass these states to their child views for rendering.

4. View controllers ask repositories to inform them of state changes.

Data stream

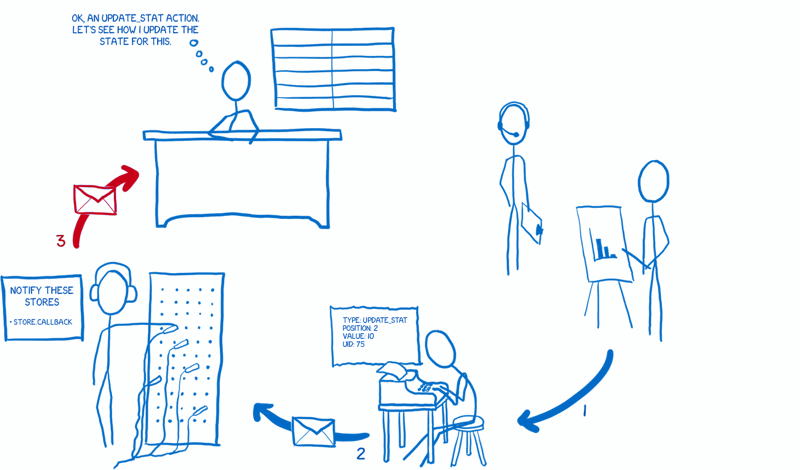

When initialization is complete, the application is ready to accept input from the user. Let's generate the action as if the user made the change.

1. The view tells the creator of the action to prepare the action.

2. The action creator formats the action and sends it to the dispatcher.

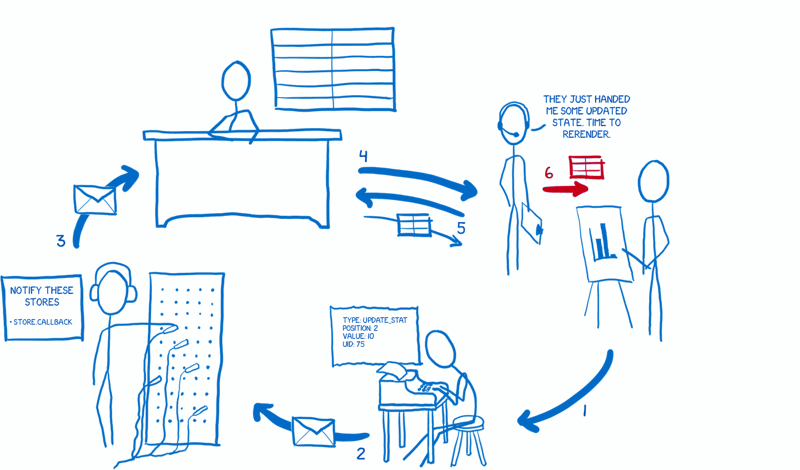

3. The dispatcher sends the action to the repositories in order. Each store receives a message about all the actions. Then it decides whether to respond to the action or not, and updates (or does not update) the state accordingly.

4. After the state changes, the store notifies view controllers that are subscribed to it.

5. These view controllers ask the store to give them an updated state.

6. After the store transfers its state, the view controller will ask its child views to be re-rendered in accordance with the new state.

This is how I imagine Flux's work. Hope this helps you too!

Resources