Warm and lamp: five balalaika about magnetic recording technology

Okay, Habr, in the previous post I (intentionally) paid more attention to the nostalgic rydalka on the topic of audio cassettes than the technical part. In this post I am correcting. Audio tapes are very interesting because the history of this technology can be traced from the beginning (1962) to the end (the end of the nineties - the beginning of the two thousandths). In a more familiar digital universe, we still have few similar examples. Eight-bit computers? No, their principle is still alive today in controllers and other Arduino. CRT monitors are a fertile topic about a warm-tube image, but if you only lift a modest 17-inch device once, you just want to welcome progress with all your arms, legs and back.

Okay, Habr, in the previous post I (intentionally) paid more attention to the nostalgic rydalka on the topic of audio cassettes than the technical part. In this post I am correcting. Audio tapes are very interesting because the history of this technology can be traced from the beginning (1962) to the end (the end of the nineties - the beginning of the two thousandths). In a more familiar digital universe, we still have few similar examples. Eight-bit computers? No, their principle is still alive today in controllers and other Arduino. CRT monitors are a fertile topic about a warm-tube image, but if you only lift a modest 17-inch device once, you just want to welcome progress with all your arms, legs and back.Is that voice modems are a good example of "closed" technology. What makes these technologies interesting is the opportunity to explore all the stages of development. Here is the initial stage, when devices are expensive, and their consumer properties are far from ideal. Here is the golden age: technology is becoming mainstream, considerable funds are invested in R & D, the highest quality of the product is achieved, but only in the most expensive items. Here is the sunset: there is already a fresher technology, prices and margins are falling, products are rapidly becoming simpler, reliability is falling. But the afterlife: produced only penny, the simplest device, the minimum performing the specified function, sadly and not so good.

If you try to draw (possibly unjustified) parallels, now the smartphone market is at the peak of its “power”. The variety is huge, the margin (for some) is decent, there are top models with a wild price tag and optional but pleasant elite bonuses. It is possible that this will not always be the case, but is there a replacement for smartphones? And here's what: I'm not sure that a cheap phone differs from an expensive one so radically as an expensive and cheap tape recorder is different from each other. Let's talk about the difficulties of recording on a magnetic tape or about forty years of attempts to cope with the ineradicable impairment of format.

Balalaika the first: closed path

Even before it is possible to read something from a magnetic tape, it is desirable to ensure that it is pulled as evenly as possible past the magnetic head. In devices that really matter : in tape recorders, DAT digital recorders and modern tape drives, the tape is pulled out of the tape.

The same thing happens in large reel tape recorders. In compact cassettes, such an approach was abandoned, in order to reduce the cost of both the tape recorders and the carriers. Because of this, as well as because of the low (also due to economy) tape speed (4.76 centimeters per second, two or even four times less than the typical speed of reel tape recorders), cassette technology has a relatively high detonation coefficient. This characteristic (in English known as wow and flutter) shows how evenly a tape recorder or record player can rotate a record or pass a tape past a magnetic head. The tape recorder, which turns the tape quickly or slowly, has its own firm and well-recognized sound handwriting - such as with a scream, which is what this feature is called “wow” in English.

Over time, the sound quality cassette, if it didn’t even out, then came as close as possible to that of the “big” tape recorders, due to a lot of tweaks, including in the category of uniform pulling of the tape. In serious cassette decks, for this purpose, separate engines are used, which rotate only the capstan, and the rest of the engines are simpler. And also the closed path is used: this is when there are two deafers in the tape recorder. The tape turns out "clamped" between two rotating metal pins to which rubber rollers are pressed from below, and due to the different diameter of the shafts it is also tensioned between them. This is not an easy construction. In the tape recorder that I bought, there was no drive belt that “held” the left reel of tape. Without him, she spun excessively, and the excess tape was chewed with the first pinch roller. More precisely not quite chewed, and so, gently nibbled. Khm In a conventional tape recorder with one capstan, there would simply be no such problem.

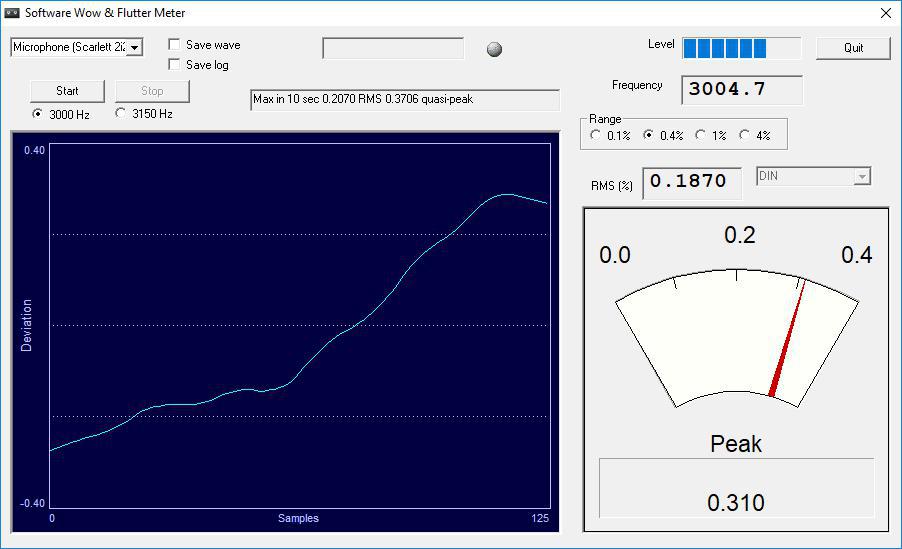

Measuring the detonation coefficient is now possible with the help of a computer and a sound card. The screenshot shows the wfgui program. The measurement is done like this: we record a sinusoidal tone with a frequency of 3000 or 3150 hertz on a tape. We reproduce, and the program counts deviations from the given frequency. The screenshot shows an average deviation of 0.2% - this is five times more than my tape recorder should have, simpler at the level of tape decks. However, after a couple of weeks of operation, the detonation coefficient dropped to a very good 0.05%. This parameter in the tape recorder is affected by almost everything, including the quality of the pressure rollers made of rubber, the uniformity of the engines, the presence of lubricant where the axes of the chargers are fixed. I propose once again to rejoice that in digital technology we have long since got rid of this necessity of “wiping optical axes”.

Oh yeah, if you measure the detonation coefficient as mentioned above, then this will be a combined recording and playback ratio. Ideally, a reference cassette is also needed, where a signal with a given frequency is recorded with minimal detonation. It also comes in handy if you want to calibrate the speed of your tape recorder as accurately as possible, otherwise it can play the cassettes recorded on it as normal, but the others - as lucky. Argh.

Balalaika the second: about the types of magnetic tape

As far as I can remember, this switch of tape types of the type “Normal - Cr0² - (optional) Metal” was on almost all my devices. But I thought it was something useless, because, during the period when the cassettes were relevant, I never had anything but a tape of the first type “Normal”. The cassettes were divided into “Soviet” and “imported”; something was recorded on the “new” and “thirty-three times already”. I just dreamed of a new cassette, at least some, and did not think about varieties.

So this year I tried to record and listen to tape of different types for the first time. There were four types of tape. The first, the most common - is based on iron oxide, or, popularly speaking, rust. The tape of the second type uses chromium oxide or similar compounds. In the tape of the third type - a combination of iron oxide and chromium, but for several reasons it did not take root. Finally, pure metal is used in the fourth type of tape.

If you do not go into much technical details, you can record a more powerful signal on the Type II and Type IV tapes, thereby increasing the signal-to-noise ratio. So, a better tape less hisses. But it is also capable of transmitting the audible frequency range more accurately. Therefore, this characteristic in the technical properties of the tape recorder is always indicated depending on the type of tape. When playing for tapes of the first type and for the second and fourth, different parameters of signal equalization are used, therefore in cheap players there is a switch, and in expensive decks there is an automatic determinant of the tape type using holes on the tape end.

From bottom to top - Mongol Shuudan, a tape cassette of the first type, second and fourth.

With a normal (first type) tape, a brand tape hiss will be heard almost always, and you can get rid of it only with the help of noise reduction systems (a separate balalaika is described below). The tape of the second type is noticeably noisy only in the quietest musical moments, and in pauses, and then if you unscrew the volume to the maximum. In a normal situation, if the noise is heard, it is almost not annoying. I did not notice the difference between the tapes of the second and fourth types neither by ear nor by measurements. Maybe I caught not the best sample of "metal" tape.

The tape of the first type is still sold in retail. Cassettes can not be bought at the gas station, but with delivery - easily (and in a more conservative America, you can buy a regular grocery store). They will cost 150-200 rubles apiece, it is not very expensive, but also expensive. Tapes of the second and fourth types are not produced, and all that is on sale is sealed copies preserved from “those times”. The sect of witnesses shhhh argues that even forty years old copies are written and heard perfectly, and most likely it is. But the prices ...

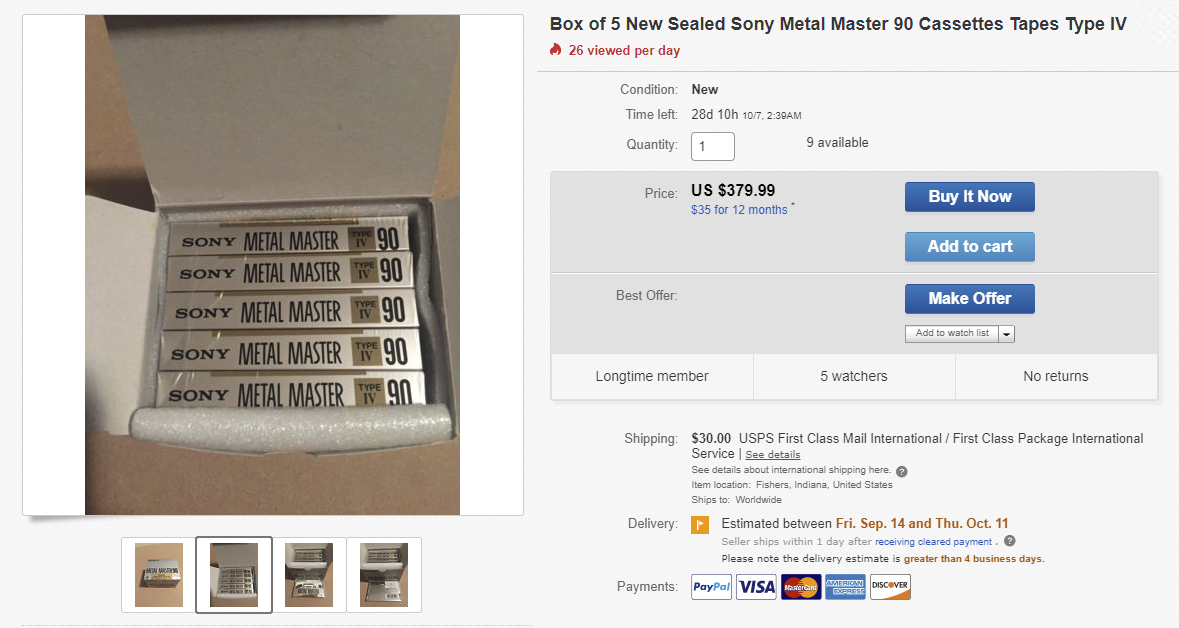

Well, in the screenshot above, an extreme example: Sony's over-piped tape in a ceramic (!) Package. Cartridges of the second type can be bought from 400 rubles for the two-thousandth version, and from 1000 rubles for a copy of more vintage times, when (as old-timers recall) the quality of tapes, cases, and other spare parts was better. The prices of metal tapes are simply irresponsible, from $ 20 to $ 100 per piece.

Obviously, it was precisely the sealed cassettes that became a collection item, like brands: there the value is no longer possible to write something down on them. Value in a rarity of a series, prescription of production, eliteness of registration. I was lucky, and I came across a cheap batch of tapes that were once recorded, and since then nobody touched them - this can be understood by the ideal state of plastic boxes. The tape TDK SA90 of the second type is such an optimal variant of recording on the tape, from which it will not be a shame even in the digital year 2018. You can read more about chrome ribbons in this vintage BASF brochure .

Balalaika the third: what happens to rubber in a quarter century

Rubber becomes almost liquid. A typical description of the lot on eBay from the original owner: "listened, then stopped, recently got it, but it buzzes, but does not work." If you know what to do with such a device, you can buy a very high-quality tape recorder quite inexpensively.

The photo shows a rubber drive for the Sony TC-K511S tape recorder released in 1993. For 25 years, the material of the belt was softened, but it did not completely lose its shape, and it turned out just to be removed. In a Kenwood tape recorder, released just two years earlier, the remnants of the belt pollute the mechanism, and in some unfortunate cases, they can disable the tape recorder completely. Anyway serious cleaning will be required. A similar situation is observed in portable players, in short, wherever rubber is used. Prophylactic belt replacement seems to be required for all cassette recorders, with the exception of those using direct drive. And that, minor units there probably use rubber belts.

In an amicable way, it is impossible to limit passic. Ideally, you need to change the rubber pressure rollers, which together with the metal pins of the impaler, the uniform movement of the tape. They are usually either heavily polluted, or the rubber has also lost its properties, cracks have appeared. But often quite thoroughly (more than once and not twice) clean them with a cotton swab with pure alcohol. The rest of the moving parts of the tape recorder are more durable, although also as lucky. In cheap devices, where everything is plastic, gears can crack (in particularly unfortunate cases, plastic also begins to “spread”). Magnetic heads themselves are wiped. The lubricant dries, making it difficult for the mechanism to work. Motors lose their properties - and music plays slower or faster than necessary. Capacitors flow. Stretched or burst spring mechanical buttons. Light bulb burns out

If you ask me what can go wrong in the old tape recorder, I will answer: almost everything! And everywhere in different ways: in a cheap tape recorder of the end of the 90s the construction will be guilty of failures, in expensive decks of the end of the 80s - its complexity. Perhaps an iron monster from the 70s with a minimum of electronics will outlast them all. In theory, modern devices - smartphones, laptops, portable players - should be much more durable, they often have no moving parts at all. But it is in theory. First, the consumer culture is different now; few people buy an expensive laptop to use it for 10-15 years. Secondly, we still do not know which of the current models are successful and which are not. Of the laptops 20 years ago, there are many models that seem to have not survived to our time. And there are those that look and work like new.

Another story about the repair of a portable player is in my Telegram channel .

Balalaika the fourth: about the bias current (caution, dragons!)

The bias current or BIAS is more difficult to describe in human words. I will try, but a little later, but first I will write inhuman , ahahaha. Information and pictures taken from this brochure .

How do you record on tape? The tape is pulled past the magnetic head. The electromagnet comes into direct contact with the ribbon and imprints on it a “pattern” of metal particles magnetized with a specific polarity. The reading head transforms changes in magnetic polarity into changes in the polarity of the electrical signal, and, accordingly, into sound. Everything is very simple, but not quite. Coercive force comes to the scene: such a property of ferromagnetics (to which the magnetic tape also applies) that they cannot simply be demagnetized or reversed the polarity of the magnetization.

The problem is that in order to remove a ferromagnet from a stable state — for example, to change the polarity — a serious impact is required. In the electrical system, a change in polarity occurs instantly (in the picture on the left), in a magnetic tape — it takes some time (in the center), and for sound this means introducing obvious distortions (on the right). What to do? If, together with the useful signal, we act on the tape with another high-power signal and a very high frequency, there will be less distortion in the useful signal. It is this additional signal called bias current. This is a sinusoidal signal of very high frequency, beyond the capabilities of human hearing (from 75 kilohertz, and in my tape recorder it is 210 kHz).

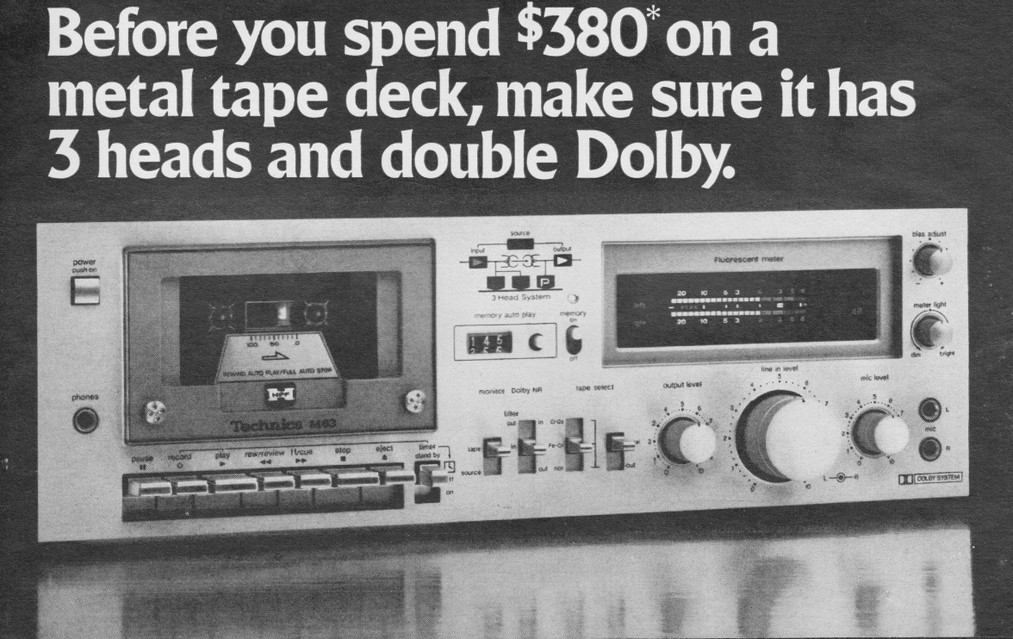

No, you understand what is happening? A literature teacher enters the classroom and, although he does not interact with the students at all, the essay begins to be written a little better! The power of the bias current depends on the type of tape: that is why Normal Bias is written on the first type of cassettes, and High on the second type (they have different coercive force). The bias current can also be adjusted to achieve optimal sound, but you have to choose - either less distortion or a wider frequency range. On expensive tapes, this inevitable (one of many) compromise is not so pronounced. High-end cassette recorders can calibrate bias current for a specific tape, manually or automatically: high and low frequency signals are recorded on the tape, immediately read by a separate playback head,

Balalaika Fifth: Noise Reduction Systems

We have already discussed mechanical and, so to speak, research methods of improving the quality of recording onto a tape. Let's discuss how you can change the sound signal during recording so that there is less noise and more music when playing. This is the responsibility of noise reduction systems historically developed by Dolby (but not only). Three different versions of Dolby noise reduction systems got into the equipment for end users. At first it was Dolby B - it was introduced in 1968, and almost all music tapes were recorded using it.

In 1980, the Dolby C system appeared. It was necessary to add a switch between different noise reduction systems to tape recorders. In 1989, already at the decline of the cassette theme in Western countries, the Dolby S system appeared. How do they all work? Consider the example of Dolby B.

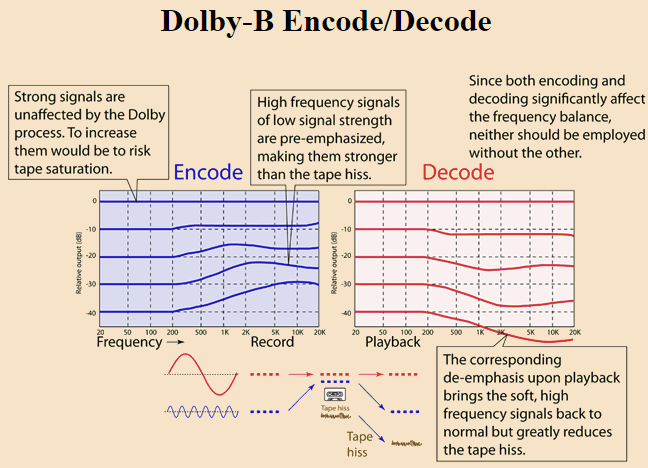

The picture is taken from here , and there are still a lot of interesting things. At the same time, you can evaluate how the typical home page looked in the mid-90s. The idea is simple: let's record more tapes on the tape so that less noise is heard. Since the hiss of the cassette most often affects the high frequencies, they can be amplified during recording, and during playback, the signal level can be restored. Profit?

Not really: you can not infinitely enhance the signal level, otherwise the level of distortion will immediately become beyond. The Dolby system selectively amplifies the high-frequency component of the sound of a relatively low volume, that is, it works in quiet places, where it is necessary, and in loud ones it tries not to interfere, and everything is fine there. Alas, this solution has certain disadvantages. First, to increase and decrease the level of the signal should be symmetrical. It does not always work. And the cassette is not an ideal medium; the distortions it introduces can confuse the noise reduction system. And the implementation of the system may differ on tape recorders from different manufacturers.

Dolby C applies a similar approach to both high and low frequencies. Dolby S is an even more complex multi-band signal processing system that promises noise reduction up to 10 dB in the low-frequency range and up to 24 dB in the high-frequency one. Here in this wonderful video of the channel Techmoan about cassettes and modernity it is shown how three different Dolby systems struggle with pure noise when there is no useful signal, that is, noise reduction works in ideal conditions.

I experienced all three noise reduction systems. You can evaluate the effect of Dolby B and Dolby C on my video from the previous post.. I tried the Dolby S on a relatively simple Sony tape recorder, and with this noise system, the tapes really can't be heard. The problem is that all three systems are a little bit, but they change the music signal, and not at all the way I would like. It's 2018 in the yard, and I have no problem listening to music without hissing! If in 1989 Dolby S was presented as a way to write sound on a tape with a quality almost like a CD, now cassettes are interesting just because their sound is different from a digit.

In general, I record my cassettes without the use of noise reduction systems. On cassettes of the first type, this leads to a well-heard hiss, which is not as bad as you might think. And on cassettes of the second type, the level of self-noise is low enough to not bother with all kinds of Dolby. Oh yeah, Dolby HX Pro is still prevalent on high-quality technology, but it has nothing to do with noise reduction. This is a dynamic change system already familiar to us from the previous balalaika of bias current. By varying the bias power depending on the loudness of the sound signal, it allows to improve the output at mid frequencies. So it goes.

As you can see, the set of problems in user devices thirty years ago is very different from the current ones. Engineers and developers, however, still have tasks with similar properties: how to assemble a

Perhaps the best implementation of the format of a compact cassette was in devices for playing the next format - Digital Compact Cassette , developed in the nineties by Philips. The DCC was a slightly modified cassette with digital data written on 9 parallel tracks (about 250 megabytes on both sides). Chip format was compatible with conventional cassettes, but only for playback. And now, they say, these devices reproduced even ordinary cassettes very well, since the requirements for a mechanism for playing digital data were obviously higher. The project was a failure. Modern tape drives their pedigree are more likely from video recorders, and have little in common with tape technology.

My experience of “late” acquaintance with audio cassettes shows: nothing lasts forever. The technology landscape we are used to can change completely in 10-20 years. And even though I appreciate the technology of technology, for nostalgic, financial and other reasons, I am not against this inevitable evolution. After all, to send a "smartphone" or "laptop" or "tablet" to the dustbin of history, you need to come up with something new. I wonder what that could be.