"Red is steeper than blue": color hierarchy in different cultures

- Transfer

In 1969, two researchers from Berkeley, Paul Kay and Brent Berlin, published a book about a rather innovative idea: each culture in history, developing its own language, came up with names for flowers in the same order.

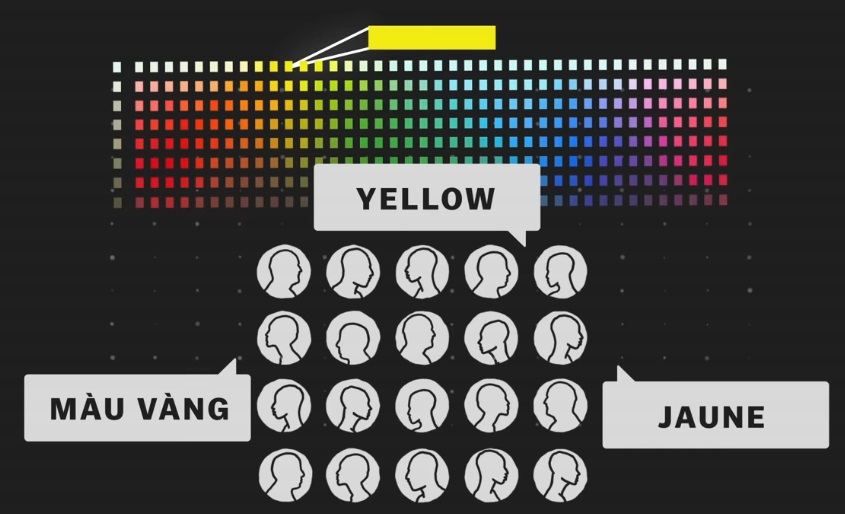

They figured it out on the basis of a simple color identification test, in which 20 respondents distributed 330 color cards by name.

If a language had six words, it was always black, white, red, green, yellow and blue. If four, it was always black, white, red, and then green or yellow. If there were only three, then it was always black, white and red, and so on.

The theory was revolutionary - and it shaped our understanding of how color terms appear.

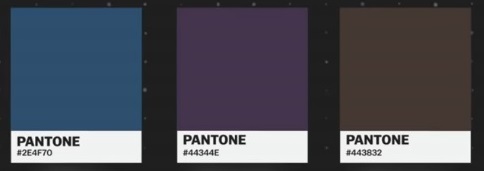

If I showed you these samples and asked for the colors, what would you say?

The translation was made with the support of the EDISON Software company, which is professionally engaged in web development and recently redesigned its website .

You would probably say that it is blue, purple and brown.

But if your native language is Wobé from Côte d'Ivoire, then you probably use one word to denote all three colors.

This is because not all languages have the same number of basic color categories.

In English there are 11. In Russian 12.

And in some languages like Wobé only 3.

Researchers have found that if a language has only 3 or 4 primary colors, they can usually predict what colors they will be. So how do they do it? As one would expect, in different languages different words are used to designate colors.

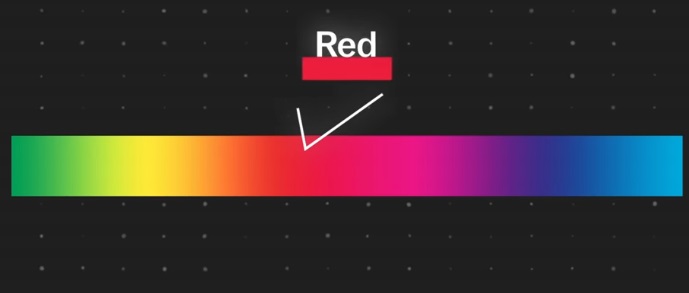

But researchers were not interested in these simple translations, but how colors in principle receive names. Because despite the fact that we are accustomed to thinking about colors in categories, in fact, color is a spectrum.

It is completely incomprehensible why we should have a base color term for this color:

but not for this:

Until 1960, it was widely believed among anthropologists that people simply chose colors from the spectrum randomly.

But in 1969, two researchers from Berkeley, Paul Kay and Brent Berlin published a book to refute this assumption.

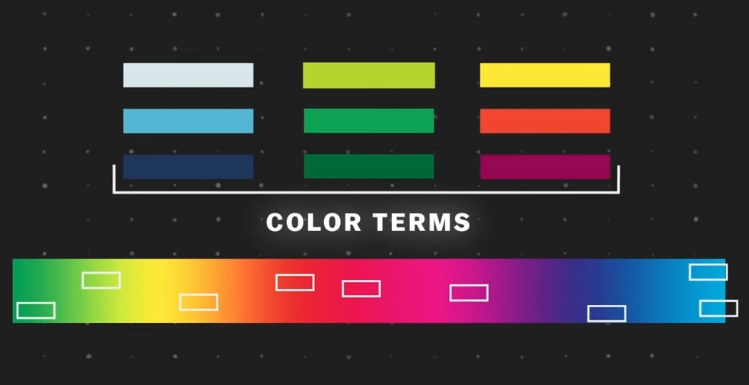

They asked 20 people who spoke different languages to look at these 330 color swatches and classify each of them according to their primary colors.

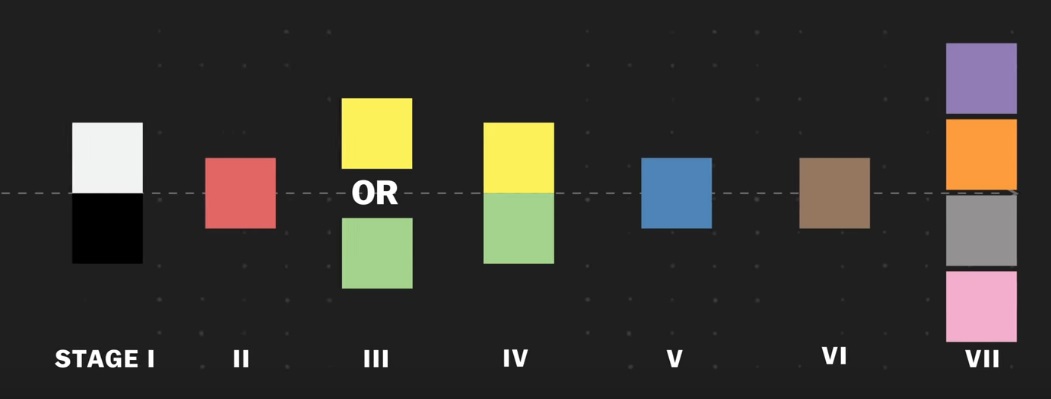

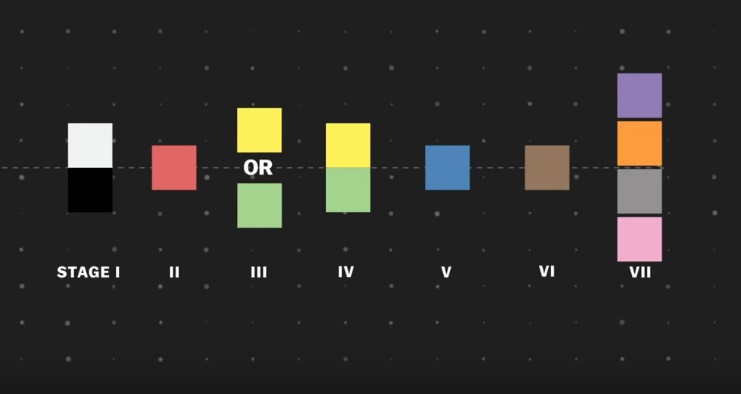

And they found something similar to the universal picture: if the language had six basic words for color, they were always for black (or dark), white (or

light), red, green, yellow, and blue.

If they had four primary colors, they were black, white, red, and then green or yellow.

If only three , then black, white and red.

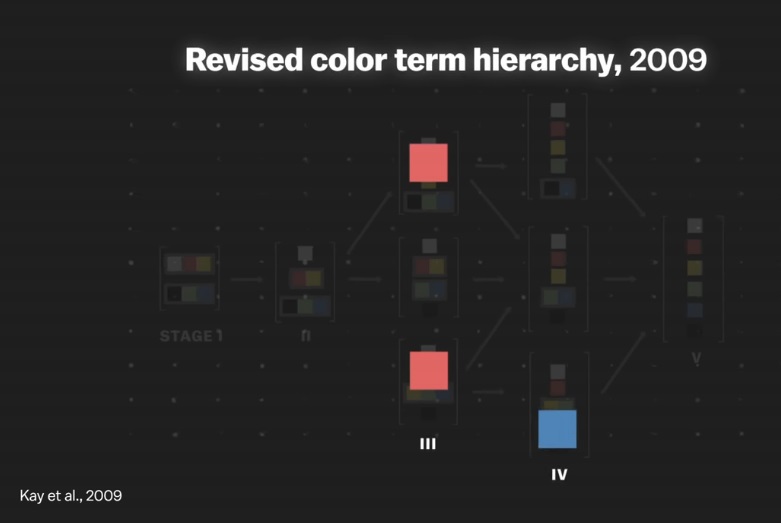

It has been suggested that as languages develop, people create color names in a specific order.

First black and white, then red, then green and yellow, then blue, then other colors like brown, violet, pink, orange and gray.

This theory was revolutionary. They were not the first researchers interested in how we call colors.

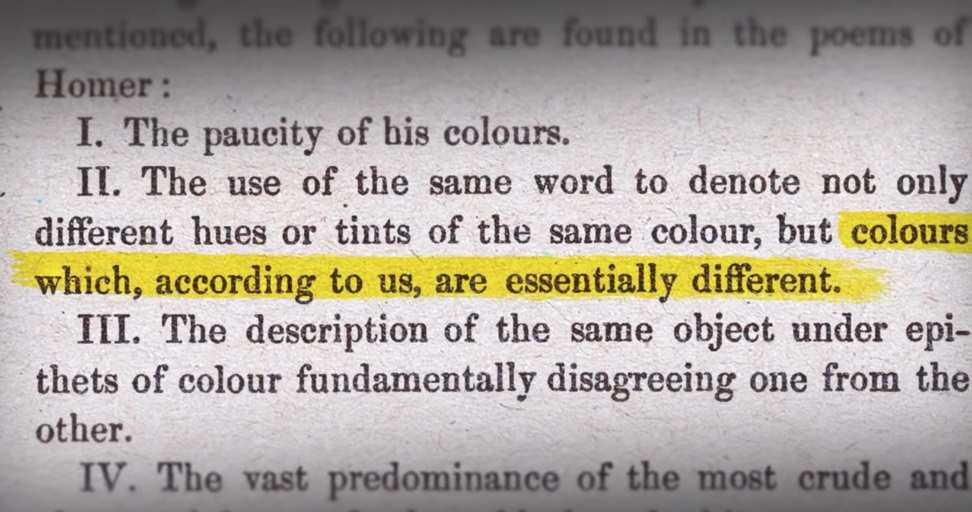

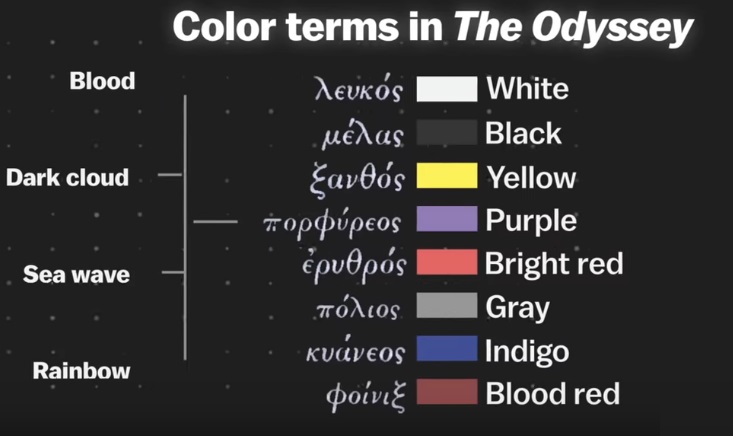

In 1858, William Gladstone, who later became Prime Minister of Great Britain for four years, published a book about Homer's ancient Greek work.

He was struck by the fact that throughout the text there were not many colors, and when they were mentioned, Homer used the same word for “colors that, in our opinion, are significantly different.”

He used the same word for violet when describing blood, a dark cloud, a wave and a rainbow and spoke of the sea as something resembling wine.

Gladstone did not find any mention of blue and orange at all.

Some researchers took this book and other ancient writings as a pretext for the erroneous assumption that before society was color blind .

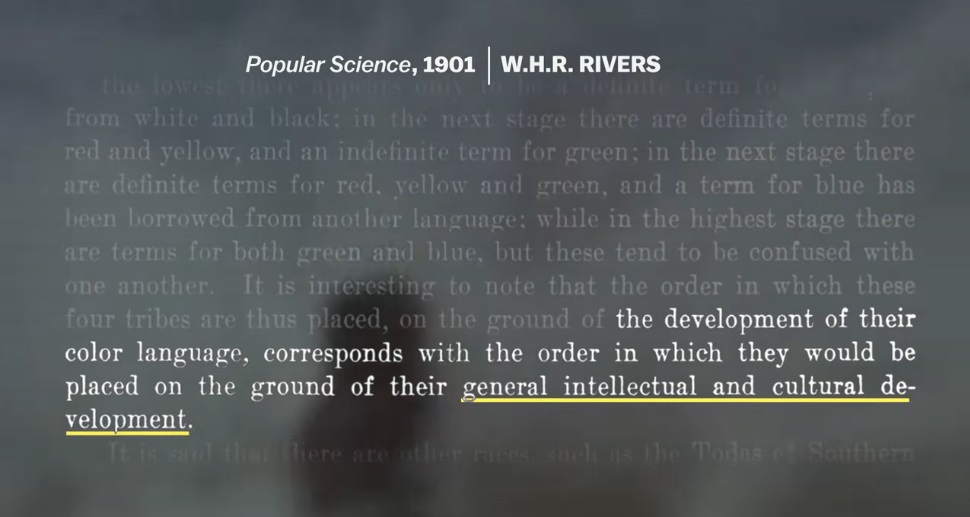

Later in the 19th century, anthropologist William Rivers went on an expedition to Papua New Guinea, where he found that some tribes had only words for red, white and black, while other tribes had additional words for blue and green.

“The expedition was to research crops on a remote group of islands in the Torres Strait between Australia and New Guinea. Her goal was to explore the mental characteristics of the islanders. ”He argued that the number of color terms in a population were related to their“ intellectual cultural development. ”

And used his conclusions to assert that the Papuans were less physically developed than the Europeans. Berlin and Kay did not make such racist conclusions, but their color hierarchy was faced with a huge amount of criticism.

First, critics noted that the study used a small sample size of 20 people, all of whom were bilingual English-speaking people, and not native speakers. And almost all languages were from industrialized societies - this is hardly the best portrait of the whole world.

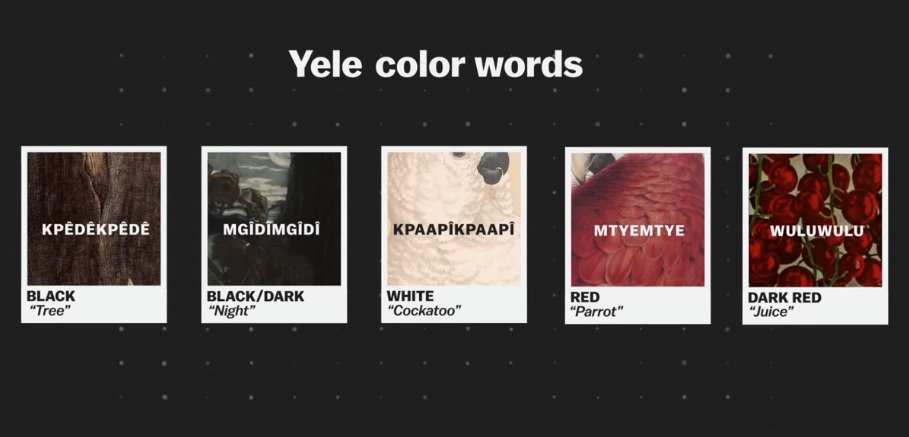

But this is also related to the definition of what the “primary color term” is. In Yele in Papua New Guinea, for example, there are only basic color for black, white, and red.

But there is a wide lexicon of everyday life. Objects such as sky, ash, and tree sap are used as a color comparison and cover almost all English words for color.

There are also languages such as Hanunó'o in the Philippines, where the word can mean both color and physical feeling. They have four basic concepts for describing color - but they are on the spectrum of light against darkness, strength against weakness and moisture against dryness.

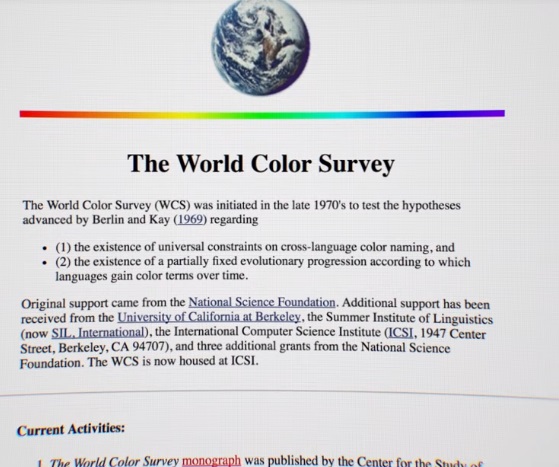

Such languages are not suitable for the color identification test. But by the end of the 1970s, Berlin and Kay found the answer for the critics. They called it World Color Research .

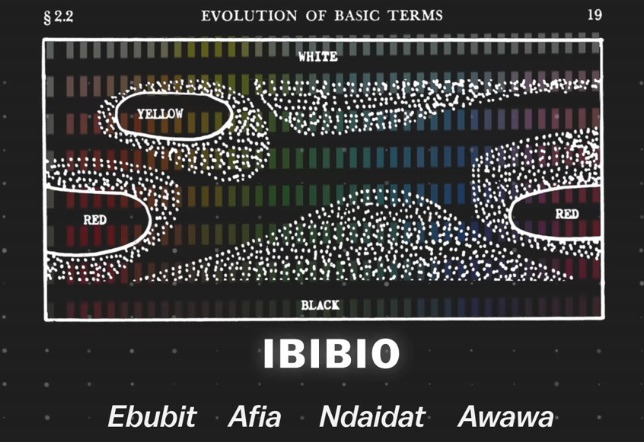

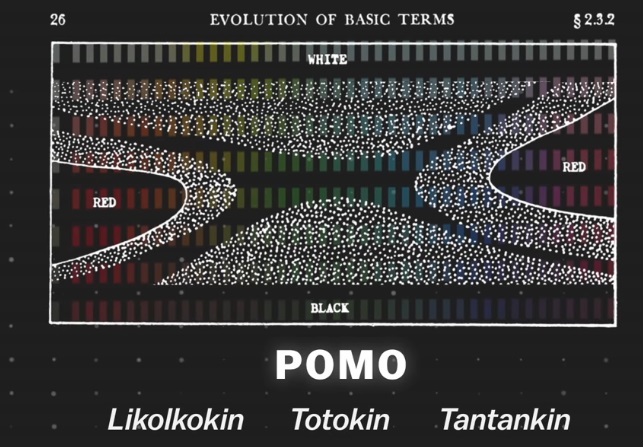

They conducted the same test for 2,600 speakers of 110 languages from non-industrialized societies, which were not previously taken into account. They found that with some corrections, the color hierarchy is still valid.

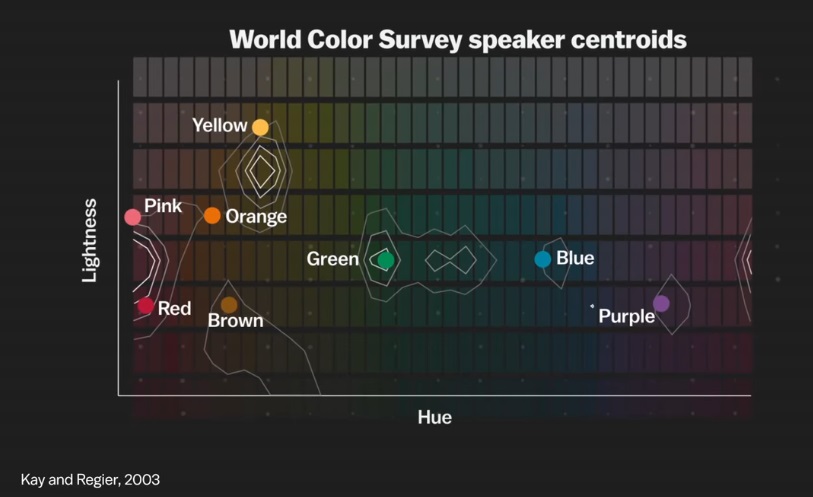

Eighty-three percent of languages correspond to a hierarchy. And when they averaged the central point, where each speaker identified each of the colors of their language, they ended up with a kind of heat map.

These results were very close to the average responses of English-speaking people, which are indicated here.

This is what Paul Kay says:

“It just happens that most languages make abbreviations in the same place. Some languages have fewer abbreviations than others. ”

(this is about the decision of the peoples to “throw out” any color from the vocabulary)

Thus, these color stages are widespread throughout the world ... but why?

Why is the word for red placed before the word for blue? Some have suggested that the stages correspond to the brightness of the color in the natural environment. Red is in the blood and in the mud. Blue, in turn, was met quite rarely before the production of various products.

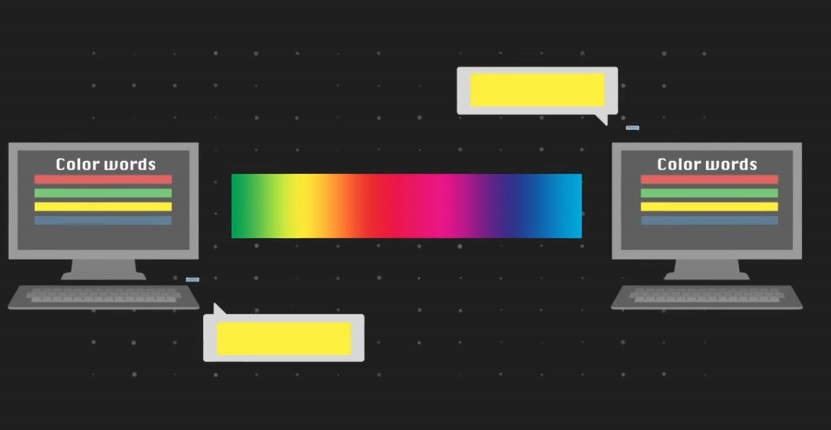

Recently, cognitive science researchers have studied this issue by running a computer simulation of how language develops through conversations between people. The modeling represented artificial “middlemen” with several colors at a time, and through a series of simple negotiations, these “middlemen” developed common notation for different colors.

In what order did these designations appear? First, the reddish tones, then green and yellow, then blue, then orange.

The result is very much the same as the original. And this suggests that there is something in the colors themselves that lead to this hierarchy.

Red is fundamentally more distinct than other colors. So what does all this mean? Why does it matter?

Well, it tells us that, despite our many differences between cultures and societies ... there is something universal about how people try to understand the world.

Still

More about the studies mentioned in this video:

- Cook, Kay and Regier on the Poll on Flowers

- Stephen C. Levinson on color terms Yele

- John A. Lucy on color terms Hanunó'o

- Loreto, Mukherjee and Tria on Flower Naming Simulations

To learn more about how words for the colors of your language can affect your mind, check out this video lecture: